Patterned tentacles burst from the wall of Louisville’s 21c Museum. They are suspended in motion, paused in the act of wriggling free from the gallery’s white wall. Viewed at a distance, Frances Goodman’s Medusa (2013-2014) appears wet. Each tentacle seems coated by a glossy residue, projecting a luminous sheen. A few steps closer and scales begin to take shape—the tentacles’ patterns have been meticulously constructed from thousands of acrylic fingernails.

Goodman recodes these mass-produced ornaments, turning a beauty industry commodity against itself. The decorative becomes subversive—often overlooked as a mere form of bodily artifice, these acrylic prosthetics have been tightly assembled to encase phallic wall protrusions. Medusa is a three-dimensional creature that stretches its mythological ties to masculine aggression and feminine seduction, yet also mines the meaning of an object that—through fashion advertising—has come to signify femininity.

In their 1973 article in Womanspace Journal, Judy Chicago and Miriam Shapiro asked: “What does it feel like to be a woman?â€[1] 21c Louisville’s current exhibition, The Future is Female, takes inspiration from this legacy of feminist writers, artists, and activists of the 1970s, exploring the varying trajectories of craft-based practices, mythology, ecology, and identity. What resonates most, however, is the exhibition’s timing. In the United States, the resistance to women’s rights has encountered a social and political acceptability unseen since the years of the Reagan administration.[2]

What does the phrase “The Future is Female†mean in the age of Trump? 21c Louisville’s latest exhibition does not ask this question—at least not explicitly. At a time, however, when the spectacle of reality television has merged with sexism of politics, when misogyny is dismissed as “men being men†(and then rewarded with a presidency), when government funding for the National Endowment for Arts hangs in the balance, when a large majority of politicians view gender as biologically determined and not socially constructed, and when the leader of the so-called free world flirts with a nuclear arms race, futurity—specifically a future that incorporates women and the arts—seems optimistic. Yet this optimism and political energy is partly what fueled the artists of the Women’s Liberation movement in the 1970s.[3]

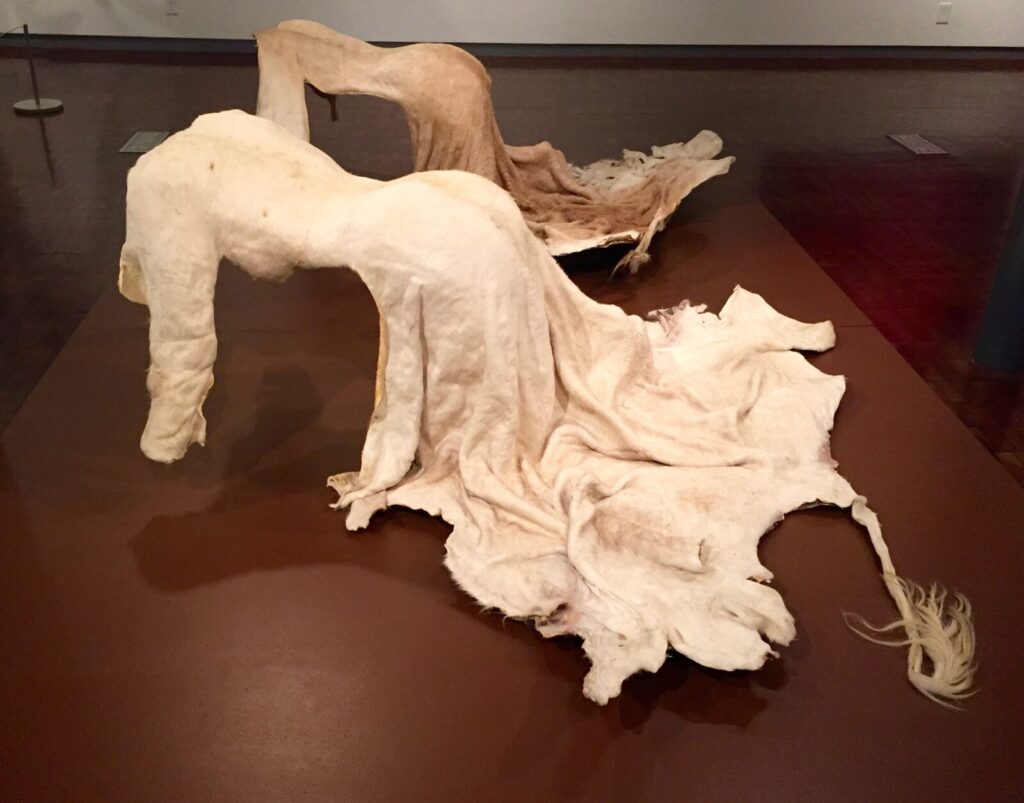

A prominent thread connects many of the works in The Future is Female—mortality is referenced not only through the human body and the abject, but also through a consideration of globalization’s slow decay of both cultures and ecological systems. Nandipha Mntambo blurs the line between skin and clothing by structuring cowhide into rigid human-animal hybrids. Cast from the artist’s body, two ghostly figures rest on their arms and legs—frozen in the act of crawling. As the cowhide slowly melts down the figures’ backs, its stiff ripples condense and begin to resemble folds of human skin. Tails protrude from the gathered hide.

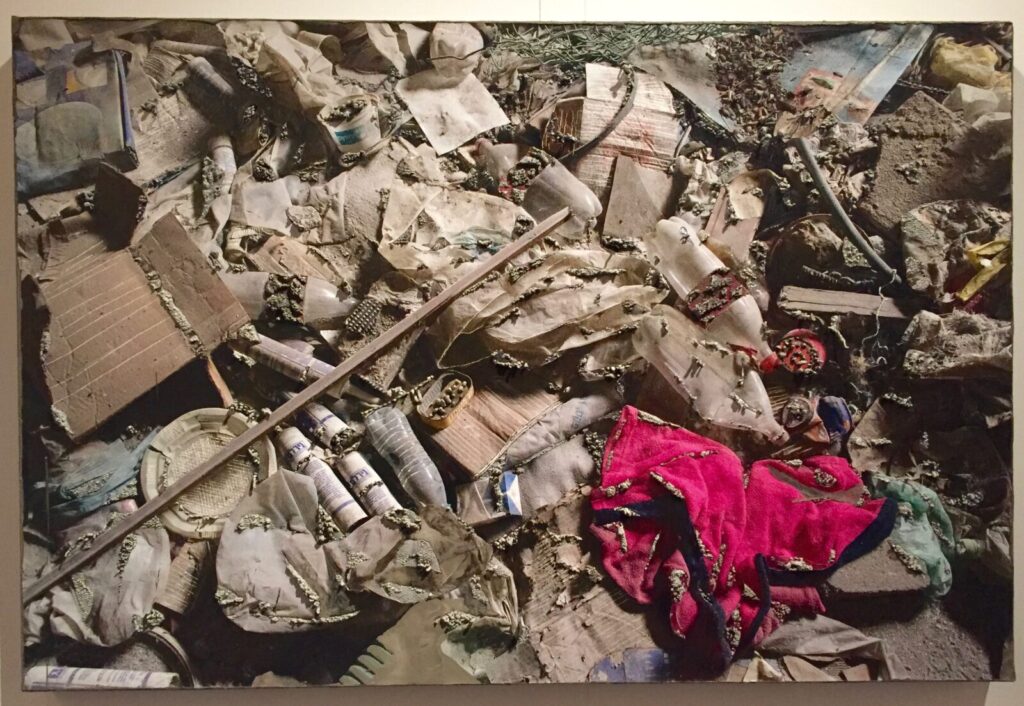

In the mixed-media work of Naomi Safran-Hon, the human body is present through detritus—remnants of clothing intertwine with obliterated concrete, capturing the bulldozed homes of Wadi Salib, a neighborhood once home to Palestinians and Mizrahi Jewish inhabitants before its confiscation by the state of Israel in 1948. Safran-Hon inserts lace and concrete directly into an archival inkjet print, layering a third dimension onto what is normally flattened by camera and printer.

To be clear, the phrase “the future is female†is not a recent addition to feminist discourse. It first appeared on a T-shirt in the 1970s.[4] The original design was made for Labyris Books—the first women’s bookstore in New York City. Liza Cowan photographed her then-girlfriend, Alix Dobkin, wearing the shirt in 1975. Forty years later, in 2015, the image of Dobkin was posted on h_e_r_s_t_o_r_y—an Instagram account that documents “herstoric lesbian imagery.â€

E.V. Day’s striking Waterlily (2011) pulls anatomic imagery from the artwork of her foremothers—Georgia O’Keefe and Chicago. Through enlarging the vivid fuchsia water lily that she collected, pressed, and then digitally scanned during her residency at The Claude Monet Foundation in Giverny, Day reclaims past histories of feminist investigation. The flower’s fleshy texture and prominent reproductive organs are magnified through the scanning process, and its enlarged form is both foreboding and seductive. The print’s pigment is so concentrated that it casts a light pink glow on neighboring works.

On the wall parallel to Medusa, three circular hand mirrors are individually framed by hot-pink resin Venus symbols. The mirrors are lightly etched with a single word in all-capital typeface: FEMINIST, EQUAL, or POWERFUL. Michele Pred’s Reflections (2015), as they are displayed across from the acrylic-nail monster, reexamine the mythological tale of Perseus and Medusa.

When approached at a specific angle, the mirrors can reflect Medusa with the addition of Pred’s positive language—a clever positioning that references Perseus’s use of a mirror to evade Medusa’s fatal stare, but also pushes against stereotypes of women in classical mythology and their prevailing societal effects.

The Future is Female is a careful selection of important works by emerging and established women artists: Jenny Holzer, Monica Cook, Kiki Smith, Sanell Aggenbach, Gaela Erwin, Nina Katchadourian, Carrie Mae Weems, Vibha Galhotra, Alison Saar, Tiffany Carbonneau, Kathleen McQuade Olliges, Hanna Liden, and Julie Levesque. The exhibition includes artists from Africa, Europe, Asia, and North America, but Katchadourian’s homage to David Bowie and Freddie Mercury—Under Pressure (2014)—takes place 35,000 feet above ground.

In an airplane restroom, she “recreates†Mercury and Bowie’s 1981 duet, using a standard polyester airline blanket, toilet paper, and the contents of her carry-on luggage to construct costumes. Under Pressure merges Katchadourian’s humorous performance with a poignant critique, as Mercury and Bowie rejected gender constructs rooted in patriarchal standards. The Future is Female embarks on a similar mission by pushing against the grain of normativity and advocating for a future that surmounts the current sociopolitical climate.

The Future is Female is on view through May 2017.

[1] Whitney Chadwhick, Women, Art, and Society, 5th ed. (New York: Thames and Hudson, 2012), 378.

[2] Chadwhick, Women, Art, and Society, 378.

[3] Linda Nochlin, “’Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?’ Thirty Years After,â€Â Women Artists: The Linda Nochlin Reader, ed. Maura Reilly (New York: Thames and Hudson, 2015), 311.

[4] Marisa Meltzer, “A Feminist T-Shirt Resurfaces from the ‘70s,â€Â The New York Times, November 18, 2015,