The inaugural KMAC Triennial features twenty artists who live or have roots in the state of Kentucky. Selected by jury from a pool of over 200 applicants, the variety of work attests to the vitality of creative practice currently happening in or loosely stemming from the state, but stops short of defining or locating any thematic or conceptual lenses through which to understand the state of contemporary Kentucky art.Â

The show uses the title Crown of Rays, referring to a particular genus of the Goldenrod, the state flower of Kentucky. The gallery text makes allusions to ceremonial headwear and deifying haloes tied to the flower as well as pollination and ecology, using the flower’s botanical and symbolic properties as what curator Joey Yates sees as an elastic concept for grouping such a diverse array of artists and practices. Sadly, an image of the flower appears nowhere in the galleries, either as a visual reference point or botanical metaphor, severing any coalescing work the title could perform and leaving the disparate selection of artworks to each stand on their own with little conceptual or formal connections between them.Â

Fortunately, there are a number of strong pieces in the show, particularly those that engage with the museum’s historical engagement in craft, but with the contemporary art sensibility KMAC currently pursues. Philis Alvic’s handwoven panels evoke windows from all over the world, creating a tension between the accumulation of pattern and fabrics on a rich, tactile surface and the illusionistic picture plane. Hunter Stamps’ ceramic pieces, which hug columns, seep out from walls, sink into the floor, or plop down as undignified specimens on a hospital gurney, similarly make process and craft evident through their surfaces and biomorphic forms, while at the same time viscerally alluding to open wounds and sores on the body.Â

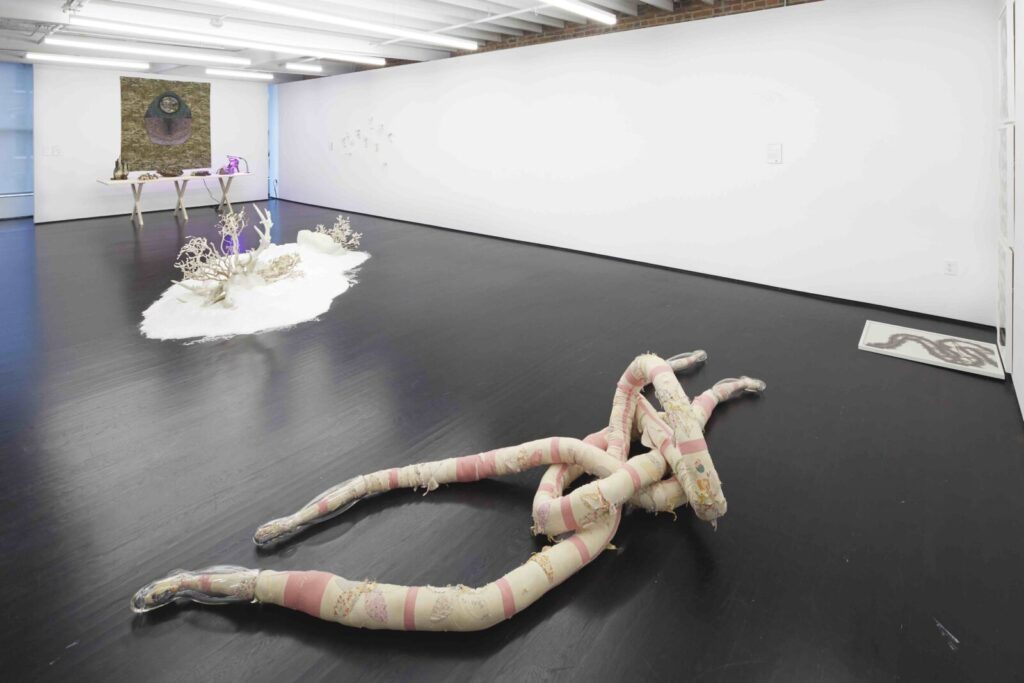

On another floor, different craft traditions coalesce into compelling installations. Rachel Frank’s tabletop display of stoneware, video, and plant assemblages against the backdrop of her hanging fiber and beadwork Pattern for a Yurt III (2016) makes the most explicit reference to Kentucky ecologies in the show (albeit sans Goldenrod) through new and old media. Melissa Vandenberg’s Shed (2019) alludes to the animal world through multiple genealogies of craft, featuring two sets of intertwined, snakelike legs reminiscent of Sarah Lucas’ work. These forms appear to be molting an aging and deteriorating quilt as they sprawl across the second-floor gallery space, capped with boot-shaped glass components completed during the artist’s residency at the Corning Museum of Glass.Â

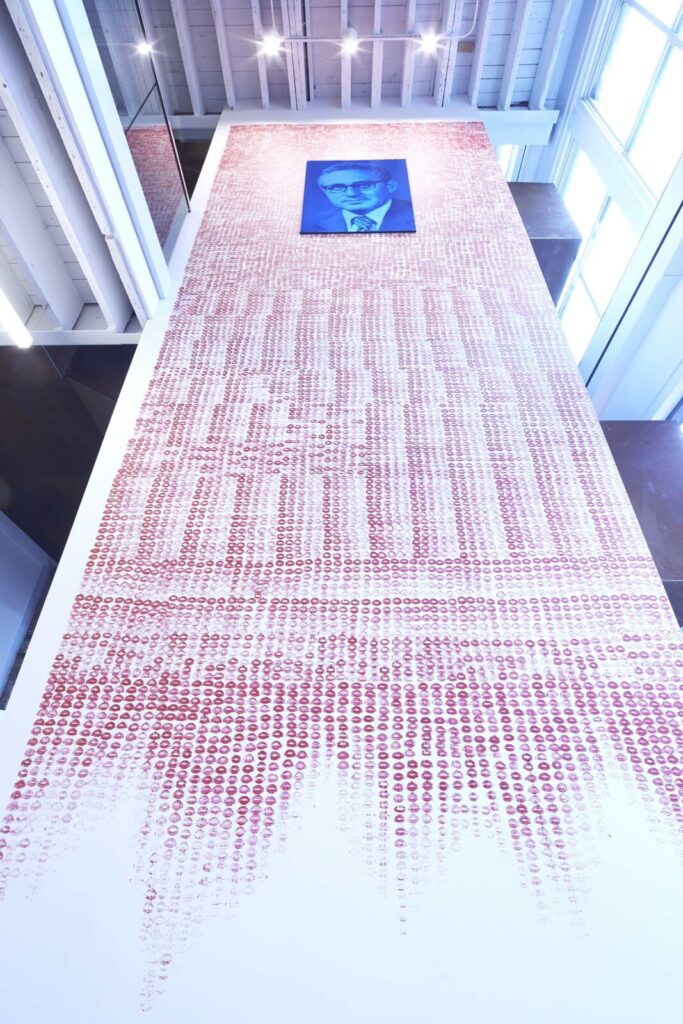

Not wanting to be limited by an at-times parochializing focus on traditional craft forms, the jury chose a selection of artists spanning a number of different media. Two conceptual works that traverse the stairwell of the vertically-oriented museum’s three gallery floors best realize the potential of KMAC’s space, though perhaps at the expense of working formally or conceptually with the other works in the show. Vinhay Keo’s Kissing Kissinger (Portrait of a Nobel Peace Prize Winner) (2019) entails a photographic portrait of Kissinger from 1973 surrounded by a sea of individual red body prints of the artist’s lips. Running down a wall that cuts through the gallery’s main floors and fading just before hitting the floor, the sea of lip stains produce a performative, punning, and queer re-reading of Kissinger’s name while also darkly alluding to the millions of Cambodian lives lost or displaced due to the former Secretary of State’s policies. Complementing Keo’s installation is a site-specific sound piece by Aaron Rosenblum, High, Low, and In Between (2019). Merging pure tones with urban and rural field recordings, these sounds move up and down speakers set throughout the open stairwells and resonate throughout the gallery spaces.Â

The geographic push and pull generated by the two site-specific works in the stairwell carries throughout most of the show, but without much rhyme or reason. On the second floor, dizzyingly complex conceptual black and white photography of the KMAC gallery spaces by Casey James Wilson lies between Sean Satrowitze’s somewhat ideologically muddy installation of a proposed funerary ritual for the decapitation or removal of Confederate monuments in the region and Vian Sora’s Max Ernst-inspired abstract paintings responding to the artist’s traumatic experiences in her native Baghdad. From the hyper-local to the geopolitical, and the coldly conceptual to the intensely internal, these works benefit little from proximity to each other, and possibly need more conceptual room to breathe (particularly Starowitz’s, which would benefit from further research and a socially-engaged public component).

In the following room, Elizabeth Mesa-Gaido’s assemblages and prints juxtapose the playful forms and textures of piñatas with images from revolutionary Cuba and toiletries and essentials commonly unavailable on the island, where her family has roots. Complementing Mesa-Gaido’s meditation on need and abundance through mass-produced commodities are Lori Larusso’s sign-painted still-life installation Pastiche of Good Intentions (2019) and Kristin Richards’s Donald Judd-inspired vats of a rainbow of Dawn dishwashing soap that sit oddly atop a paneled wood staircase, a work that similarly needs some air, possibly as two components in a larger installation.

Next to this gallery are perhaps the show’s two biggest misses: a horizontal installation of Jimmy Angelina’s pop culture-inspired black and white drawings, which work much better in the coloring book form available in the KMAC gift shop, and the only primarily moving image-based work in the show, Sarah Lasley’s Totality (2019), a kitschy panorama of dramatic National Park scenery overlaid with individual karaoke singers belting different songs in street clothes. Lost in the shuffle are Andrew Cozzens’ interactive and conceptual meditation on art consumption and forms of biological and cultural extinction, which is unfortunately tucked away in a rear gallery and was not functioning when I visited, and Harry Sanchez, Jr.’s compelling prints of families torn apart at the U.S.-Mexico border, a work whose urgent tone and direct politics are effective but feel out of place with the other works in the show.

Biennials (and by extension triennials) are tricky, but they have come to dominate the contemporary art world in the past three decades, for better or for worse. Spreading out from former art world centers in order to keep pace with an increasingly globalized world and afford smaller cities—like many in this region—the chance to elevate their artists or local creative economies onto a higher and more visible platform, these recurring exhibitions ideally function as barometers of the contemporary art world. More often than not, however, they merely add to the noise. The KMAC Triennial, with its small size and (somewhat) regional roster, departs from the sprawling city-wide scale and superstar artist list of Front in Cleveland or FotoFocus in Cincinnati, smartly focusing on artists who the curator and jury feel deserve a broader platform. Once raised on this platform, however, the artists seem to be each belting their own tune, echoing the confusing soundscape of Lasley’s video and retreating to the dangerously forgettable form of the open call, juried group show.Â

Lacking a thematic consistency or coherent dialogue among the works, I wonder about the show’s ability to present these artists to new audiences, which, in the end should be the goal of evoking the biennial format. As an inaugural event, the 2019 KMAC Triennial shows great promise in its ability to attract and showcase important work by artists with ties to Kentucky, though those ties are at times weak. With a clearer concept and focus, either through the selection of work or roster of artists, hopefully future versions will advance beyond merely shedding light on important practices in the region. My hope is that future iterations of the triennial will not only showcase artists but ignite important discussions and generate lenses through which to understand their work, or—ideally—prompt us to re-imagine the broader contemporary art landscape entirely.

About the Author: Annie Dell’Aria is Assistant Professor of Art History at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio. Her research concerns the intersection of contemporary art, moving image media, and public space. Her writings have appeared in Afterimage: Journal of Media Arts and Cultural Criticism, International Journal of Performing Arts and Digital Media, Public Art Dialogue, Moving Image Review and Art Journal (MIRAJ), Millennium Film Journal, and other venues. She is currently working on her book, The Moving Image as Public Art: Sidewalk Spectators and City Screens.