Floating approximately halfway between California and Hawaii, spanning more than half a million square miles, is an “island” made up of mostly microscopic plastic. “Island” is in quotes here because the mass is mostly imperceivable to the naked eye and rarely impedes marine traffic but is nevertheless deeply impactful to both human and animal life. The waste that makes up this invisible island, known as the Great Pacific Garbage Patch comes primarily from the populations of three continents (Asia, North America, and South America) and is held in place by what’s known as a gyre, a relatively fixed system of ocean currents that collectively create a vortex of force that is difficult to escape. Across the globe, there are five such gyres. In each one, a similar whirlwind of trash swirls without end.

The phenomenon is relatively new. Most of the garbage patches were first observed in the ’70s and ’80s, about a half century after plastic was originally invented, and have continued to expand since. Although methods are being devised to clear them, little headway has been made to stymie their source: largely single-use consumer plastics and packaging materials, of which somewhere between about 1 and 3 million metric tons enter the ocean each year. The tiny bits of waste are the remnants of our water bottles, plastic bags, and other detritus worn by the sun, wind, and the waves but still permanent and active in our planet’s ecosystem. The bits are found ingested by marine and avian life in increasing concentrations as you move up the food chain. The chemicals that are byproducts of their decomposition affect the makeup of the ocean and its life. The comparatively uncommon but still present large pieces can choke or otherwise constrict body parts of those same animals.

It may be an odd way to consider it, but I think of these massive, dispersed, nearly intangible islands as uniquely contemporary monuments to – and a record of – our way of life. If a population is measured and understood by what it leaves behind and seeks (consciously or not) to make permanent, then this is our Stonehenge, Great Wall, Chichén Itzá, or Great Pyramid. If those places held significance because of their function as sites of ritual or as indicators of state power, then the Great Garbage Patches reveal the altar at which we worship and the offices we are subject to. They are invisible, collectively and unconsciously made, more a stain than a mark, and more permanent than we could hope to be. They are a wonder of the world, maybe a terrible wonder, but a wonder nonetheless.

These hulking and ghostly masses came to mind after a recent conversation with artist, illustrator, and musician Robert Beatty in his apartment and studio, both located in downtown Lexington, about his work across mediums. His apartment, upstairs in a 19th century building near Gratz Park, is a kind of gyre of its own. In his office, books on esoteric practices, ancient archaeology, and electronic music are stacked high on TVs and soundboards. A large computer monitor displays a commercial project he’s working on, surrounded by records, more books, a few coffee cups, and print projects published in the New York Times, the Oxford American, and elsewhere. Robert’s chihuahua, Blue Velvet, rests delicately on a cushion nearby, and follows us into the kitchen for tea.

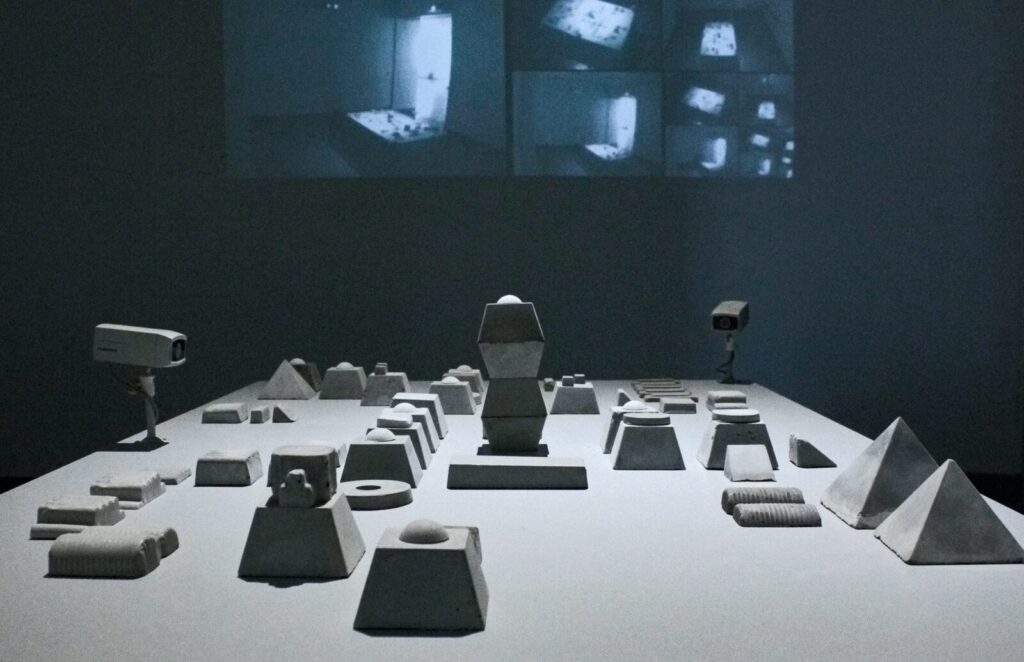

We start our conversation with a discussion of Robert’s most recent exhibition, Place Holder, which remains on view at 21C Lexington through January 2020. The exhibition spans one room on the first floor of the main street hotel, and is comprised of a large central plinth with closed circuit camera footage of the same room projected on the surrounding walls. On the plinth are small cement sculptures arranged in a city-type grid. Some of them are brick-like. Others are more organic. All of them are rendered in a medium, industrial gray. Security cameras surveil the scene from above and feed the footage directly to the walls around them. Although some of the cameras are broadcasting in color, the projections read as nearly monochrome. The small sculptures are reminiscent of architectural models. If rendered to full scale, they might bring to mind the blocky, imposing Brutalist style of the mid-century. Another look and they feel a bit like gravestones. Two of them are pyramids, so perhaps this is the scale model for a mausoleum, or a place for spirits to inhabit after they leave their bodies behind. From above, they seem like the brainchild of a dystopian city planner. The scene is devoid of human life. It could be a ruin or a scene from a future of which we are not a part. When seen through the lens of the security cameras around them, the structures become somewhat uncanny, rendered inhabitable by the confusion of scale until you as a viewer intrude on the frame to provide reference.

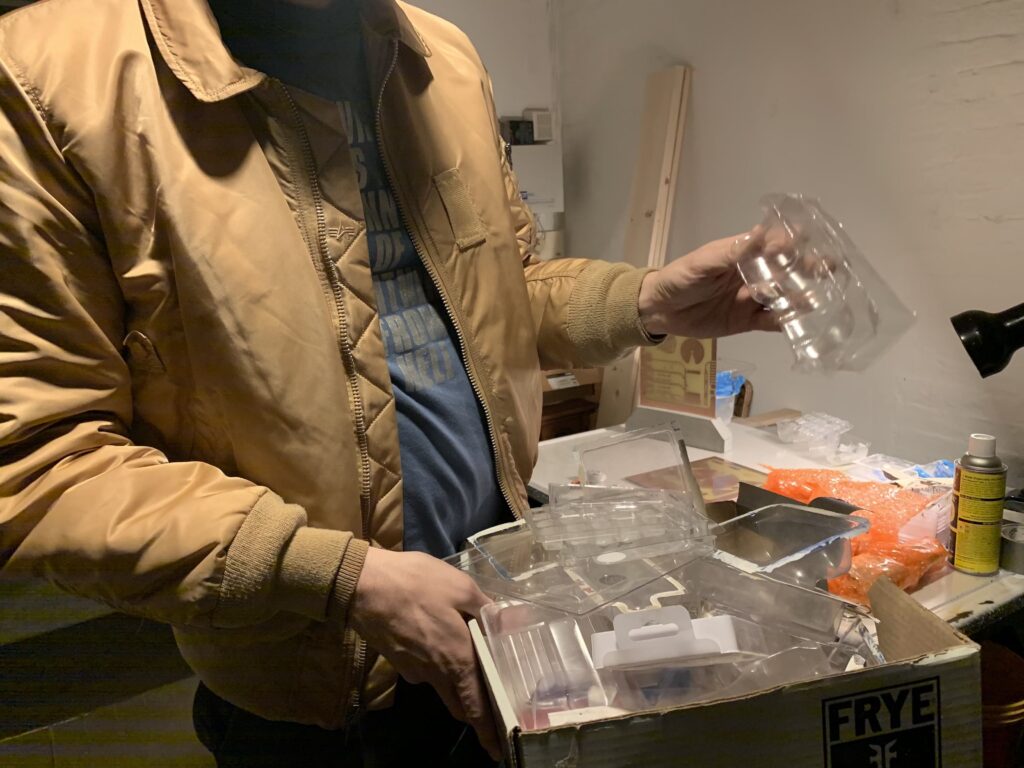

Robert tells me his process for making the sculptures, of which I was totally unaware despite seeing a few iterations of this body of work in the last year, first at the Parachute Factory in an exhibition organized by Alex Brooks, and then at the Atlanta Biennial held at the Atlanta Contemporary curated by Daniel Fuller and Phillip March Jones. The monolithic pyramids, three-dimensional trapezoids, and somewhat colonic tube structures are not, as I thought, cast from artist-made molds, but instead are created from plastic blister packaging. Even if you don’t know what blister packaging is (I didn’t), you’ve certainly dealt with it before. It’s the close-but-not-exact-fitting, often clear, interior packaging element encasing things like batteries, headphones, appliances, speaker cables, toys, and so on. The resulting shapes are remarkably abstracted and unrecognizable, a negative image of the byproducts of our culture’s consumption. Robert notes that what initially drove him towards these forms is their availability. As an artist who works regularly with technology both new and old, he has a lot of gear, and all of it comes wrapped in this stuff. When we move to his studio later in the conversation, he pulls out two large containers brimming with them, big, small, and everywhere in between.

I mention to Robert that I recall seeing he had recently taken trips to the Great Serpent Mound in Adams County, Ohio, and to Stonehenge in Wiltshire, England. Both of these landmarks have potential astronomical and ritual significance and somewhat indeterminate origin stories. It’s not clear how or, ultimately, why they were built. Also up in the air is who is responsible for building them in the first place. Much of Robert’s work, including what’s on view at 21C, is similarly enigmatic and esoteric. He mentions that both places also served as inspiration for that work, and that the forms and their arrangement are meant to mirror archaeological sites somewhat, though the forms are of course derived from contemporary objects.

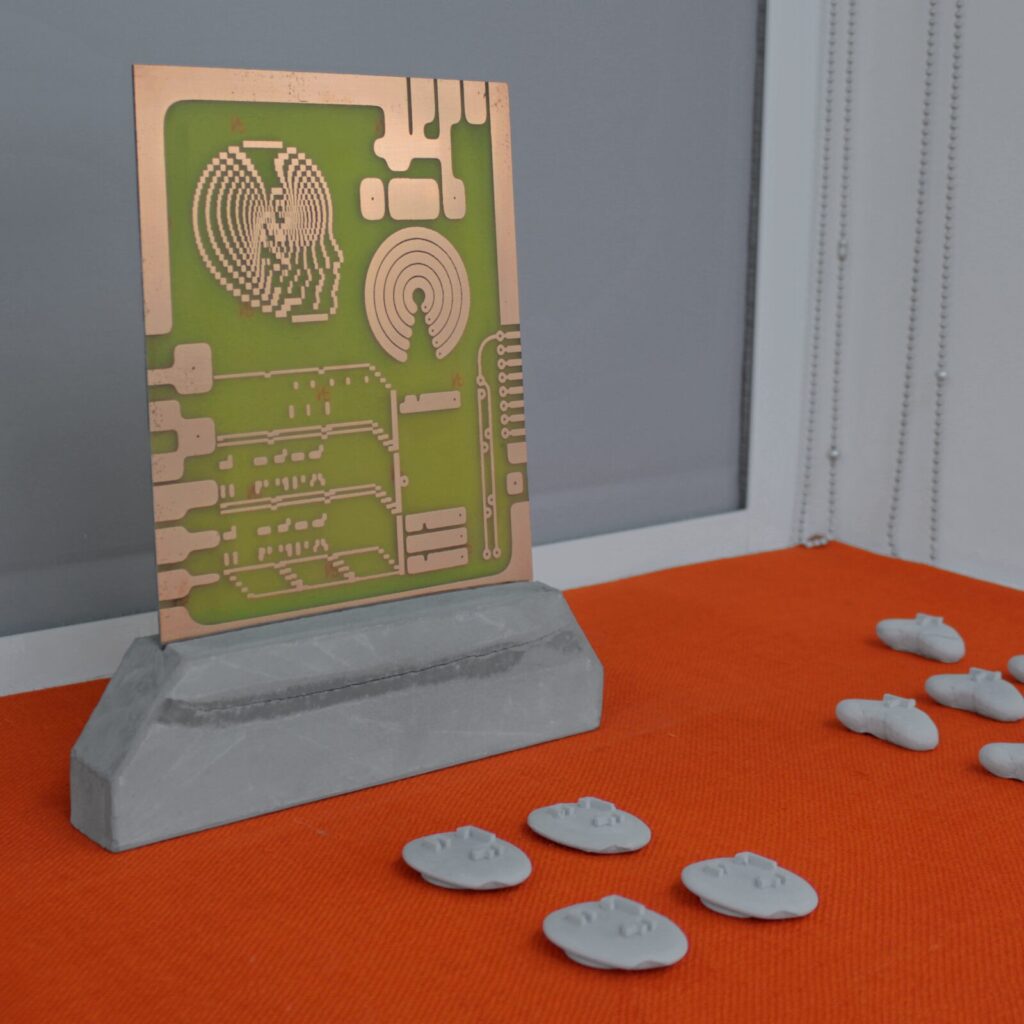

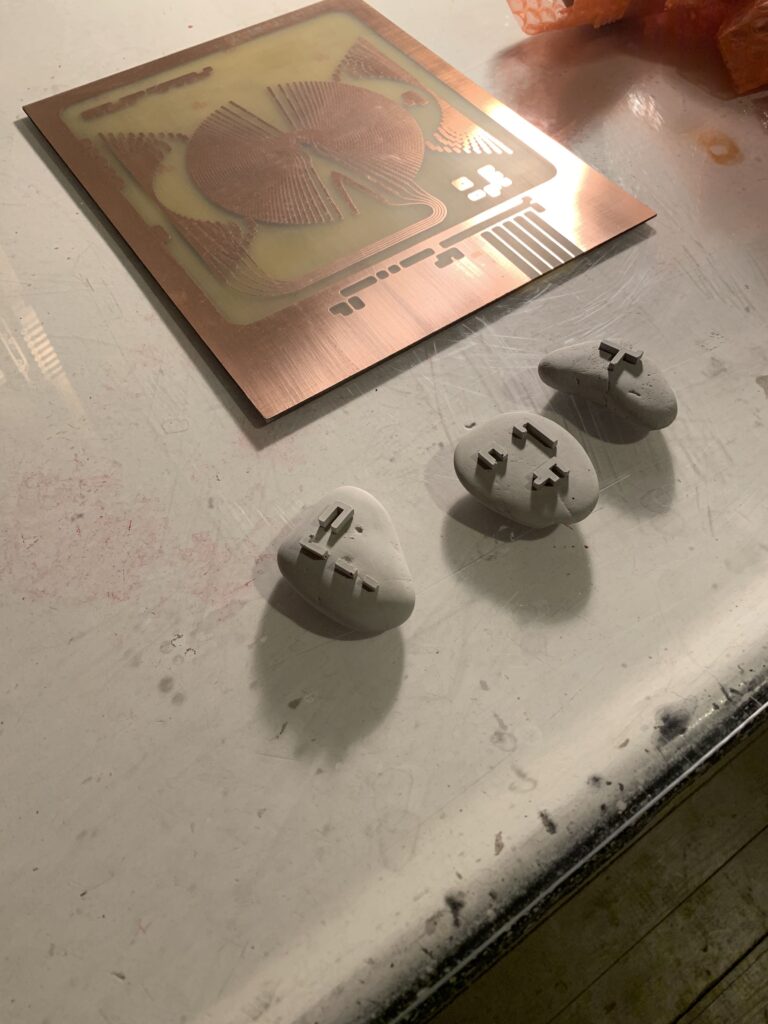

A related body of work displayed at the Atlanta Contemporary is made up of small stone-like objects also cast in concrete. On the surface of the stones in low relief are squared, pixel-like arrangements that are reminiscent of written language but completely illegible. In the exhibition, they were arranged on a bright orange background meant to echo the way artifacts are commonly presented in museums. Similarly suggestive and inscrutable are a pair of flat plates with metallic etching. The language-like elements are replicated, along with linework making them appear as oversized computer chips or, as Robert mentions, Lakhovsky plates used in radionics (a form of alternative therapy that uses electromagnetic waves to diagnose and treat disease). Those plates are just one of a number of pseudoscientific or quasi-spiritual practices that interest Beatty, though not because he believes in them per se. In fact, at one point in the conversation he posits that perhaps he is drawn to the strange and arcane because he feels jealous of the ability that some have to commit so deeply to something so unobservable.

As I get up to leave, we discuss how we think our time might be remembered through an archaeological lens. What judgements would be made about us and what conclusions would be drawn from the things we leave behind?

“And that’s the thing– most of what’s going to be left when we’re not here anymore is going to be plastic. That’s what people are going to find, all this trash. It’s weird that that’s what will outlast us. And that’s part of it, a kind of tongue in cheek thing of taking that stuff and filling it with concrete, giving some weight to it… I really love the way artifacts are shown in a museum. The way that they’re presented. They’re mounted on the wall in these plexiglass cases, this stuff that was probably just trash. But it’s old trash, so it’s… important for some reason?â€