When visiting John Brooks’s studio on Lytle Street, one must pass through several rooms before arriving at the inner sanctum of Brooks’s creative practice. First, one enters the ground floor of the Lytle Street building, an industrial warehouse in the Portland neighborhood of Louisville. Then, up the stairs to the second floor, one finds a cluster of different studio spaces occupied by the loose collective of artists who, like Brooks, occupy Lytle Street, among them Letitia Quesenberry, Chris Radtke, Denise Furnish, Dominic Guarnaschelli, Rosalie Rosenthal, and Jacob Heustis. Through a foyer of second-hand furniture and down the hall, there is a door to the first location of Quappi Projects.

Brooks founded this gallery in 2017 with the aim of furthering the artistic conversation amongst artists and art-lovers in Louisville. Named after the affectionate nickname of painter Max Beckmann’s second wife Quappi (a derivation of Kaulquappe, German for “tadpoleâ€), Quappi Projects hosted numerous exhibitions at Lytle Street before moving during the summer of 2019 to its current space on Market Street. Brooks now operates Quappi Projects out of Market Street and continues his studio practice on Lytle. There, tucked within the bright, white-walled space of the former Quappi Projects, one finds a curtain. And behind that curtain is Brooks’s studio: an enclave for his paintings, collages, easels, and gathered sources of inspiration.

As an artist Brooks is at home with the unknown, the ambiguous, the subtle, and the fleeting. His education had various chapters, from studying politics at the University at Charleston, to studying art at the Central St. Martins College of Art & Design and the Hampstead School of Art while living in London, England. The most lasting conceptual impact, however, came from his time spent visiting Berlin over the years and a summer spent studying under the figurative painter Norbert Bisky in 2015 at Berlin’s AUTOCENTER Summer Academy. Brooks’s admiration for Germanic artistic influences and Germany’s sensitivity to its own dark history finds its way into many aspects of his practice. He often returns to the Max Beckmann quote: “All important things in art have always originated from the deepest feeling about the mystery of Being.†He explains, “I came across that quote some years ago and it stuck with me because that is how I look at the world. We understand a lot, but there is also so much that we don’t understand. Or can’t comprehend…I aim to imbue my work with that sense of unknowing. My creative impulses come from that place, and from a place of longing or missing. There’s a great German word for this feeling: Sehnsucht.â€

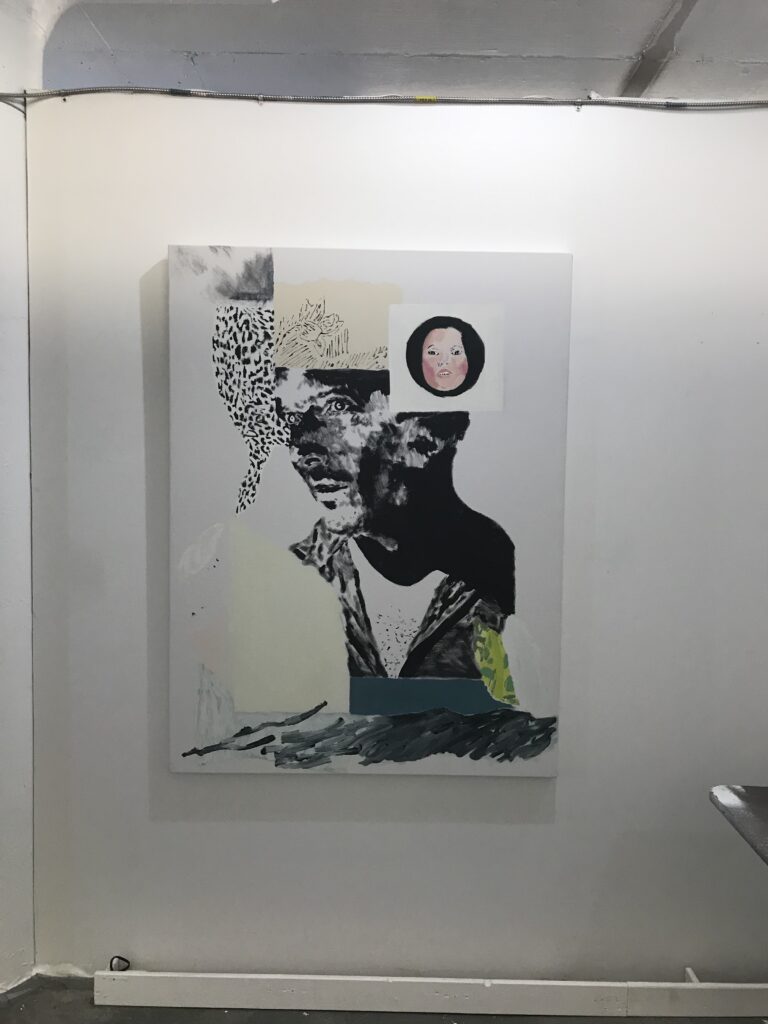

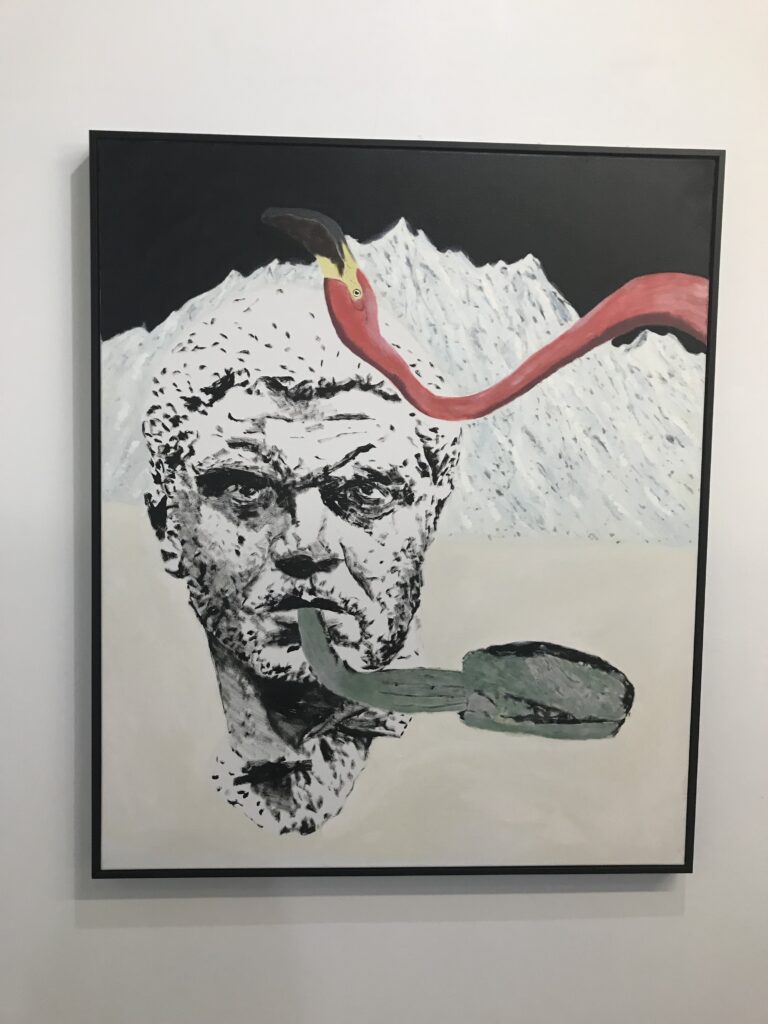

Brooks’s promotion of expansive thinking connects to his work in curation (as the director of Quappi Projects he steers the gallery’s exhibition program), and to his interest in poetry. He describes himself as “a person who writes constantly in my head as I move throughout the day.†Though it felt natural for him to eventually connect his painting to his poetry practice, the result was nonetheless transformative. The titles for his most recent body of paintings are all drawn from his poetry. His series of work, “A Map of Scents,†on view at Moremen Gallery during the summer of 2019, employs this strategy of poetically titling his pictures, as well as a fresh aesthetic that Brooks explains came from integrating his process of collage-making into his painting. Brooks previously felt he could create more freely in the medium of collage, without the historical weight of painting upon him. He had a breakthrough moment when he realized he could combine his collage and painting techniques: “After nearly a decade of almost exclusively creating expressive faces, my painting practice had reached a standstill. I did not see a way forward until it occurred to me to utilize my collages—during the making of which I do not suffer from compositional frustrations—to help facilitate composition in my painting. Through this change in method and approach I feel unbounded.â€

Whereas in recent years a dreamy haziness surrounded Brooks’s figures, in his most recent works he articulates a more defined aesthetic of modeling people in light touches of black paint, with striking clarity in their gazes. These newer figures reside in a world of free-floating images pulled from magazines, websites, social media, and gestural textures of paint.

Collage allows for unexpected juxtapositions. We see this in the layering of eyes, body, faces, and limbs in Brooks’s paintings, as well as distinct swaths of color: a zone of pink, a backdrop of green, an abstracted touch of olive. Collage’s unprescribed form also allows for the use of empty space. Brooks compares the deliberate, blank areas of his canvases to the restraint used in poetry. “Good poetry says the most it can with as few words as necessary,†he reminds us. As readers we must fill in the gaps between words, accordingly there are unpainted areas between the images in Brooks’s paintings. These gaps allow the poetic elements to breathe.

This “push and pull†between the extravagance of oil painting and the discipline of poetry parallels another abiding question in Brooks’s work: how much narrative and explicit (i.e., political) content to include? While the meanings of his paintings might seem open-ended to his viewers, for Brooks the politically motivated inspiration for the work is clear. He cites making works about subjects as diverse as the legacy of World War II (Hürtgen Forest; Berlin is a Dirty Mirror), spousal abuse (Elizabeth in the Same Hour), polyamory (An Abyss of Thighs), and the consequences of queer sexuality in our culture (Constant State of New Sorrows (Orlando Boldewijn)). In the Boldewijn painting, Brooks captures the tragedy surrounding his subject’s death in the penetrating melancholy of Boldewijn’s eyes. Only nineteen years old, the Dutch teenager Boldewijn was found murdered in 2018 following a Grindr date. Violence experienced by young queer men carries a personal significance for Brooks, who lost a friend in 2014 under circumstances to similar to Boldewijn’s (foul play following a Grindr date). Brooks explains that the name “Orlando†also reminds him of the horrific mass shooting in 2016 at the gay nightclub Pulse in Orlando, Florida. While friends and family inspire many of Brooks’s themes, not all the subjects in his painting and poetry are autobiographically inspired. Some works (and texts) speak more generally to the state of our country, society, and the environment, aspiring to the time-honored tradition of the artist articulating universal truths.

Brooks’s calculations in deciding what to reveal and not reveal through the titles and content of his work reminds me of contemporary painter Keltie Ferris’s approach to sharing parts of her queer identity. (Ferris, coincidentally, was also raised in Kentucky.) Regarding her body prints she explained, “There is something about disclosing and not disclosing, or revealing or not revealing: the unfolding…You see everything, but you don’t. That kind of controlled unfurling is queer.â€

Growing up in Frankfort, Kentucky, Brooks describes espousing “a certain timidity as a way to cope and make my way through small town life in Kentucky in the 80s.†As a practicing artist, however, he argues that his work “has never been apologetic.†It’s all there for those who care to probe deeper. He describes wanting to take his stance further, saying, “Moving forward with my practice I plan to continue integrating politics and political ideas and current events into my work, but I want to do it in a way so that the work functions in a variety of ways, that it touches not just on ideas of politics but also ideas of art, too.â€

Paul Valéry once described poetry as a “language within a language.†Poets nestle ideas into words in ways that defy literal and succinct description. Continuing with my Russian doll theme of rooms within rooms and languages within languages, I’d like to conclude by calling attention to micro-passages of paint that Brooks pointed out to me within his paintings. Within his newest works he inserts shapes and color that are influenced by the painters he admires. “I am thinking about specific artists when I’m pondering colors,†he explains. “Max Beckmann and Marlene Dumas with black, Cy Twombly and Ferdinand Hodler with white, Kirchner with purple and green (and Hockney) and Peter Doig, Matisse and Guston with pinks.†Floating within the paintings Bisky Says Joy Comes from the Action and The Collectors are small, variegated strokes of color comprising green leaves, crafted in the style of David Hockney. It’s a quiet, knowing gesture, an intimacy born of looking and (as Bisky says) joy.

The following three poems by John Brooks are published here for the first time, on UnderMain:

November

Morning is ministry,

birdsong homiletic.

Finespun bruise

of autumn on this

newest day. You slip

into a susurrus

of fog, become

indigenous, mute

to the now.

Leaves are lime

of Osage orange,

drop without

gasping. In rain

this slope is slick,

full of snakes aching

not to be seen

scraping in the dregs

of summer’s last

honey. Heron, Snowy

egret, Sandhill crane

forage and hover

as a trio in a shy

pond. Departing geese

are a cadent scene

in four acts. You exult

in the urgent quality

of this dying light.

Tomorrow is already

another goodbye, almost

the deep black lake

of November when

winds get wild,

hailstones cover

the road, and dark

is a song stuck

in your head

or the mood

as you head

to the polls.

Alarm

Wojnarowicz said

what’s happening

now is cause for

alarm. And that

was then. We

are even more

entrenched

in our comfort

now. You know

where I live out

in the middle

of nowhere

all sunsets look

like bad paintings.

My kids think

I’m pretty

at least. I float

on blue song.

Joni resisted

guile, gave into

vivid Ellingtonia.

She was nocturnal;

for me morning

is always a hymnal

but by midday

I remember

who we are. Empires

collapse out of fear.

It’s uniform in a Kubrick,

it’s uniform in a Hitchcock.

I can’t get the monarch

to agree; he’s after

milkweed, goldenrod;

a guest in my garden

or is it the other

way around?

Who belongs

and who leaves

and who remains.

Even friendships

sour into

oblivion

so of course

a culture does.

This is kind of

an old story

but we thought

ourselves immune.

Our coal trucks, our

cobalt plunderings;

we have cornered

ourselves into erasure.

Rockets red glare

in an elephant eye.

Rain hopes to be oil,

oil hopes to be oilier.

I don’t think

the future will be

careful with us.

The present, obviously

not. Today we are

weeping; tomorrow

we are empty.

Where I live

a monarch is a

summer thing.

To summer is

a moonview

of twilight.

David said

keep close

to dark so

it can’t

surprise or

he might

have if he

had lived.

Elizabeth in the Same Hour

In a forest daylight is

melodrama, distance

a drawback. Here is this

photograph of Elizabeth

in the same hour, head

encircled by hair as

black as wood char.

She called herself

an Indian, hesitated

to marry. Marriages

are the regrets

of spooky girls.

What tribe had

she wed? Bill

spoke to horses,

came on foot

from Missouri, drank

too much, went blind

from bile. She learned

how good touch

and bad touch

were parallel

but never touched.

Her children seized

the river in her

and gave it one

noiseless dress.

She kept it spotless,

whether in town

or picnicking.

For generations,

her women had known

how to silo scars

and trespasses;

they understood

just how to manage

difficulties. Disappointments

were chiseled into and out

of their lore. Her own

mother liked to say

she looked beyond

weather to commune

with a musical future.

After Bill, she could see

in total darkness

while carrying only

a vacant lantern.

All Photo Credits: Miranda Lash