Sunspike, Anne Peabody’s current show at the Moremen Gallery in Louisville, Kentucky, opened on March 20; it is available to view online at moremengallery.com. Some works will remain at the gallery until reopening. The exhibition includes 19 works in glass ranging from 8′ by 6′ to only 3″ in diameter. In addition, there is one installation in copper and three paintings on silk. Peabody uses glass for its transparency – she draws behind the clear sheets – and for its reflectivity. Incorporating the viewer’s reflected image is core to her work, as is the veiling that comes from surface glare.

Peabody’s technique is her own variant of reverse foil painting (verre églomisé), a practice glass historians have traced back to the 13th century. These are deeply layered works that repay prolonged contemplation.

Most of Peabody’s paintings on glass depict plant life: hardwood trees, dense underbrush, wetlands and scrub lands well off the tourists’ beaten path. Peabody honors disappearing wetlands by painting with precious metals – silver, gold and platinum. She uses oxidation as an artistic process and as a metaphor for aging and deterioration, of both the environment and the viewer. But she does so with deftness that belies its crusading message and suggests instead a mythic land that straddles the historic and the contemporary.

Peabody is an admirer of fellow Kentuckians: agrarian author and farmer Wendell Berry and the painter-environmentalist-journal-keeper Harlan Hubbard (1900-1988). Like them, Peabody is a localist, and the landscapes she chooses to depict are ones she knows very well, near her current home in Brooklyn, in Kentucky and Tennessee, and close to the home of family in South Carolina. Meditative and rich in surface incident, the work from 2017 to the present interrogates with ever more specificity, interaction and commonality with nature. Peabody wrests aside the common landscape-viewing tropes of awe, timelessness, and passive enjoyment, instead inserting the viewer into her passages. She weaves past into present, drawing on both personal experience and collective cultural memory with an insistence that engages her audience at multiple levels.

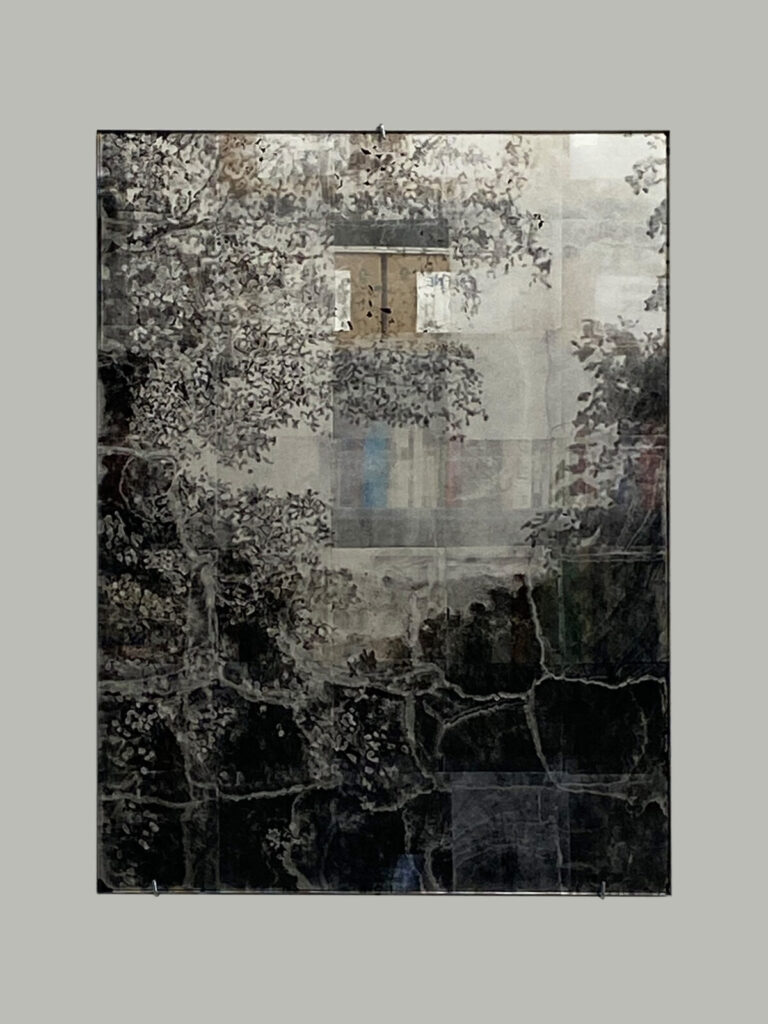

The earliest work in the show is the title piece of the exhibition, Sunspike, from 2017. The 8′ x 6′ composition is composed of 16 plates of glass, each backed with 24 sheets of aged silver leaf. The repeated grids suggest a minimalist order, but depending on the viewer’s angle of vision and the light levels, the grids dissolve in the luminous sheen of the glass and silver. In fact, no view is complete; shifting one’s viewpoint from side to side is necessary to take in the work in its entirety. The image emerges uncannily, as if summoned up from the subconscious. Despite the grids, Peabody’s sensibility is distinctly anti-minimalist and relies on strategies for disorder and distancing of the artist’s hand through chance, delegation, and deteriorated materials. Â

Peabody uses several techniques to lead the viewer to excavate the past. Her monochromatic compositions evoke glass-encased daguerreotypes, the glass plates in the mid-19th century collodion wet plate process, as well as 20th century black and white photography negatives. The sense of seeing into cultural remembrance is reinforced by the composition of Sunspike and other works in the exhibition. They emulate, with more humble subjects, the Romantic Era compositions of the Barbizon and Hudson River schools – stands of arching trees flank a view into the distance and several scenes depict a clearing in the woods or water features. (The artist gave her husband museum postcards and asked him to snap pictures of similar compositions in nature.) The appearance of silver leaf and the silver halide of black and white photography are comparable, so the boundaries between painting and photography, past and present, are repeatedly blurred.

The artist’s technique itself inserts aging into the process. She employs very old, deteriorated silver leaf and there is a high degree of probability that the leaf will fragment before being glued to the glass. Imperfections in the adherence of metal to the glass become accidental details of the landscape. Peabody draws from the back into whatever silver leaf adhered. She uses her fingers or natural bristle brushes. Oil in her fingers or the brushes causes a chemical reaction and breaks down the silver until it falls off like dust, leaving the marks of the artist’s hand in the darker, drawn upon areas. Employing chance again, Peabody leaves the drawing exposed to the air (pollution is a chemical reagent) for a period of time determined by rolling dice, two to twelve days. Japan paint or felt is then applied to the back to halt the process. The drawings that have been exposed for too brief or too long a period are discarded. Â

Peabody has stated that she was inspired by Andy Warhol’s Piss paintings, done in 1961 and 1976-1978: Â

Warhol made meditative yet beautifully complex abstract works of art by urinating on canvas just after it was painted with a combination of copper powder and acrylic medium, then letting the oxidative process do the work. Warhol stated that he made his Piss paintings in order to “sense time as it happens.†Aesthetic form was achieved by the use of bodily fluid that was considered waste. Putting oxidation paintings between the discourses dealing with artistic experimentation with body, abstract art and, finally, eroticism, Warhol invited friends and assistants to pee on the canvases when he realized that the colors of the metals could be changed according to the body chemistry of each individual. Ronny Cutrone, one of his assistants, was said to be among the artist’s favorites, because “…he takes a lot of Vitamin B, so the canvas turns a really pretty color when it’s his piss.â€

After an immersion into a fictional narrative, we are brought back to the moment, present in our own reflection. No longer detached, we are thrown back upon ourselves and, by implication, subject to the same processes of oxidation (the free radicals in the body that are a cause of cancer are also oxidizing agents). It is doubly pertinent that Peabody often selects wetlands for her subjects:Â in these marshy bogs and mires the decomposition of plant and animal life also causes oxidation, enabling the wetlands to store carbon dioxide and methane. Both in imagery and in her process, the passage of time is evoked.Â

Equally striking is Peabody’s draftsmanship: gestural and richly inflected, it is decidedly not a 19th century graphic language. Tennessee Woods from 2020 is based on drawings taken from a photograph of a park that subsequently was damaged by a forest fire. The artist constantly modifies her fracture from sharp linear delineation of foliage to broad, painterly swatches of shade. Appearing and disappearing saplings, stout tree trunks, branches, twigs and underbrush are sometimes depicted boldly, but more often with delicacy, forbearance, and restraint.Â

The draftsmanship is discursive rather than precise, marked by haloes and rifts caused by the condition of the silver leaf. Applications of gold sparkle spray paint emphasize the materiality of the darker area rather than their descriptive function. Seen in isolation, the marks may read as graffiti, calligraphy, or post-impressionist daubs. Peabody provides an invitation to viewing conditioned on the viewer’s commitment to see past the glare of the glass.

Ohio River Clearing through a Square depicts a foreground of rushes and stemmed plants, with overhanging branches defining a rectilinear view of the distant river (the most polluted waterway in the United States). There is an extraordinary richness of blacks, reminiscent of sugar lift aquatint, in the clumpy, blocky shapes at the base of the composition. The distressed silver leaf is an ideal medium for a balance of opacity and transparency. Peabody responds to random threats to wetlands and rivers – pollution, commercial development, invasive species, climate change, agricultural runoff – with a process that parallels in its use of chance procedures the unpredictable and random hazards afflicting these ecosystems. Notably, forty percent of the world’s species rely on wetlands for their survival.

The fecundity of these threatened landscapes is emphasized in two depictions of a South Carolina swampland. Pines, live oaks, magnolia, palmettos, vines and Spanish moss crowd the water view and challenge the observer’s visual access to a distant objective, just as physical access seems improbable. Traditionally, mirrored surfaces are thresholds to varieties of self-awareness or narcissistic self-deception, vanity, insecure doubt or more plain-spoken self-knowledge. In her mirrored works, Peabody leads her viewers to a deeper apprehension of their embeddedness in the same processes and frailties as in the vegetative world.

The copper installation, Walking Thread, may be a reference to Paul Klee’s invitation “to take a line for a walk.†Copper weeds and vines fill a corner, traverse along a wall and seemingly continue through a glass window into an adjacent room. More storytelling than the glass pieces, Walking Thread continues the environmental theme by copying the common vegetation that grows in sidewalk cracks, on the sides of buildings and in the leftover spaces of urban deterioration: these are wildings, alien intruders in the concrete world.

The playwright Sarah Ruhl has remarked, “Narrative is an accumulation of knowledge about the future. We begin in the present and end in the present and in the middle is an accumulation of future possibilities.†The seemingly random pathways of the plants offer a demonstration of the actions of chance; the “accumulation of future possibilities†plays out differently in each installation of the piece. It seems relevant that in their struggle for survival, common street plants are known to hybridize more frequently than cultivated plants. Uppermost in the corner of the installation is a crocheted spider web with a cast spider, giving the installation a fairy tale character. The artist draws templates from the plants she gathers, and traces the leaves onto sheets of copper, then draws veins on each leaf. After the copper has been cut it is soldered to a copper wire petiole, which in turn is soldered to a copper stem. Peabody was trained in plant morphology at the New York Botanical Garden. The precise and laborious documentation may be said to be a way of honoring these hardy survivors.Â

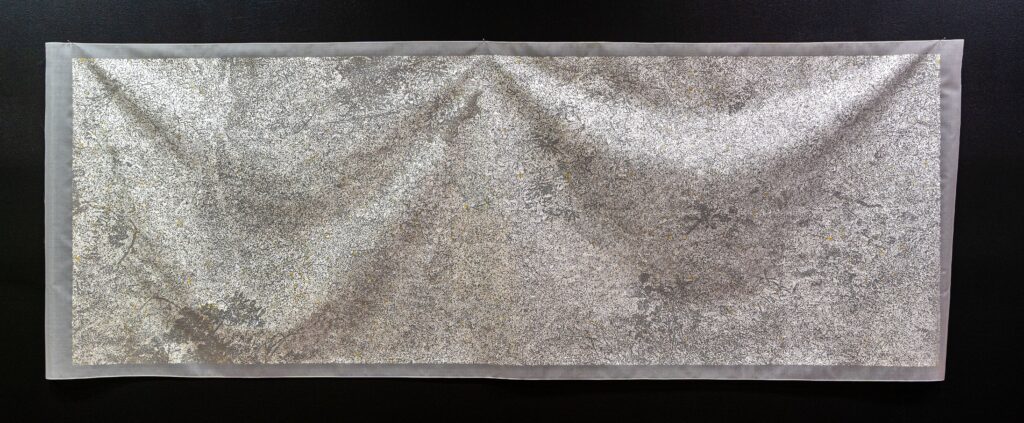

Peabody’s most recent work is painting on Japanese silk. The images derive from a meticulous drawing, blown up until it is pixilated and attached to the silk. Each mark is then drawn on the back of the cloth, in an obsessive process that exhaustively transcribes every twig and leaf. She explains further:

In my newest works, I paint swatches of the Kentucky landscape in small dots and brush strokes, using a combination of acrylic medium, watercolor and gilding size, onto silk traditionally used to make Japanese screen paintings. After the paint and glue mixture cure, I adhere sheets of silver, gold, copper, and platinum leaves to each mark, then brush away the metal that has not stuck. By leaving my paintings unsealed, I allow atmosphere to oxidize each piece.

Moisture, chemicals and other impurities in the air in which they are hung darken and discolor the silver and white gold marks, changing the image and revealing the scenes in greater detail over the passage of time…. The silk is left loose and raw instead of stretched onto the frame, so that each is more fragile and susceptible to the environment.

Despite Peabody’s painstaking exertions, the result on the front is an impression of calligraphic dexterity and spontaneity of touch. An elegant, delicate scintillation plays across the surfaces of the silks, somewhat akin to Mark Tobey’s “white writingâ€, but lighter and more fragile. In density of information they recall the work of Vija Celmins. The pinned cloth is allowed to billow and fold, and the movement of the cloth echoes the quivering light on leafy trees on a breezy day.

The new work bears witness to the artist being on intimate terms with nature, and seems open-ended – fit for all refinements.

Anne Peabody’s art proposes an alternate perception of the natural world. Through reflection, Peabody’s audiences are called upon to see themselves as part of the threatened wetlands, intruding plant life surviving in sidewalk cracks, or evanescent leafy horizons. Her use of oxidation as a metaphor and artistic process brings up a host of current questions concerning personal health and survival (antioxidants, pollution, global warming, environmental degradation), but does so with understated grace. But the question she poses is foreboding: if how we shape the environment in turn shapes us, how are we each to reckon with the impact of dying and disappearing ecosystems?Â