“There are no nouns in the universe,†wrote English critic and poet T. E. Hulme, insisting that in all of existence – everything we know and can possibly imagine – there is nothing fixed, nothing stationary. Any impression of stillness is merely an illusion; instead, all things are in a constant state of flux. Nothing can be pinned down long enough to be defined. FLAW, artist Joan Tanner’s site-specific installation on view at Cincinnati’s Contemporary Arts Center (CAC), aligns with Hulme’s aphorism. Containing no proverbial nouns, the galaxy Tanner presents brims with currents of chance, opportunity, and the palpable energy of the uncertain.

Born in Indianapolis in 1935, Tanner has lived in southern California since the mid-1960s, and has been exhibiting her paintings, drawings, photographs, sculptures, and installations for more than five decades. She works out of two in-home studios – one for drawing and painting, the other for sculpture and fabrication. Within her bifurcated workspaces, Tanner has long explored dualities, contradictions, and the deficiencies that plague our existence. Some of her earliest paintings were diptychs constructed with hinges riveting the two halves, keeping them moored to one another, preventing any cleaving or escape. The daughter of an eye surgeon, Tanner became fixated at a young age with the flaws and imperfections that mar not just the physical body but those in the intangible and the abstract. “Tanner,†writes Curator Julien Robson, “plays with the…precarious in such a manner that form unfolds as a reflection on temporality – of development and decay – in ways that seem purposefully unresolved.†Whether in material or conceptual terms, this festering tension between inevitability, or destiny, and its opposite – infinite possibility – is an alluring hallmark of her work.

Whereas many institutional galleries tend toward a kind of spatial neutrality, the CAC’s rooms do not. This is especially true of the U.S. Bank Gallery which houses FLAW. To fixate on the space is not to disparage it, but rather to recognize and attempt to absorb its complexities. From the perspective of the viewer or considering its architecture, Zaha Hadid’s cosmopolitan building – now nearly twenty years old – shines. From the perspective of an exhibiting artist or curator, the building, with its unexpected dimensions, somewhat aggressively imposes itself, as if it is of the mind that it exists independently from the circumstantial reality of its purpose. Hadid’s design, however, wasn’t born from any disregard for artists, but because she regarded them so highly, being one herself. (It is also a way she can say hello, I’m here in perpetuity). Located on the museum’s second floor, the U.S. Bank Gallery is long, fairly narrow, and populated on one side by three substantial rhomboid concrete supports. Upon – or even before – descending several wide, shallow steps, FLAW begins to come into view. From the outset, it is evident that what you are looking at is an astute response to space rather than simply a selection of individual works that happen to find themselves landed here. If the idiosyncrasies of exhibiting in these spaces can be viewed as a challenge presented to artists by the late architect, it is one that Tanner accepts, embraces, and eclipses.

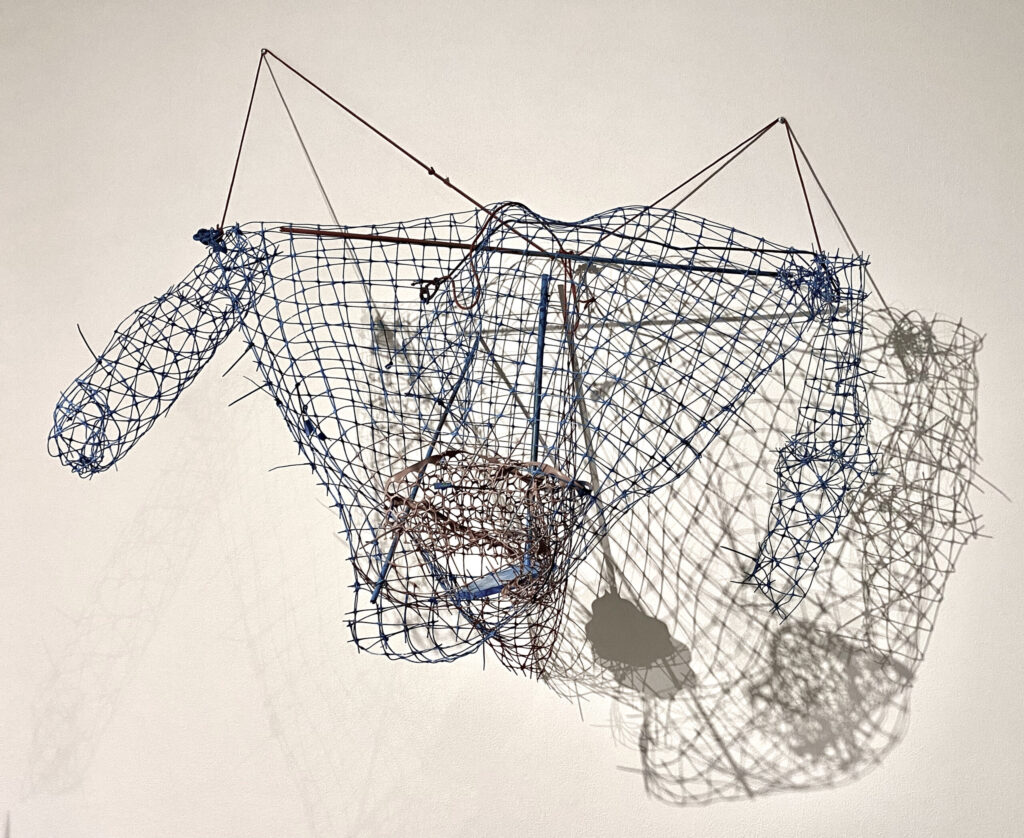

Immediately to the left, suspended over the stairs and held together by a loose armature of hoops and tubes, is a grouping of mesh constructs. Comprised of bird netting, plastic barrier fencing, cords, wood, polypropylene sheeting, zip ties, bent plywood, and what appears to be garden hose, they are – to varying degrees – somewhat ungainly and unsettling. Are they wounds or repairs turned inside out, or the bunched hems of bespoke garments? Here and there, as if they have somehow become attached or sutured, bulbous addendums are affixed to the margins. Resembling small tumors, detritus, or barnacles, they help foster the sensation that we are looking at the underbellies of these objects, or that they have been flipped inside out and these surfaces are their chaotic viscera. If these constructs correlate to our bodies, our frailties are unflinchingly visible.

Yet because they are suspended, gravity divulges an innate grace; the intricate shadows they cast are captivating. Tanner, ever engrossed in the paradoxes of dualities, asks us to look, consider, then look again: is what we think we see what we actually see? Hanging on a perpendicular wall, one work particularly beguiles: Blue Mesh with Arms, in spray-painted Aegean blue bird netting. The form is familiar, pleasing, and difficult not to anthropomorphize, yet it is not the thing it echoes. Resisting the temptation to find analogs and figurative representation allows for a richer and more curious experience; these objects and forms don’t need categorization in order to justify their existence. Repeatedly unfolding throughout Tanner’s installation is the pronouncement that definition is not necessarily destiny.

Foreordination seems at first a given for Blue Box Trap. Perched on wooden footers, this painted and carved styrofoam form is girdled and held in place with two slats of wood that form a horizontal X across its top, like the controller for a marionette. There is, however, no puppeteer in sight. Tanner says that she often thinks of an offstage character, something or someone hidden in the wings – à la Waiting for Godot – emanating a presence. Whether we call it God or time or fate doesn’t matter; in fact, to name it is to see it diminished and is pointless because the thing is ultimately unknowable. This unnamed specter – not necessarily a menace, but not necessarily an ally – haunts all of Tanner’s work, just as it haunts the lot of us. If the last year has taught us anything, surely it is the realization that despite all of our accumulated knowledge, advancements, and cultural triumphs, our bodies’ innate fallibilities leave us – and the futurity of human civilization – dangerously susceptible to the random, dispassionate machinations of other forces in the natural world. Nevertheless, we must and do endure, independent, to some degree, from those forces’ dictates. Absent a custodian, perhaps the carved portions of Blue Box Trap embody a fierce clawing at new forms of agency.

Directly ahead is Floorwalkers, a large construction of plain and painted plywood pieces intermingled, slotted, and screwed together. Pulled and manipulated from her drawings, the amorphous shapes are part of Tanner’s general vernacular. Possessing an undeniable makeshiftedness, the prosaic materials are elevated by cascading curves, scalloped edges, and a sophisticated palette of ochres, umbers, charcoals, turquoises, and cobalts. Tinted by roaming tendrils of pigment, rising cylinders of vinyl loom like minarets. Some elements support, others clasp, cling, and meander; all endeavor toward some enigmatic resolution that remains just out of reach.

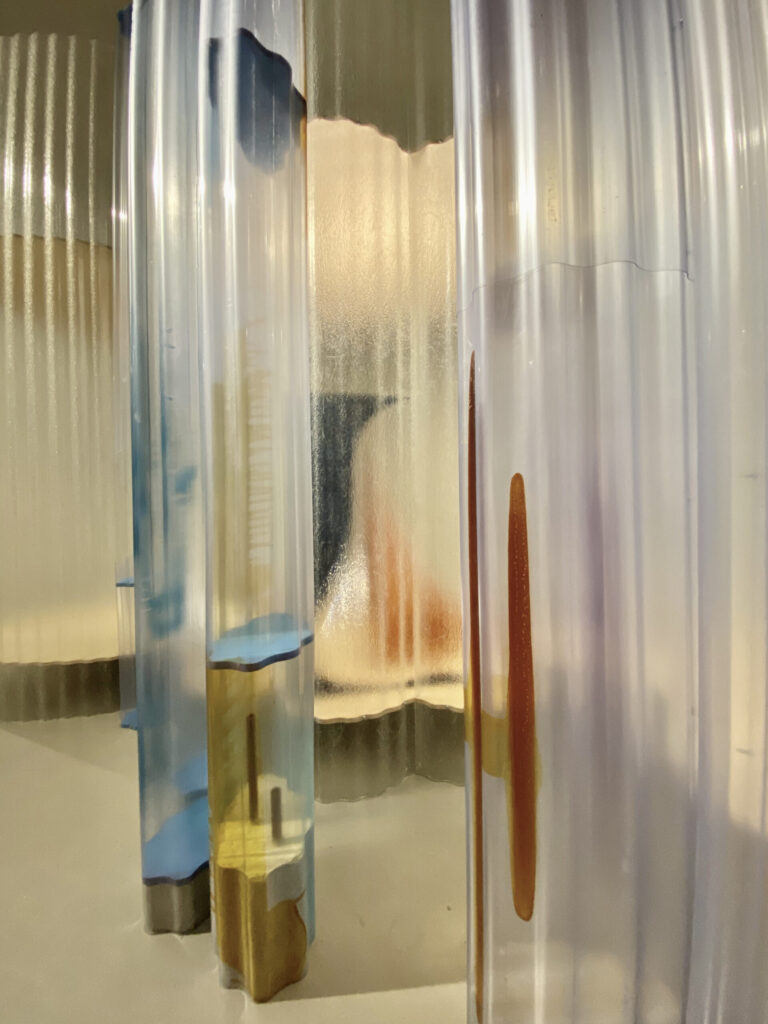

In rhythmic, undulating waves of corrugated fiberglass and vinyl panels, Tanner has cocooned two of Hadid’s aforementioned concrete supports, in the process of supplanting and obscuring their functional austerity with impressions of buoyant optimism. Interspersed at various intervals are tear-shaped objects and cut-to-form jigsaw pieces that follow the volumes’ contours; concrete formations of the same type provide footing, and there is a marvelous tension between the various elements. Luxurious and jewel-like, these translucent Bloated Columns transform impediments into assets. They feel of the future. Proclaiming their own radical architecture – these are building materials, after all – the pylons call to mind Mies van der Rohe’s unrealized 1921 Friedrichstraße Skyscraper Project in Berlin, which also looked hopefully toward a world to come.

Shaped like giant calipers, a loose grouping of large constructions, including a towering pair of drooping sentinels, idly guard the approach to the gallery’s rear. These works feel not just individual but like individuals, as if each could measure a different giant thing. They attend to Flex Rings, the exhibition’s apogee, a playful, boisterous aggregation of materials and forms that commands inquiry. Teeming with raised articulated metal track, ropes, shaped plywood elements that have been soaked in bathwater to allow for bending, additional corrugated vinyl columns, and fringed skirts of bonderized sheet metal, Tanner has deftly utilized the entirety of the twenty-four foot vaulted space to create a work that feels exploratory, expansive, even cosmic. Each successive glimpse reveals new delights. Nothing feels accidental or lucked into, but there is a sense of haphazardness, as if informed decisions have been made on the fly. All of it feels temporary, or at least precariously fixed, as if it could change tomorrow or in three seconds as realities change. This is but one possibility amongst a field of infinite possibilities. Not just rife with peril, existence, Tanner reminds us, is also joyful and absurd.

Playing with the expectation that all of these elements are dependent upon only its stability, she has left Hadid’s final concrete support – which Tanner refers to as “the spine†– exposed. The true “spine†of this assemblage is the Flex Track – repetitive metal shapes linked together and generally used in construction to create curved walls, staircases, soffits, and complicated round radiuses – that winds around like exposed vertebrae from an ancient, unearthed beast. One of Tanner’s guiding conceptual principles is that pattern and repetition do not necessarily equal sameness. As is the case with the netting and mesh – which are produced with reduplicated squares – each piece of the Flex Track is an identical and seemingly infinite copy of that which came before it, yet each piece does not necessarily do exactly the same thing. A shift in direction asks for, and receives – inasmuch as is possible – flexibility. We cannot know what a thing can do, or is capable of, until circumstances provide opportunity. Because the cycle of disintegration and rebirth abounds in the universe, all things are what they are, what they were, and what they might become; a petrochemical product, Tanner’s plastic netting was once, perhaps, brontosaurus flesh.

Although we don’t fancy envisioning ourselves as collections of atoms hurtling through the universe’s great expanse, this is, scientifically speaking, very much the truth. That we live, breathe, think and create is kind of a miracle. Tanner’s work is not based in theology – in fact, it transcends dogma and is nonpartisan in the sense that it hovers beyond any ism – but it can be seen as an imploration for us to recognize, reckon with, and accept our inherent flaws. Rejecting any illusions of certainty, Tanner invites us to consider the boundless possibilities for both space and ourselves. Yes, we must operate within certain frameworks – the laws of physics, for example – but we also largely make the world in which we live. How is ours organized? And why is it so? How can we change the things we want to change in order to better it? As always, the answers lie in incessant presentness and discerning action. Demonstrating resourcefulness that promises to be advantageous in the future but is also useful – even necessary – now, in our pandemic-ridden reality, Tanner stretches and bends her materials, engaging them on her own terms, even though they hold fast to their own ideas. Some things remain shifty and unknowable; that is okay – we probe anyway.

Art is born from a distillation of experiences; the best artists keep one eye fixed on the past, one eye fixed on the present, and their third eye fixed on the future. FLAW makes evident Tanner’s enlightened grasp of the human condition’s complexities; here, in this liminal room, she compels us to be nimble and generative in order to be prepared for whatever the future brings. We don’t yet know what it is that comes this way, but our instincts, laden with the imprint of humanity’s vexing and menacing history, sense that something lurks over the horizon, its hour come round at last.

FLAW is on view at the Contemporary Art Center in Cincinnati through August 8, 2021.