Familiar, idyllic faces are the focus of Deborah Whistler’s new series A Siren’s Kiss now on view at Moremen Gallery in Louisville, Kentucky. Replicating figures from well-known historical paintings – Botticelli’s Birth of Venus and Primavera, and Fragonard’s The Swing – Whistler has pulled these female figures out of their original environments and used them as the characters in a new mythology of her own making.

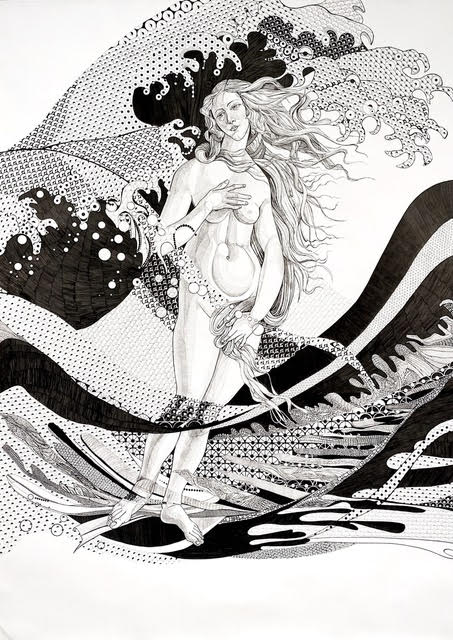

It’s disarming, the way you instantly recognize the figures Whistler has recreated. Entering Moremen Gallery, the first images you see are life-size reproductions of the young woman from Fragonard’s The Swing and Botticelli’s Venus. Titled Flirting with Danger and Taming the Sea, the works are shown as a diptych. Perfectly copied from their original environment, the two figures feel pasted in their new frames, united by a pattern of waves that crash around them. Amongst her other drawings, the Venus figure shows up again surrounded at times by cut paper or a cornucopia of flowers. Other characters from Botticelli’s Primavera also make their appearance including his Graces and the nymph Chloris. Aesthetically we can appreciate Whistler’s replication of these famous portraits – and it is easy to lose oneself in her fine lines and swirling patterns – but apart from an aesthetic triumph the why remains. Why would Whistler choose to spend so many hours recreating the figures of these old masters – what is she attempting to prove or trying to gain by replicating and relocating these female figures?

Outside of the replication of these famous faces, there are clues that hint at an underlying storyline existing amongst Whistler’s new series. Repeating vines of flowers and insects and a recurring circular shape serve as a gentle hint of the interconnectedness of the works, but it is the accompanying text that assists the audience in identifying the key features of the story. For each of her pieces, Whistler has written a short poem to help narrate and to allude to small hidden details that may initially be overlooked.

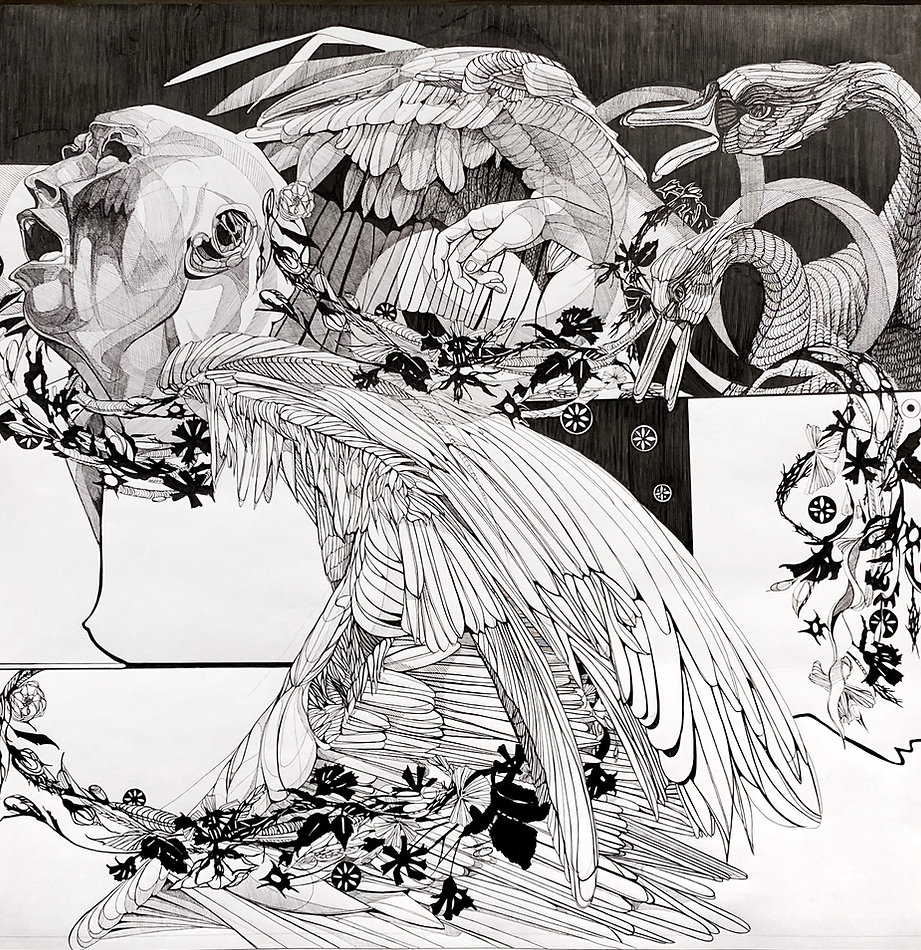

Within Flirting with Danger the image of a swan has been carefully drafted into the folds of the swinging female’s dress – an easily overlooked detail if not for Whistler’s line: “Not only will she miss the crashing of this Great Wave but she will use the vacuum caused by this surge to ditch the swan hidden under her skirt at the same time.†This same – decidedly unwelcome – swan is seen again in Clipping the Wings of the Siren, where its previously docile nature is exposed as a trick. In Clipping the Wings of the Siren the swan’s head rears, its body poised to attack. An arm springs from its breast as if it transforms from animal to human. In this work, Whistler has succeeded in creating a dramatic and emotionally charged piece, using a vine of flowers to guide the audience from the swan, around to the screaming face of the siren and under its wings. In this image, the “siren†has been recreated from a sculptural work by Rodin. Here the head of Rodin’s The Scream is presented in profile to represent the pain as the Siren loses its wings.

The next line Whistler writes in the Flirting with Danger text: “Her focus is on one spot that she balances between her fingers†serves as the translation for the recurring circular spot seen through Whistler’s works. This spot is meant to serve as a guiding source of strength for the swinging figure and it appears again in Vulnerability where the portraits of Botticelli’s Graces have been recreated. Removed from their lush garden, here they rest on a flat white background, their gazes fixed on this tiny circular spot. In this instance the spot seems similarly to be representative of strength, serving as a guide for the Graces or a hope of freedom from their endless dance.

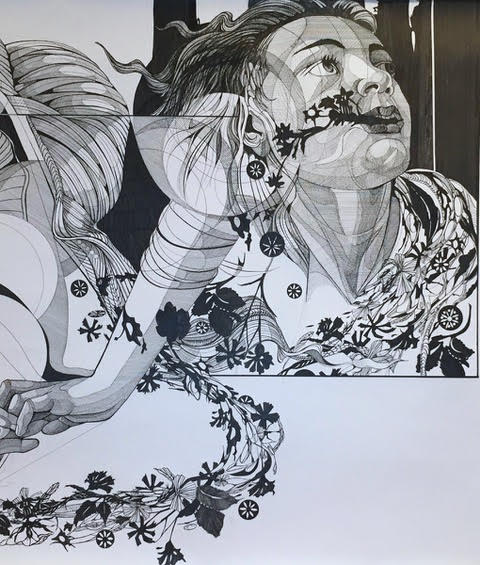

In this way, her recreations also feel like an attempt at rescue. Is the spot the source of their transference from one environment to another? In her work A Siren’s Kiss, the composition focuses on the head of Chloris – as depicted in Botticelli’s Primavera – at the moment of her abduction by Zephyrus (God of the West Wind). The vining flowers escaping her open mouth allude to her eventual transformation into the Goddess Flora. In the original myth, Zephyrus rapes Chloris, makes her his wife, and then as a gift grants her dominion over flowers. Pulling Chloris out of Zephyrus’ grasp removes her from the storyline of having to be abducted and raped before she can become a goddess. Instead, in Whistler’s depiction, she seems to transform of her own volition or, in other words, she is able to use her own strength to give life, her own breath to pollinate the world.

In paintings that were once about the female figures as objects to behold, Whistler’s copies of them are meant as an attempt to allow them to reclaim their power. To shed their objecthood and become autonomous in their own stories: as givers of life, as sexual beings, but mainly as strong women. She has even reclaimed the mythical figure of the Siren – once a monster disguised as a woman to lure men to their deaths – now a deity of Spring. To accompany her drawings of the women, Whistler has created beautifully drafted drawings of bees and cicadas hinting at the continued cycles of life and death, spring and winter, and the cycles of women and the ability to give life.

Through all of this, Whistler’s exhibition celebrates the feminine. A feat she accomplished by, as noted, removing her female characters from their original spaces. In their original environments, their space was inherently masculine – disguised as an ocean view or a lush garden – but meant for the male gaze and meant to restrict the movement and control the figures being represented. In relocating them, she transfers them to a no-place, an environment devoid of background or context, but one that is still not without its inherent dangers. The Siren, after all, still loses its wings.

The curatorial text for A Siren’s Kiss notes: “In a cultural climate where female sexuality and beauty is often constrained by political correctness, Deborah Whistler’s works burn through conventional ideals with all the fiery passion of the siren’s kiss.†It is difficult to reconcile this line in an exhibition about “burning through conventional ideals†when the figures recreated are all from representations of ideal beauty. And perhaps this is why it feels so difficult to get past the continued copies of these idealized masterworks and focus on the underlying theme of the exhibition.

While Whistler’s goal was to celebrate female empowerment and sexuality, one cannot help feel that it falls short by constraining that female empowerment and sexuality around idealizations of beauty. In fact, repeatedly using the figure of Venus feels more like it is reinforcing that traditional female tropes – beauty, fertility, love – are inherently fragile, and that only those who fit into these idealized forms are worth empowering. While it is noteworthy to create a body of work that seeks to celebrate female sexuality, by holding on to these original idealizations, even after relocating the figures she maintains the point of their original creation – to serve as ideals for the male gaze.

Deborah Whistler’s “A Siren’s Kiss” is on view at Moremen Gallery in Louisville, Kentucky, through July 17, 2021.