One of the great gifts from both art and nature is their ability to reacquaint us with the act of seeing – to look at an object before you with a focused presence free from digital distractions. The surge in virtual forms of art viewing precipitated by the global pandemic has only increased my appreciation for that unmediated experience, so I was as surprised as anyone to find myself stumbling across the lawn of the Laumeier Sculpture Park last July with my eyes locked on the iPhone screen in my outstretched hand.

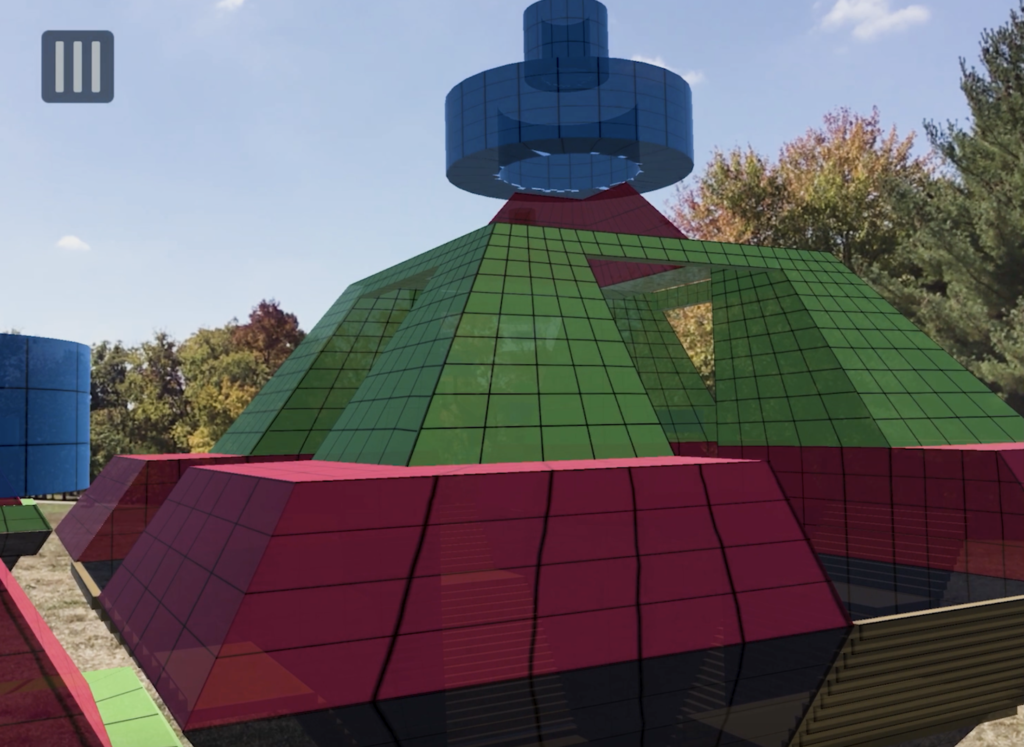

It was a swelteringly hot afternoon and I was there to see Time Fork, an exhibition by artist Van McElwee. It uses augmented reality to reveal digital sculptures situated among the 70-plus physical works that occupy the park’s 105 acres of undulating lawns and dense woodlands in St. Louis County. The installation springs from the premise that somewhere around 1054 C.E. – simultaneous with the celestial appearance of Supernova 1054 and the rise of the Cahokia settlement in nearby Southwestern Illinois – time branched to create a parallel world that continues to unfold along the same timeline as our own humble existence. After I downloaded the Time Fork app, I was able to investigate the digital artifacts of this alternate reality, moving around and passing through virtual mounds, totems, and temples as if I were a ghost of an ancient, analog civilization.

Interestingly, McElwee’s imaginary additions to the landscape share similar references with other site-specific commissions in the collection: his primary-hued ziggurat renderings, for instance, recall both the Mayan temples that inspired Jackie Ferrara’s wooden, pyramid-like Laumeier Project and the mound-building cultures that informed Beverly Pepper’s earthwork Cromlech Glen. Accustomed as our society is, however, to the remarkable detail, subtlety and verisimilitude of contemporary computer-generated images and video, the structures in Time Fork are realized in a more elementary manner. The result is an overlay of brightly colored, translucent structures that are never fully convincing as a concurrent presence.

Still, the installation succeeds in arousing questions about the nature of sculpture, space and form relevant to an increasingly digital world: must spatial relationships always be physical? Can they straddle virtual and temporal dimensions as well? The digital objects in Time Fork assume familiar architectonic shapes and three-dimensional forms (albeit viewable only on the singular plane of a smartphone screen), and the artist has purposefully placed them in relation to other physical objects. And while the exhibit is highly ephemeral, in the end, so too are the sculptures that it overlaps, made as they are of materials that will erode and decay: even reinforced steel eventually gives way to the effects of weather and time.

Indeed, the greatest achievement of Time Fork is its capacity to make everything look like the remnant of a collapsed civilization. I had visited the Laumeier previously and was familiar with many of the works, but after closing the Time Fork app that afternoon, the objects around me suddenly became unfamiliar and strange. Tony Tasset’s giant fiberglass Deer and Eye – what were they? An accurate depiction of the prehistoric proportions of the local fauna? A ceremonial offering to the gods of sight and vision? And what about Mark di Suvero’s Bornibus, that huge and precarious composition of steel and cable? Surely this must be the relic of some bygone industrial culture, ultimately undone by its own manufacturing hubris. No longer could I see The Way, Alexander Liberman’s monumental work of salvaged oil tanks painted in the kind of vibrant red generally reserved for religious rites and rituals, as anything other than a modernist temple.

Dizzy with the delight that a new perspective brings, I set off for a wooded area of the park I hadn’t yet traversed, map in hand as if I were a youthful explorer on a scavenger hunt for hidden treasures. One of my first encounters was Harriet Bart’s Without Words, A Reading Room, an archaic diorama of sorts in which five boulders the size of sitting children face an empty metal podium on a concrete slab; behind the boulder is a stone wall on which the letters AEIOU have been chiseled. The scene evokes both esoteric mystery and playful innocence, equally believable as a child’s backyard imaginings or the relic of arcane gatherings.

From there, I followed the nature trail around another bend to find the extravagant Orchard Valley: Pool Complex, a sprawling expanse of pine, steel and concrete pavilions, platforms and staircases designed by artist Mary Miss at the site of a lavish swimming pool – originally converted from a large pond – that had long since been abandoned by the estate’s owners. And while Miss’s constructed ruins inevitably invite ideas of the passing of time, mortality, decline and decay, on that afternoon I couldn’t resist the notion that I had somehow stumbled upon some secret playground that had shown itself only to me – a poolside Narnia hidden within the forest.

That spirit of adventure carried me to what would be the final work I would see that day: Beverly Pepper’s Cromlech Glen, an earthwork inspired by Pepper’s visit to the expansive Angkor Wat temple in Cambodia. Here, nestled in a clearing in the Laumeier’s Eastern Woodland, two grassy mounds rise, gently imposing, above the wandering human, offering their worn sandstone steps as an invitation to ascend. As I climbed the mounds, my surroundings seemed to take on a technicolor presence: the grass so brilliantly green, the sky its own cerulean perfection, the birds circling overhead singing their prehistoric melodies. At the top, I realized what I had been climbing were not mounds at all, but the sides of a tall earthen bowl, its verdant interior offering me a quiet refuge shrouded by a lush tree canopy. I had spent the previous two hours contemplating the eventual decay of every human-made object, yet it was sitting on top of this ancient architectural form that I felt not the presence of past generations, but simply the force of my own: I had remembered how to see.

Time Fork is on display through October 10 at Laumeier Sculpture Park in St. Louis, Missouri.

Top Image: Van McElwee, Time Fork, 2020. Concept, Design, Producer, Director: Van McElwee; 3D Construction: Casper McElwee; Augmented Reality: Rampant Interactive; 3D Drone Mapping: Mike Rosenthal. Images captured by Foveal Media.

​