My first thought when I entered LaVon Williams’ studio was quickly confirmed by him – yes, he was preparing for a show. The room had rows of carved wooden statues, panels stacked against the wall, and posters prepared with his artist statement and biography. Oh, and wood chips.

He is heading to Paducah for a show of his latest collection, called COVID.

Williams worked on this collection in the deepest part of the pandemic. As he explains, the world situation put him in an agitated state, and he created a lot of work. “I needed to get something out without screaming, but I rushed it,†he says. “It was too dark of a place to be.â€

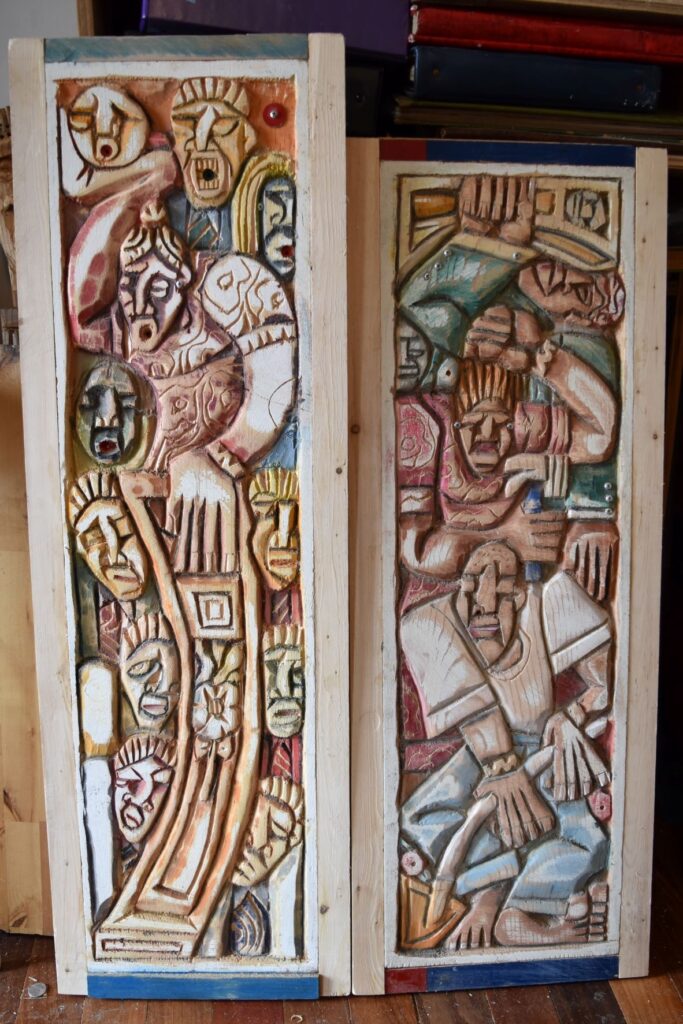

Thankfully, Williams is in a lighter place now. He has since reworked the pieces, sanding them down, adding more detail, and lightening the mood with color.

What they retain is an intensity, a sense of urgency. “Call My Name†and “Making Boxes†were based on George Floyd’s death and the deaths of so many more people of color across the country. They feature mothers crafting coffins for their children and men holding shovels to dig graves. The faces reveal deep sadness and lamentation.

Pieces like these in his COVID collection are divergent from his usual work. “Three Girls from Detroit,†based on Diana Ross and the Supremes, is more typical of his carvings. It is colorful, upbeat, happy even. It makes the viewer smile. Music and musicians are two of Williams’ signature themes.

The collection proves his ability to carve works full of life and movement, whether that life is celebrating raucously or in painful lament. LaVon Williams is a man of few words, but his art speaks for itself.

***

Williams is seeing his first commissioned public outdoor art project come to fruition, a series of outdoor plaques at the Isaac Murphy Park in Lexington. Murphy is one of horse racing’s most decorated jockeys. He is also one of its most forgotten, until a recent groundswell reviving the history of Black jockeys in the early days of Lexington horse racing.

The art project is a series of six 2’ x 4’ carvings about Murphy’s life cast in iron placed around three benches. He has completed two rough carvings. “Race Man†has Murphy and other Black jockeys astride their steeds. In “Lucy and Isaac,†the artist depicts the love story between Murphy and his wife Lucy. Williams points out that, often, stories about accomplished men leave out the stories of women.

Williams looks forward to the completion of the project. “It will be so powerful, people from all over will come to see it and take pictures with it,†he says.

***

Williams learned his craft from his uncle and brother, both of whom were master woodcarvers. He was young, in elementary school, and growing up in Sanford, Florida, when he first picked up a chisel. He adopted their style, unique to the deep South. People compare his pieces to Haitian or African art, but he is quick to point out he sees it as part of this Southern tradition. “They are like cousins, similar but not the same,†he says. “The South is where all the good stories come from, stories of both kindness and sadness.â€

When Williams was in high school, the University of Kentucky recruited him to play basketball. He was a member of the 1978 team that won the NCAA national championship, then played professionally overseas for a couple of years after graduation. He came back to art in the 1980s and hasn’t looked back. “Basketball was a stopping place for a while, but art was my first love, since I was a little kid,†he said.

An attempt to return to school for an art degree proved fruitless. Williams was already showing his art nationally in the same places as his teachers. With their encouragement, he decided to pursue his own direction. That has taken him into a process of learning through trial and error and solidifying his place as a folk artist, with a twist. In contrast to many folk artists, Williams’ pieces reflect city life and an urban sensibility.

***

Being a folk artist does not mean Williams doesn’t take his art seriously. Bookshelves line his studio behind the proliferation of carvings. The books are about other artists, from Picasso to the Harlem Renaissance, and he draws upon them for inspiration and technique.

Williams’ brother was his biggest artistic influence. After his brother’s passing, Williams inherited many of his carvings. He studies those and observes his own mistakes. “I draw all of the time,†he says. “It is a constant process to stay on top of my talent.â€

The tools and materials for Williams’ work are uncomplicated. Carving requires only three sizes of chisels (2â€, ¾â€, and ½â€), a couple of weights of mallets, and two V tools. He is not picky about the type of wood he carves, often using whatever is available.

Once he has a piece of wood, cut roughly in the shape he desires, he formulates the design. He transfers it onto the wood in pencil. He then begins to carve. The skill is ingrained; the amount of pressure, the correct weight of mallet, the angle, he does by feel and not calculation.

***

Through his art, Williams seeks to pass on his cultural tradition and illuminate African American history. As he shares the stories and techniques behind his work, he hopes to inspire more people to buy original art.

Williams has received numerous awards. In 2007, he was awarded the Kentucky Governor’s Award for lifetime achievement in the arts. He was inducted into the UK College of Arts and Sciences Hall of Fame. He had a solo 25-year retrospective in 2001, “Rhythm in Relief,†at the Kentucky Folk Art Center in Morehead.

Ultimately, though, his purpose and validation come back to the work itself. “Awards don’t mean much to me. Art is what means a lot to me,†he says. “I think, and breathe, carving.â€

LaVon Williams’ work can be found at Art House Gallery in Lexington.

All photo credits: Kim Kobersmith