The Louisville Photo Biennial began in 1999, and the quality of its offerings this year was better than ever. The brainchild of lawyer, collector and gallerist Paul Paletti, the photo biennial for 2021 had over 50 participating venues and extended its geographical reach to Frankfort, Lexington, and Springfield, Kentucky. Fourteen galleries in southern Indiana also took part. Guided tours, artists’ talks, and workshops for professionals complemented the exhibitions.

For Paletti, among high points this year was the exhibition and keynote address by Keith Carter, which was particularly well received by working photographers. The Speed Art Museum provided marketing expertise and donated space for Carter’s lecture. The Louisville Photo Biennial trades off with Cincinnati’s Photofocus, which occurs in even-numbered years. A symbiotic relationship between the two festivals is evidenced by Cincinnati bringing its patron groups to Louisville, along with some monetary support. Louisville’s effort struggles along with part-time employees, dedicated volunteers, and a $30,000 budget mostly made up of very small contributions, while Photofocus has a professional staff and an annual budget of $1,000,000. The Louisville organizers need to find more stable, long-term sources of income. Coincidentally, collectors dedicated to local or regional photography could assemble museum-quality holdings with modest outlays but, so far, such collectors do not seem to exist.

Paletti asserted that 2021 has been a pivotal year, with high levels of public awareness and engagement. Here are some keynotes. Four shows documented in depth the Breonna Taylor demonstrations. At Asia Institute Crane House, Dr. Brett Erickson curated an international group of sixteen artists investigating five concepts in Japanese aesthetics. The Speed Art Museum displayed a new acquisition, a portfolio of Ralph Eugene Meatyard’s moody, portentous, private reflections on Red River Gorge. Moremen Gallery showed Zed Saeed’s American Nocturne series, hyper-saturated color studies, uncannily reminiscent of stills from early Technicolor movies. Pyro offered two shows. First were C.J. Pressma’s and John Nation’s road pictures taken on their 10,000-mile peregrination through the West and South. Their character studies were especially memorable. Next came Keith Auerbach’s and Amira Karaoud’s images of France. Auerbach’s candids of French cafés and their patrons are psychologically complex studies of love, friendship, family, and isolation in public/private moments. Relationships between servers and those served add another narrative layer to these mini-dramas. The show’s imagery was a welcome antidote to months of COVID-induced isolation.

Among many rich offerings, I was intrigued by Joe Wolek’s show at Galerie Hertz, the work of a relative newcomer locally. Born in Louisville, Joe Wolek returned to his hometown after several decades in Los Angeles. He showed two series, On the Beaten Track and Loose Wanderings in a Rigid Terrain, the first set in the suburban American West and the second in rural China.

On the Beaten Track extended the aesthetic of the photographers featured in the 1975 exhibit at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, The New Topographics. Participants in that show included, among others, Robert Adams, Lewis Baltz, Joe Deal, Frank Gohlke, and Stephen Shore. A recurring subject among those artists was the spoliation of pristine landscape by tract housing, often seen from a distance so that the contrast between the new and the natural was sharpened.

On the Beaten Track was a 2015-2017 by-product of location scouting for a Harley-Davidson promotion. Empty parking lots, shopping centers, and the fringes of highways were the seemingly austere and spare subjects. Although set in the American West (echoing themes of The New Topographics photographers), the focus was the archetypal American anywhere, characterized by expansive anonymity and the ironic barrenness and desolation effected by misspent values and misspent wealth. The photographer remarked, “The pictures investigate a certain underbelly of society, alluding to the fall of the brief reign of celebrated middle class culture and attempt to expose myths of its nostalgically cherished integrity.â€

Wolek posited a more pointed critique of capitalist excesses than his predecessors. His large panoramas (up to seven feet wide) are made with a series of shots taken with a telephoto lens that are then stitched together to create a uniformly high-focus, compressed field of vision. Closed Big Box Store was a blunt commentary on the vagaries of corporate fortunes and marketplace shifts. Used yellow plywood covered the building’s façade, the wood grain of the boards patterned with watery rivulets like marbled paper.

This panorama of abandonment shows four bays of the closed store with parts of two others at either end, suggesting a far longer continuum. Two sheets of plywood line the top of the image above a red girder. Two and a half layers fill out the space below, arranged between five concrete columns with deteriorating plaster. The expressive point and counterpoint of the repeated geometries endowed the former retail site with a distilled intensity. Weeds sprouted in the crevices of the sidewalk beside the wall. The roadbed in the foreground covered approximately a third of the picture surface, the serpentine lines of tar in the asphalt echoing the plywood grain. Closed Big Box Store was simultaneously an exquisite exercise in formal abstract order and an excoriating indictment of late-stage capitalism. Wolek underscored confrontation through granular examination of the deteriorated site, the wide scale of his work and its flattened space.Â

Like other practitioners of Minimalism, Wolek relies on proportion, interval, and repetition. His compositional methods echoed the sculptural stacks of Donald Judd or the music of Philip Glass. The composer’s Glassworks was described as “sharp hard sonorities, densely packed, slowing changing patterns and seemingly unstoppable linear flow.†As commonplace a subject as the deterioration of malls ought to be tedious, but in fact, the contrapuntal rhythms of Closed Big Box Store were very immersive.

Grocery Carts was also composed as a series of horizontal strips. Another panorama, it also used a high horizon to flatten the pictorial space. Horizontal zones were lined out. A file of 146 grocery carts was seen against a wall of light and dark beige bricks. The beige blocks had a faintly regionalist Californian/Mediterranean stucco or adobe hue, but the extended wall and the long row of attendant carts were so quintessentially and universally American it was hardly particular to a specific locality or region. There was an intimation of enforced conformity in Grocery Carts. The viewer was forbidden access to opportunities beyond the wall, but the grocery carts suggested that the viewer might be called to take up a cart and enact the consumerist ritual of cruising the aisles.

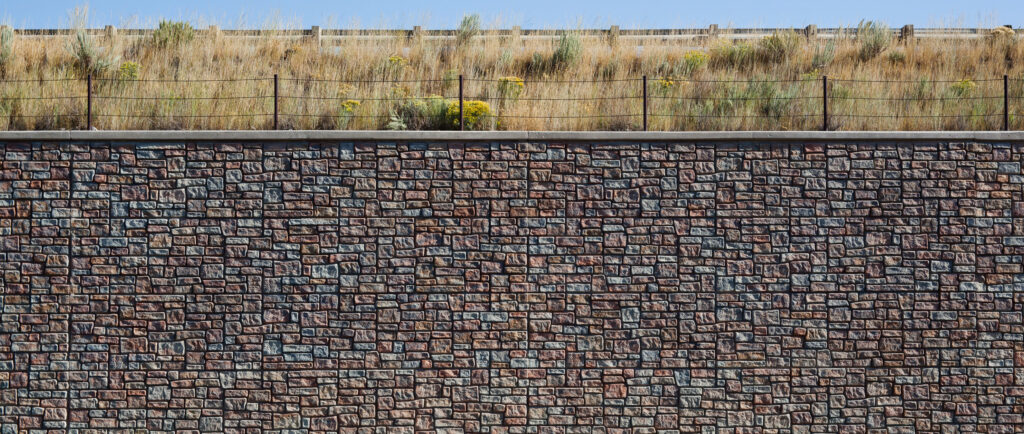

A third investigation of urban but anti-urban spaces was Freeway Wall, a study of the leftover and marginal spaces aligned along major highways. Exclusion was again a primary motif. An obdurate wall of purple-gray cast concrete, textured to resemble stone, dominated. Above the fake masonry was a passage of sandy dried grasses with intermittent spurts of green, a typical dry and tonal winter landscape in California. The high wall, a wire fence, and the highway curb rail forbade possible entry: the pale blue sky above connoted a distant and unavailable freedom, as if the view was from a prison yard.

Like On the Beaten Track, Loose Wanderings in a Rigid Terrain was an incidental offshoot of a different assignment. In 1999 Wolek was artist-in-residence at the Bemis Center in Omaha, Nebraska. He became fascinated by Frank N. Meyer (1875-1918), a seedsman who collected plants almost continually between 1905 and 1918. Meyer is credited with introducing 2500 plants, including most of the wheat varietals which allowed the American western plains to become “The Breadbasket of the World.†The photographer received a grant to follow in Meyer’s footsteps in China, traveling to Mongolia and Shaanxi, Qinghai, Jilin, and Sichuan provinces. While China had opened up to the West in 1978, the remote areas Wolek traveled 21 years later remained largely fresh to Western eyes. His visit coincided with China’s advance as an international center for book publishing. Some of his most extraordinary images showed the re-purposing of book and advertising illustrations as decoration. The subject of outdoor images in Chinese interiors evolved: the photographer as tourist crossed paths with the “tourist†destinations of his Chinese subjects, extolled in the illustrations displayed on the walls. The ironies of this “double-tourism†put forth cultural multiplicity as the photographer’s thesis, displacing the much-criticized posture of documentary photographers accused of “othering†Third World people.

In The Factory Workers’ Break Lounge, Tibetan Plateau, Sichuan Province the function of the break room was highlighted by foregrounding the workers’ tables and chairs. A traditional Chinese lantern hung from the ceiling, and a traditional wooden container rested on two chairs against the back wall, topped by a galvanized garbage can lid. On the walls – painted white at the top, blue at the bottom – were two blown-up images: on the left, a large poster affixed to the wall with yellowed tape, depicting a still life with a plant in a white pot next to a luxuriant cascade of fruit pouring out of a basket. To the right, on the rear wall, also affixed with tape, was an advertising image of three lounge chairs with pink cushions surrounding a white table beneath a pink umbrella, all set within what appears to be a Western backyard patio. The formal structure of the picture gave the illustrations a secure place in the ordering of the composition, as if conveying acceptance of the odd contradictions between Chinese communism and its 1990s romance with capitalism. Jonathan Friday has remarked, “To attend to a documentary photograph is to understand what is seen…as an evidential illustration necessarily connected to a particular time, place and historical context.â€Â Realistic and reportorial, the images provided access to the aspirations of the inhabitants of the room.

Even more startling was an image from Yan’an, the center of the Chinese Communist revolution from 1935 to 1947. Near the endpoint of the Long March, Yan’an is revered as a pilgrimage spot for its historical role. Restaurant Yan’an, (Site of Mao’s Revolutionary Headquarters), Shaanxi Province was another of the indoor/outdoor juxtapositions. Menus, a napkin, and a pitcher sit atop a glass counter in the foreground. But the back wall of the restaurant purveyed an American bourgeois ideal – a forty-foot-wide image of a white neo-colonial American home, displayed in a gold frame. The image of the expansive manicured lawn and garden, the shrubbery and flowers bordering the house, the mature trees, and shutters on the windows to unite the three units of the home, all bespoke a very different milieu. Adjacent to the prosperous suburb was a partial view of a popular and more traditional Chinese landscape subject, a waterfall (an auspicious symbol of prosperity in many Chinese traditions). The linkage in theme – contemporary and time-honored versions of wealth – added to Wolek’s almost anthropological investigation of indoor/outdoor contrasts.Â

Another waterfall image dominated Train Station, Taonan, Jilin Province. Centered above a train station waiting room with a single occupant, the traditional landscape painted on tiles shows a waterfall with mountains behind receding into the far distance. The photographer took in the whole of the waiting room, following rows of red plastic chairs, resembling the Rolling Stones tongue logo, as the axis of his investigation. Because the ceiling, walls, and floor were depicted, there was a sense of containment. But ironically, there was no feeling of being boxed in. In part that was because the tall windows offered views outdoors: to the left, buildings; to the right, a waiting train car. But it also depended on the precise lateral balance of Wolek’s treatment. A puddle on the floor echoed the waterfall mural, as did the aqueous blue paint on the rear wall. A traditional Chinese circular door centered the view and played against the sole occupant, a woman dressed in black at the end of the row of seats. A sign in bold Chinese characters on the back wall extended the red of the plastic chairs, as did a second row of chairs on the right. Beyond the secondary row of chairs, two bicycles leaning on the wall were reminders that train stations serve the acts of arriving and going away. The fanciful panorama of the waterfall and mountains offered a psychological release from the down-at-the-heels melancholy of the station.

All of the photographs in Loose Wanderings in a Rigid Terrain embraced contradiction and countered stereotypical expectations. Up-to-date plastic seating changed the narrative of the Taonan train station. Similarly, one did not expect a hotel bedroom in Ulan Bator to have a Toyota calendar; or a computer store to have a sheet of traditional calligraphy; or a teahouse on the Tibetan plateau, with its crude hand-wrought bench and stool, to display five photographs of high-performance sports cars; nor did one expect Western advertising to dominate facilities serving Communist workers. By eliminating or subordinating the role of human occupants, the photographer allowed their habitations to speak for them, without necessarily stressing societal disparities between the fulfillment of private desires and public policies. What was actually visually recorded was emphasized, not how it might have been interpreted or judged. In these discordant accounts, it was not what makes the scene Chinese that counted, but how the locations all participated in international commercial culture.

The minimalist photographs in On the Beaten Track relied on implication and intimation. The pictures revolved around the distorted values suggested by the austere settings. The photographer was strongly influenced by a discussion in a class at Cal Arts taught by the conceptual artist Michael Asher, looking in detail at the difference between connotative and denotative images. Societal critique was not at issue in the images in the second series in the exhibition, Loose Wanderings in a Rigid Terrain. The contrast in the two series is roughly analogous to MOMA photography curator John Szarkowski’s distinction between “mirrors and windows.†The former are connotative, in the province of self-expression, the latter images more factual and descriptive, more about the exploration of the visual world. Strongly editorial, the images of American society profit from the sense of dislocation that Wolek’s Photoshop technique provided: the viewer’s sense of a normal network of relationships to a structure or environment was undermined by the squeezed-up space.

In On the Beaten Track, Wolek used the capacity of photography to lie in order to serve, in his words, “influential repercussions in the elucidation of contemporary culture.†Sally Mann, in her book Hold Still, used a verse by W.H. Auden as a frontispiece:

The steady eyes of the crow and the camera’s candid eye

See as honestly as they know how, but they lie.

Honesty and artistic truth are not at odds in photography, but they may be with common notions of objectivity. Wolek played in the gap between what is seen and what is known: he remarked, “There is power in photographic reality and here I try to regain conviction in how that power reveals and validates itself.†That power was manifest in the scale of the American photographs, their close focus, and finely detailed read. In his practice, Joe Wolek used subjective and objective criteria as variables, all in the service of the elusive notion of “photographic reality.†The formal rigor of Wolek’s work served divergent purposes: in America it defamiliarized the conventional, slowing the perceptual read, thereby opening an awareness of the artist’s connotative rhetoric. In China, on the other hand, the photographer’s denotative approach pared away the expressive overlay of additional meanings: the rigorously ordered compositions simply invited astonishment at the complexities of a historical moment.

Wolek’s show was immensely satisfying and rewarded extended contemplation. I went back three times and wished the show had remained up longer.

The Louisville Photo Biennial took place from September 9 through November 14, 2021. To learn more, go to https://louisvillephotobiennial.com/.