When most Kentuckians picture the Red River Gorge, the 29,000-acre canyon system of rugged rock cliffs, sandstone arches, natural bridges, and waterfalls within the Daniel Boone National Forest, the images that spring to mind are mostly sun-drenched vistas. We see vast distances at a glance, generally from on high, in which the details are secondary to a sweeping panorama. We’ve been trained to imagine the Gorge this way by several generations of professional landscape photographers whose work dwells on light and space, producing in us reliable, perhaps not overly complicated feelings of awe at the size and sheer splendor of the place.

It’s in this context that the pictures in “Ralph Eugene Meatyard’s The Unforeseen Wilderness,†the Speed Art Museum’s current exhibit of work by the late Lexington photographer, are so startlingly original. For many visitors viewing the show, which continues through February 13, 2022, the first word likely to come to mind is dark.

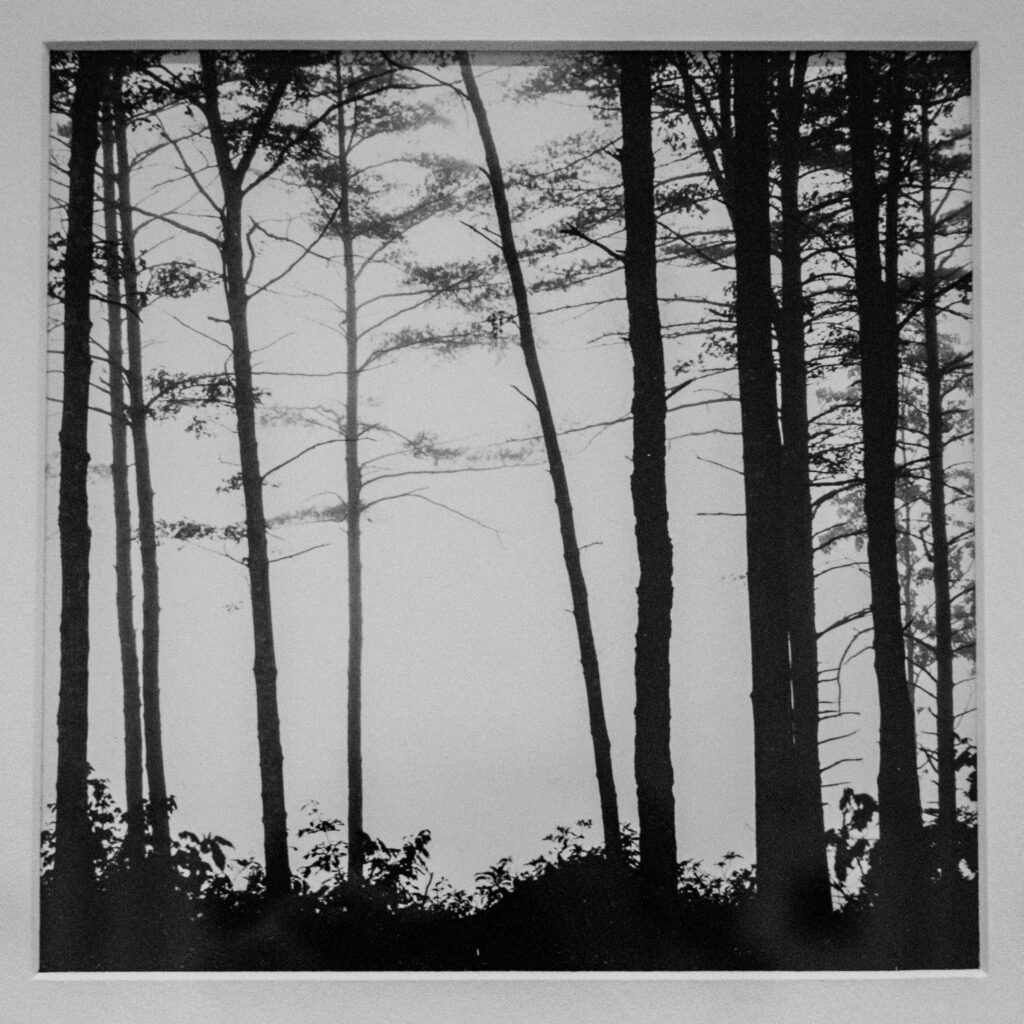

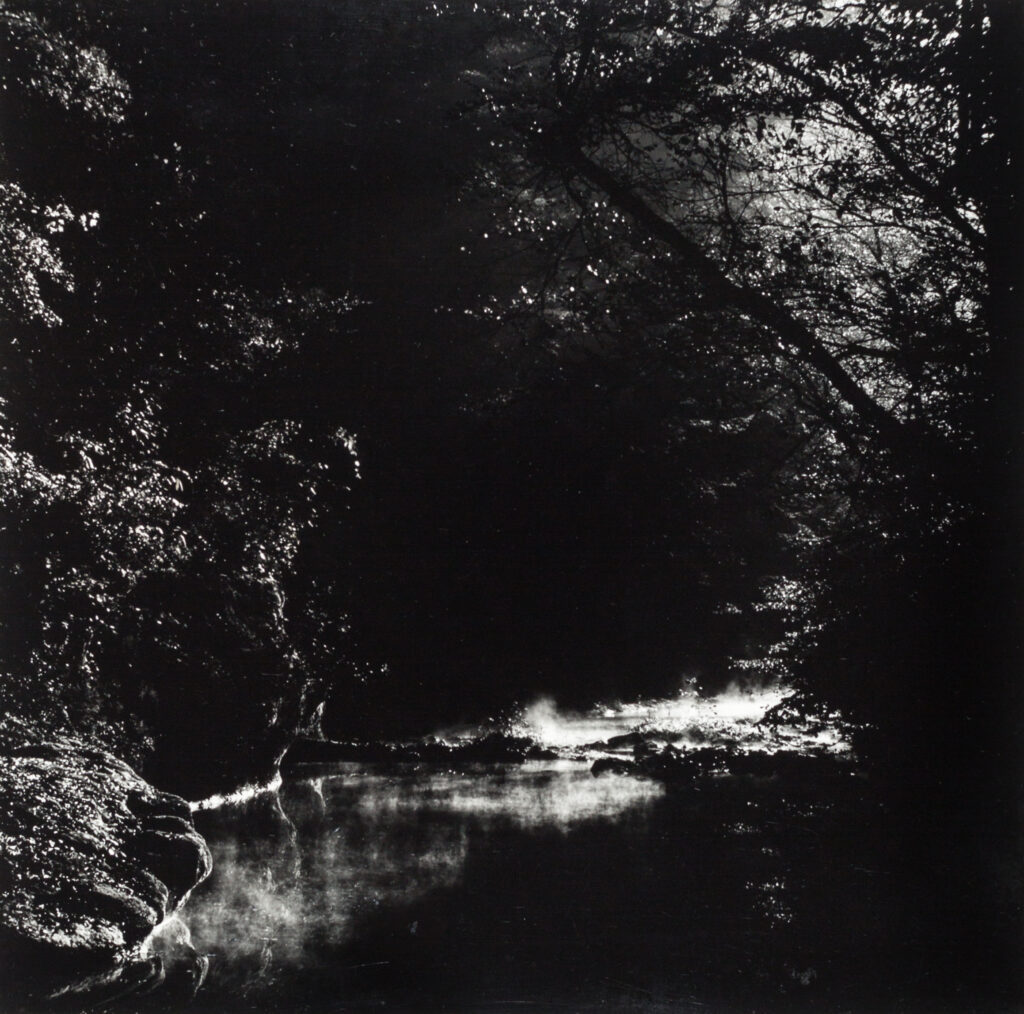

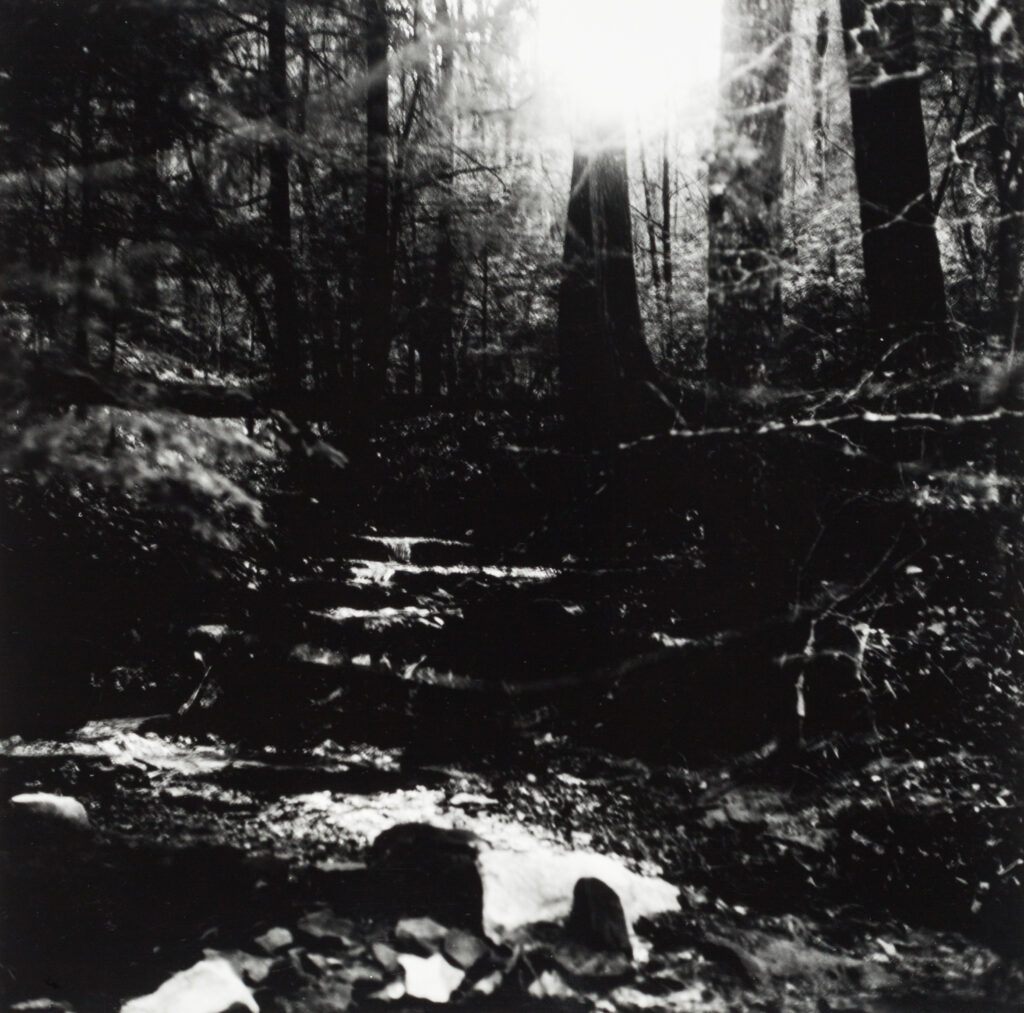

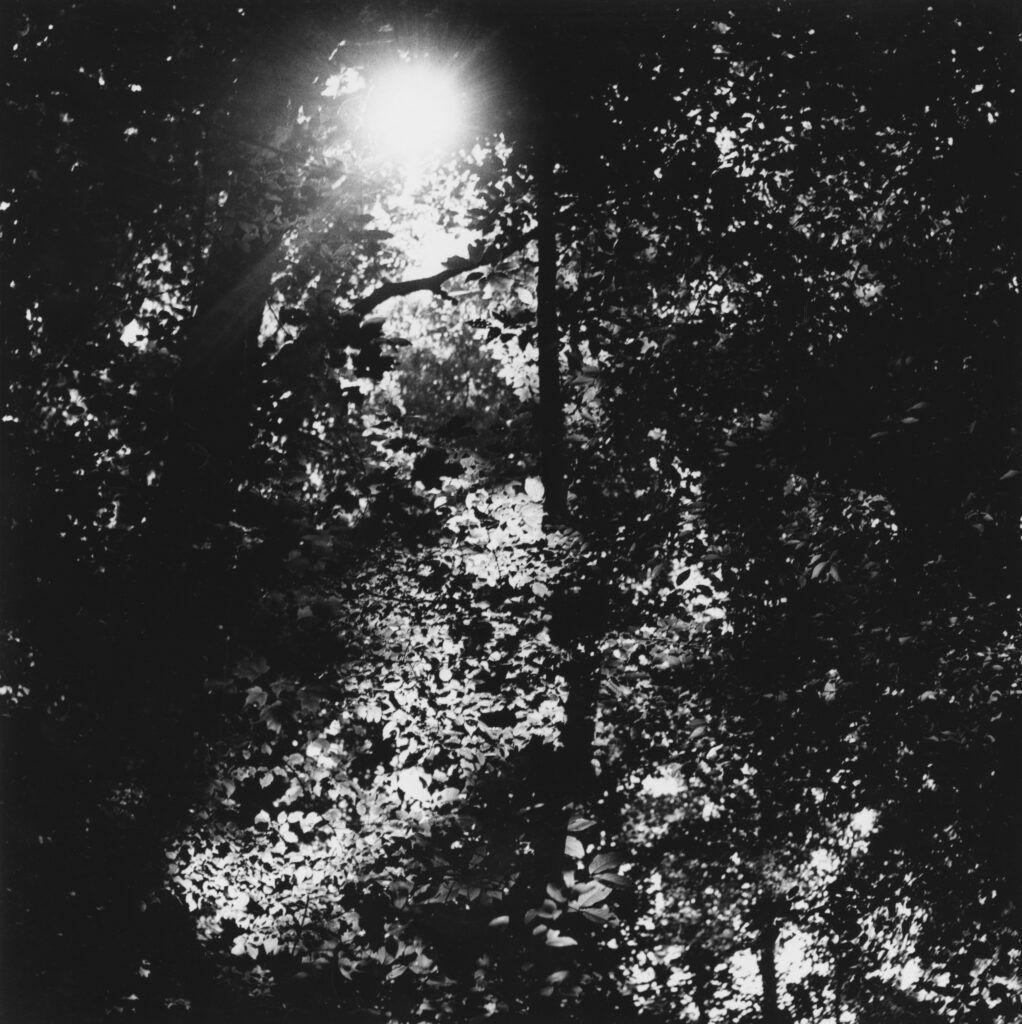

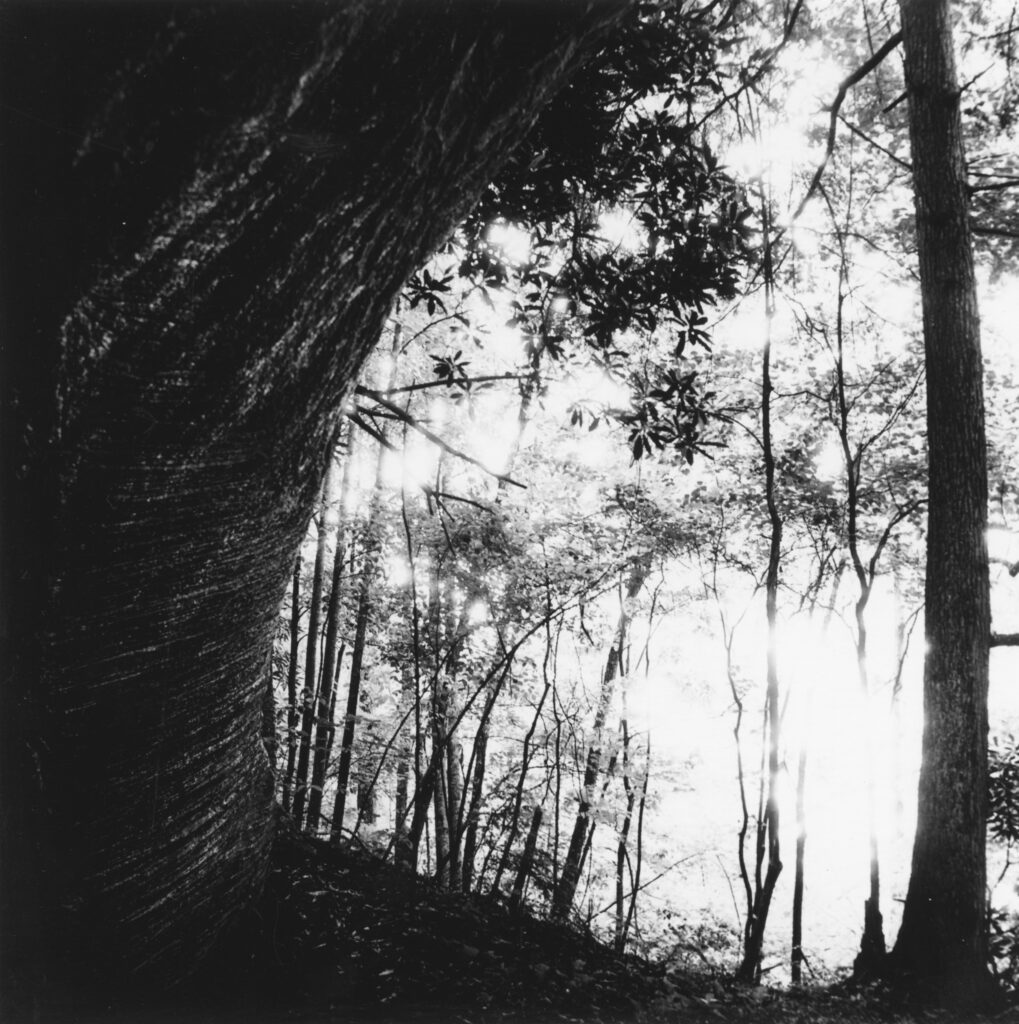

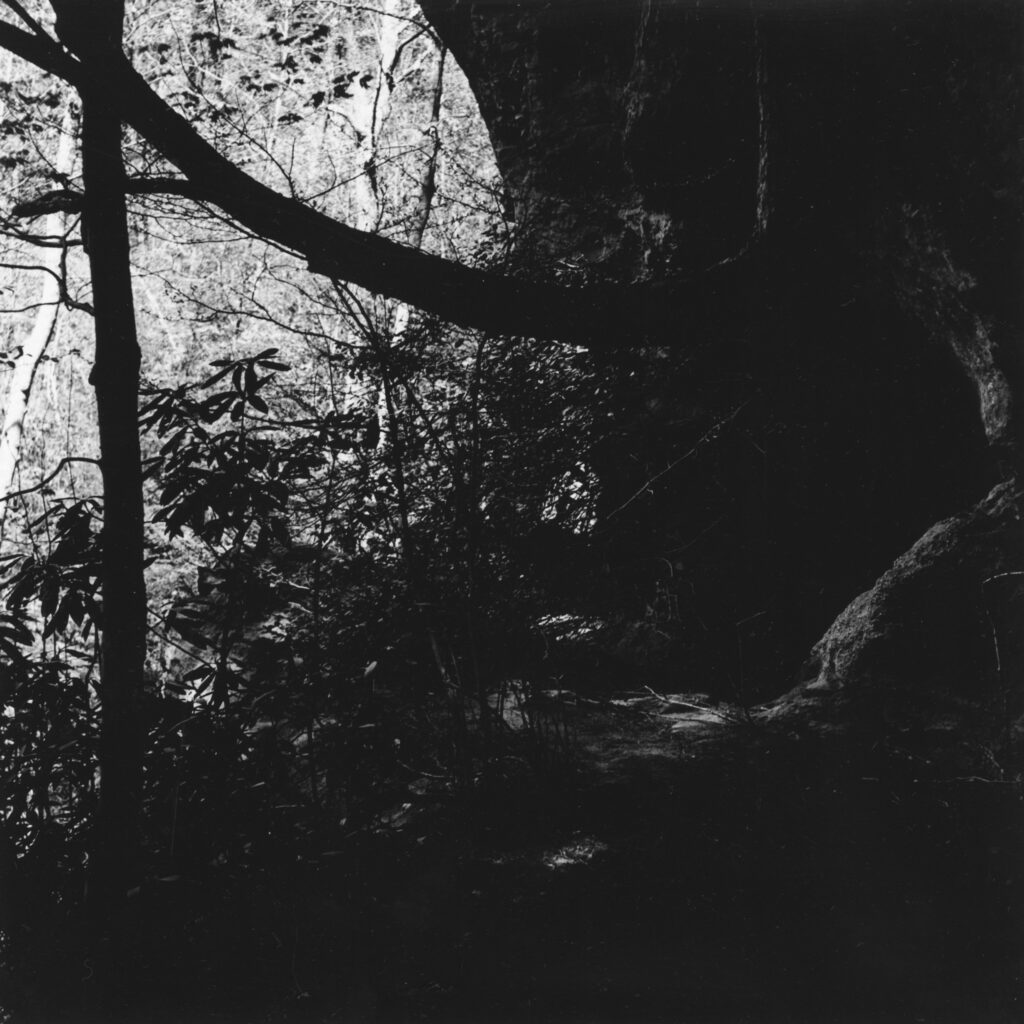

Time after time in this suite of black-and-white prints, Meatyard seeks out the murkiest nooks and crannies of the Gorge. The perspective is not that of the Olympian observer looking down from the mount but, rather, of the hiker on the ground, trekking his way through a primeval landscape, taking in the details one rock, one tree, one stream at a time. He focuses not on what’s on the other side of the river or on the horizon but, rather, on what’s immediately in front of him: trees (standing or fallen), water (standing or swirling), and giant boulders. He’s drawn in particular to cave-like spaces between stone monoliths, in the hollowed-out trunks of trees, and around mounds of crumbling deadfall, pinpricks of light barely piercing the gloom. Large lighted clearings – and occasional glimmerings of the sun itself, just rising or sinking – are merely glimpsed around corners on the trails ahead or through apertures in the rocks, half-screened by hanging leaves or jutting underbrush. Meatyard’s Gorge is a land of shadows and dark enchantment, perhaps cursed.

And so it was. Today we think of the Red River Gorge as part of Kentucky’s most cherished patrimony, a mecca for nature lovers, hikers, rock climbers, and photographers. But in the 1960s and ’70s, it existed under a death sentence. In response to pleas from flood-prone communities along the river, Congress and the Kennedy administration approved a plan to dam the Gorge, which would have destroyed much of its delicate ecosystem and many of its iconic geological features. As part of the opposition to that plan – which included a campaign organized by the Sierra Club and supported by Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas, who joined a protest hike in the Gorge in 1967 – the University Press of Kentucky enlisted Meatyard and writer Wendell Berry to produce a book, published in 1971 as The Unforeseen Wilderness, to sound the alarm. After the protest hike, the Army Corps of Engineers announced that it was postponing plans to build the dam because of planning and budgetary issues. But the Gorge’s future was still in doubt until 1993, when President Bill Clinton signed federal legislation preserving it in its natural state.

Meatyard, then, was photographing a probably doomed national treasure, the product of eons that could be wiped out any minute. “And all along the stream are boulders as big as houses that have broken from the cliffs and tumbled down. . . . Going by them, one thinks of the thousands of miles of water that have flowed past them, and of the generations of Indians and white people that have paddled around them or stopped to fish in their shadows – and one feels their great weight and their silence and endurance,†Berry wrote. “As my knowledge of the place grew, I began to have a sense of the meaning – or the anti-meaning – of its planned destruction, which carried me far beyond the mere principles of conservation and preservation. I began to feel in the presence and substance of its life the complexity and the magnitude of its death.â€

He and Meatyard were engaged in an urgent rescue operation and, on a deeper level, a communion with the very essence of the threatened Gorge. Under that staggering existential burden, many photographers would have knocked out a series of gorgeous, stunning color photographs suited for a Save the Gorge! wall calendar.

But Meatyard could only be Meatyard. A great artist who made his living as an optician while developing an uncompromisingly strange, often surreal body of work (much of it featuring his friends and family members posing in a variety of eerie settings, shot in stygian black and white), he didn’t document the Gorge so much as interpret it. And although there are no people in these photographs, we feel his own distinct presence just behind the camera. We are seeing the Gorge here as only he could, through his eyes, and what he saw was light and dark, openness and enclosure. “In deep shade or in bright sunlight,†he wrote, “there is a tremendous feeling of light and the absence of light – of places to hide or to be fully exposed, bared to all elements.†It’s a telling sentence in which the keyword is feeling. It’s Meatyard’s feeling,as much as anything he sees, that animates these pictures.

Berry recognized, and perhaps anticipated some reactions to, how odd – how unforeseen – the images were. “In some of the pictures this darkness is conventional enough,†he wrote. “It is a shadow thrown by light; we see the lighted tree or stone and we see its cast shadow. In other pictures, the darkness is not shadow at all. It is the darkness that precedes light and somehow includes it; it is the darkness of elemental mystery, the original condition in which light occurs. We are asked to accept the dark as the only condition or way in which we can see the light. And we are asked, then, to see how joyous, subtle, strong, intimate, familiar, and lovely the things of light are.â€

This seems exactly right to me, but Meatyard doesn’t make it easy. The prints in this exhibit present a number of challenges to the viewer. For one thing, they’re all untitled, which makes the identification and discussion of individual images difficult. (This is just what the photographer intended, probably; the images are meant to congregate and accumulate as a unified portfolio, no real stars or standouts allowed – with one exception, about which more later.) The prints are also perversely small, six and three-quarter inches square. To grasp them, you have to stand almost uncomfortably close – in my case, about three feet – and then look harder than you would at almost anything in real life. Meatyard the mastermind surely thought this through, too.

Perhaps most significant to the viewing experience, the photos are printed at a tonal median that’s a couple of notches darker than the images in the book, paperback editions of which are in the gallery. (Kim Spence, curator of the exhibit, confirmed that the set of prints on view, recently acquired by the Speed, were printed by Meatyard himself in 1971.) And the gallery itself is somewhat dimly lit. This deliberate twilight accentuates the prints’ lush, dappled, mystical darkness, but those of us with less than perfect eyesight may find ourselves struggling to pay the close attention the prints insist on.

It would help, probably, to view the exhibit in the order in which Spence has installed it (following the sequence of numbers written by Meatyard on the back of the prints), with the starting point to your left as you enter the gallery. Spence’s – and apparently Meatyard’s – intention is to take us with him on a hike through the Gorge, starting at a point of low elevation and gradually ascending to the top of a ridge, which we glimpse in the images below.

As it happens, I turned right, not left, from the entrance, thereby viewing the show in reverse order, from the highest point to the lowest, down from the ridge into the tenebrous depths toward the river. I walked with Gene Meatyard through stands of old-growth trees, past curtains of leaves and rotting, moss-covered logs, alongside boulders that had stood there thousands or millions of years, flowing water still rubbing away at the rocks, still water reflecting the sky and low-hanging branches.

If the pictures lack the sheer grandeur and technical clarity of Ansel Adams’s work at Yosemite and elsewhere, they compensate with intimacy and a theatrical, almost religious intensity. There’s a profound sense of secrecy here, as if Meatyard has favored you, perhaps grudgingly, with the location of his favorite shrines and hideouts. When it’s there in appreciable amounts, light tends to arrive dramatically, at a steep slant, from offstage – as in this image, in which it skims the frothing stream like the light in the seascapes of Winslow Homer.

Elsewhere it’s distinctly immanent, like the heavenly light that accompanies certain angels in Titian and Veronese, as in these two pictures, each of which feels like a prelude to an annunciation scene.

Best of all, to my mind, are the images of well-lit areas from places of darkness, often peeking from behind massive old trees toward the clearings, or water, just beyond. The perspective is that of a person, or perhaps an animal, in hiding, seeing if the coast is clear. Places to hide or to be fully exposed, bare to all elements. Do we dare to venture out from the cover of our dark, safe cubbyholes into the shimmering, dangerously thrilling light?

Like Orpheus descending into the underworld, I arrived, finally, at the intended beginning of Meatyard’s sequence, a technically experimental image that is unlike all the others.

In this picture – whose effects Meatyard might have created by shaking his camera, or possibly with a double exposure – a path leads upward into the pitch-dark heart of what feels like an explicitly magical, perhaps enchanted forest. The leaves that frame this daunting doorway seem to be shivering uncontrollably, as if bewitched, or excited, or afraid.

Ralph Eugene Meatyard’s The Unforeseen Wilderness is on exhibit at the Speed Art Museum through February 13, 2022.

Top image: Ralph Eugene Meatyard (American, 1967-1971), Untitled from The Unforeseen Wilderness. Gelatin Silver Print.