For African-Americans, travel by car through Lexington and across the USA during the Jim Crow era was a harrowing experience. Some whites, like Lexington’s Joe Duff and his father and brother, welcomed motoring blacks to pull over, rest, refresh and fortify. But the Negro Motorists’ Green Book was a coast-to-coast Godsend. Here is its story.

~ O ~

For much of the nation’s history “the democratic idea of getting out on the open road, finding yourself, heading for distant horizons was only a privilege for white people,†observed Cotton Seiler in Republic of Drivers: A Cultural History of Automobility in America.

For traveling Americans who happened to be black, relying on the kindness of strangers was risk with a capital R.

The Kentucky Civil Rights Act enacted in 1966 prohibits discrimination in public accommodations based on race, color, disability, religion, or national origin. But before ’66 and prior to the 1964 passage of the Federal Civil Rights Act, the tripwires of racial segregation in Lexington and most everywhere else in America were strung taut across the country’s landscape.

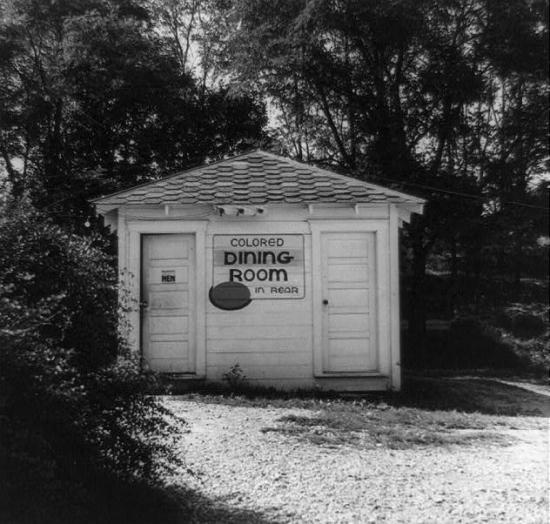

A Washington Post account of the Green Book notes that “Jim Crow laws across the South mandated that restaurants, hotels, pool halls and parks strictly separate whites and blacks. Lynchings kept blacks in fear of mob violence. And there were  thousands of so-called ‘sundown towns,’ including in northern states like Indiana, Illinois, Minnesota and Michigan, which barred blacks after dark, an unofficial rule reinforced by the threat of violence.”

Green Books were sold at Esso service stations, one of the few gas station chains that served African Americans.

At the time, as today’s Baby Boomers were in their formative years, Joe Duff worked for his dad at the family service station on the corner of North Broadway and the newly constructed New Circle Road in Lexington, Kentucky.

The year was 1954. There was a Jerry’s Restaurant across the street. It was for whites only. But the word was circulating among traveling African-Americans that although Duff’s was not an Esso station, Joe’s father was a kind and accommodating man…

For African-Americans increasingly on the move for work, play and family visits, there was a premium on reliable information about places of refuge like Duff’s Service Station in Lexington, Kentucky – knowing where to and where not to make a rest stop, let road-weary and irritable kids out of the car to stretch their legs, find a decent meal, relieve a bursting bladder or refresh with a good night’s sleep.

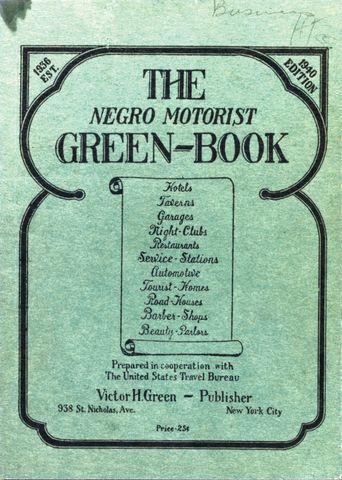

Eighteen years earlier, when Joe Duff was only a toddler, Harlem postal employee and civic leader Victor H. Green had heard one too many accounts of humiliation or violence against blacks traveling across their own nation and was inspired to come up with a credible improvement to often fatefully inaccurate word-of-mouth. Â

The Negro Motorist Green Book organized by state and city places along the nation’s highways where it was safe and welcoming to make a rest or overnight stop.

An introduction in the 1937 edition states: “The idea of ‘The Green Book’ is to compile facts and information connected with motoring, which the Negro Motorist can use and depend upon. We are appealing to the Motorist and Business places for their whole-hearted cooperation to help us in our endeavor, by contributing ideas, suggestions, travel information and articles of interest.†It concludes with the appeal: “Let’s all get together and make motoring better.â€

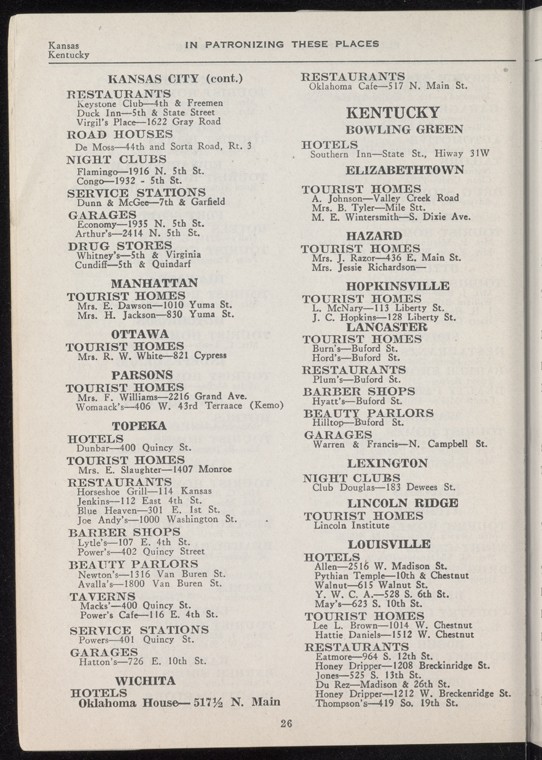

The guide listed cities and places across the country where black motorists were welcome to make a pit stop, check into a motel for the night and have a meal and even in some places like Lexington, enjoy some live music – if not much else.

Soon, those who needed to know about “The Green Book,” had become well aware of it. To much of the rest of America, the “Go Guide” as some readers referred to it, was virtually unknown. The guide was in limited supply with no more than 15,000 printed annually.

And despite Green’s efforts to develop a network of correspondents across the country, there were gaps in the information that left travelers passing through places like Lexington continuing to count on the grapevine. Duff’s service station, for example, never appeared in its pages.

In an interview with NPR’s Neal Conan, the late social activist and civil rights leader Julian Bond recalled how his family relied on Green’s handy guide, by then tucked into the glove boxes of many black-owned vehicles from family cars to musician and baseball team tour buses. “It didn’t matter where you went, Jim Crow was everywhere then, and black travelers needed this badly,” he said.

Washington Post staff writer Courtland Milloy began his own account of a family road trip to the American south by recalling fidgeting in the back seat of his father’s Buick Special for the long drive to Grandma’s house. “The trip started with gaiety in the dark hours of the morning, but as the day wears on it becomes a nightmare. It is 1958. I am almost eight years old, quenching my thirst with bladder-busting cold drinks while riding through the hot, dusty South in an unairconditioned car with my two younger sisters.

Mom is seated attentively next to Dad. He is usually all-powerful and in control, but today, for some reason, he is uptight.”

“The Green Book tried to provide a tool to deal with those situations,” noted Lonnie Bunch, director of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture in an interview with the New York Times. “It also allowed families to protect their children, to help them ward off those horrible points at which they might be thrown out or not permitted to sit somewhere. It was both a defensive and a proactive mechanism.â€

In the parallel universes of a racially segregated society, what had become a staple to some was virtually unknown to many. Green ceased publication in 1964 with passage of the Federal Civil Rights Act and its prohibition of discrimination in public accommodations. In theory, at least, selective “No Vacancy” had been outlawed. That’s not to suggest that bigotry at the lunch counter or registration desk magically disappeared. It takes quite a long time to bring about change of such magnitude. Vestiges of Jim Crow linger in America to this day.

Writers, artists, academics and the just plain curious have been dusting off Victor Green’s publishing legacy and finding within its pages a nuanced context for how things once were and what informs and influences the perspectives of today.

The reason Courtney Milloy’s father and so many like him steeled themselves when behind the wheel is illuminated in Candacy Taylor’s video, “The Negro Motorist Green Book Project: Documenting Sites of Sanctuary. Taylor “travels-while-black” one of America’s most iconic highways, offering an eye-opening reminder of how the road trip, so readily taken for granted by many Americans, was for some fraught with gut-churning dangers of all sorts, mile after mile.

[aesop_video width=”560px” align=”center” src=”youtube” id=”6V0Wxr37N70″ loop=”off” autoplay=”off” controls=”off” viewstart=”off” viewend=”off”]

The guide, now reemerging from history’s shadows, is the focus of The Green Book Chronicles. A film crew led by Calvin Alexander Ramsey, author of the children’s book Ruth and the Green Book, and Becky Wible Searles, an animation professor at the Savannah College of Art and Design’s Atlanta campus have interviewed some of Mr. Green’s relatives and have tracked down families who owned sites mentioned in the books or who relied on it for travel suggestions.

[aesop_video width=”640px” align=”center” src=”vimeo” id=”146908911″ loop=”off” autoplay=”off” controls=”off” viewstart=”off” viewend=”off”]

Ramsey discussed the Green Book in an interview with public radio’s Rick Steves.

The Green Book is a central fixture in the 2015 film 100 Miles to Lordsburg, set in 1961, the fictional story of Jack and Martha, a young, African-American couple, traveling across the country for a new job opportunity in California.

[aesop_video width=”640px” align=”center” src=”vimeo” id=”130567596″ disable_for_mobile=”on” loop=”off” autoplay=”off” controls=”off” viewstart=”off” viewend=”off” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

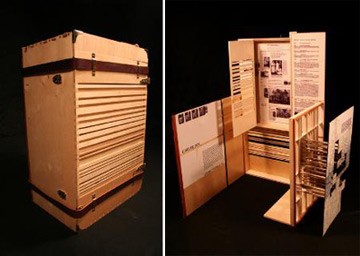

The Dresser Trunk Project, a traveling exhibition organized in 2007 by William Daryl Williams, then an Associate in the University of Virginia School of Architecture and now director of the School of Architecture and Interior Design at the University of Cincinnati, used the Green Book to inform the designs of boxes based on a dresser trunk — the case musicians used to carry their clothing and gear — to tell the stories of African-American artists who traveled along the Southern Crescent train line. The trunks feature stories, photographs, maps, and computer-generated models documenting the clubs, hotels, boarding houses and other places that accommodated black musicians in eleven cities along the Crescent line (currently the Amtrak service connecting New Orleans and New York).

As the pages of the Green Book indicate, the Lexington of the 1950s didn’t offer much at all to the traveling African-American. Still, there were people like the Duff brothers and their dad, letting it be known that some empathy and accommodation could be found on one corner of North Broadway and New Circle Road.

Duff, now 82, has had a lot time since those days to reflect and observe the people who pull up to his gas pumps or bring their vehicles to his service bays…

[aesop_video width=”70%” align=”center” src=”self” hosted=”https://undermain.art/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/16408874_1406037349417431_129139289949732864_n.mp4″ disable_for_mobile=”on” loop=”off” autoplay=”off” controls=”on” viewstart=”off” viewend=”off” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

~O~

UnderMain articles by Tom Martin: