This review published with permission from AEQAI.

“Old age should be a reward, not a punishment,†declares octogenarian Duane Michals. “I must recommend getting older.â€Â 1

Duane Michals, “The Journey of the Spirit After Deathâ€, 15th in sequence, 1971/c. 1971, 27 gelatin silver prints with hand-applied text, photo #15,3 3/8†x 5†(each image), 5†x 7†(each paper), 7†x 9†(framed)

© Duane Michals. Courtesy of DC Moore Gallery, New York

With his vigor, creativity, and capacity for impishness to poke at the sacred cows of the art world, he’s a great advertisement for old age.

As part of FotoFocus, Carl Solway Gallery is presenting three bodies of Michals’ work: “Sequences†from the 1960s and 1970s; “Tintypes†of 2012-2013; and his most recent, “Talking Pictures.†He writes, directs, and acts in what he calls “mini-movies.†They are a logical development from his “Sequences,†where a story is told through a series of silver gelatin prints, some with text written in his own hand. They were described as “evocative mime fables†in the press release for the 1970 “Stories by Duane Michals†exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art. With “Talking Pictures,†Michals has added a soundtrack.

Born February 18, 1932, Michals grew up in McKeesport, Pennsylvania, near Pittsburgh. He’s from a working-class Catholic family of steelworkers and is proud of his blue-collar roots. He remembers them going to work and doing their jobs, and “on Christmas, you have a shot of whiskey and a beer. You know like that. I liked it as a kid, and I still do.â€Â 2

He’s come a long way from McKeesport, which also produced Andy Warhol, and from a home where the only book in the house was “maybe . . . a phone book.â€Â 3 Now his favorite author is the “eternally amazing†Jorge Luis Borges, and the painters he loves are Giorgio De Chirico, René Magritte, and Balthus. He listens to classical music exclusively and is “a huge fan of films like A Room with a View, L’Atalante, or Zero de Conduite by Jean Vigo or Repulsion by Roman Polanski.â€Â 4

That might have been foretold when at 17 with money from his paper route, he bought his first book of poetry–Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass. It was a time when he was struggling with his Catholic upbringing and his homosexuality. 5

As a teen Michals took art classes at the Carnegie Institute and then continued his education at the University of Denver, studying art education to please his parents. After graduating with a B.A. in 1953, Michals spent the next three years in the army. “The army was the worst time in my life. Whatever problems I have to face now, I always tell myself that at least I am not in the army.â€Â 6

Released—or perhaps one could say “liberatedâ€â€”from the service, Michals moved to New York in 1956 to study graphic design at the Parsons School of Design; although he didn’t complete his studies, he did work as a graphic designer.

Michals came to photography by chance, and has no formal training for which has always been grateful since he never had to “unlearn the rules.†He had been designing promotional materials for Time Inc. magazines and in 1958 during the Cold War was given a unique opportunity to go to the USSR. Thinking he should take pictures as souvenirs, he borrowed a camera from a friend who also offered to lend him a light meter. “I refused because that meant I would be expected to take nice, serious pictures!†Instead the friend explained to Michals how to shoot in available light. 7

His decision to use only available light affected his entire career; 90% of the time that’s all he uses. But that has not impeded his career as a professional photographer. He “still managed to do major commercial jobs,†everything from the Paris collections to the 1968 Olympics for the Mexican government to ad campaigns for Elizabeth Arden and Pampers. Michals never eschewed commercial work, as it allowed him to do what he calls “private†work.

When Michals returned to the U.S., he interviewed for a job with “graphic guru†Henry Wolf. He brought a dummy magazine with his portraits of people in Minsk. (He had quickly learned the Russian for “May I take your picture?â€) “When I showed it to him, he said, ‘Who took these pictures?’ and I said I did, and he said that I should be a photographer instead of a graphic designer.â€Â 8

With no formal training—learning as he went along—Michals uses rather basic photo techniques such as underexposing and overexposing, burning and dodging, long and multiple exposures, and sandwiching negatives to create the otherworldly effects seen in his photos. He continues to shoot film (Tri-X) with his 35 mm Canon cameras, using a computer only occasionally.

Michals is celebrated as a photographer, but his preferred sobriquet is “expressionist.†“I’m not a photographer or a writer or a painter or a tap dancer, but rather someone who expresses himself according to his needs,†as he told James A. Cotter in a 2004 story in photoinsider.â€Â 9

Before considering Michals’ “Sequences†and “Talking Pictures,†let’s dispatch with the “Tintypes.†In these he painted vividly colored abstract shapes over 19th-century studio portrait tintypes. The nonobjective additions don’t enhance his dour subjects or even seem related to them. This isn’t the first time for him to try this artistic ploy.

In the 1980s, he painted on his prints and those of others, including Eugène Atget and Henri Cartier-Bresson. Back then he was adding “carefully rendered objects.â€Â 10  But Michals candidly confesses that that work got terrible reviews.â€Â 11 In my view, the more recent effort doesn’t fare much better.

So back to the “Sequences.†In these he uses a series of staged black-and-white photos to tell the story. They are not large by today’s standard; none shown at Solway are larger than 5†x 7â€. “I always said I want my photographs to whisper. Whereas a lot of photographs shout to get attention. Now there are big eight, seven-foot photographs—that’s shouting. A little print you have to come up to—‘Say what? Tell me?’ It’s a whole different experience.â€Â 12

Originally this work wasn’t well received by the photographic community. In a 1968 show in the funky 10th Street Underground Gallery run by Norbert Cleaver, Joel Meyerowitz and Garry Winogrand walked out with Winogrand dismissing the work as “not photography.â€Â 13

And it got worse. Around 1974 Michals began handwriting or printing on the prints like one might in the margins of a book. A teacher at the School of Visual Arts “asked me, very alarmed: ‘What is this thing of writing on photographs?!’ The idea has always been that an image is worth a thousand words, and to have to write something to support or explain an image could only mean that the image had failed . . . But photographs fail all the time and all I did when I started writing in my pictures was to respond to the limitations of the medium. I’ve always thought that photographs don’t tell you enough. They describe very well. But when I write, I am pointing at things that can’t be seen. All this came from the frustration I felt about the silence of the still image.â€14

There are five pieces from Michals’ “Sequences†on view at Solway. I’m conflicted about describing the photos. I don’t want to use a thousand—or even just a few hundred—words to tell what each picture looks like.

So instead of that, here are the eight photos from The Fallen Angel.

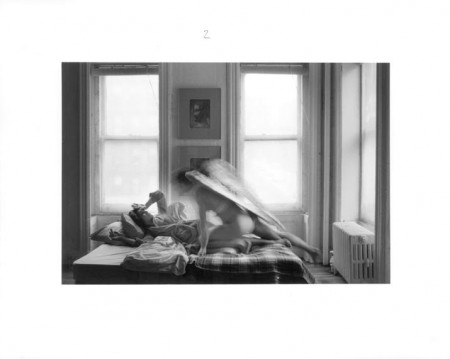

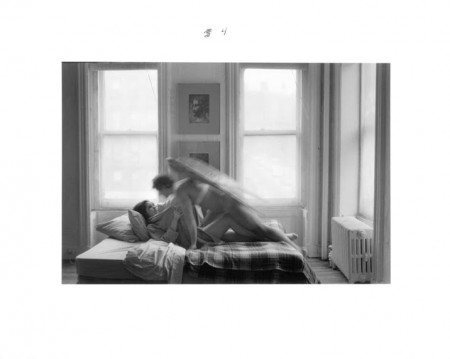

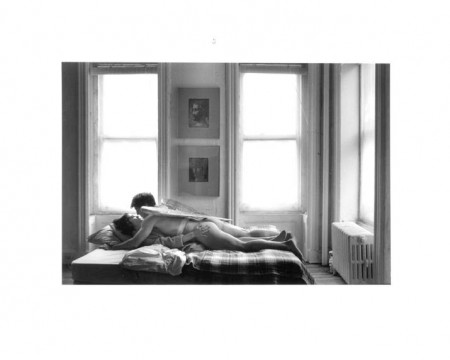

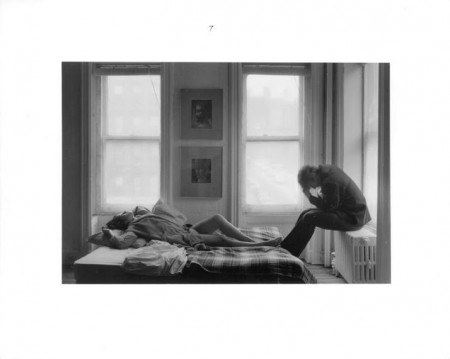

Duane Michals, “The Fallen Angelâ€, 1968/1968, eight gelatin silver prints with hand-applied text, 3.25†x 5†(each image), 5†x 7†(each paper), 7.25†x 9.25†(framed).

© Duane Michals. Courtesy of DC Moore Gallery, New York

Duane Michals, “The Fallen Angelâ€, 1968/1968, eight gelatin silver prints with hand-applied text, 3.25†x 5†(each image), 5†x 7†(each paper), 7.25†x 9.25†(framed).

© Duane Michals. Courtesy of DC Moore Gallery, New York

Duane Michals, “The Fallen Angelâ€, 1968/1968, eight gelatin silver prints with hand-applied text, 3.25†x 5†(each image), 5†x 7†(each paper), 7.25†x 9.25†(framed).

© Duane Michals. Courtesy of DC Moore Gallery, New York

Duane Michals, “The Fallen Angelâ€, 1968/1968, eight gelatin silver prints with hand-applied text, 3.25†x 5†(each image), 5†x 7†(each paper), 7.25†x 9.25†(framed).

© Duane Michals. Courtesy of DC Moore Gallery, New York

Duane Michals, “The Fallen Angelâ€, 1968/1968, eight gelatin silver prints with hand-applied text, 3.25†x 5†(each image), 5†x 7†(each paper), 7.25†x 9.25†(framed).

© Duane Michals. Courtesy of DC Moore Gallery, New York

Duane Michals, “The Fallen Angelâ€, 1968/1968, eight gelatin silver prints with hand-applied text, 3.25†x 5†(each image), 5†x 7†(each paper), 7.25†x 9.25†(framed).

© Duane Michals. Courtesy of DC Moore Gallery, New York

Duane Michals, “The Fallen Angelâ€, 1968/1968, eight gelatin silver prints with hand-applied text, 3.25†x 5†(each image), 5†x 7†(each paper), 7.25†x 9.25†(framed).

© Duane Michals. Courtesy of DC Moore Gallery, New York

Duane Michals, “The Fallen Angelâ€, 1968/1968, eight gelatin silver prints with hand-applied text, 3.25†x 5†(each image), 5†x 7†(each paper), 7.25†x 9.25†(framed).

© Duane Michals. Courtesy of DC Moore Gallery, New York

The story is simple to “read.†A nude angel awakens the girl/woman, but in satisfying his carnal need, loses his divinity. With remorse he clothes himself as he must give up heaven for an earthly existence. The piece is dated 1968, six years before Michals began to add more explanatory and/or confounding text.

As an art historian, I want developments in an artist’s oeuvre to proceed in a neat linear fashion. You can draw a straight line between the “Sequences†and the “Talking Pictures,†but it took 50 or so years to get there. Michals’ mime fables now have a spoken script but address the same issues: life, death, sex, lust, love, grief, fantasy, reality, spirituality, metaphysics.

There are also visual links between the still photos and films. Some of the effects Michals used in his black-and-white photographs, such as double exposures, layering of images, and fades, show up in the color films.

In Tickets to Heaven, Dr. Duanus (Michals) wears crudely lettered sandwich boards advertising tickets to heaven for $5.00 plus tax. Stationed in an alley and using a megaphone, he accosts a man dressed in black. The good doctor is so anxious to make the sale that he knocks off the tax, reduces the price, and offers to throw in the secret grip and the password needed to get past St. Peter: applesauce. Questioned about why “applesauce,†Dr. Duanus lays it out in the simplest terms: “Adam, Eve, snake, apple.†The man, who finds that the scam has a “certain charm,†gives Dr. Duanus a dollar, which he accepts as a down payment. As he passes the huckster, he acquires wings and becomes twinned apparitions on his way to heaven. After the credits, Dr. Duanus reappears, declaring he doesn’t sell tickets to hell, but you can get them from the Republicans down the street.

On the occasion of the 2014 Carnegie retrospective “Storyteller,†Eugene Reznik asked Michals how he felt about his success in his 80s. Michals responded: “I don’t have to prove anything anymore. I’ve defined who I am with the work, so it’s nice. It’s nice and my timing is good. If this had happened when I was 60, or whatever, it would have been quite different. Sometimes it’s bad to peak too soon. That would have been peaking too soon. I’m right on schedule in terms of peaking.â€Â 15

“Duane Michals: Sequences, Tintypes, and Talking Pictures,†Carl Solway Gallery, 424 Findlay St., Cincinnati, OH 45214, 513-621-0069, fax: 513-621-6310, info@solwaygallery.com, www.solwaygallery.com. Hours: Mon.-Fri., 9 am-5 pm; Sat. 12 pm-5 pm. Through January 21, 2017.

FOOTNOTES

1 Jim Provenzano, “The Poet’s Eye,â€Â The Bay Area Reporter Online,â€Â July 5, 2007.

2 Eugene Reznik, “Interview: Duane Michals on 50 Years of Sequences and Staging Photos,â€Â American Photo, November 12, 2014.

3Â Ibid.

4 Lorena Muñoz-Alonso, “Showing the things we cannot see, an interview with Duane Michals,â€Â http://selfselector.co.uk/2013/12/11/showing/-the-things-we-cannot-see-an-interview-with-duane-michals/ Originally published in BuffaloZine, issue 2 [http://buffalozine.com/]

5 James A. Cotter, “Duane Michals†feature story, PhotoInsider, 2004.

6 Muñoz-Alonso.

7Â Ibid.

8Â Ibid.

9Â Cotter.

10 Rebecca Robertson, “Duane Michals: Fighting Against Photography,â€Â ARTnews, summer 2013.

11 Kristine McKenna, “Picture Imperfect: for maverick Duane Michal, a photo is worth far less than a thousand words when the questions are about the very meaning of truth,â€Â Los Angeles Times, March 14, 1993.

12Â Cotter.

13Â Reznik.

14 Muñoz-Alonso.

15Â Reznik.