Copyright is a peculiar thing. Everyone thinks they understand it, but they’re usually wrong. That’s a problem, because copyright is supposed to help authors manage the market for their work and understand when they are infringing on someone else’s work. Unfortunately, it’s hard to know for sure, because courts disagree about when it’s fair for copyright to let authors use a work without permission and when it isn’t.

On October 12, the Supreme Court heard oral argument in Andy Warhol Foundation v. Goldsmith, which could redefine the scope of copyright protection. Lynn Goldsmith photographed Prince. Andy Warhol used Goldsmith’s photo to create 16 paintings. Goldsmith says Warhol infringed the copyright in her photo, the Warhol Foundation says it was fair use, and the Supreme Court has to decide who is right.

It’s a tough case. While Goldsmith owns a copyright in her photo, the fair use doctrine says Warhol could use her photo without her permission, so long as his use was “transformative†and didn’t unfairly compete with Goldsmith’s use. Making it even harder, Goldsmith gave Warhol permission to use her photo to create at least one new work, but what about the other 15?

The Supreme Court heard this case to decide whether Warhol’s use of Goldsmith’s photo was transformative under the fair use doctrine. But answering that question will require the Supreme Court to wrestle with the purpose of copyright and the meaning of art. So let’s dig a little deeper.

What is Copyright?

Copyright is a kind of intellectual property that gives authors certain exclusive rights to use their works of authorship. It was created in 16th century England, in order to regulate the market for books. The Intellectual Property Clause of the Constitution authorized Congress to create copyright, in order to encourage the production of works of authorship. And copyright became a mainstay of our creative economy.

Under the Copyright Act of 1976, copyright automatically protects every “original†work of authorship in any medium. In other words, a work is protected so long as it isn’t a copy of another work and has some unique quality, no matter how trivial. So copyright protects books, songs, movies, and paintings. But it also protects just about every Facebook status update, Instagram post, or tweet, whether or not the author even realizes it.

Among other things, copyright gives authors the exclusive right to reproduce copies of their work and to create derivative works based on their work. You generally can’t copy a copyrighted work without the author’s permission. Of course, authors can give people permission to copy their work. And they can also sell people licenses.

What is “Fair Use�

But there are many exceptions to copyright. One of the most important exceptions is the fair use doctrine, which provides that certain uses of a copyrighted work are non-infringing, so you don’t have to ask for permission. The Copyright Act states that the use of a copyrighted work for the purpose of “criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, or research†is not infringing. It also provides four factors courts should consider when deciding whether a particular use of a work is fair:

- The purpose and character of the use;

- The nature of the copyrighted work;

- The amount and substantiality of the work used; and

- The effect of the use on the market for the copyrighted work.

Essentially, the fair use doctrine says you can use a copyrighted work without permission if you are using it in a different way than the copyright owner.

When courts ask whether a use of a copyrighted work is fair, they typically ask whether the use is “transformative†and whether it competes with the copyright owner’s use of the work. For example, in Campbell v. Acuff-Rose (1994), the Supreme Court concluded that 2 Live Crew’s use of Roy Orbison’s song “Oh, Pretty Woman†to create the parody song “Pretty Woman†was fair, because it transformed Orbison’s song and didn’t compete with it.

Now, 2 Live Crew copied a lot of Orbison’s song. But it didn’t matter. The Supreme Court observed that parody requires a lot of copying, otherwise no one will know it’s a parody. But parody is highly transformative because it makes a work mean the opposite of the original. Apparently, copying is fine, so long as the genre requires it.

Orbison also argued that 2 Live Crew competed with his right to license a rap parody, but the Supreme Court disagreed. It observed that Orbison had no intention of licensing a rap parody, so the competition was purely hypothetical. But it also questioned whether parodies ever need a license. After all, parody is a kind of criticism or commentary, which the Copyright Act says is fair use.

The Photographer and the Philosopher

As Justice Marshall memorably observed, it’s the duty of the Supreme Court to say what the law is. But it says what the law is by deciding particular cases, so the facts always matter, or at least they’re supposed to matter. What actually happened in Warhol v. Goldsmith?

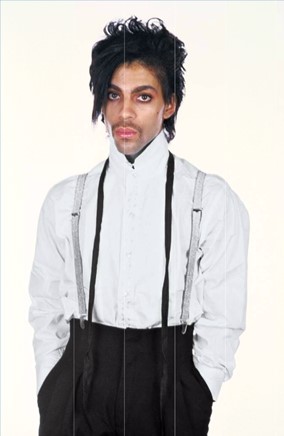

The story begins in 1981 when Lynn Goldsmith did a photoshoot for Newsweek, in which she created many portraits of Prince. While Newsweek didn’t publish any of those portraits, Goldsmith licensed them to other publishers. In 1984, Vanity Fair paid Lynn Goldsmith $400 for a license to use one of her photos as an “artist reference†for an illustration.

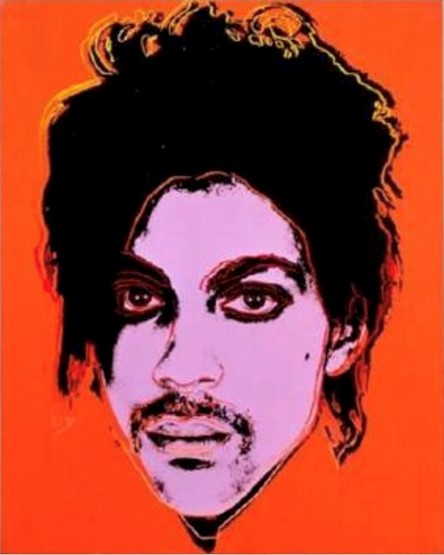

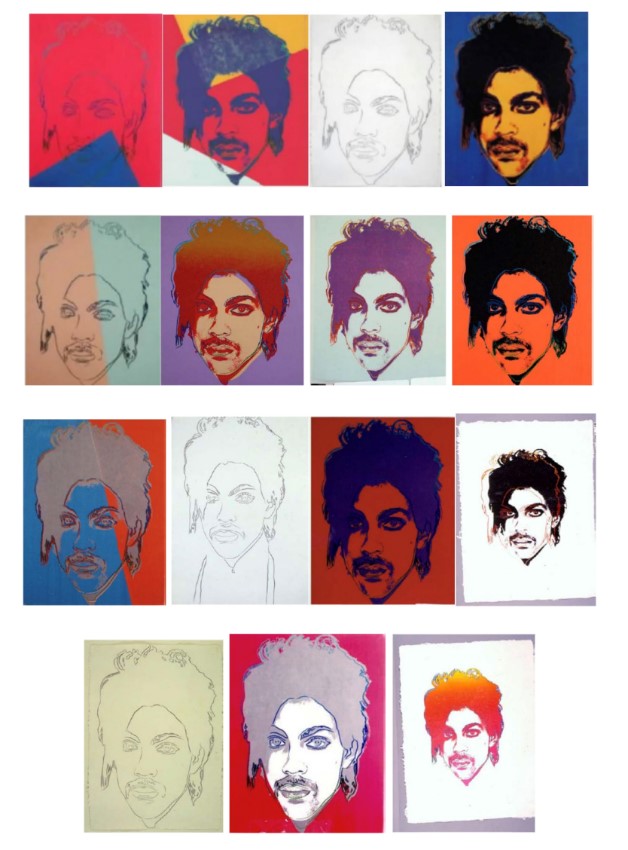

Unbeknownst to Goldsmith, the illustration was created by Andy Warhol, who used Goldsmith’s photograph as the basis for 16 paintings, one of which was published in Vanity Fair, illustrating an article about Prince. As usual, Warhol heavily cropped the photo, using only Prince’s face, and made a silkscreen, which he used to create the paintings.

When Prince died in 2016, Vanity Fair paid the Warhol Foundation $10,250 to reprint Warhol’s illustration on the cover of an issue commemorating his death. Goldsmith objected that reprinting the photograph wasn’t covered by the original license, and threatened to sue Condé Nast, the publisher of Vanity Fair, for copyright infringement.

When the Andy Warhol Foundation learned of Goldsmith’s threat, it filed a declaratory judgment action in the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York, asking the court to find that Warhol’s use of Goldsmith’s photograph to create the Prince Series was a non-infringing fair use. Goldsmith responded by countersuing the Andy Warhol Foundation for copyright infringement.

The district court granted summary judgment to the Andy Warhol Foundation, holding that Warhol’s use of Goldsmith’s photograph was fair use. But the Second Circuit reversed, holding that Warhol’s use of the photograph was not fair use, because it was insufficiently transformative, among other things. The Supreme Court decided to review the case and heard oral argument on October 12, 2022. It will probably decide the case sometime in June 2023.

Is Contemporary Art Prohibited?

Superficially, Warhol v. Goldsmith looks straightforward: Are Warhol’s paintings a fair use of Goldsmith’s photograph? But copyright questions don’t get any harder. The fair use doctrine isn’t really a legal doctrine in the traditional sense, but a way of characterizing a policy question: When should copyright prevent people from using works for expressive purposes? After all, in Eldred v. Ashcroft (2003), the Supreme Court held that copyright is consistent with the First Amendment only because of “built-in free speech safeguards†like fair use.

Often, copyright infringement is obvious. If someone creates a copyrighted work of authorship and you sell copies of their work without their permission, you’re an infringer, easy. Fair use only comes up in difficult cases. What does it mean to “transform†a work and when does a derivative work unfairly compete with the original?

Goldsmith argues Warhol improperly copied her photo 15 times without permission. He had a license to make one painting, but should have gotten a license for the others as well. What’s more, Goldsmith was entitled to a licensing fee and a credit when Vanity Fair reprinted Warhol’s illustration. Warhol responds that his use of Goldsmith’s photo was transformative, because he gave it new meaning, and his paintings didn’t compete with Goldsmith’s photos at all. How do we know? Because Vanity Fair wanted a Warhol illustration, not a Goldsmith photo.

What will happen if Goldsmith wins? According to her, not much. It’ll just mean that artists who use copyrighted photos in their works will have to pay licensing fees to the photographers. But that is an absurd misreading of copyright law, which gives authors the exclusive right to create derivative works. If Warhol’s paintings infringe Goldsmith’s photos, then Goldsmith can ask the court to prohibit their display and request their destruction. And the same would be true of any artist who uses copyrighted photos in their work, unless they transform those photos more extensively than Warhol.

How will the Supreme Court decide? Based on the oral argument, it’s hard to say. The questions and answers were all over the place. While Chief Justice Roberts and Justice Kagan seemed skeptical of Goldsmith’s position, other justices seemed more sympathetic. However, odds are the Supreme Court will find for Warhol and reverse the Second Circuit. After all, it rarely takes cases like this one in order to affirm the lower court. The question is why will the Supreme Court reverse, and how will it articulate the standard for determining whether the use of a copyrighted work is fair.

Chances are the Supreme Court will try to explain when the use of a copyrighted work is transformative and when it isn’t. Good luck. Lower courts have been trying to formulate a test for transformativeness for 30 years now, and the best they can do is, “I know it when I see it.†The oral argument didn’t suggest the Supreme Court is likely to do any better. Maybe a better rule is “don’t fix what ain’t broke.†Artists have been using existing images to create new works since time immemorial. How is Warhol any different?

Embed for November 3, 2022 – Brian Frye_CopyrightListen here to Tom Martin’s interview with Brian Frye about the SCOTUS case on WEKU’s Eastern Standard.