John Hunt Morgan, “Thunderbolt of the Confederacyâ€, is safe in his construction cocoon. Protected from debris and damage during the much-anticipated renovation of Lexington’s historic courthouse, the statue of Morgan was erected by the United Daughters of the Confederacy in 1911, during the dark century of continued subjugation in the South of freed slaves and their descendants following the Civil War. The Morgan statue will greet visitors to the courthouse’s main entrance upon completion of the renovation.

The Morgan memorial, and its companion statue in the courthouse plaza, erected in 1887, of John C. Breckinridge, Vice-President of the United States, slave owner, defender of secession, Confederate general, and the last Secretary of War of the Confederate States of America, create an heroic tableau that some have called “historyâ€.

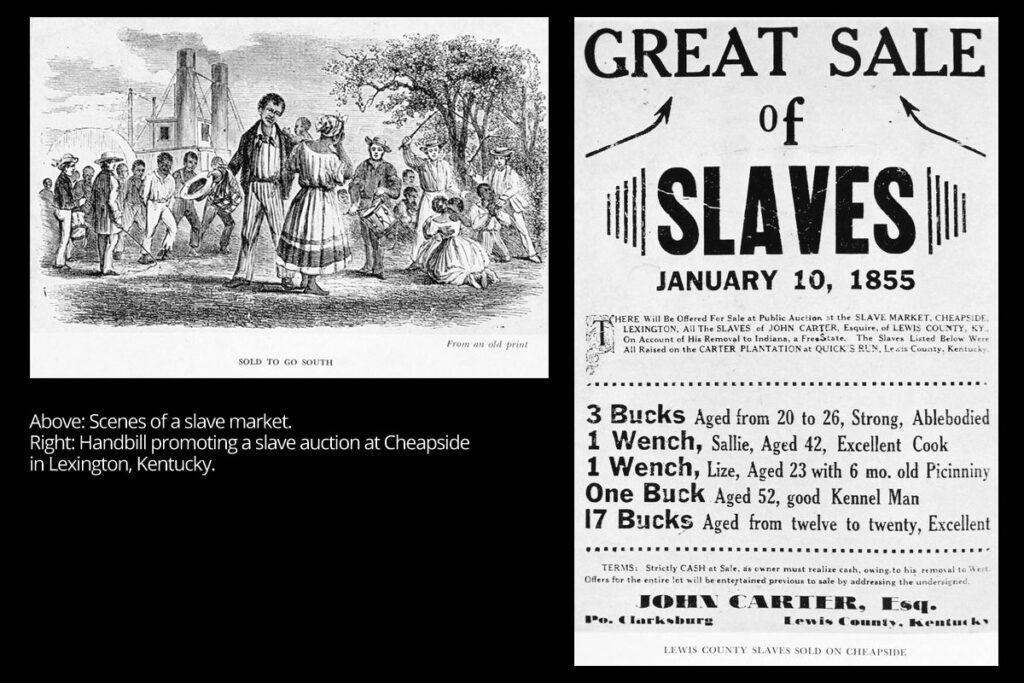

The statues were erected in the public square, on a block which was, in the first-half of the nineteenth century, the site of major slave auctions, and marked in recent times by a small, lonely plaque.

At the end of a summer riven by blood, outrage, fear, and protest, is it still important to talk about some statues?

The conversation about Lexington’s courthouse statues, begun after the massacre at “Mother” Emanuel A.M.E. Church in Charleston, South Carolina, continued last fall. Mayor Jim Gray charged the Urban County Arts Review Board (UCARB) to make recommendations concerning the future of the statues, highlighting the need to reflect “shared valuesâ€, diversity, and inclusiveness.

The Board studied the issues exhaustively, heard testimony from experts and the public, and encouraged submission of letters of opinion from the general public. They received many more letters in support of retaining the statues in their locations in the courthouse square. Nevertheless, in November the Board recommended that the statues of Morgan and Breckinridge be moved from the courthouse block to other publicly accessible, appropriate places.

At the meeting where this and other recommendations were made, the UCARB members looked on incredulously as, at the eleventh hour, city officials informed them that removal of the statues might very well jeopardize the federal historic tax credits that were a vital part of the financing of the courthouse renovation. The extensiveness of discussions with federal historic preservation officials concerning this issue has never been publicly disclosed.

After the November UCARB meeting the public conversation about the statues went into a deep sleep.

In mid-February of this year, Chris Corcoran, an advisor to Mayor Gray, announced that the Mayor had decided to keep the statues in place, telling the Arts Review Board:

“The mayor’s intent is to keep those statutes where they are and provide more context,†(italics are mine) Corcoran said. “We are not pursuing moving the statues.â€

Conversation over.

They say that history is written by the victors, and all across the South in the decades after the Civil War the believers in “The Lost Cause†retained the symbols of the Confederacy and valorized its heroes. It was a victory after defeat and a message of warning to those who would try to upend the renewed and revived architecture of domination and subjugation. The new heroes, inheritors of the mantle, were men in white robes, police officers with dogs and billy clubs, and governors standing in schoolhouse doors.

So what would be more context for our statues, presiding in place in our public square?

Perhaps this:

The statues of Morgan and Breckinridge stand as testament that history can be warped and defiled. That a gauzy cover can be applied to it to encourage a recasting of the true history of a vile cause. That a history of a place, our public square, the site of untold suffering in the decades before the Civil War, can be nearly erased. These statues are not “history”, they only mark the attempts by people in history to rework history. Mark this; the statues were erected not just to memorialize heroes of “The Lost Cause†but to serve as a warning to those who would attempt to impede that revision of history and challenge its contemporary malevolent regime.

Not enough more context?

The men valorized by these statues were inhabited by an evil and degrading ideology. An ideology of racial superiority in service of a system that required centuries of enslavement of other human beings. So, Africans stolen from their homelands and their descendants, were subjected to the most cruel and inhumane conditions, treated and tortured as beast of burdens, and bought and sold as property of others on this very spot. These slaves were instrumental in building the early America.

The fever of this racist malignant ideology and system was only stanched by a most bloody and wrenching civil war. It still remains to be fully extinguished. Slavery in the United States takes its place amongst the most horrific and prolonged injustices and acts in humanity’s known history. It is the cause for which Morgan fought and died and Breckinridge avidly served. This is the true history to be remembered in this place amongst these statues.

We whitewash or forget this truth at our peril.

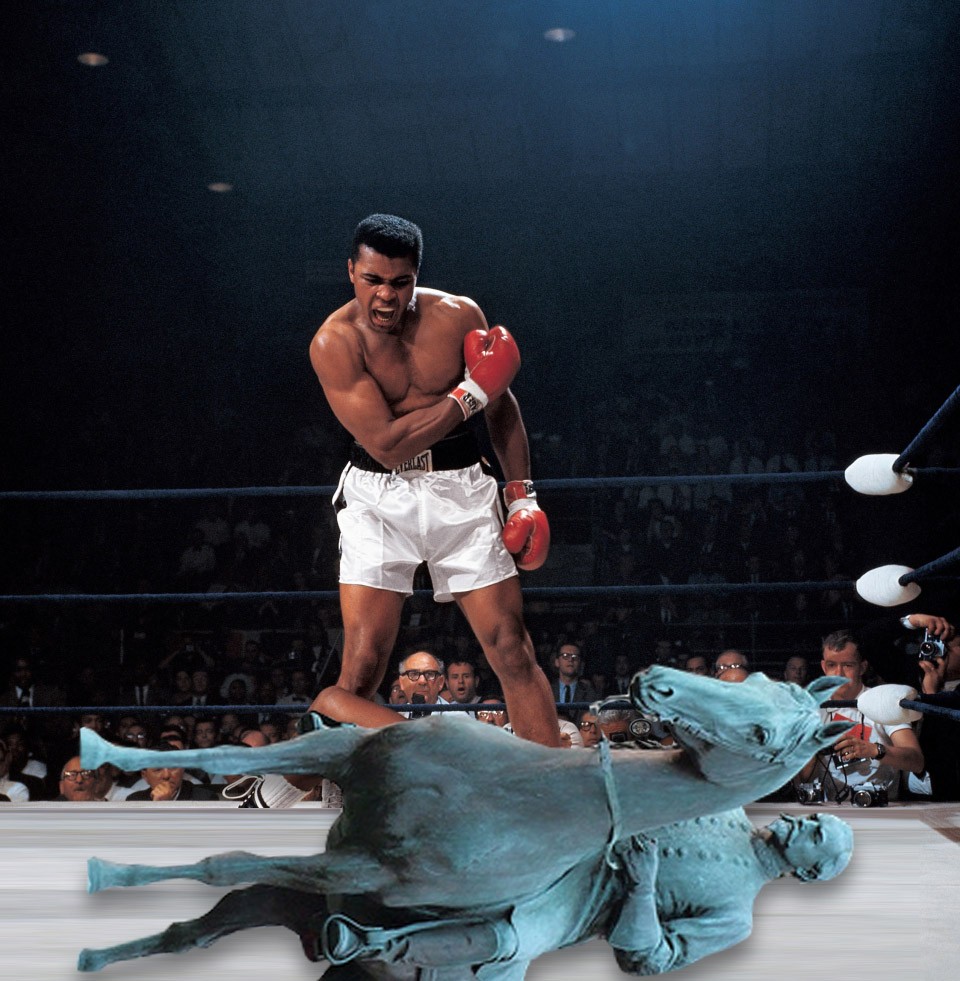

But perhaps the most appropriate more context, would be this image, suggested in a conversation with UK Art Museum Director, Stuart Horodner, and projected large throughout the courthouse plaza:

For another response to the courthouse statues see Tom Martin’s UnderMain piece about Kurt Godhe and Kremena Todorova’s latest community engagement art project, Unlearn Fear+Hate.

Slave auction announcement image courtesy of University of Kentucky

Ali-Morgan image courtesy of Chris RosenthalÂ