The problem with binary thinking is that by reducing the world to a simple either/or proposition, we neglect to see a third option. In most cases, our experiences, identities, and worldviews cannot be simply categorized as one thing or another; more frequently these entities are mutually inclusive, existing on a continuum or in a dialectic, rather than a dichotomy. This third option—wherein two things not only coexist but are interrelated—is at the heart of Melissa Vandenberg’s work as an artist. Vandenberg’s practice brings together elements of right and left; historical and contemporary; North and South; masculinity and femininity; and ephemerality and permanence in such a way that highlights how these polarities reveal a third, interconnected option. Working in a wide array of media and subjects throughout her career, Vandenberg explores the borders of our thinking and makes us aware of the processes therein.

Melissa Vandenberg’s interest in the interconnection of various seemingly polar entities is rooted in her own identity as an artist. When asked if she considers herself a Southern artist, for instance, Vandenberg opts for a more ambiguous identification than offered in a simple yes or no. Rather, she demonstrates both an interest in embracing the moniker and a reluctance to truly identify as such, given her status as a transplant. Born in Michigan and having migrated slowly more southward through her education and work—completing her MFA at Southern Illinois University, Carbondale and having worked in Indiana and Tennessee before settling into a faculty position at Eastern Kentucky University in 2009—Vandenberg is acutely aware of her status as a Northern native living in Appalachia. At the same time, having spent a decade in Eastern Kentucky, she recognizes the influence of the region on her identity as an artist, readily embracing the environment as a consideration in her work. Hers is thus a perspective of both insider and outsider, one who knows the area from having lived here, but whose native identity is tied up somewhere else.

Similarly, Vandenberg’s work cannot be defined by a particular medium. Her practice involves sculpture, installation, performance, drawing, and photography, and she readily embraces working in all of these forms. Not identifying with a particular medium, however, has made her feel alienated in many American art contexts until relatively recently. As she notes: “I’ll use video and photography [and I’ll] also draw. I’ll do performance. I’ll do installation. And I didn’t feel like I had a niche or home for a long time and I think that [lack of a particular medium] was frowned upon, not just from commercial venues, but just in general, as if I was indecisive. And I’m like ‘no, I’m equally serious about all these things and it should be my concept that’s leading the material choices anyhow. […] Isn’t that where we went after the 60s?’” Vandenberg’s identity as an artist could be defined as “mixed media” or “intermedia”, but she will also readily admit that there are clear connections between these seemingly disparate entities of her own practice. In particular, she regularly embraces fiber as the basis for her work, making large scale, soft sculpture from sewn textiles, using sewing machines in her performances, and even using cotton rag paper as the basis for her drawings. As such, her practice similarly defies the binary that an artist must either be understood as a medium-specific or multimedia practitioner, offering a third option comprised of both.

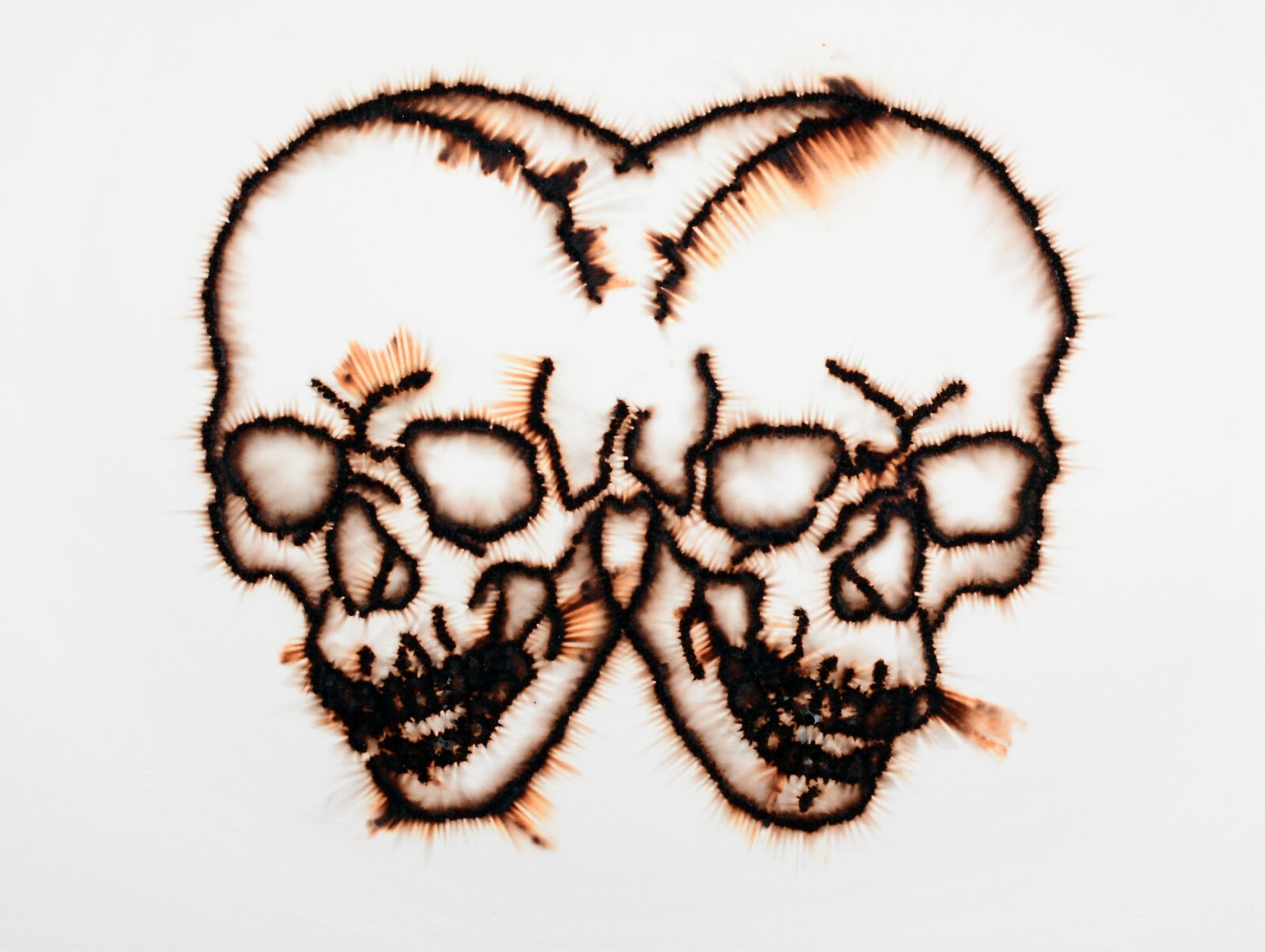

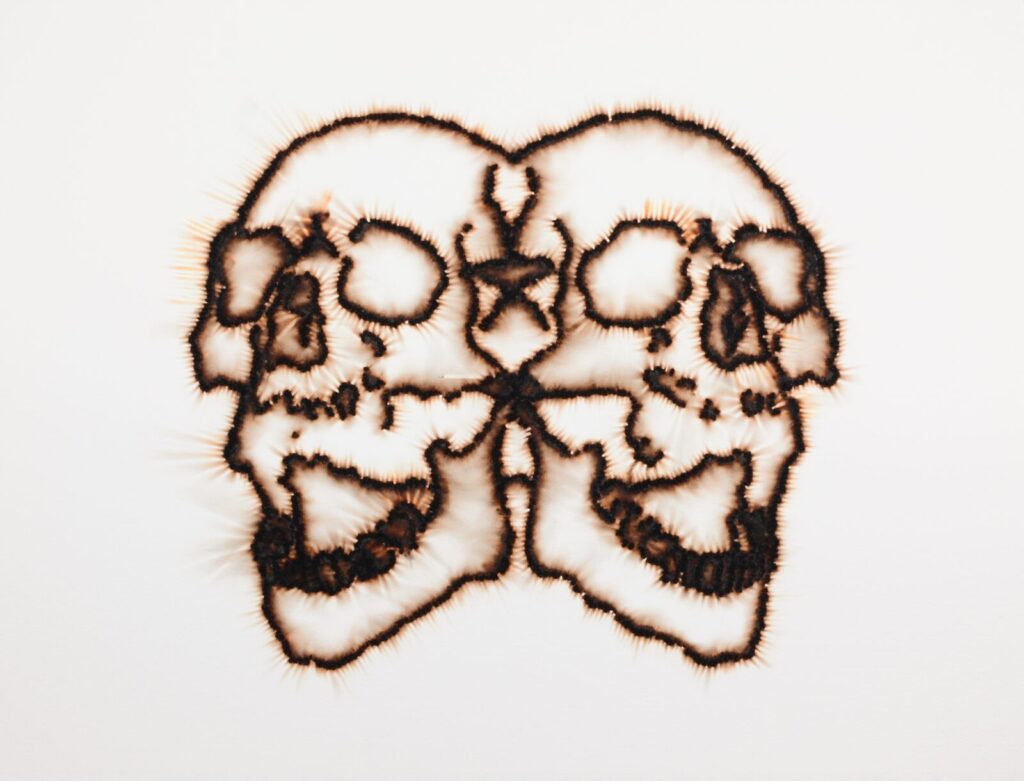

Looking at her work, it is readily apparent how her practice similarly engages with the dialectic between seemingly binary entities. In her most recent body of work, Vandenberg has created a series of triptychs comprised of “burn drawings,” which she has created by burning matches directly into Arches paper. In particular, her set of skull drawings, entitled Doublespeak, Double-Talk, and Red Vanitas, examine how two entities that are apparently diametrically opposed can actually merge to become one in the same, or an inclusive third. In each of these three works, two skulls look out in opposing directions, their metaphorical gazes fixed on something the other clearly cannot see. At the same time, their cranial structures overlap, merging them into a singular entity, one that is equally dependent on the form of the other in order to exist.

For Vandenberg, this overlap and the dichotomy it undermines function to critique the extreme prevalence of binary thinking within our contemporary culture, both locally and world-wide. She notes: “I’ve been using conjoined metaphors for a while. I think [of the motif as reflecting] this political climate, the general divisiveness, [and] realizing, you know, the supposed right and left—and this is even a global situation, not just here.” Vandenberg’s skulls do look left and right and, yet, the two are ultimately part of the same entity. These works, therefore, call attention to the fact that the ideological and, even, the physical delineation of left and right are interdependent parts of a single whole. Just as a physical object cannot have solely a left or a right side—as there will always be a boundary on the opposite side—neither can a political ideology exist solely in one camp or another; the limitations of the polar opposite are, therefore, essential to create a cogent definition. By conjoining the two entities as such, Vandenberg highlights the fact these distinctions in our culture are truly interdependent.

Vandenberg’s skulls not only ruminate on ideological dichotomies, but they also undermine the duality between past and present, or the (art) historical and the contemporary. For Vandenberg, this series of burn drawings offers an opportunity to consider the legacy of historical motifs and objects. The use of the skull makes a clear reference to the Dutch still life tradition of the “vanitas,” wherein the still life painter would include a material reference to death among the sumptuous painted display. At the same time, both materially and temporally, Vandenberg’s skulls convey a particular sense of the present. As previously noted, the conjoined nature of them calls attention to our contemporary historical conditions. Furthermore, the materiality of the burn drawing itself has a clearly instantaneous quality to it, one that is created with a meticulous precision in terms of timing, which imbues the work with a clear sense of the now. Combining the historical references with this notion of the present, Vandenberg’s work thus calls attention to the falseness of the dichotomy between past and present, revealing the continuum upon which both entities exist.

Vandenberg’s interest in combining seemingly dichotomous entities is not solely a recent venture. For years now, she has explored the limits of these distinctions throughout her practice, both literally and metaphorically. Geographic delineations, in particular, have been a consistent theme throughout much of her work. Just as her own identity as an artist has been shaped by time spent in both the North and the South, she has used her practice to explore the differentiation between these two regions. In 2010, for instance, she carried out her Middleland Project, wherein she spent several weeks traveling along the boundary between the Northern and Southern United States. The project offered a reimagining of American borders, highlighting the various identities that emerge within and across these two regions. As Vandenberg notes: “[t]hese are not your usual border states; semantically they are an amalgamation of the Heartland, the Midwest, the Bible Belt, just south of the Rust Belt and flanking the Mason Dixon Divide. They provide a rich yet fractured history as ideologies are constantly challenged from the surrounding North and South.”[1]

Vandenberg documented her journey in a variety of media, including photographs and a blog that she maintained during her travels. The resulting project is a series of images and texts illuminating the complicated and multifaceted expressions of regional identities that exist along the borderlands, demonstrating the ways in which people North of the divide share values and lived experiences with those South of it, while also noting the moments in which real differences are apparent. In exploring the line between North and South through this project, Vandenberg highlights the existence of a third possible identity, one that transcends and transgresses the division of the border itself.

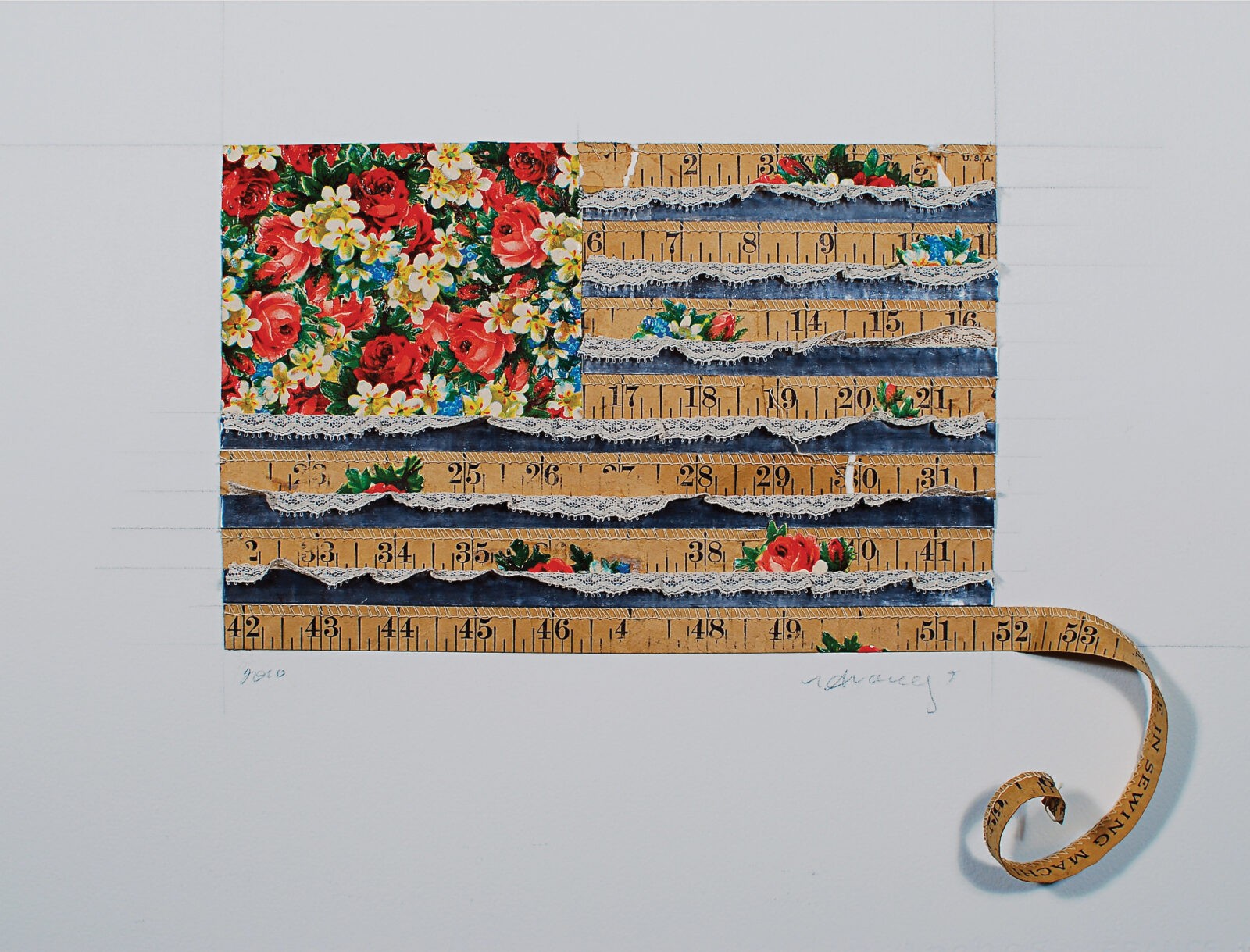

Her practice not only considers the interwoven nature of geographic boundaries, but also the interrelatedness that characterizes gender binaries. In particular, her sculpture practice has, for years, juxtaposed elements of masculinity and femininity in a way that calls attention to the limits of these two categories. For instance, in her work Monument, Vandenberg combines the masculinity associated with militarism and patriotic service with the femininity of textile work. In this work, Vandenberg constructs a portable, stuffed obelisk out of the fabric of several deconstructed flags. As such, the work calls attention to the particularly masculine traits of patriotic duty and military sacrifice, alluding to the cemetery memorials that mark the graves of countless American soldiers. (While women have, for centuries, served in military roles, the vast majority of service members killed in the line of duty have been men, due largely to the exclusion of women from combat roles until 2016.)

At the same time, Vandenberg incorporates clearly feminine signifiers into her monument through her choice of materials. Sewing, and textile work more generally, is unquestionably feminine, having been one of the primary forms of craft practices that have characterized women’s art for centuries. Broadly speaking, within flag culture, women’s roles have historically been as makers, using our talents with needle and thread to construct symbolic objects, the most iconic example of such being the Revolutionary War seamstress Betsy Ross. Therefore, by incorporating this textile tradition and rendering her monument visibly soft—a characteristic often attributed to women both in physical form and in temperament— Vandenberg complicates the masculinity associated with the obelisk and the militaristic culture it represents.

In bringing together two sides of this binary, Vandenberg again demonstrates how these notions are, indeed, interconnected. The softness of the stuffed fabric combined with the rigidity of the form of the obelisk proposes a reconceptualization of gender wherein the dichotomy between manliness and womanhood is replaced with a more nuanced and dialectic understanding. Because this form is neither completely masculine nor completely feminine, it posits the existence of some hybridity between the two, thus illustrating that the binary is false and that some combination thereof is likely more common.

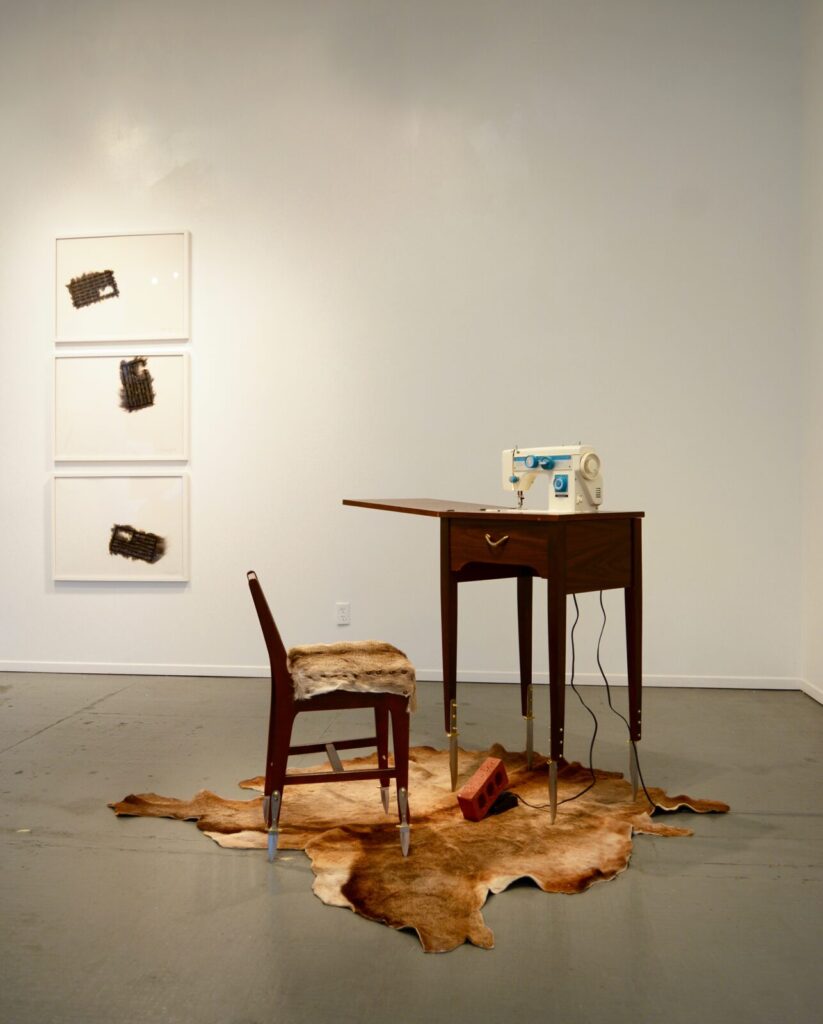

In her practice, Vandenberg has challenged the apparent duality of gender on multiple occasions, including in more recent work like the piece Homewrecker. In this work, Vandenberg has constructed a sewing station precariously propped up on a variety of knives, all of which sit on a flattened deer hide, while a brick placed on the pedal keeps the machine running. Like with her monument, the sewing machine itself is a synecdoche for womanhood. The metaphorical reference to womanhood is made more apparent through the fact that it is a “homemaker” brand machine, calling to mind one of the central elements of women’s labor and identities for centuries. At the same time, the knives—bowie knives along the base of the machine and throwing knives extending down the legs of the chair—coupled with the skinned deer hide allude to hunting, one of the most traditional and archetypal roles for men going back to hunter/gatherer societies.

And yet even with the clear gender distinctions that are apparent on the surface of the work, the piece highlights the complicated and intertwined nature of gender. For instance, as Vandenberg notes, the deer hide itself can be understood as a feminine form, particularly as deer have held “a lot of symbolism in every religion, […]usually related to purity and fertility.” The masculinity of hunting is therefore undercut by the femininity associated with the deer in various spiritual practices. Through this juxtaposition, Vandenberg continues to complicate binary gender distinctions in her work, highlighting the capacity of objects and individuals to perform both roles simultaneously.

The gender dichotomy is only one of the multiple binaries challenged in Homewrecker; the piece also ruminates of the duality of ephemerality and permanence. In particular, the physical construction of the work is both temporary and enduring. On the one hand, the assembled items that comprise the sculpture—the sewing machine, the seat, the knives, the hide, and the brick—are all sturdy and long-lasting items. On the other hand, the permanence of these objects is undercut by the dynamic and mechanical nature of the work. By strategically placing a brick on the foot pedal of the sewing machine, Vandenberg has created an object that will continue to vibrate so long as it is on display, ultimately causing the knives to cut into the deer hide and thus destroy the work as it once existed. In creating a work that appears static but is, in fact, always changing, Vandenberg highlights the interrelatedness between the ephemeral and the permanent. That the deer hide appears permanently whole but is actually being altered moment by moment illustrates how things may appear eternal, but they are never quite that. At the same time, that the fleeting and momentary vibrations of the sewing machine are causing the knives to damage the hide instant by instant also illustrates the impact of ephemerality on more permanent conditions.

Throughout her career, Melissa Vandenberg has used her practice to critically examine multifaceted and complex issues, layering meaning into the various elements of each work to create a totality rife with bold statements and nuanced assertions. Despite working in a wide variety of media, there are clearly remarkable through lines that create wholeness out of what could be understood as disunity. Similarly, though her work addresses a considerable number of disparate ideas, the distinctions among them frequently function to unite her practice and the issues she addresses. Her work challenges us to think in more complicated ways, abandoning reductive logic that seeks to delineate the world in binary forms, offering us instead a way to see a possible interconnected third.

[1]Melissa Vandenberg to Middleland: Artwork and commentary focused on the landscape flanking the Mason-Dixon Divide. , February 26, 2010, http://middleland2010.blogspot.com/?view=magazine.