The job of a parent is to keep your child safe. These efforts start before birth and continue until – and in many cases, through – adulthood. Parents grow preoccupied with the safety and the long-term implications of every single choice we make, from the way we lay our children down in their cribs to the schools we enroll them in. And yet, despite all this effort, the safety of our children is never guaranteed. Violence, disease, natural disasters, and accidents encircle us and impact our lives in sometimes seemingly random ways, revealing how little control we actually have in ensuring the safety of our loved ones.

This loss of control is at the heart of Becky Alley’s most recent body of work, a series she calls Hope Chest. In these works, Alley ruminates on what we can give to our children in an uncertain world, focusing on the resilience and resourcefulness needed to continue to adapt to the myriad and often overlapping tragedies that inform our human experience. Drawing on the idea of a “hope chest†– a box given to a daughter by her mother, grandmothers, and aunts that are filled with heirlooms and resources to prepare them for eventual marriage – Alley has fashioned a variety of new legacy objects, ones that can be used for survival in extreme circumstances, instead of within the confines of the home.

In particular, Alley has fashioned the objects typically found within a hope chest – books, quilts, bed linens, and other small knick-knacks – out of unconventional materials, specifically items typically used for survival in extreme circumstances. For instance, in one work, Heirlooms, Alley has draped a blanket that she weaved herself from paracord and deconstructed emergency blankets over a pair of cedar sawhorses. Within the folds of the blanket rest several soft, white forms, which are objects from around Alley’s home that she has covered in white felt. In another, Alley has constructed a set of quilts using tarps and emergency blankets, which she has strung up to approximate a makeshift shelter, held fast by sandbags made from bedsheets. And in yet another work, Alley has woven a net out of utility twine, which hangs off a book-like loom over another set of bedsheet sandbags. Throughout the series, Alley has used utility materials – things often found prepackaged in hardware or surplus stores and intended for use while braving the wild – to create seemingly domestic legacy objects, like quilts and blankets to be passed on to prepare a child for adulthood, as occurs in the case of a Hope Chest. In so doing, Alley has transformed the concept of the hope chest by changing the nature of the objects within it and transforming how they are displayed.

These items, while utilitarian, are also marked with love and care, just as the domestic goods that often filled hope chests in generations past; Alley has hand-crafted each one, repurposing surplus materials, and thus transforming them from mass-produced survival gear into individuated objects in a gesture that is not unlike parenting itself. She has lavished care and attention on each item, transforming the basic material into a particular and singular form, one that is adaptable and capable to withstand a considerable amount of adversity, much as we attempt to do in raising our own offspring.

I had the opportunity to talk with Becky Alley at T+D Gallery in Berea in mid-February 2022, where this series was on display. During this visit, we were able to discuss this body of work as it relates to some of her previous projects, specifically the series of war memorials that she has been making for several years. In those works, Alley has created visual references to account for the loss of life in various wars and military conflicts throughout history. For Alley, “those ended up being […] about creating space for things that I felt like collectively we weren’t really giving space for.†In particular, Alley cites the discourse of 9/11 and the moments that followed as shaping how she thought about her work. She notes “what I was responding to in that work [was] trying to have another conversation maybe about patriotism and war and making space for things like empathy […] and just the and just giving the notion of mourning or even acknowledging the loss of people, that you might not even know.â€

And for years, Alley has created works that ruminated on the value of a single life lost in conflict. Throughout her Memorials series, she has created monuments to the dead that unsettle a lot of our expectations and assumptions about memorializing conflict. Alley notes “And with the war Memorials, a lot of that was a response to how we perform war and visualize war in terms of memorials and monuments and how that’s all tied up in gender and what we think of as strong. […] Many war memorials are kind of big and metal or stone and […] they’re large. But then at the same time, they can become almost forgettable, which is kind of the irony of their size and presence. […T]hey can make a big impact initially, but then they become easy to kind of forget about once they’re integrated into a landscape.â€

Alley wanted to create memorials that stuck in memory and that used a different visual language than the monuments that decorate our public sites. She notes: “part of what I was doing with those was intentionally making work that was very delicate.†Alley’s Memorials are unquestionably delicate, ranging from 160,000 individually burnt matches in her piece Burn – which memorializes the death of civilians in the War in Iraq since 2003 – to the 4503 leaves dangling from clothespins and string that memorialize the deaths of US Soldiers in that same conflict in her piece Fallen. In creating war memorials from precarious – and in the case of the leaves, ephemeral – materials, Alley’s monuments remind us of the preciousness and finitude of life.

Moreover, Alley’s Memorials are impactful not only because they are delicate, but also because they seek to quantify numbers of human lives that are almost unquantifiable. Throughout the entire series, Alley accumulates individual items – plastic flags, pins, threaded needles, book pages coated in soap, and, of course, leaves and matches – on a scale of thousands, each one meant to represent a single human being. Alley places each one in a particular arrangement to illuminate the totality of the cost of human violence.

Such a gesture requires the utmost care and Alley’s memorials, as a result, require meticulous and dedicated upkeep. As she notes: “I had that piece with all the burnt matches. I had the wall with all the many, many plastic white flags. And none of them were glued together. None of them were permanently attached. So every time I installed it, I had to put in the labor to put it up and take it down. And even when it was up, you know, there was always the possibility that some matches might fall[…] And so it was this built-in kind of tending to that the pieces required.†The care she offers each symbolic life is, in many ways, a reflection of the care that goes into each life that was lost. Each person who has perished in conflict is a product of the care of someone, and Alley materializes the nature of that care by creating a memorial that is neither forgettable nor permanent, but requires the same sort of attention and effort as nourishing human life does.

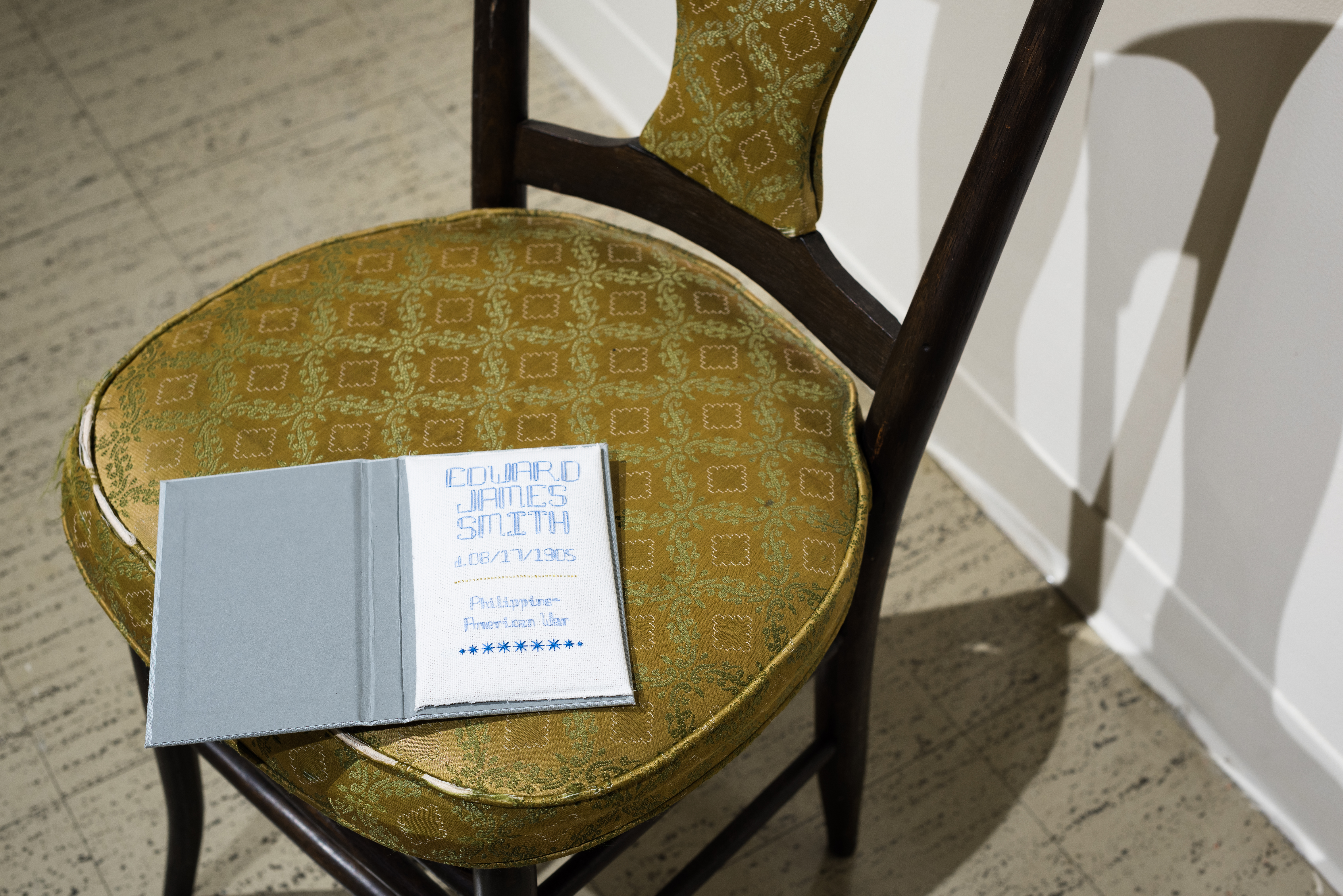

In this way, Alley’s Memorials involve a similar investment in caring about the life of another as parenting often does. And she brings her own identity as a parent into those works as well. In one piece, Epitaphs for Edwards (2016), Alley constructed 220 books, each with a hand-stitched epitaph for a soldier named Edward (or a variation thereof) who had died in armed conflict since the US’s founding. The choice of the name Edward reflected Alley’s own identity as a mother, since that is her own son’s name, and in creating the work, she sought to visualize “the perspective of a grieving mother.†Moreover, by giving names to the dead, a gesture that is distinct from the abstract representations of the loss of life in her other work, and providing an epitaph for each individual, Alley reminds the viewers that the soldiers lost in conflict had once been someone’s child. That the epitaphs are hand-stitched – by Alley and 41 volunteers, many of whom were mothers themselves – adds an additional layer of care and attention to the memorialization of each individual, a further enactment of maternal grief.

For Alley, the number of books is also particularly significant, since that is the number of years that the US was involved in military action between 1776 and 2016 (the year she completed the work), a total that amounts to approximately 93% of our history. Alley took to researching the histories of these conflicts and identifying soldiers named Edward who had died each year of a conflict and creating an individual monument to each one, while also making “a visual timeline of all the years we’ve been engaged in some sort of military conflict.†In so doing, Alley creates an opportunity to ruminate on, as she puts it, “our identity as a nation and what it says about who we are if we’ve almost always been at war or in some conflict.†Alley thus creates a work that not only memorializes the considerable and continual death during violent conflicts, but also commemorates the grief of those whose lives were altered by the loss of their loved ones, by highlighting the care that symbolically surrounded each individual Edward.

While Alley has been ruminating on human tragedy through her war memorials for years, her Hope Chest series considers the legacy of tragedy from a very different angle, one that is focused on the present and even looks to the future. For Alley, this shift in her work is largely due to the changes in her life due to the COVID-19 pandemic. As she notes, many of the pieces in Hope Chest: “were done on my kitchen table right at the beginning of COVID. I didn’t have a studio. I was at home. And so they were small, just sort of little experiments, just thinking about sort of imagining them and these other materials. And then the longer we were at home, I ended up kind of carving out a studio space for myself.†Alley began by working on quilts, creating quilt patterns out of different materials, including a series of “utility tape drawings†from patterns she had found in a book she acquired at the start of the pandemic.

For Alley, as for most of us, the pandemic meant a shift in where and how to work, and it also meant a shift in who was present for that work. While Alley has worked collaboratively before, and whereas quilts have traditionally been made by communities of women, the pandemic forced Alley’s quilting process to be a solitary endeavor. Yet the solitude of her creative work was punctuated by the (omni)presence of her children during the pandemic. She notes: “I mean my kids were sort of running around and it was fun how excited they were at the colors I was using […] I have plenty of squares that I was learning on that didn’t quite turn out straight or whatever. And they really liked playing with them and they just liked the gold and the silver and all the colors and, you know, so that there was that kind of exchange and dynamic, but otherwise [it was a] whole solitary process.â€

Alley kept that sense of play alive in the final works themselves. For instance, in hanging her Quilts like a tent, Alley enjoys the fact that her kids instinctively go to hide and play in the structure like it is a fort and hopes other children may have the same instinct. And Alley has made these items to withstand not only disaster, but also play. She notes: “these are not fragile things. They can be played around with and if the pile gets moved or knocked over you just put it back up because nothing is delicate about it.†The robustness of the materials in Hope Chest thus stands in contrast to the delicacy of her Memorials, a distinction that further illustrates the difference between a series about loss and one about survival.

That Alley was in pandemic isolation with her children when making these works is mirrored in the ideas behind the series. Being a parent during the pandemic has often meant confronting the difficult reality of our own vulnerability and that of our children. Keeping our children safe has often meant tremendous sacrifice and strain on their parts and on ours, and the outcomes of those sacrifices are far from guaranteed. Moreover, the longstanding question for all pandemic parents is the long-term impact of these two years on our children’s lives. What will they carry with them? What detriments have befallen them because of the loss of school or social interactions? What are the long-term impacts of illness should they become sick? What will they inherit from us as a result of this cataclysmic global event? In creating a series of works that consider both survival and inheritance, Alley has made visible the tensions that are felt by all parents and have only become more acute the longer we have been in this crisis.

And yet, Alley’s works are not hopeless or nihilistic in the face of these issues. Rather, she has sought to transform the resiliency of survival into something beautiful to behold, something we should aspire to. As Alley notes: “that idea of resiliency almost became more important to me as a parent, rather than even being able to prepare them for anything in particular, because I don’t know what the world is going to be. I don’t know what they will face. […] It’s sort of shifted a lot of what I was thinking […]Or maybe it just helped me articulate a little bit about how to prioritize parenting and the idea of raising them to sort of be resilient, adaptable, you know, […to] expect or look for color and play while also being prepared for a disaster at the same time.†Indeed, if there’s anything that we should put in our hope chest for our children it is the ability to be so resilient and adaptable that we can make quilts out of tarps and turn those tarps into tents; that we can transform emergency blankets and utility tape into beautiful objects that can not only help us survive tragedy but allow us to thrive despite adversity.

Top image: A detail shot of Becky Alley’s Quilts​, 2021, tarps, emergency blankets, bedsheets, paracord, sand. The photo shows a grouping of white sand bags sitting on a gallery floor in front of colorful quilts. Image courtesy of the artist.