I. TIME

It is June 23, 2022, at 2:15pm CST. I am in St. Louis, Missouri, for a performance at The Luminary. Since I am not in Chicago, this fact shortens my distance from the work of Sanford Biggers at the Speed Museum in Louisville, Kentucky, from 301 miles to 260 miles. The 260 miles between me and the work are folded in time and space through the glitchy interwebs of Zoom. To me, navigating a tactile memory, this feels insufficient. Time has failed me. I want to parallel the work. I to thread and eye to quilt. But alas, the show closes in three days and I won’t be able to make it in person. Luckily, with unflinching clarity and charisma, Sanford Biggers and Speed Museum Curator Scott Erbes animate the exhibition for me. I am a child in this way, gathered around a 14.2-inch screen – in awe of the story of Sanford Biggers: Codeswitch.

II. PLACE

Here, in St. Louis, the weather is surprisingly thick, sultry, and dewy. I am slowly realizing that I have anchored my emotional body in the Midwest and at the same time, somatically, my body house knew that I was in the South. This distinction caused me friction. Is this place the “Midwest†or the “Southâ€??? I wonder, then turn to search the web. My search box knows that “Is Misseri considered a southern stare?†means “Is Missouri considered a southern state?†Behold, it is. Sometimes your brain plays tricks on you. Sometimes it tells you that St. Louis is a place that lives on the borders, on the edges and peripheries. That it doesn’t belong to the South or to the Midwest, maybe not even to “Misseri” or Missouri. That maybe it’s just a Free City. It has a liminality of its own that suspends any regional categorization other than birthing the iconic group St. Lunatics, whose top song on Spotify is coincidentally entitled “Midwest Swing†from their Free City album. During a conversation with a friend, in preparation for this talk, we contemplated how the same geographical confusion lingers about the state of Kentucky. To me, Kentucky is exuberantly a southern state. To others, it’s a little less clear, which to some feels like an intentional rewriting. I am excited to walk through this bewilderment with Sanford and Scott. I wonder what is gained and lost when refashioning and shifting the narrative of placehood? What stories are lost or hidden? What emerges from this ultimate rewriting? What is the role of “the artist†in this place?

III. SPACE

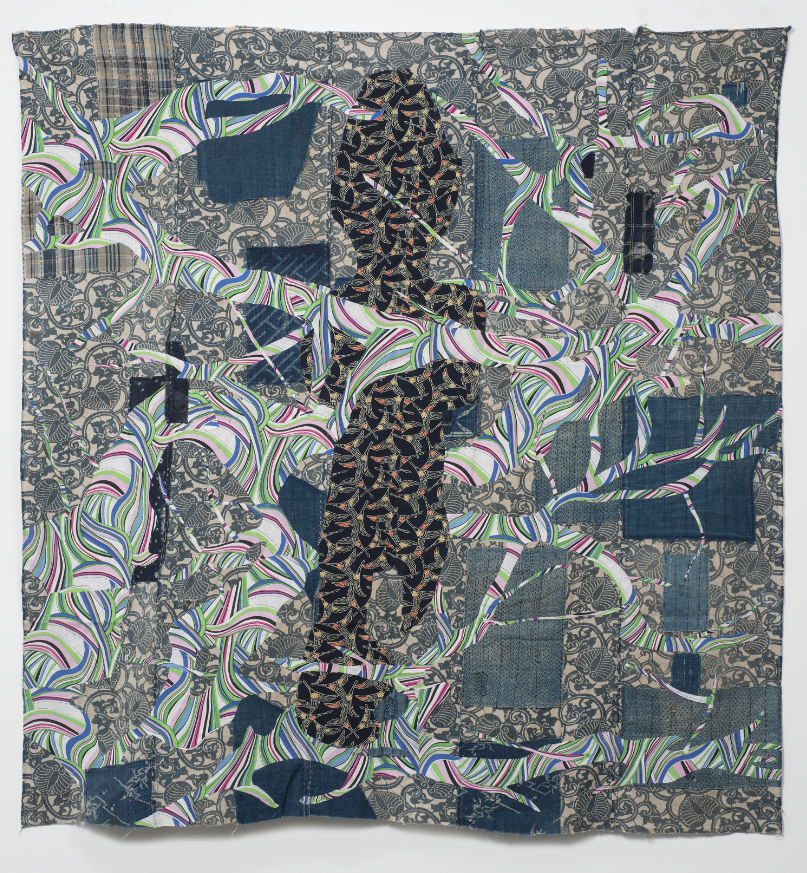

Sanford Biggers has orbited giant stars from an early age just as the Little Fox did in our solar system. Samella Lewis, John Biggers, and Noah Purifoy, to name a few of those giants. I am gripped by the ways that mentorship can act as an axis to uncoordinated efforts. How can stars collide and illuminate a winding path that provides an axis, an anchor, a compass? In uncoordinated efforts of my own, I am enthralled in the work of Terry Adkins (1953–2014), specifically the ghostly X-ray images of memory vessels from Adkins’ personal collection. Memory vessels are funerary objects found in the South on the graves of African Americans throughout the mid‑20th century. These small stoneware vessels were adorned with fragments – broken china, glass shards, seashells, beads – and items beloved by the departed. Adkins collected hundreds of memory vessels from the mid-1990s until his death; the X-ray images came during his tenure as Professor of Fine Arts at the University of Pennsylvania. The images of these spirited vessels carry a haunting that feels as astronomical and daunting as the galaxies look in our solar system – an unexplainable vastness. The vessels meet at the crux of material culture and ancestral communication. I immediately think of Sanford Biggers’ The Talk made from antique quilt, assorted textiles, tar, and glitter, a galaxy of its own. I learn that Terry Adkins mentored Sanford Biggers during his time at the University of Pennsylvania. In this way, giant stars of mine collide.

Visual artist Sanford Biggers, Curator Scott Erbes, and I talk about the proverbial rupturing of story-making and storytelling. Hybrid in nature and in spirit, we meander around the traditions of quilt making and its thread through other cultural formations and mediums. There is a metabolization of aesthetics and labyrinthian relationships between the modes of communication that Biggers ushers us through in Codeswitch. As the exhibition’s title implies, the works presented are united by their de/coded attributions of communing the possibilities at the intersections of material culture and visual articulation. We begin our conversation with the cyclicality of trajectory.

isra rene: As a quilt maker, tell us about your process when making. Is there a beginning and end? Where does it unfold?

Sanford Biggers: I do appreciate you calling me a quilt maker, but I don’t actually make the quilts that I work on. I work on quilts that are found, thrown away, or donated. Really, any way I can get my hand on them. I typically try to focus on pre-1900 quilts because I just like the quality. The thread quality, the stitch quality, color saturation, or lack thereof, and the wear that I usually find on those types of quilts. But to directly answer your question, it’s really sort of a nonlinear approach because I’m subject to what materials I get. I definitely come into the use of the quilt through conceptual art and thinking about the readymade. But also the sort of inherent politics in American quilts specifically on the different areas they come from, and the groups and individual women we assume our quilts are made by. Although there are men that sometimes contribute or even make their own quilts, of course, I just like the fact that it’s changed from its inception from the actual making of the quilt. Once they’ve been used and have that patina of age that gives it another quality. And then when they’re on their way to being thrown out, or people are looking for a place to give them because nobody wants to throw away a quilt, I take that all into consideration when I’m working with the material. I respond to that. I respond to the wear and tear. I respond to the patterns, or sometimes I totally veer off from the pattern in a way to try to make it more focal or make it more secondary. So, you know, each approach is just different.

ir: Engaging with your quilts alongside the Quilts from the Eleanor Bingham Miller Collection feels like an active momentum of time travel. What conversation is happening between your cryptic configurative quilts with the more traditional quilts that you would find on your grandmother’s bed?

SB: Well, not to go too far back in history, but when I started taking art seriously, I actually got into it from doing graffiti in Los Angeles as a tween. I think part of what I’m doing, even with the found materials I work with now, is riding the attention line between vandalism and beautification, or modification, or however you want to phrase it. So, with respect to the other quilts that are there, of course, they supply a foundation. They provide quilting works in different languages, certain patterns, have their own histories, and so on. It almost works as a codex, to then go and see my work where obviously, there’s been interventions put on that are a different set of codes, different sets of patterns, different motifs. The idea is to flesh out a larger visual language that transcends, you know, history. I’m interpreting a certain degree of code from those quilts and then putting on another layer that will probably be read by other future decoders of palimpsest of American symbology. So I think there’s a relationship between the two of them that way, that the ones downstairs are sort of the precursor, or even though some of them were probably made after or the same time as some of the quilts I’m working with, but that there was another intervention that’s happened that is more contemporary.

ir: And for me, another layer in your intervention is the geographical location. The place where your materials come from and how that is generative to the work. I mean, the work lives in Kentucky right now but comes from all over. How does it feel to have your work in Kentucky right now? Kentucky, the most midwestern southern state. (laughs)

SB: Scott, do you wanna –

Scott Erbes: You know, my research has historically been with “anti-quilt” traditions in the United States, particularly here in Kentucky. Kentucky, aside from known documented quilt makers who tended to sometimes be idiosyncratic, what you see both in quilt making happening in Kentucky and the 19th century into the 20th is the same thing you see with other material culture here. Kentucky was the first American West. And because of that, it was really one of the first sites where in a very compressed time period in the early 19th century – well, up until about 1850-1860 – where you have all these people coming from different places within the United States whether that’s South, Mid-Atlantic, New England, and also from abroad, and of course both free and enslaved people of color within the state as well. So the material culture here tends to just be sort of a mashup of a lot of different things colliding together. And you see that in historic quilt making traditions here, too.

SB: I think a theme that I’ve been interested in, in all of my various projects, whether it be the quilter’s cultures or any of the work I’ve been doing over the last 20 years, is the idea of syncretism. Oftentimes, it’s either cross-cultural or cross-historical but essentially finding points of similarity from seemingly disparate sources over time or location. I think that goes to what Scott’s saying about Kentucky sort of having that type of mix of cultures and influences. I brought up syncretism to say that over the last few years I started thinking syncretism in terms of patchwork, and patchwork being a very good metaphor for exactly what Scott just mentioned, and my approach to materials, and symbolic references, and to what you were alluding to – me traveling and living in various places, and living in various countries and cultures, and bringing vestiges of that back into the work. We’re talking about quilts, but my mind right now is thinking about kimonos. I use a lot of kimono material in the quilts, but I lived in Japan for three years and I spent a lot of time at kimono shops. And you know, a friend of mine’s family had a kimono shop. Even in those kimonos, you’re seeing a bunch of syncretism from various different groups throughout Asia. Putting those into the American quilt to me is not necessarily a cultural leap, but it’s more of a material synchronicity. I like the idea of the patchwork being also a version of a melting pot that is sort of tangible in material needs.

SE: That’s a great point. Just in American quilt making in general, you see that happening. Old-order Amish quilting in Pennsylvania was a 20th-century response by the old-order Amish to other more mainstream “quilt making” practices. You see that happening, you know, say their distinct Mennonite quilting traditions as well that have their sort of own palettes, their own patterns that then were influenced by and also influenced other groups depending on the region in which they’re working. I think that speaks to the American patchwork quilting as a pretty unique visual tradition here. I mean, it happens in other places certainly. The way the material, the use of pattern, it just lends itself to almost a linguistic sort of practice. It has that sort of built into it, you know, where it is visual languages that evolve and change depending on time and place.

ir: The title of the show is Codeswitch, which is a method of communication with a long history of colonialism. There are stories and histories imbued throughout the work in its material culture and sometimes literally. What stories are gathered from the work in this show?

SB: It’s very hard because when I started doing this series, there was a lot of frontloading in the sense that there was research and thinking about how to make this work speak visually, but also conceptually and also historically. I think part of that was developing a language. But once I started to get a little bit more acclimated to that language, I sort of wanted the interpretations to be open source. My dream is for two or three different people to look at the same quilt and all pull something different but share what they see and expand all of our understandings of what’s happening in the work, you know. I try not to be overly prescriptive with specific messages. Over time, some symbols of mine have come to mean certain things for me, but I also have very specifically used some references that are merely archetypal. You will find versions of them in so many different regions of the world that you start to realize that the reason you’re connecting with it is not because of its specificity, but sort of how it’s more visceral – like you already understand the nomenclature without having to be versed in that length.

ir: They’re crafting their own stories in their minds and sort of following a thread….

SB: (laughs) Nice pun. Part of that though is because I think artworks start to live when they interact with the viewer. And if I shut down their ability to experience it on their own, then I’m ultimately doing a disservice to the work.

ir: I’m left wondering about the utility of the object. Something happens in material culture when a piece of fabric or textile is hung on a wall. What was the process of collaboration in displaying the work in this show?

SE: In terms of this exhibition, that was collaborative. For an exhibition like this, that’s organized by colleagues and the artist, we want to make sure we’re creating an environment where they can achieve what they want within our space. We’re more the executors than the originators. Museums have – in the era of COVID – gotten very good at design and layout and enacting layouts using WhatsApp, FaceTime, Zoom. So, that’s sort of how this worked, too. Sanford, correct me if I’m wrong – I think we probably had the largest space of the three venues for the exhibition.

SB: Yes. Bronx (The Bronx Museum of the Arts) was big, but the layout was different. Yours definitely felt a bit more roomy. You had more rooms and more areas, too. So, yes, I think ultimately yours was probably the largest.

SE: I think that gave us some flexibility, honestly, particularly in terms of the video pieces, which always take up real estate.

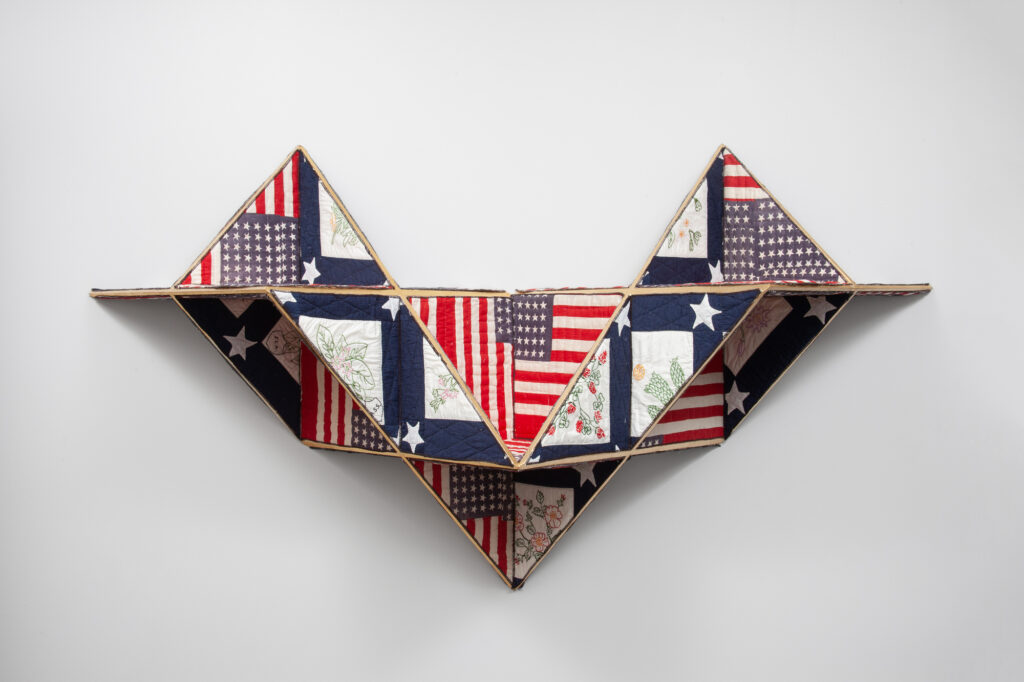

SB: I think part of my interest in working with quilts started from an interest in museological display. A lot of the sculptures that I’ve been doing are riffing by using power objects from various primordial cultures throughout the world. I’ve always been fascinated about what happens when these practical objects, these objects that were used for ceremonial, ritual, or worship, or for private purposes are then disconnected from that and then put into the museum and how the museum deals with it. And over the years, seeing how museums have found ways to try to bring in more of the original environment that those were placed in, specifically when you see objects from pre-Columbian societies, and early Asian, and African cultures, and so on. I think that Codeswitch is interesting because what you’re alluding to also is that these quilts are used. They wrapped themselves around bodies. They provide comfort. They’re on beds. And when they’re on the wall, how do they operate? And for me, I like to think that they still are performative objects. They still can work as sculptures. They also bear witness to the mundane household performances; the nightly rituals; the keeping babies, and elderly, and people warm; and all of that. That is somehow also embedded in the work. And I think the name Codeswitch comes from that, is that the objects themselves aren’t solely paintings. They’re not solely drawings. They’re not solely costumes, or utilitarian objects, or sculptures, but there’s some patchwork involved.

ir: Riffing as a site of decolonial communication. I think of Jazz and Graffiti as having a similar architectonic intersection. How do these things scaffold in your mind?

SB: Well, you know, I’m a child of rap and first-stream hip-hop. So, I was doing graffiti. The first moment I saw artistic graffiti murals in Wild Style, the film that my dad took me and my two other tween buddies to see because we couldn’t get in without an adult. And you know, we watched this thing and we left and had our markers in our books, trying to copy everything we saw. All that to ultimately sneaking out of the house and doing graffiti murals throughout LA. There is something about the vitality of that – it’s punk rock. There’s a very fine line between early rap and punk rock. It’s sort of that same youth culture vibe basically.

All through my formal education as an artist, there was always a desire to make sure that that rawness stayed in the work even though they didn’t talk about it at those schools, and they looked down on it at those schools at that point. I knew that there was something vital about that and that’s why I still use fat markers, and oil sticks, and spray paint even on the quilts that are there at Speed right now. There’s also the musical and compositional elements of rap and hip-hop, cutting and pasting, sampling, and so on. Once again, it’s patchwork. To me, it references that as sort of a cultural zeitgeist and a way of working that the quilt can do. What the quilt supplies that I miss sometimes from rap and hip-hop is that deep, deep history, that deep American history. Not just of the South, not just of Black folks, but of Americans, and I think the quilts do that. I mentioned that tension before. I remember the first time I ever did actually a public conversation about the first quilts I did in Pennsylvania. And the entire group that showed up were all quilters, hardcore quilters, no contemporary artists, no conceptual artists. Quilters. And I was attacked. (Scott and isra laugh)

SB: I was laughing at the same time, like, you guys came to the wrong show. What I’m doing is something different, but I’m glad I’m getting this energy. At the same time, it’s because there is that sense that I was desecrating these objects. To use the hip-hop metaphors, not many people were thinking about that song from 1956. There was B side on a one-hit wonder until it was resampled by Pusha T or somebody and now, it’s the hottest thing on the radio. You know, old materials being resampled. I’m definitely not the first to invent it, but it is a viable way of working. And I think it actually means a lot because it ends up being sort of a historical palimpsest.

ir: I love hearing about these sonic ruptures happening like in any practice, in any medium. There’s always a reverb or feedback that is influential and how that carries not only through the materials of the quilts but also in other facets of your practice.

SB: Yes! I have another artistic project that’s called Moon Medicine. We’ve been doing musical performances. It’s a 5-piece band. I am the art director and keyboardist, pianist, and one of the songwriters. I have two other songwriters in the group. One is a lead guitarist, Martin Luther from San Francisco, who used to be with Roots and is with the San Francisco Jazz Ensemble right now, and Jah Sundance who is the DJ for Robert Glasper. We started this years ago. In fact, we performed in Kentucky years ago. And we made an album in Kentucky years ago that is finally about to be released on Third Man Records, Jack White’s record label out of Detroit. Kentucky is literally all in the middle of that whole Moon Medicine experience. And one of the songs we wrote while we were there is called “The Great Escapeâ€. There is a video of it in the exhibition. The video was shot by Terence Nance, the director of Random Acts of Flyness on HBO, an incredible young director. It was me and a couple of friends from Morehouse who were basically featured in it. It’s in one of the main galleries, and it provides a sort of toned-down score for the entire show. You sometimes hear it as you’re walking through. This is the best showing of the video because it has a huge wall projection. It was shot on film stock. It was not shot digitally. So you actually really get to experience it. This is the first time that I’ve seen it in its full vibrance. And, featured in the video are a few of the quilts that are actually in the exhibition.

ir: That was my next thought…what story is the video sharing alongside the quilts…

SE: Well, we have our own cinema, our own curator of film. We really want to achieve what artists want to achieve with their time-based medium. We were really pleased to be able to show Moon Rising full screen essentially within the space. That was a priority for us from the beginning. And yeah, I mean, it looks so beautiful in space. And I’m old, so I love things that are shot on film.

SB: There is another video projection in one of the backrooms, and it was actually really good to work with the staff there because we had some sound bleed issues, and this, and that. They were right there on top of it. There was a certain amount of care to make sure that those two rooms, and soundtracks, and everything were balanced the right way. And I think it worked really well. The title of the video in the show is called Moon Rising. The song in Moon Rising is The Great Escape.

ir: What is exciting both of you sonically?

SE: Well, again, because I’m old, I’m just thrilled that Kate Bush is getting a second lease on life these days. And it’s so funny. My daughter is 25. And she, her friends are all so completely immersed in 1980s hip-hop, new wave, little less punk. So we’ve reached that sort of, what, 40-year cycle when everything old becomes new again.

SB: It’s totally true. And it is hilarious to see Kate Bush getting all this attention. I remember listening to Kate Bush when I was a teenager. Punk rock and hip-hop were right next door to each other and then that brought in New Wave and all that. So, yeah, Kate Bush and Laurie Anderson. That stuff was sort of my early entrée into music doing more than just music and this sort of ambient conceptual thing happening behind it. I’ve recently been listening to Paak, and Kendrick’s new album, and a singer named Arooj Aftab. I’ve been listening to her a lot lately. She has a recent album that just came out. And Hiatus Kaiyote out of – wait, they’re out of Australia? Right? Yeah.

ir: I wanted to talk a little about the current state of remixing that craft is undergoing.

SE: One of the areas I’m very interested in along with textiles is ceramics and glass. Crafts in the museum had been a dirty word for a long time. And there are some amazing artists who have always said “I’m a craft artist. Screw you.†I’m seeing more and more younger artists engaging with those different mediums. I find that that’s just so exciting. In terms of textiles, so many artists are turning to it as a narrative medium right now too, which, again, echoes to some extent quilt making, but certainly earlier traditions like tapestries and things like that. I’m so excited, as I say, that the younger generations of artists are really starting to engage with the material and that craft is a good word. I mean, people are taking ownership of it, not trying to sort of run away from it.

SB: Yeah, I’d agree. When I was in grad school – I came out of grad school in 1999 – craft and beauty were both bad words back then. I’ve already mentioned rap, hip-hop, punk rock through this whole conversation. That was another one of my rebellions against the institution at that time, was to start to embrace craft materials because there were so many great artists who were using craft materials and most great artists have high crafts personship. Craft is always part of the conversation. It is good to see people finally embrace it and not feel like they have to whisper it in a dark room because it’s just so potent. There’s so much that can happen with it. I think there’s an accessibility not just for the producer, but for the viewer, to understand some things when craft is at play. That opens up our linguistics and our ability to make nuanced work and have it understood in a way that other materials under mass production can’t necessarily tap into.

SE: I always go back to Joyce Scott who has focused solely for most of her career on “craft media” and through force of will and incredible talent has stuck with it and, you know, creates these works that are glass beaded pieces, but then incorporating larger glass elements that she’s having done by other artisans. The initial approachability of that is the way to draw visitors into the really difficult, upsetting, disturbing subject matter that she deals with in her work. There are others who have stuck with it over time and are now getting their due as well.

SB: I have a question for Scott. What’s coming up on the horizon that you’re interested in?

SE: We have a pretty good-sized Kentucky collection. Largely expressive of white supremacy in the State of Kentucky one way or the other. So we’re entering – probably it will be a couple of years – rethinking those collections and how we contextualize them thematically. Moving away from the more typical lens of art history or even earlier material culture studies. I’m really excited about that. As with everything, it’s long overdue. We have a relatively new director who’s really behind that and excited about it.

SB: That sounds complicated. (laughs)

SE: It is. There are just so many interesting ways to think about it. And a lot of it is tied up in – we’ve talked about Kentucky a lot – Kentucky’s geography, and its historical geography, and its social geography. Is it the South? Is it the Midwest? It depends. You know, it very intentionally has tried to do both. Thinking about the Ohio River as both a perilous portal to freedom before the Civil War, but at the same time also the highway of essentially a second middle passage of the slave trade reaching into the Deep South from Kentucky. This state has a very complicated history, still does today, but thinking about how we can address some of that using objects to do it. And probably working with some contemporary artists too. As a person who collects historical material, I will never collect this institution out of that underrepresentation problem, but I think it’s an opportunity for us to work with commissioned contemporary artists to address different aspects of some of the themes that we’re looking at.

ir: My final question is a silly one. We’ve talked a lot about the lexicon of storytelling. For me storytelling began ancestrally in myth and folklore. But as a child it began with bedtime stories read to me by my mother. I’m always interested in what children books that people identify with the most.

SB: I would say for me it’s probably A Wrinkle in Time, Alice in Wonderland, and The Jabberwocky, and maybe something from Roald Dahl. I like things that have a little bit more sci-fi or darkish tinge to them, but I’m a big fan of fictional narrative because I think humor is a way of dealing with very difficult things. I am also very interested in sort of non-sequitur narratives, narratives that are nonlinear and don’t necessarily conclude. I like to put the onus on the viewer or the reader to make their conclusions. I try to do that in my work as well. I think that influences my selections.

SE: I’m even more embarrassed because my mother was an elementary school librarian. The one book that always sticks out in my mind and it’s not very well-known, it probably was published in the late ’70s, it’s called The House with a Clock in its Walls. It’s sort of this mild horror genre for tweens. It takes place in a Victorian house as all American horror does. That was really one of the first things that middle school got me interested in, architectural history, which is one of my areas of interest too, and particularly the mythology around Victoriana in this country, which is really – speaking of dark – is really dark and very weird.

SB: House with a Clock in its Walls. Okay. Got it.

IIII. EVER EVER AFTER

Sanford Biggers: Codeswitch was on view from March 18 – June 26, 2022, at the Speed Museum. Currently, the museum has the effervescent works of Sam Gilliam (1933-2022) and Sky Hopinka on view. Sanford is working on the project re:mancipation at https://remancipation.org/. And the world goes on…. It’s been close to six months since I sat focused on a screen attentive to the stories of Sanford and Scott – fully immersed in their unfurling of the interplay of utility and function as decorative rupture and the inescapable evolution of quilt making. My thoughts continue to circle the circumference of our talk, and with every pendulum, I am struck ever ever after.

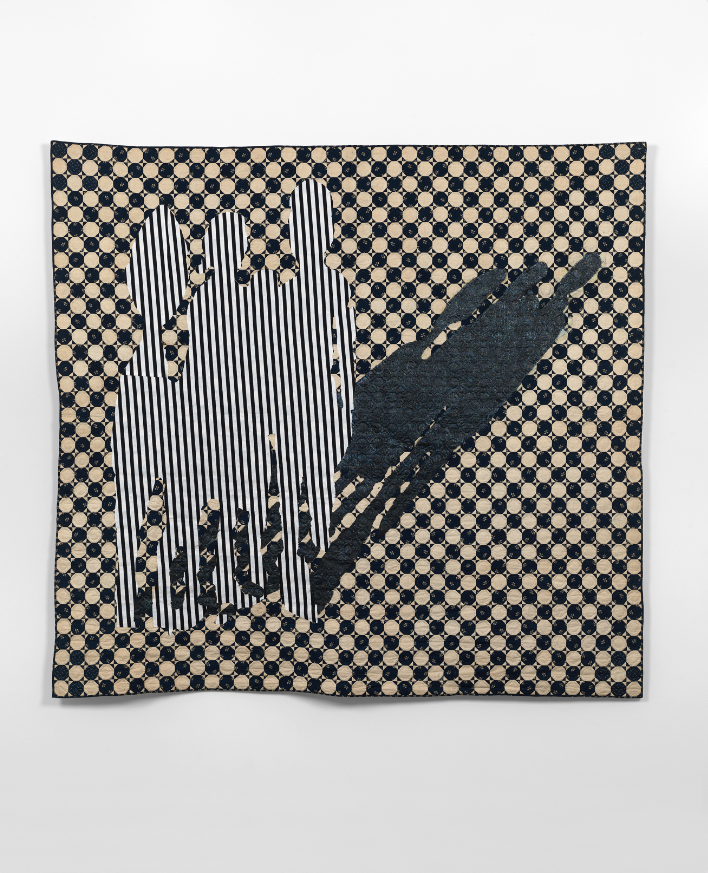

Top image: Sanford Biggers, “Moon Over Ninevah Bay,” 2019. Antique quilt, acrylic, assorted textiles. Cleat/Dibond: 68 x 6 in. Original quilt used: ssbqmat088. © Sanford Biggers and Marianne Boeksy Gallery, photograph by Object Studies.

UnderMain: On the Road sends writers out of Kentucky to explore the visual arts in cities of the Midwest and near South. This program is generously supported by the Great Meadows Foundation.