It is a rare sight to see everyone touching the art, but I knew from past experience what happens when we encounter a work of art by Steve Armstrong. When I turn the crank on Sleeping Gypsy, she plays her guitar and the lion, carved of yellow poplar, wags its tail – both seemingly moved by moonlight and melody.

Like all of us, I can see the theatrics as I rotate the handle; she is a simple machine dependent on my input in order to play her repetitive poetic overture. Up and down her arm moves over five nylon stings plucking out the same tune over and over again. Sleeping Gypsy was created by American artist Steve Armstrong and inspired by the 1897 oil painting of the same name by French Naive artist Henri Rousseau.

Sleeping Gypsy, 2009

Like Rousseau, Armstrong is largely a self-taught artist, but marginalizing terms like naive, outsider and even folk art do little justice when describing these contemporary works of automata; although there are influences of all three in his work. In a Rube Goldberg manner, these kinetic sculptures move beyond simple and ask us to see our individual lives as manipulated theatrics, forever caught in rotary motion until we stop turning the crank. Then, when all is silent, we recognize the transience of our never ending labors in pursuit of the pleasures of this life.

Since his first one-man show at the Heike Pickett Gallery in Lexington, Kentucky in 1983, Armstrong has made over 400 automata. They are not all complicated works of craft, but they are all authentic works of art – some full of a grinding candor that exposes Armstrong’s deep meditations on life and art.

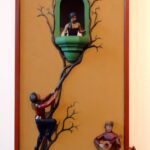

Ozymandias

Consider for instance Ozymandias, based on the poem published in 1818 by English romantic poet Percy Shelley. Armstrong made this work of art in recollection of this sonnet, which he had to memorize in high school. Specifically he recalls, via a Facebook chat, the last lines and repeats them as, ‘look on my works, ye mighty, and despair…now all that remains is a shattered visage.’

I met a traveller from an antique land Who said:

Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert. Near them, on the sand,

Half sunk, a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them and the heart that fed:

And on the pedestal these words appear:

“My name is Ozymandias, king of kings:

Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!”

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.

– Percy Bysshe Shelley

Shelley’s words render power ephemeral, declaring art and emotional truth as the only things that are permanent in the end. Armstrong’s work evokes this reality with such confidence that seems likely that they are from the hands of someone who understood such universal concepts at an early age.

From a number of YouTube videos, we know that Armstrong grew up frequenting antique shops and auction houses around the world to develop a life long love of whirley gigs. When Minimalism unraveled and Pop Art and Conceptualism emerged, Armstrong was dismantling antique toys and carving pieces and parts for his theatrical stage. His fascination with invention and craft held his attention even as new media gained ground and animation could have been realized at a far more sophisticated level. His works are postmodern in that they are a montage of iconography from many cultures. Whether modeling Egyptian kings, Italian lovers, Buddha or the nostalgic props of Americana, Armstrong discovers the same moral themes; each interlude prompting us to accept a more meaningful life as opposed to that guided by earthly temptations.

Dogs of War

Dogs of War, detail.

His inventions are laboriously contrived to perform the simplest of tasks: Dogs of War is a Rube Goldberg in both a mechanical and metaphorical sense. With the turn of a crank, dogs race around, gears clink and clatter compelling the male figure to move his mouth. Is this cold, blind head a warmonger encouraging his people or a nation to go to war? If so, Armstrong deliberately makes this reference ambiguous as many of the features in this head – heavily delineated eyebrows and mouth – recall images of Buddha.

Heartland

Heartland, 39 x 37 x 24, 2010

Heartland is a disturbing contraption filled with busy figures serving what must be the corporate machine – portrayed by the larger gold-spattered figure at the top of the factory buildings. It is old, a thing of the past. Dripping with enormous futility and the sorrows of jobs lost, we witness nothing being accomplished by the hard work of these particular laborers. Their size in relation to the set in which they toil signifies what we already know – that their efforts are in vain. It is this dark sort of danse macabre that pervades much of Armstrong’s work.

Blue Garden, 2013

In the underwater scene of Blue Garden, emerald sirens disguised as mermaids summon us to see what is inside the oyster shell at the bottom of the composition. This shell is closed on first approach. Four or five determined cranks of the handle opens the shell to reveal a human skull inside, not a pearl. The contrasting nature of the morbid and the beautiful recalls the Vanitas of Dutch artists working in the 16th and 17th centuries. Then and now, such imagery reminds us of the meaninglessness of earthly pleasures and the certainty of death.

Hand-carved performers with their various props act out the improvisations of a true artisan. It is a Commedia dell’arte and we are not only spectators, but participants, Pierrot characters in a theater of extreme tenderness where too many subliminal warnings foreshadow something unknown. Spring, a figure whose pose is that of a traditional Indian dancer summoning the blooms of her branches, beckons and warns as her head jerks forward and back again and again in an effort to play her pan flute. We hear only the odd harmonics of the wooden gearing.

Monolith

One of Armstrong’s largest works titled Monolith is a collaboration with the his son Patrick. It is a wooden box into which the artist invites us to join the troupe. On stepping in, I saw that Armstrong’s figure was dancing. I knew she was another simple machine like the Sleeping Gypsy, but this time I was not assisting. She was dancing in the small space beside me; her many carved positions rolling over and over with a magic that only a zoetrope could deliver. She was dancing a happy dance. I was not. Did Armstrong put me on the merry-go-round or did he make me realize I was already there?

The poetic and evocative themes of this work acknowledge humanity as the beating heart of the world and this is Armstrong’s contribution to contemporary art. He invites us to consider our moving parts, to disassemble and burnish off the high gloss of individual power, self and wealth and worldly possessions; to examine ankles, wrists, elbows and knuckles together like the not-yet-assembled carvings that make up these kinetic sculptures. And, then reassemble them into something we might be forgetting – our collective humanity reawakened to the things that really matter. Who knows, our final contraption just might move without turning the crank.

First published by AEQAI.

Enjoying the UnderMain experience?

Help us sustain our coverage of cultural affairs in Lexington, Kentucky.

Every penny goes to content and production. Thank you!

Click here to help under-write UnderMain