“Afloat: An Ohio River Way of Life†had its origins in the spring of 2018 with an email from Bill and Flo Caddell, guardians of the reputation and ideals of Harlan Hubbard (1900-1988), artist, writer and environmentalist. Inspired by Henry David Thoreau, Hubbard attempted to live a life as close to nature as possible, and he and his wife Anna subsisted mostly on what they were able to raise, catch or barter. They lived at Payne Hollow, on the banks of the Ohio River, a mile away from the nearest road, in a home without electricity or other modern conveniences.

Hubbard left his artistic legacy to the Caddells, who possess the largest collection of Hubbard’s oils, watercolors and woodblock prints. They asked if I would like to write a foreword to a book on Hubbard watercolors, scheduled for publication in 2020 by the University Press of Kentucky. The Caddells, with Hubbard scholar Jessica Whitehead, were to be the principal authors.

They had originally asked Charles Venable, director of the Indianapolis Museum of Art, to write the foreword; he declined but suggested me as a substitute. I told the Caddells that I would like to visit, and asked permission to bring John Begley with me. John had been director of Louisville Visual Art (LVA) and I had been director of the Speed Art Museum; after leaving our executive positions, we both taught in the Critical & Curatorial Master of Arts Degree program at the University of Louisville, often as a two-person team.

John thought he was simply going along to look at some pictures, and I went to make up my mind as to whether I liked the work well enough to want to write about it. We were both strongly smitten with Hubbard’s fresh, improvisatory and spontaneous watercolors, the visual equivalents of the lively, brief descriptions of the natural world in his journals.

Fortuitously, while doing research at the Filson Historical Society, I had overheard that it was planning a show based on Mark Wetherington’s studies of the shantyboat community that had thrived at “The Point†on the banks of the Ohio in Louisville in the 19th and 20th centuries, until mostly wiped out in the 1937 flood. Hubbard is best known for his book Shantyboat: A River Way of Life (1954) chronicling his trip down the Ohio and Mississippi with his wife Anna, so the Filson show would be relevant to Hubbard manifestations elsewhere.

I then went to the Department of Archives and Special Collections at the University of Louisville, which has the largest holding of Hubbard’s manuscripts. Would they consider doing a Hubbard show simultaneously with the Filson’s? The librarians agreed.

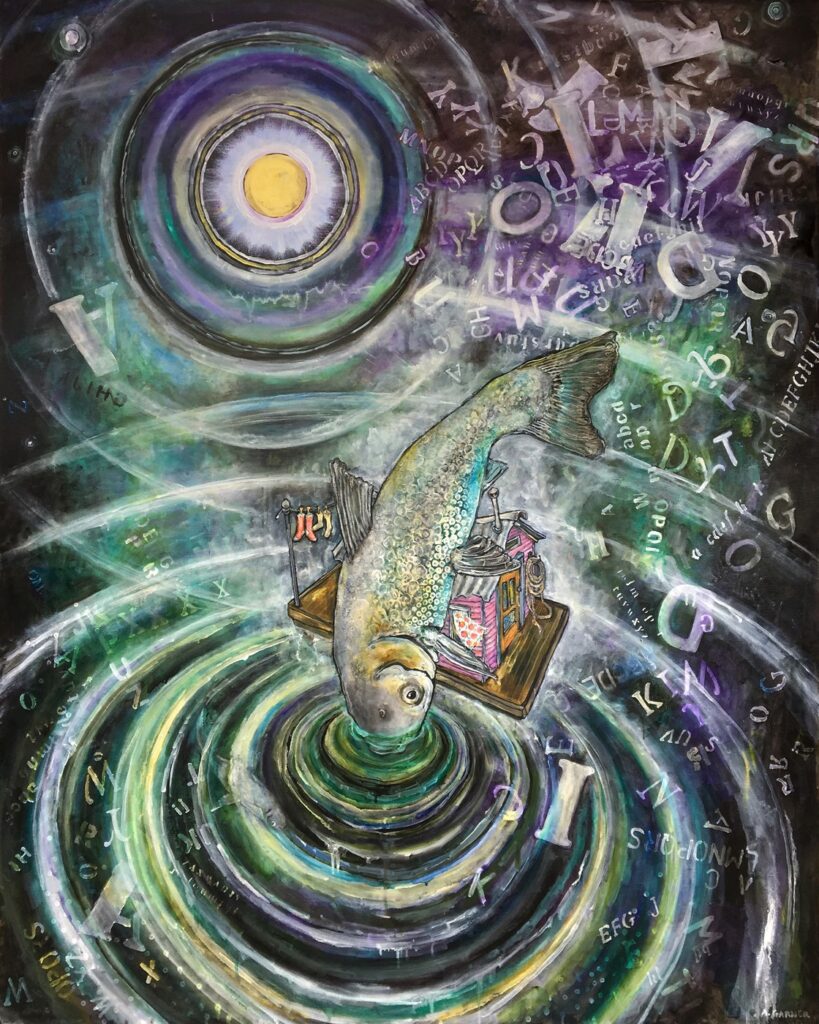

Shortly thereafter I saw a painting by Angie Reed Garner depicting a shantyboat. She had developed an iconography of shantyboats, Asian carp, mules and other imagery inspired by Hubbard to call attention to recent efforts to destroy the camps of homeless people living outside of the flood wall in the Butchertown neighborhood, close to where shantyboaters had lived a marginal existence in their homemade houseboats at The Point.

With three committed Ohio River/Hubbard-centric collaborators, we held an initial meeting on board the Belle of Louisville in August, 2018, drawing an enthusiastic group of staff from a variety of museums, volunteers, enviromentalists, gallerists and others. From there, the project mushroomed: the Caddells graciously agreed to lend their watercolors to the Frazier for a show that John Begley and I would co-curate.

The Swanson Contemporary Art Gallery agreed to mount “Currents: Contemporary Art on the Banks of the Ohioâ€, a brilliant show of 14 artists contending with the river, or with the Hubbards as muses. The Commonwealth Center for the Humanities and Society signed on to provide professors to lecture about Ohio River history and culture. We were under way!

We now have nearly 20 academic organizations, galleries, history museums, art museums, outdoors and environmental groups united in focusing on the Ohio River in 2019 and we will continue to add partners throughout the year. We refer to ourselves as a consortium, or a collaboration, but have studiously avoided creating a 501(c3) or having a board. Donations are processed through the Community Foundation of Louisville to ensure deductibility. Our model is deliberately open-ended and fluid.

Over time, a larger purpose emerged:Â to call attention, as our elevator speech puts it, to the Ohio River, its beauty, its needs, and its unmet potential. Â This new consortium has the ambition of providing a platform for environmental groups in renewing and recasting attention to the Ohio River, and creating dialogue among sectors that do not often come together.

– The Ohio River’s beauty: Hubbard wrote frequently of his prolonged contemplation of the river, and decried those who would ignore the beauty of the everyday.

– Its needs: there are 25 active coal-fired power plants on the Ohio, a source of toxic mercury, and new revelations suggest the precipitous danger of coal ash impoundments and landfills.

– Its unmet potential:  the closure of the Jeffboat shipyard on the banks of the Ohio in Jeffersonville, Indiana, will open a mile of shoreline for development or, ideally, park lands. The Ohio River Recreational Trail proposes a Blue Trailfrom Portsmouth, Ohio to Louisville. The trail would be a means of promoting ecotourism and increasing opportunities for fishing, boating, paddling and cycling, as well as retail, lodging and food sales.

What are possible impacts? First, Kentucky is second only to Alaska in the number of miles of navigable waterways. Our consortium could be replicated elsewhere in the Commonwealth or “Afloat†could extend its reach.

The second issue has to do with artistic practice. Subjects in art have been viewed with suspicion for at least 75 years. I grew up in an age in which the best works of art were often titled, “Untitled†or simply numbered, in an attempt to let the work speak directly to the viewer and permit a universality of expression and meaning, leaving the art unbesmirched with words. Implicit in this attitude is ‘art for art’s sakeâ€, a 19th Century notion rejecting art’s utility. In their provocative book, Art as Therapy (2013) Alain de Botton and John Armstrong argue:

The saying ‘art for art’s sake’ specifically rejects the idea that art might be for the sake of anything in particular, and therefore leaves the high status of art mysterious – and vulnerable. Despite the esteem art enjoys, its importance is too often assumed rather than explained. Its value is a matter of common sense. This is highly regrettable, as much for the viewers of art as for its guardians. What if art had a purpose that can be defined and discussed in plain terms? Art can be a tool, and we need to focus more on what kind of tool it is  – and what good it can do for us.

Our multiple exhibitions, events and lectures are not going to soon lead to steps that will increase oxygen levels in the Ohio. But it may test whether cultural manifestations can influence the collective narrative and spur thought leaders to confront the fraught issue of the water those of us living on the banks of the river drink. Rallying around a single subject does not have to be about a specific meaning in order to be meaningful. Meaning is provided by the context of all of the manifestations of attention to the Ohio River in the “Afloat: An Ohio River Way of Life†consortium.  In  the interim, openings and lectures in the early months of this year have been met with record audiences.

Harlan Hubbard believed in the eventual impact of his fierce determination to live in harmony with nature and in opposition to commercial and industrial forces. In 1942 he wrote:

Against what I thought wrong and false, I have long been conducting a one-man revolution, faint and under cover but growing stronger, and sooner or later it will be revealed. It may as well be now. My case should be presented and stood for, even if by such a small minority. It is a strain of Americanism almost lost. It is the hope of the future.

[aesop_video width=”09″ align=”center” src=”youtube” id=”vbu9poGWOn4″ disable_for_mobile=”on” loop=”on” autoplay=”on” controls=”on” viewstart=”on” viewend=”on” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

For more about “Afloat: An Ohio River Way of Life†visit https://afloatontheohio.com/.

TOPMOST IMAGE: Ray Kleinhelter, “Above Grassy Flats”, Oil on Linen, 2019, 40×30″