Cara Blake Coppola’s contribution to our essay challenge is about a life-altering turning point of great significance. Her essay is excerpted from her blog whitewillowsite@wordpress.com. She recalls the day when she learned that her daughter had special needs. The story unfolds in Lexington.

There is a poem/story that I have become familiar with since meeting Willow Eve. It is called “Holland†or something like that, and it compares the reality of raising a child with special needs to a misguided vacation that, though promising Venice or some such exotic locale, instead delivered the vacationers to Holland.  “Oops,” the story goes.  “Instead of gondolas and wine and pasta, you get windmills, and tulips. Maybe some wooden shoes as souvenirs.”  Not quite the relaxing, stimulating vacation you thought you were going to get, but hey, you’re still on vacation, right?

I’m certain that when I first read that story, probably in those fog-filled days of Early Intervention and sleep-deprived delirium, it brought me comfort, and more than a few tears. After fifteen years, however, I find the metaphor lacking.  Because, really, who goes on vacation for fifteen years? And does that mean I’m supposed to assume that I was on vacation in Venice for three and a half years before I had Willow, when Sierra was the only human being I was responsible for? If so, I think I need a refund, because I don’t remember gondolas, or wine, or any kind of vacating in any way. I remember being tired, and laughing hysterically, and lots of pee, poop, and vomit. Somehow I think the Venetian Tourist board would be amiss at this comparison, though I’m sure some college students have had Venetian vacation stories such as this.

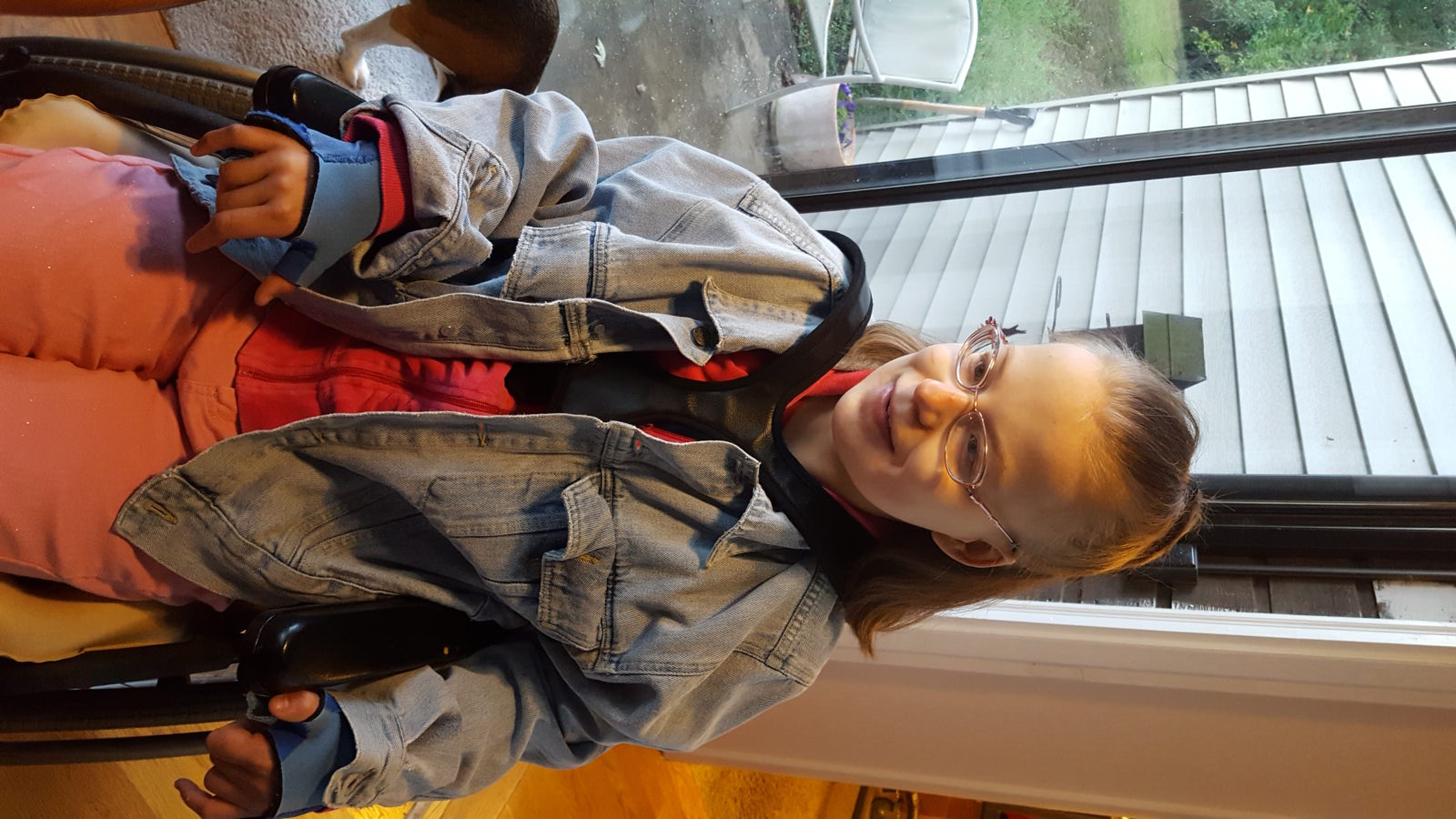

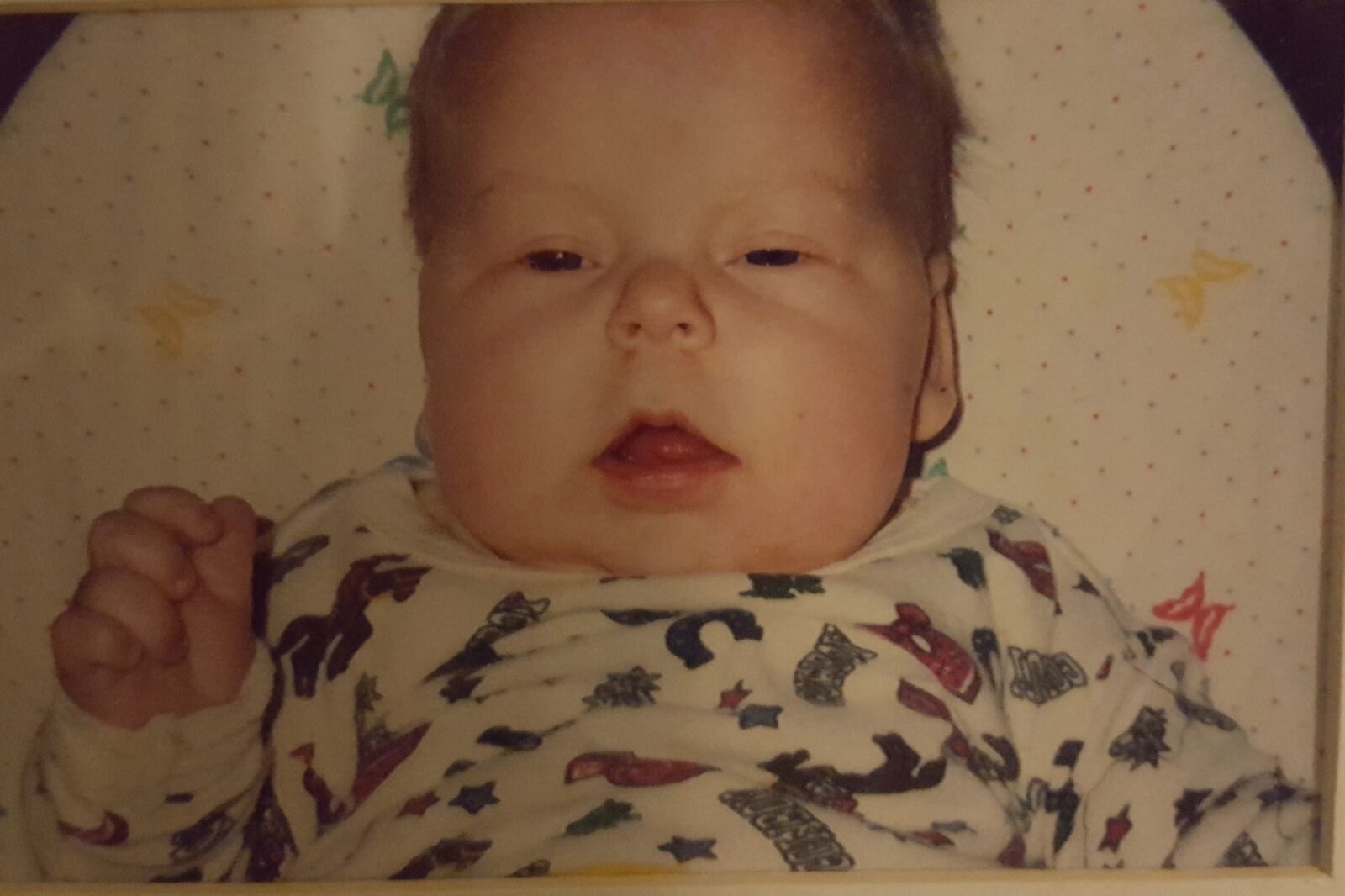

Willow was a sweet, tiny little baby girl, so loved by her big sister and the dog Maggie, who licked her cheek and wagged her tail in delighted greeting when Willow was brought home from the hospital. We adjusted accordingly, and got back to living our simple life.Â

By the time spring burst into the Kentucky countryside, our small bohemian apartment was bursting with color and toys, and spoke of a happy family. That, however, was the calm before what would become our personal storm, the blissful ignorance we allowed to envelope us before the evidence started piling up.Â

Soon, too soon, we would be forced to accept the reality that Willow was not developing as she should, that her frequent crying was indicating more than just colic. Taking place over a few weeks, totaling one very long month during her fifth month of life, we would return from the hospital once again with Willow, though this time it was very, very different.

There was a day, in Willow’s fifth month, when everything started coming together, like sand shifting its way down a funnel, and that is where our story really begins…

“Now boarding for Holland, please buckle up. It’s gonna be a damn bumpy ride.†Taking off…

It will be a challenge to me to keep this narrative at a decent length, but this particular day was the exact day it all began. There were hints, or foreshadowing if you will, yet our immersion into the special needs world was primarily condensed into one day on the monthly calendar. Intense does not begin to describe it. The difference between Venice and Holland is not sufficient; maybe the difference between living on Frontier America and suddenly being transported to the bar where Han Solo shoots first is a closer comparison.Â

It got to the point where, by the end of our weeks’ vacation at the beach that fifth month of her life, Willow would only nurse at night, when she was too exhausted to fight anymore. But then she would nurse and fill up and sleep well, and she wasn’t losing weight, so we just kept trying to eliminate the variables.Â

Driving home was a headache and ibuprofen rich endeavor, and we returned home to our little apartment exhausted and tanned, but not really feeling relaxed from our “vacationâ€.Â

Upon our return, time seemed to speed up and get really scary. I went to visit a good friend, my midwife and doula who had been there when Willow was born. She took the baby and immediately lifted her up and down, as if weighing her. “Is she losing weight?†she asked suggestively, waking a growling dragon of stress and anxiety in the pit of my soul. “Is she?†I asked, tears immediately coming to my eyes.Â

Soon after, I couldn’t get Willow to nurse at all, so we got some soy formula. At that point, it was an early spring morning in Kentucky, characteristically cold and dreary. I tried and tried to give Willow the bottle that I hoped would fix everything, but she refused to take it. She just screamed weakly, and I cried.Â

Quickly, we headed downstairs to visit our neighbor, another midwife who owned a glucometer. She tested Willow’s blood sugar. I will never forget the look on her face as she read the screen. “Cara, her blood sugar won’t even register, I think you need to take her to the ER.â€

What followed was a day that was so surreal and frightening, I seem to remember it in foggy patches, like a dream that you can’t shake for hours after you wake up.

We went to our local hospital where Willow had been born. They asked many questions and made many, many false assumptions. It is a cruel trick of the human mind that we can see things in hindsight so much more clearly than we do at the present. At that point in her exhaustion and hunger, Willow’s eyes were shifting erratically back and forth. “Does she always do this?†one doctor asked, pointing to her shifting eyes. “Um, I don’t know. She’s really tired I think. She won’t eat…†I kept saying. They asked me if she was blind. Blind?? No, I was sure that she had focused on my eyes while nursing, that she had paid attention to the rainbow paper chains that decorated our living room. In hindsight, however, that damned gift that comes too little, too late, I realized that she never did stop shifting her eyes. That goofy, googly eyed-ness that Sierra had had when she was born (when I got scared and made Dad rush her to the nurse, because clearly she was broken) was a phase that Sierra had quickly outgrown. There was one cute cross-eyed picture of her at Mother’s Day, and that was the last of it. She was only a month old then. How could I have forgotten that? How did I not know Willow’s eyes weren’t behaving normally?

The next assumption was seizures. Perhaps her shifting eyes indicated seizures? They asked me. All I knew of seizures at the time was an image of someone shaking violently, drooling and passing out. No, Willow had definitely never done any of those things. She just wasn’t thriving anymore, she wasn’t growing anymore, and she cried…all the time.Â

Brain damage, they reported before Willow was even out of the CAT-scan. Retardation. Epilepsy. Possible blindness. The only conclusion of which they were certain, though it didn’t stop them from making guesses that shook me to my core, was that Willow’s case was out of their expertise. It was time to take a ride up to the big city and see what those doctors might know.

I knew the situation was worse than I might have imagined when they led us to an ambulance, shut the door behind Willow and I, and turned the sirens on full blast. Dear God, I remember thinking. Never in my life had I been in an ambulance with the sirens on. Not with my father’s almost heart attack, not with my mother’s anxiety attack she thought was a stroke. But here, my tiny, frail baby was strapped to an adult sized gurney, wrapping her weak little hand around my finger, as the sirens bellowed our entire journey towards Lexington.

It was in that ambulance that I met my first angel. I’m a Catholic by upbringing, Christian by nature, but claim no denomination. I’m not a terribly religious person; to me it is more of a culture than a spirituality, like my Italian grandmother’s routines of putting rosaries on the bushes outside to ask God for good weather, or putting some of the Christmas hay from the Church’s manger in your wallet for prosperity, and the ornate saint doll that sat on every matriarch’s mantle, robed in velvet and silk and lace. But I do remember many myths of God or Angel’s posing as some wayward person, a humble beggar or blind man. These archetypes sometimes pass knowledge, and sometimes propose a challenge for generosity. Those who pass the challenge are enlightened and praised; those who fail are doomed to suffer their ill choices.

The angel I met that day was one who passed knowledge, and I wish to this day that I remembered his name. He was one of the EMT’s that travelled in the ambulance with us that day. He sat in the back with Willow and I as his partner drove, and quickly noting the look of absolute desperation and fear that I’m certain I had plastered all over my face, talked with me calmly the entire grueling ride. Unlike everyone else we had met at the hospital, who seemed to feel free to hypothesize away about any myriad of ailments that might be afflicting our daughter, this man kept his opinions to himself. What he did, though, is tell me his story. He was a father. His wife had birthed triplets two years ago, and their premature children had met with many struggles along the way. Maybe it was twins. I honestly don’t remember, except that it was a multiple birth. He didn’t tell me what all the challenges were that they were meeting. He didn’t mention a single medical ailment, or any tests or needles or tubes that may have been involved in their challenges. What I do remember him talking about was strength; the strength of his wife, who he clearly adored, for carrying those children as long as she could to keep them strong, and the strength of his children, for overcoming any limitations life, or anyone else, may have imposed on them.Â

I don’t know, maybe he had been there the whole time in the ER and heard all these diagnoses and terms flying around and saw my instinctual urge surface, the one that tells you to run and hide somewhere dark and close; anywhere far, far away from there. Maybe he went through the same experiences with his babies. But he told me exactly what I needed to hear right then, and for that I am so, so very grateful. To this day, after meeting several more angels along the way, and even more thoughtless, over-diagnosing individuals, I remember him. Not his name, dammit, but I do remember him. I still hope someday he will remember me and reintroduce himself, but he was a very cool guy who gave me a bit of comfort on what, at that point, was the worst day of my life.

Willow and I were led from the Ambulance to the ER swiftly and put into a curtained enclosure. Quickly feeling like an exhibit in a circus, people started coming by. They would stand, and stare. Doctor after doctor would look at Willow, touch her without asking permission. They drilled me with questions, often not waiting for me to finish talking before they began the next question. This is a phenomenon that I have come to deal with in the medical and special needs world, where experts talk as fast as they think, and social norms of not interrupting are thrown out the window; at the time, however, I was completely floored. Sierra had been so healthy, not one round of antibiotics her entire three years, and I had no experience with such highly educated specialists. Their brains are machines of information, something I have come to deeply admire over the years, but the awkwardness of enduring many “conversations†like this soon sapped all my energy.

They asked questions about everything: the pregnancy, my diet, my habits, the birth, nursing, hell, they practically examined me as well. They touched and prodded Willow all over, turning her head back and forth, shining bright lights in her eyes, tickling her feet. Willow fussed and cried through the entire procedure, her eyes shifting all over without recognition.Â

I don’t know how much time passed that way, I truly remember very little about the UK ER that day. It was clear that we had to be admitted, that any number of tests had to be run, and we were soon wheeled down many shifting hallways until we emerged into the University of Kentucky Children’s Hospital.

The old Children’s Hospital at UK is a bright and imaginative place, and I immediately enjoyed being in that building. They have since opened an entirely new Children’s Hospital.  In the old hospital, which we were visiting for the first time that day, the elevator opened to a lobby where an artist had installed a truly remarkable perpetual motion machine. It was mesmerizing; a continuation of belts, gears, levers, and engines that moved a dozen or so balls around and about a labyrinth of activities. The balls went upstairs and down wooden blocks painted like fish, where each block made a different note as the balls cascaded downward. At one point a ball was dropped and bounced off a platform, only to land perfectly into a basket several feet up, where it continued on its course around the machine. What an amazing thing to create in a place where magic and whimsy were unlikely to be found.

As we proceeded into the hospital, following the nurses who spoke kindly to us both, we rolled past the corners where sculpted trees rose up to a ceiling enchanted with twinkling lights that at night were turned on to make a starry sky. Rooms in each hallway were filled with books, toys and wagons for play, and a toy cart was wheeled by volunteers from room to room, handing out free toys that had been donated by thoughtful people. As far as hospitals go, this place was almost as fun as a Children’s Museum.

At some point after we were installed into our own private room, Dad showed up loaded down with clothes, sleeping bags and food. Willow was put into a medical crib and hooked up to an IV for fluids. The nurses soon delivered a bottle with soy formula, and I gratefully began to feed Willow her first real bottle. This was a bittersweet moment for me. My main thought was to be thrilled as she hungrily swallowed three small bottles in a row and burped happily to be full.Â

But in honesty, I felt like a complete failure. I was a proud breastfeeding mother. Sierra had thrived beyond measure on the milk I produced for her, and never needed any kind of supplement. Willow had reacted so strongly against my milk, in hindsight since the beginning of her life, and I felt like I had bombed the most basic of maternal requirements, but Willow had made up her mind. Bottles were easier and the formula within contained no threat of allergies. She had made peace with her decision, but it would be years before I finished grieving for our aborted nursing relationship.

As soon as we were officially admitted to the hospital, the doctor visits began. We were swiftly introduced to a continuously shifting parade of people in white coats, scrubs and dress clothes. One person would breeze in with a plastic tote filled with vials to draw so much of Willow’s precious blood into the plastic tubes with different colored stoppers. An IV was hooked up to her tiny little arm, and her elbow had to be splinted so she didn’t pull it out. Soon her clothes were changed into the yellow and blue ones with koalas that the hospital provided. She wouldn’t wear her own clothes again for a week. Her small feet were poked repeatedly for blood samples. We rolled blankets and put them around the edges of the cold, metal bars of the hospital crib, and soon a kind face wheeled by with toys and books to help break up the monotony of white on white. On that day, Willow was given a fuzzy, soft flower that tied to the edge of the crib. A bee hung down; when pulled, the bee slowly made its’ way back to the flower, playing a sweet little tune in its journey. Willow still has this flower.

This was the very first day of our journey together into the world of being Medically Fragile and having Special Needs. A long tale, that day continues in my memory to be stretched in length way beyond twenty-four hours. It is the first chapter in a story that is almost sixteen years long, and filled with many more hospital visits, doctor visits, therapy, Special Education meetings, Shriner’s, wheelchairs and more.Â

We rolled through that door and into that world on this very first day.