Everyone seems to have explanations of the homeless.

“They are just lazy bums who don’t want to work.”

“I heard that some of them make like $60,000 a year begging.”

These theories help us justify our rationales for declining to help people we see on the streets by dismissing their struggles as self-inflicted or too complex for our intervention.

But how many of us have actually sat down for a heart-to-heart conversation with someone who is homeless? A genuine conversation free of judgment, preconceived notions, and self-righteousness, entered into with only a genuine compassionate curiosity and desire to understand?

Casey Yohe and I wanted to do this and take it a step further. We wanted to see how these individuals who have been cast out of regular society survive and what do they do, day-to-day. So we immersed ourselves into their reality and raised some money for a homeless shelter along the way.

Casey Yohe and I wanted to do this and take it a step further. We wanted to see how these individuals who have been cast out of regular society survive and what do they do, day-to-day. So we immersed ourselves into their reality and raised some money for a homeless shelter along the way.

To accomplish this we launched #BringUsHome. The goal of this social media-based initiative was to remain homeless until our friends and family “brought us home” with donations towards our goal of $3,000 which we would then donate to The Catholic Action Center, a local resource and shelter for the homeless.

To ensure our efforts were sensitive and respectful, we got the approval not only of service providers, but individuals who are actually homeless.

And then we laid out some ground rules;

We would bring with us no belongings except a backpack, a phone, and a phone charger.

No money.

No begging for money on the street.

No returning home until we reached $3,000 on our online fundraising page.

Our guides

Ginny Ramsey, the director of the Catholic Action Center found a mother and daughter who were both homeless who wanted to serve as our guides throughout the experience, allowing us to shadow them for the duration of the project. While many of us would be uncomfortable with this level of intrusion, Pam and Sonya said they were really excited about it because they truly wanted to show the public what it is actually like to be homeless.

When do we get to be lazy?

No money in our pockets meant we walked. A lot. Everywhere. It felt like we were constantly marching along this invisible trail of misery from shelters to churches to parks to libraries to anywhere that provided some brief reprieve from the impenitent sun. Keep in mind, this was a pleasant, dry weekend in late May. How did anyone do this in February when Lexington was rocked with blizzards and subzero temperatures? Or in March when we got pounded with more snow on a Wednesday and Thursday than any two-day snowfall in Lexington’s history?

“It got pretty bad. You find out what you are really made of,” remarked Pam, not breaking stride out of fear we’d miss out on the lunch being handed out in a parking lot.

[aesop_quote type=”block” background=”#282828″ text=”#ffffff” align=”center” size=”3″ quote=”“It got pretty bad. You find out what you are really made of,” remarked Pam, not breaking stride out of fear we’d miss out on the lunch being handed out in a parking lot.” parallax=”off” direction=”left”]

“When do we get to be lazy?” I replied, a half-joking, half-serious inquiry as to when we get to rest.

A terrible irony of homelessness is that you have all the time in the world, yet none of it is yours. You eat dinner when the church serves dinner. You get transportation when the bus comes. You enter the shelter when they say you can and you leave when they say you must. Privacy is nonexistent and you relieve yourself in the public library’s bathroom when it opens. You have no control over your personal world because it is entirely in the hands of others.

Flying a sign

The endlessly debated moral conundrum: What do you do if you see someone holding a sign begging for money?

“Oh yeah, flyin’ a sign,” said Pam. “I can tell you right now I have never done such a thing in my life.”

I was surprised to learn that the folks we see on the corner asking for donations represent only a tiny portion of the homeless population – most people on the streets have never “flown a sign.”

“It’s upsetting because they make us all look bad,” said a frustrated Sonya.

[aesop_quote type=”pull” background=”#282828″ text=”#ffffff” align=”center” size=”3″ quote=”“It’s upsetting because they make us all look bad,” said a frustrated Sonya.

” parallax=”off” direction=”left”]

This strong, palpable resentment among the homeless towards people who fly signs was consistent throughout most of our conversations; most proudly proclaimed they have never done it. In fact, most of the individuals Casey and I encountered were doing everything in their power to get back on their feet. Jessica, for example: one of the most determined individuals I have ever met, taking classes, working three jobs, and saving up money for her own place.

The shelter

To avoid taking a bed from someone who needed it, we were going to stay on the streets until Ginny insisted that we stay at The Community Inn, because there would be extra beds due to the nicer weather, but also so we could get the entire experience of sleeping in the same place as others who are homeless.

It isn’t until you stay in a shelter that you are confronted with the engulfing brokenness that many people are struggling to overcome. It’s the underside of society that you avoid thinking about. While the rest Lexington sleeps soundly in safe homes, over 1,000 individuals each night either stay on the streets in Lexington or seek refuge in a shelter.

You quickly realize that the reasons people are homeless are often complex and intertwined. Untangling them is a challenge.

The untreated mental illness combined with an absent familial support system.

The overwhelming grip of addiction combined with one mistake in the past that makes you unemployable.

The years of violent, sexual abuse combined with a dearth of self-esteem, self-worth, and confidence.

Compassion

Within the homeless population, I witnessed more compassion, respect, and manners than exhibited by the very society that has written them off. As Casey and I became more immersed in their reality, I saw example after example of this selfless love for one another: looking out for each other; sharing food, cell phones, clothes, and other necessities.

At one point, as I was staring aimlessly in a sleep-deprived trance, my gaze was interrupted by the shine of a cold pop can that had been placed in front of me. I looked up and Pam said to me “Looked like you could use it,” with a warm smile. The beauty of that moment is nearly ineffable; a woman, beat up and beat down from years on the streets with nothing to her name but a backpack and a resilient smile still chose to spend her last quarter on a stranger.

Drugs

If you’ve never been homeless, you may have wondered why anyone would spend their last dollar on drugs and alcohol. At the peak of the misery of my experience while homeless I wondered no more: If that was my existence every day, with no sign of it ending and no idea how I would solve the suffocating problems that plagued me, I would need something to escape the unavoidable pain. I would need something to alter my reality by any means necessary to find some distorted sense of solace, no matter how detrimental it may end up being.

“Y’all gotta git”

The worst experience of my sojourn in the reality of homelessness was our visit to a local McDonald’s.

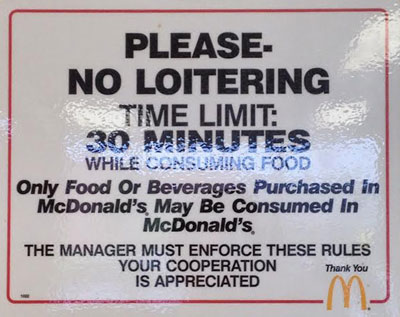

After comparing sleepless experiences and the lowlights of our sweaty nights, my homeless family and I began our nomadic march to the nearby McDonald’s to begin the morning. Somnolent and disheveled we arrived at the golden arches and were coldly greeted by this sign:

After comparing sleepless experiences and the lowlights of our sweaty nights, my homeless family and I began our nomadic march to the nearby McDonald’s to begin the morning. Somnolent and disheveled we arrived at the golden arches and were coldly greeted by this sign:

I thought it was odd but forgot about it as we sat down with our purchases, united in pleasant conversation and fellowship sponsored by caffeine and camaraderie. Despite the inevitable reality of homelessness that waited outside the door, this joyful respite provided fleeting refuge from the misery as we joked, told stories from our childhood, and nestled in the solace of our newly formed friendships.

Then, abruptly, devoid of hospitable pleasantries or even scripted perfunctory dialogue, an employee announced that if you have been there for 30 minutes or more it was now time for you to leave.

Before I could question or object, the McDonald’s employee began snatching receipts out of the hands of the paying customers I was with, scrutinizing the time-of-order details on their slips, and responding dismissively with “You’ve been here for longer than 30 minutes, y’all gotta git.”

And just like that, the restaurant chain that once touted in a merry jingle that they were “your place to be,” brusquely made it clear that that meant everyone except us. We embarrassingly and submissively made our way to the exit, gathered our backpacks in the doorway then walked outside, reconvening near the door. Before our homeless friends could finish telling us how less-than-human it makes them feel, a different employee came outside and barked “C’mon, y’all gotta go. Y’all can’t just stand here by the door,” and we were shooed away like pesky gnats at a picnic.

And to think, some local businesses in Lexington will even allow dogs in their establishments.

The most marginalized of marginalized

It was from experiences like this abysmal treatment by McDonald’s that I realized the homeless population is truly the most marginalized of the marginalized. Imagine if a restaurant employee had ejected a customer based on their skin color? Or applied this “policy” to someone because of their sexual orientation?

During my brief time being homeless I realized that marginalized might not even be the best way to describe people who are homeless as that suggests they are still active peripheral participants of society. When you are homeless, you aren’t even on the edge of society—you are left out of the picture altogether. You’re an afterthought. People avoid talking to you or making eye contact. When you are thought of, it is more along the lines of in preparation for a storm or plague, like “How will our event be affected when the homeless come?”

We’re all the same

When you refer to someone as “that homeless man,” it immediately conjures up an image and a stereotype that suggests the chasm between your existence and his is so wide that he might as well be from another planet. Yet as I sat at Phoenix Park on our donated blankets among several folks who were homeless, I realized that despite many of the ostensible differences between people who have homes and people who don’t, we’re all the same.

They wanted the same things that we all want, regardless of our living situations. They wanted friendships. They wanted respect. They wanted to overcome the barriers keeping them in the streets. They relied on their own community and strived to fit in amongst people. They laughed with each other, they heckled their friends, they gave in to the occasional donut, they reminisced about the old days with a hopeful vision for the future. They prayed, they thanked, they sang goofy songs. They had bad days and sometimes the bad days would win.

For some reason, this detail about their life—that they do not have a permanent home—instantly becomes the characteristic by which we define their entire existence. Yet each time I met an individual who is homeless and heard their story, I realized we are all only one or two steps away from being homeless. It could happen to any of us.

We’re all broken in some way. Some of us with homes are merely able to hide it better. When you are homeless, you often wear your mistakes on your sleeve through your appearance or mere existence. Your lack of privacy extends to the inability to conceal the errors you have made in your past and forces you to live in a transparent manner, more transparent than most of us could ever dream of being.

[aesop_quote type=”pull” background=”#282828″ text=”#ffffff” align=”center” size=”3″ quote=”For some reason, this detail about their life—that they do not have a permanent home—instantly becomes the characteristic by which we define their entire existence. Yet each time I met an individual who is homeless and heard their story, I realized we are all only one or two steps away from being homeless.” parallax=”off” direction=”left”]

Every day, whether we like to admit it or not, we all engage in a battle between hope and hopelessness. Fortunately for many of us, hope usually wins. We are surrounded by friends and family who encourage us as well as promising opportunities and goals that motivate us and allow us to believe we are working towards a better future.

Hope

We terrified our friends and family with this project. We knew this would scare them and we wanted to harness that fear for the benefit of others by raising the funds to get us home and donate it to the shelter. However, what if we looked at everyone on the streets as a friend or family member? What if we reacted to their homelessness with the same urgency and panic as our friends and family did for us? If the two of us were able to raise $3,000 in a weekend, can you imagine what could happen with just a little shift in our collective mentality?

Maybe one day we’ll be able to bring everyone home.