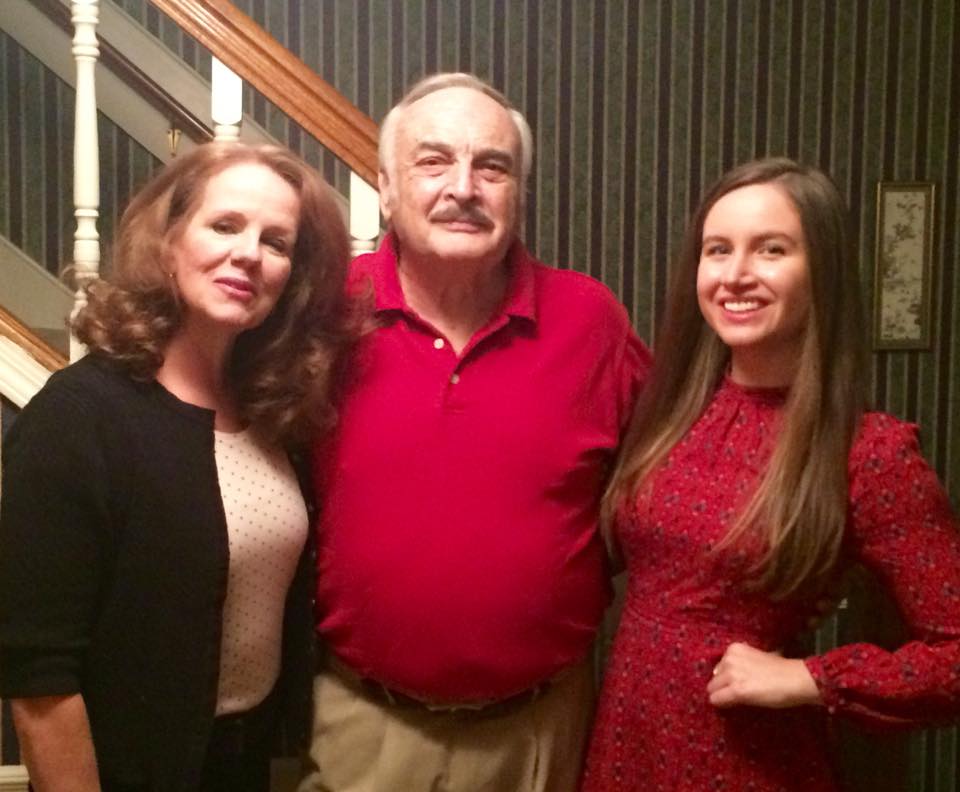

For many years in the Lexington community the name Joe Ferrell and theatre have been synonymous. Joe has helmed many productions, ranging from Shakespeare to the modern classics, under a myriad of venues. The deep and abiding love Joe has for good theatre and artistic process is rivaled only by his love for family and the friendships he’s developed over a five-decade career. His wife, Sheila Omer Ferrell, is the Executive Director of the Blue Grass Trust for Historic Preservation in Lexington. Their daughter, Hannah, has grown up in Lexington after her parents settled down here to start a family in the 80s. Joe speaks candidly with UnderMain contributor Charles Sebastian about family, theatre, and his newest project as director, the Woodford Theatre’s current production, Of Mice and Men.

UM: Let me start by saying I’m sorry the snow affected opening night for Of Mice and Men. The show’s slated to run three weeks, correct?

JF: Yes, the show runs Fridays, Saturdays, and Sundays at Woodford until February 7.

UM: How did the show take shape?

JF: I had directed the show at Actor’s Guild in the late 90s. I hadn’t directed it up to that point. I had played Lennie doing some scene work for some of my graduate courses. It’s a remarkable piece of work. I like to do so many different kinds of things as a director. That period of time was so difficult for people, especially in the mid-West and West Coast regions. There was a lot of difficulty just in staying alive.

UM: We’re talking 1930s, when Steinbeck was writing.

JF: Yes. Steinbeck talks so strongly in the play about loneliness and the difficulty of living. The loneliness, I feel, is a central theme of the work. The need for individuals to not just relate to one another, but to really be connected. The guys in the play were almost envious of their relationship between George and Lennie.

UM: Even though it is rocky and unpredictable at times.

JF: The relationship between the two has all of the ins and outs, ups and downs. It deals with, in 1936 terms, what was then called the American Dream. The two characters wanted to follow their own muse and not be under the thumb of a boss. The inherent failure of that for the characters is heart-breaking.

UM: There is something universal about the relationship, isn’t there?

JF: George and Lennie have their dream about where they’re going and what they’re trying to do, but Lennie’s unpredictable and essentially is just interested in petting things. George can’t let Curly just run off and assassinate Lennie, so he decides to put Lennie out of his misery.

UM: A mercy killing.

JF: Yes. There’s just no way George can protect Lennie after a time.

UM: There’s a sense of it being better being put out of your misery by someone you know, someone who cares about you, instead of some random executioner.

JF: And that makes for a very sad and touching situation.

UM: A lesser of two evils situation.

JF: Yes. Hard decisions. Life was a lot harder in Dust Bowl, 1930s America.

UM: It’s interesting that the play focuses so much on male relationships, though there is the one female character.

JF: There’s only one woman in the play, and she’s constantly referred to as the tart.

UM: Courtney Waltermire plays Curly’s wife.

JF: Yes. Courtney has the kinds of things that all of us who try to do good theatre are born with. Instincts. A lot of this is an openness to trying new things. Courtney could have a career, if that’s what she wanted. Curly’s wife is portrayed as a lot of women were at that time: not particularly smart and longing for somebody to talk to; she has her own version of the American Dream. She feels pretty and someone from Hollywood told her she was pretty, so she’s concocted her own dream of being found.

UM: The old Veronica Lake, discovered in a bar deal.

JF: Right. She’s sorry that she got married to Curly, and Curly isn’t a very nice guy.

UM: She’s looking to escape.

JF: All the men are living hand-to-mouth, living in a bunkhouse. Curly is one of the smallest of the men; one could say he has short man’s syndrome. He’s always uptight.

UM: Is research and dramaturgy a big deal on a play like this, one that has seen so many performances and is so well-known?

JF: Absolutely. I research the play and we have a rehearsal period, just talking about the play, including its historical significance. I’m always encouraging the actors to research and know the period and place on their own. Two people could come up with two different viewpoints on what the play is and how to manage it.Â

UM: You’ve worked with many of the actors in this production often over the years. Walter Tunis, Paul Thomas, Jeff Sherr, Kevin Hardesty. Does having a history with actors make the process easier?

JF: Absolutely. Trust is such a big issue with being able to play and explore. If you already have a relationship, it makes things move faster and makes getting to some truth much easier. Knowing a lot of these actors helps so much with trust. You have a good idea of where they can go. It doesn’t have to start from the ground up. You know where you are and how to work. You have a good idea of how they can move through process.

UM: How did you come to Lexington theatre, Joe? You’re originally from out west, right?

JF: I was born and raised in Montana and went to the University of Montana. I went on a football/academic scholarship and I came out of a town where all you did was play sports. The University of Montana was not all that big, but it had so many courses and areas for a kid like myself. No one in my family had been to college. I had an advisor in the English Department named Walter King, who was a Shakespeare scholar. I became an English major and Shakespeare was my focus then, with a minor in speech. We were on a quarter system, and the last quarter I had a speech teacher ask me to be in a play he was doing for the Theatre Department. I absolutely loved the experience and I felt like doors had been closed all my life and now they were somehow opened. I intuitively knew this was what I wanted to do with my life. I was sent to Korea during Viet Nam and made arrangements when I got back to go to do Masters work in Theatre; I saw the opportunity to plunge in and get involved as much as I wanted to. I hadn’t had that kind of experience or drive for anything up to that point. I had been in a class play in high school, but it was nothing compared to the experience that came later. I feel overall I’ve been very lucky with the course my life has taken.

UM: What prompted the move to this area?

JF: I came to Kentucky when I was in the first year of my doctoral program at the University of Iowa. I finished the doctorate at Indiana, as I wasn’t that happy with the program in Iowa. Georgetown College hired me. This was around 1971. They had an old theatre where the administration building is now. The Falling Springs Recreation Center. They had what were called “resistance dimmers†in the old theatre then. Sparks would fly out when you used them. Dangerous.

UM: Was the program progressive at the time?

JF: They had a small theatre curriculum at the time and wanted to expand. We developed a lot of great productions over those years. The kids who came were smart and ambitious. Some went on to do film, television, Broadway. J.C. Montgomery, who’s done a lot of Broadway and film work at this point, came out of that time.

UM: When did you make the transition to teaching at UK?

JF: I came to work at UK around 1979-80 from Georgetown, which gave me the opportunity to focus on acting and directing. I was doing a lot of other stuff at Georgetown. I was the only full time theatre guy at UK. It was my time to learn and develop ways of doing things that were essential. I didn’t have people looking over my shoulder and telling me I was doing everything wrong. It was good to be able to spend time at UK.Â

UM: You were at UK for awhile.

JF: Yes. Then, around 1985, Sheila and I married and we went to New York for 5 or so years and I did a lot of off and off-off Broadway. I loved New York and going to the shows. I finally looked at where we were and what we were doing, and we thought the thing to do was come back here, as we wanted to have a baby.

UM: Your daughter, Hannah.

JF: Yes. We thought this would be a better location for family.

UM: That was around the time I met you.

JF: I got a call from the people in Lexington. They were asking me to come and do Shakespeare in the Park.

UM: 1989. You directed King Lear. My first show with you. Shakespeare in the Park at Woodland. Fred Foster as Lear. Joe Gatton. Roger Leasor.

JF: That was the first show I did after we moved back.

UM: Were you able to plug back into UK when you returned?

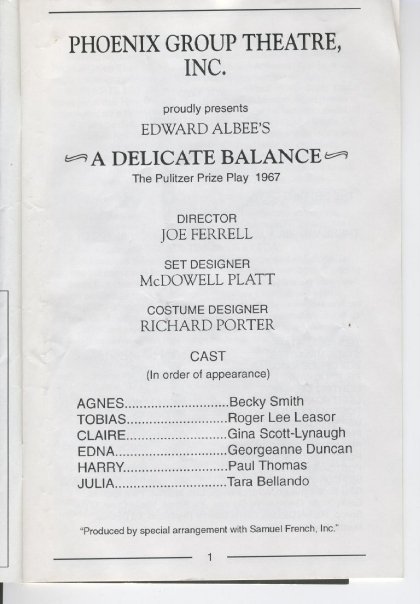

JF: Actually, Fort Knox had just built a huge program. Not many people know this, but there are some posts around the country that have Department of Defense Education Activities, and Fort Knox was one of them. Sheila and I were doing theatre in Louisville around this time, and she was also offered a job in the Fort Knox area. Later, somewhere in the 90s, I started the Phoenix Group Theatre with Kevin Hardesty, Sheila, Joe Gatton, Walter Tunis, and others at the downtown library. Sheila was pregnant with Hannah.Â

UM: You continued at Fort Knox for quite some time?

JF: Yes. I retired from Fort Knox around 2008 and essentially have been doing what I want to do – Woodford Theatre and other projects.

UM: Do you try to stay current with newer theatre trends? Â

JF: If you’re going to do this stuff, you have to be looking at what’s out there. Examine what’s going on in different theatre scenes.

UM: But do things change a great deal overall?

JF: As a director, I’m one who wants to explore, instead of coming in and just blocking it out. I believe just line interpretation winds up not coming across well. Creating a safe space to explore allows actors to build and be fearless when they see a new way of doing it.

UM: Do you find that shows that keep coming around, like Of Mice and Men, for instance, have a universality absent in many pieces?

JF: One of the things I’ve always liked about a good play and the people who write the good ones, is that the speeches are all words we recognize, but written in a very special way: the language in the play is created by dialogues and speeches that are designed to take you in a certain direction. We can have a random conversation any given day, but in a good play, the world is being built by these conversations.

UM: Are you pretty much keeping the same schedule you always have?

JF: I did three plays last years and Mice has been the only one this year. I would like to see something spring to life in Lexington again. Athens West could be the answer. It’s challenging being an Equity theatre, so it’s going to be great to see where they go. I loved teaching in college and loved teaching all of the stuff that I had learned. We have lots of serious theatre-goers who see what’s up on stage. I sometimes worry about where our audiences are going.

UM: Are you referring to the “dumbing down†that’s been happening gradually in the arts in general?

JF: Yes. Things are just different today. So many of the plays remain relevant, but it seems like audiences respond differently today to some things.

UM: Are there certain works you look to as seminal or influential on your life and career, Joe?

JF: The Empty Space by Peter Brook comes to mind. Uta Hagen’s work and a lot of the stuff that came out of the Group Theatre. Clurman. The Stanislavski stuff that eventually paved the way for the Actor’s Studio. Many books have been written on that, of course. A lot of those people wound up turning theatre on its edge.

UM: Roughly a hundred years ago. The “Russian Invasion.”

JF: Right. The end of the 1800s was so overblown in terms of acting.

UM: You’re speaking of the Declamatory style?

JF: Primarily.

UM: Nowadays you just see it done for laughs, just for the sake of being stodgy.

JF: Getting past that and to a deeper truth makes for much better work.

UM: Are you excited by certain playwrights? Are there plays you would like to do that you haven’t yet?

JF: Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? was astonishing for its language at the time. Of course, that’s been awhile ago now. A Winter’s Tale would be interesting, and doesn’t get played often. Neil Simon hasn’t been done as much here as I would like to see. Williams is important. I’ve done Glass Menagerie three times, but that material can always be revisited. O’Neill. Long Day’s Journey into Night. The trend for heavier and longer plays doesn’t seem to be too much on the scene of late, though. It was wonderful we were able to do Venus and Fur at the Farish Theatre, through Balagula. That was one I had wanted to do for awhile.

UM: The theatre for you and the people you work with: it all seems to have a very family feel to it.

JF: You come out of these projects making close friends. Ultimately, good plays are about the relationships that drive us in life. Any of the good plays show how people interact, betray one another, love each other. There’s always the standard conflict stuff, that should be in any good play. I’m as fascinated today by what we can create onstage as I was all those years ago when I started. It’s just amazing what comes out of the rehearsals and what you wind up with as a final product. It affects people in so many ways and I’m affected by it.

UM: Sounds like it’s really about people for you.

JF: The important thing for me is always the people. Designers, actors, all of the making-of process, with so many wonderful talents: that’s what really drives me.

Please visit either of the following sites for tickets or more info on Of Mice and Men: