“All I ever really want to know is how other people are making it through life – where do they put their body, hour by hour, and how do they cope inside of it.”

—Miranda July

“Where does the pain live in your body? Your disappointments? The things you’re too ashamed to name? And your joys, hopes and longings – where do they live?”

—The Rev. Adam Bucko

I.

It startles me how much the painting recalls the dream I had last night, the one where I am being pursued and trying to run, only I can’t get my legs to move, can’t will any kind of forward motion. And the woman on the canvas, naked and warm and fleshy in apricot and ochre, stretches her arms out alongside her, pulling back with a mighty effort as she moves through this dense fog of a landscape, this otherworldly vista. Like me in my dream, her legs seem to be constrained below her knees, engulfed by strokes of midnight blues and blacks that feel weighted and heavy despite the large swaths of white, icy teal and robin’s egg blue that color the canvas. Small marks of red-orange paint sear through the turbulence that surrounds her and mark her skin as she stares out at a distance far beyond us, an unknowable place.

The piece, Tensile/Release, is a 2020 painting by Yvonne Petkus that typifies much of the artist’s work over the past decade. They are variations on a theme in which a figure, often alone, often unclothed, moves through an ethereal expanse of brushstrokes in a palette that recalls the writhing greys and blues of the sea in its darker and more mysterious manifestations. Most often working in oil on canvas or board, Yvonne tends to favor square ratios for her pieces, which creates a subtly voyeuristic effect: in paintings that are so dominated by the physical landscape, her square frame focuses the attention on the figure, on the intense psychological landscape that lies within.

“My work has always been about what we carry in our bodies, the residues of trauma and abuse that we carry,” she says. “Not the hit or the blow or the psychological abuse in the moment, but how it feels ten years later, 15 years later, 30 years later. And the way I paint is about finding that – finding what emerges in each scenario from that sense of what we carry.”

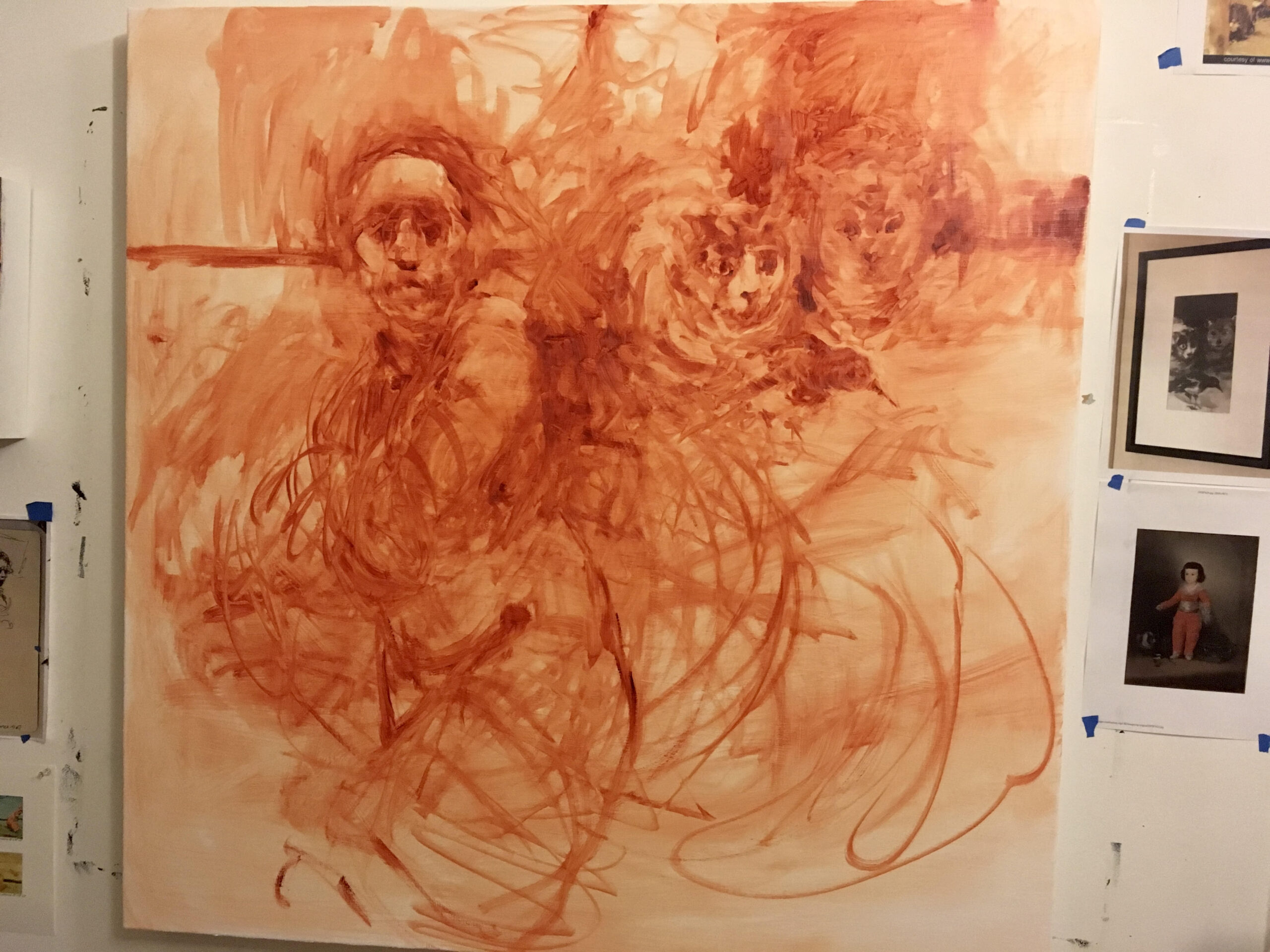

Yvonne describes herself as a process painter and an incremental painter, drawing from many different inputs and experiences and working on multiple pieces at a time, working and reworking canvases with each one informing the others. She often takes months to complete a work; she sometimes alters a piece once it comes back from a gallery. Each begins as an underpainting that responds dynamically to the surface and allows her to find the initial gestures and movements that are influenced by her other works. These will naturally evolve as she adds layers of paint; visual references and cues in the underpainting may become entirely obscured or hidden by the time the work is finished (if such a thing is ever really possible).

What follows is a process of adding and subtracting layers and images, working something in, taking something out, adding a figure, subtracting an element. Painting, for Yvonne, is “a medium of thought and invention.” And if an image comes too easily or is too recognizable, she says, she has to break it and find the question about it: “It’s very much about this intense questioning, this directed struggle across the surface, and working it back and forth until it congeals and finds its presence or looks back at me and is itself.” Much like the figures and the landscapes she paints, Yvonne’s work has the sense that it’s always becoming, a restlessness that resists any final state.

“Her paintings are intense, which is exactly like her. Intense, layered, but there’s also a warmth to them, and a desire for connection and conversation,” a colleague tells me. Kristina Arnold heads the Department of Art at Western Kentucky University (WKU) in Bowling Green where Yvonne has taught for two decades, and has worked with her as a teacher and an artist since 2005. Kristina reconsiders her comment. “Warmth may be too light of a word. It’s intense and it’s searching, in that very human way that we all do. It’s a serious and intentional quest to connect with the other.”

II.

Yvonne and I connect over email and Zoom. It is late autumn 2020 and the pandemic threat has drawn everyone back inside, heightened precautions and anxieties. Yvonne has been teaching at the university in-person and virtually, ten hours on Mondays and Wednesdays, less on Tuesdays and Thursdays. Evenings are reserved for her personal practice. A nocturnal animal, she works deep into the night, when the clamoring of the day’s emails and deadlines and committee meetings fall quiet and time seems to stand still for her. It is a time, she says, when she can breathe and be present.

In the window of my laptop’s video conferencing app, all I can glimpse of this world is a small frame in which there is a figure – the artist – amid a swirling mass of oil on canvas. Yvonne is affable and open; she tells me about her formative childhood years frequenting the museums in New York, standing in awe in front of Anselm Kiefer works at MOMA and being drawn again and again to Rembrandt’s self-portrait at The Frick. She talks about her parents, both teachers, and her close but complicated relationship with her father, the son of Polish and Lithuanian immigrants, a strong, self-made man who served as Dean of Education at a college in New Jersey, where she was raised. He was a huge presence in her life, she says, and his death this past year was a tremendous loss.

Yvonne is engaging and enthusiastic, especially when she talks about her students and teaching, a practice that invigorates her personal work. Her methodologies are largely influenced by her time at Camberwell College of Arts in London, where she studied for a year as an undergraduate. At the time, she says, the British system of art education was focused on mentorship and self-motivation, and encouraged students to seek out feedback and instruction on their own.

In much the same way, Yvonne wants her students to be self-directed. “The way I teach isn’t just showing someone how to do something, but also how to think, how to process, how to look for possibilities over outcomes. And for me that way of helping others find their expressive means and a sustainable practice is extremely energizing. I feel so connected to my students. There’s a lot of time involved, but it’s also very energizing for my work.” Yvonne was too self-effacing to mention it, but I later learned she had recently been recognized as a University Distinguished Professor at WKU, the highest honor bestowed by the institution.

I thank her for her time, and we agree to meet at her studio the weekend before Thanksgiving. Later, she emails me and apologizes but asks if we could reschedule for the following week – after realizing she would have an entire week free from her teaching obligations, she wanted to spend the time hunkered down in her studio. Already, I recognize this intensity of focus that was evident even in our first conversation, a relentless searching through her work, combined with a tendency to seek out the most extreme conditions in order to discover something about herself, and about us as human beings, about how we relate to each other and how we understand our place in the world.

“One of the things that’s most impressive about her body of work is how persistent it is,” Kristina later told me. “And how persistent she is. Some of that is through her prolificness. But there is also a persistence of discovery.”

III.

The island country of Iceland is the most sparsely populated in Europe; it is dominated by a vast and wild terrain of mountains and glaciers, rivers, volcanoes and lava fields. The weather can alternate between raging hailstorms and blinding sunshine many times during the course of a single day and roads often close abruptly (there are, indeed, multiple apps for that). Its capital, Reykjavík, is characterized by extreme lengths of day and night, and its coastal location makes it prone to gale-force winds. About 75 miles to the north, the Snæfellsnes Peninsula is even more remote, providing the setting for 13th century Icelandic sagas as well as Jules Verne’s science-fiction novel Journey to the Center of the Earth. This is where Yvonne wanted to spend her 2016 sabbatical.

This alone, some might find formidable. But Yvonne deliberately chose to go to Iceland in February and March, when the seasons shift from one extreme to another, from near-total darkness into almost ceaseless light. And then to use that time not just to paint, but to train for a marathon. And not just any marathon, but the Boston Marathon, one of the hardest to qualify for and also the most prestigious. And to do it barefoot. (Yielding slightly to the island’s dangerous terrain and weather, Yvonne did wear a minimalist sole while adhering to the principles of barefoot running. But still.)

“I think that as an artist and a person, I make things as hard as possible on myself,” she tells me, in case this fact had been lost on her interviewer. And yet beneath the dogged rigorousness of her pursuits, there exists an abiding beauty and heartfelt intention, an aching desire to discover what it means to be human and to be vulnerable, to feel what it means to be at the mercy of forces greater than yourself.

“Going to Iceland and training for a marathon in those conditions, it was intense,” she concedes. “But I intentionally did that because it affected how I relate to nature. I got to feel and experience struggle within a landscape. To be running through the national park and have people tell me that someone died there a year ago because of the winds. You were constantly aware of your own mortality and your vulnerability, but also your strength.”

The dramatic landscapes fed her work in other ways as well, the water and mountains and fog familiar to her earlier work now appearing in different forms and tones. Her palette expanded to include more brilliant whites and lighter teals and sky blues, her brushstrokes became broader and her figures smaller, sometimes to the point of nearly disappearing into the landscape altogether. And her canvases opened up, not only revealing more white space but also allowing her to break from the confines of the square and sprawl out in extravagant horizontal expanses.

In preparation for her trip, Yvonne had begun painting on plastic, knowing she couldn’t ship her canvases across the Atlantic and back again. The plastic enabled her to work larger and lighter (both in the sense that it weighed less and that it allowed more light to come through the images), empowering her to capture a land she describes as “extreme and subtle at the same time.” The work conveys a sense of terror and ecstasy in equal measure, that realization of one’s smallness and insignificance within the vast landscape of time and nature.

On the island, Yvonne sat each day and watched the fishing boats as they sailed back and forth across the horizon, feeling an unspoken kinship with these workers as they went about their daily routines. When she exhibited her work in a solo show at the end of her residency, she was delighted to discover that some of the visitors were those very same people who had been aboard the boats. “We see our Iceland but in a way we’ve never seen it before,” they told her. They recognized and understood, she says.

“I don’t think she intentionally makes work thinking about the viewer in the back of her brain,” Kristina tells me. “She goes into her place and makes work. But at some level she’s very conscious of making that connection with an audience, even if that’s just one person to pull out and have a conversation with through her work.”

IV.

When she returned from Iceland, Yvonne had the opportunity to apply for a fellowship in Bosnia, an experience she had been seeking in order to understand more fully the struggle her father’s mother had endured as a young girl living in Poland during the early part of the last century – running from enemy forces, hiding in the woods, escaping an abusive first husband.

In 2017, Yvonne became one of eight WKU faculty members selected to participate in the Zuheir Sofia Endowed International Faculty Seminar (ZSEIFS) in Bosnia and Herzegovina. In the six months leading up to their travel, Yvonne and her fellows engaged on an intensive study of the country, sharing learnings across the various disciplines they represented. Yvonne’s expertise in visual art was augmented with briefings by professors in history, law, journalism, folk studies, and social work, giving her a rich and multi-faceted understanding of the region before she even arrived.

Once there, the group met with everyone from representatives from the Dayton Accords and the Missing Persons Commission to concentration camp survivors and people working within the schools to foster resolution. All the while, Yvonne was also doing her own research, visiting museums and meeting with artists and curators. She saw her grandmother everywhere, she says: in the cheekbones of the Bosnians she spoke with, in the photographs in museums, in the bones and the skin of the people she sketched.

“In Bosnia, it became about this other type of awareness of the body. You could feel that idea of what we carry in our bodies,” she says. “People were so generous and immediate with you in terms of sharing experiences, sharing coffee, sharing everything. It was so much about human-to-human interaction – about sharing and understanding and empathy.”

Other figures began to appear in her paintings – clothed forms locked in struggle, ominous shadows, disembodied faces. Canvases resumed their tighter ratios as if closing in on the figures; the return to a darker palette took on the weightier burden of the subject matter. Faces now appeared in close-up, startling and disarming as they filled the frame, displaying an abjectness at the same time they almost dared the viewer to ignore them, ignore their suffering. And the naked woman’s gestures took on a new futility, her attempt to run becoming a seemingly impossible maneuver through the swirling mass of dark brushstrokes that now swallowed her above her knees, above her hips, above her chest.

“Everywhere I went, I sketched,” Yvonne says. “As a runner, I felt like I understood the gesture of a run and I’ve used it in my paintings for many years. But then when I saw these photographs of people dashing across the street, knowing that there were snipers that could kill them – and just did kill that person lying there in the street – there became this existential weight to the gesture of the run that I’ve been working with ever since, to try to understand.”

Back at home, Yvonne’s own work and her curatorial work (an exhibition of 12 artists of Bosnian and Balkan origin) was shown as part of WKU’s International Year Of… program, of which the 2017 focus was Bosnia. Bowling Green is home to nearly 5,000 Bosnians, many of them refugees from the war. One of them, a woman, approached Yvonne at the show, crying and telling her, “My neighbors knew where I was from, but this is the first time they understand.”

“She felt seen for the first time,” Yvonne says. “That’s as meaningful to me as getting into any Biennale.”

V.

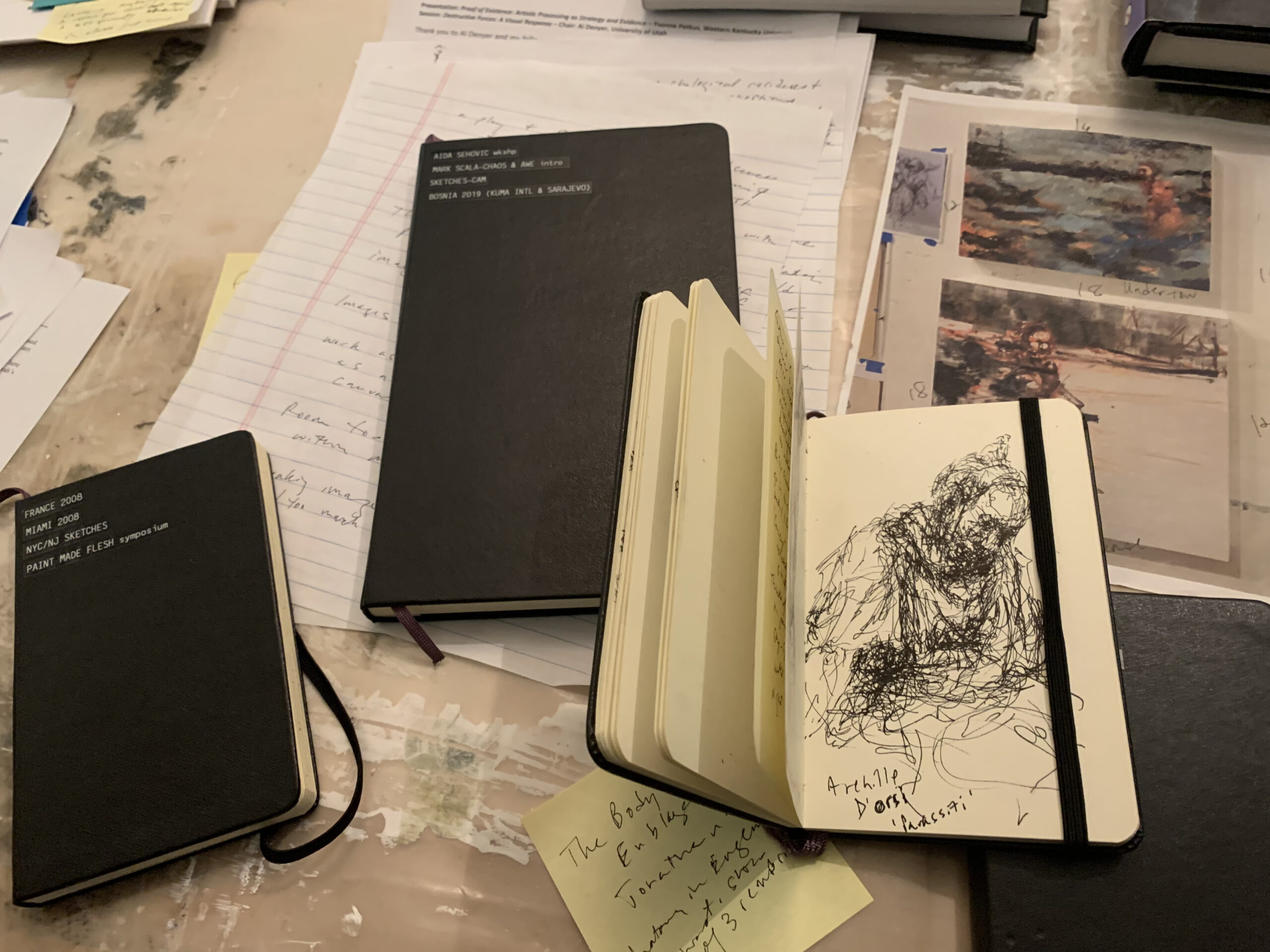

One cold but bright Saturday in early December, a curator friend and I meet Yvonne at her home and climb the steep wooden steps to her attic studio, a comfortably claustrophobic space where shades are drawn to the outside world. Walls are covered with canvases, boards, sketches and photocopies. Tables are littered with paints and brushes and books, large envelopes of photos and clippings, black Moleskine sketchbooks with neatly printed labels that identify the contents as “BOSNIA 2019 (KUMA INTL & SARAJEVO)” or “AIDA SEHOVIC – wkshp.” And nestled amidst it all is one small, smooth, dark rock given to her by a fisherman in Iceland.

Yvonne is generous with her time, speaks passionately not only about her work, but also about her students, the nurturing artistic community in Bowling Green, and a book she has been reading called The University of Disaster. Published in conjunction with the Bosnia and Herzegovina pavilion at the 2017 Venice Biennale, the essays in the book center on the concept of a larger human project, an idea that Yvonne says gives her a sense of relief:

“Every time I paint I have this intense, almost overwhelming, desire to do it all, to say it all. One writer talks specifically about artwork as sketches of your partial extent of the larger measure. That I can offer a partial extent to this larger measure not only feels like, okay, I can handle that, but it also feels like I’m connected. I’m not just in here doing my own thing, I’m connecting to this larger project. And through the Bosnian work and people and connections and dialogs I’ve been able to have since 2017, I feel like it’s true.”

My friend and I had packed sandwiches for lunch, knowing restaurants would be closed due to COVID restrictions, and Yvonne graciously offers us the table on her front porch and brings us mugs of hot coffee. The three of us sit distanced and chat casually about museums and shows, holiday plans – and, of course, the pandemic, this collective psychological trauma that we were all experiencing to some degree, that will leave its residue long after a new normal has evolved. An orange tabby cat wanders over and jumps on my lap, sniffing the smoked salmon on my sandwich. Her tiny, sharp teeth nip at my hand, leaving little marks on my skin that I will carry with me back to Louisville, the faint physical residue of this sunny afternoon.

The next day I awaken to an email from Yvonne, who has realized I haven’t seen any of her work in the underpainting stage. She attaches a photo, a painting she had started just after her father had passed away; in this first layer she deliberately included two cats and a bird, as a memory of him and as a way of working through the loss. They were visual cues of happier days, a reference to her ink rendition of Goya’s Manuel Osorio Manrique de Zuniga that her father had kept on his wall for years. Many layers and months later, the work became Tensile/Release, and in its final stage, the animals are visible in only the most abstract way, in the way that only we know our own residues of trauma and loss, these secret joys and longings we carry with us.

Note:

Yvonne’s research was supported through the SÍM Artist Residency Program in Reykjavík and by the Hvítahús Artist Residency on the Snæfellsnes Peninsula, as well as through grants and awards from the WKU Office of International Programs, Potter College of Arts and Letters, and a 2019 Great Meadows Foundation Artist Professional Development Grant.