For some of us, a certain kind of artmaking starts in early childhood, trying on different outfits in front of a mirror. Sometimes the clothes are our own. Sometimes they belong to our older siblings or our mothers or fathers or both; wearing these magical, perhaps forbidden garments (along with wigs, paper hats, fake mustaches, and the like) allows us to imagine ourselves in any number of disguises and personas, pasts and futures. We transform and shape-shift because it’s our nature. We contain multitudes, as the poet said, and sooner or later, we manifest those multitudes by becoming performers or writers.

Or visual artists. I don’t know whether Cynthia Norton or Kiah Celeste – both Kentucky artists with solo exhibitions at Louisville’s KMAC Museum through November 7 – ever played dress-up in front of a mirror as children, but it wouldn’t be surprising if they did. Norton’s “Mystical Heart†and Celeste’s “Before It Falls Apart†play with the idea of metamorphosis, and with delineating and revealing different aspects of the self, in ways that seem closely related to the imaginative self-explorations of childhood. I say play in at least two senses of the term, as both shows feel distinctly theatrical, performances of a sort, and also like products of fun, fruitful improvisation, however serious the end result. Viewing these shows, it’s easy to get caught up in the spirit of creative play, even when, as is its wont, it turns dark.

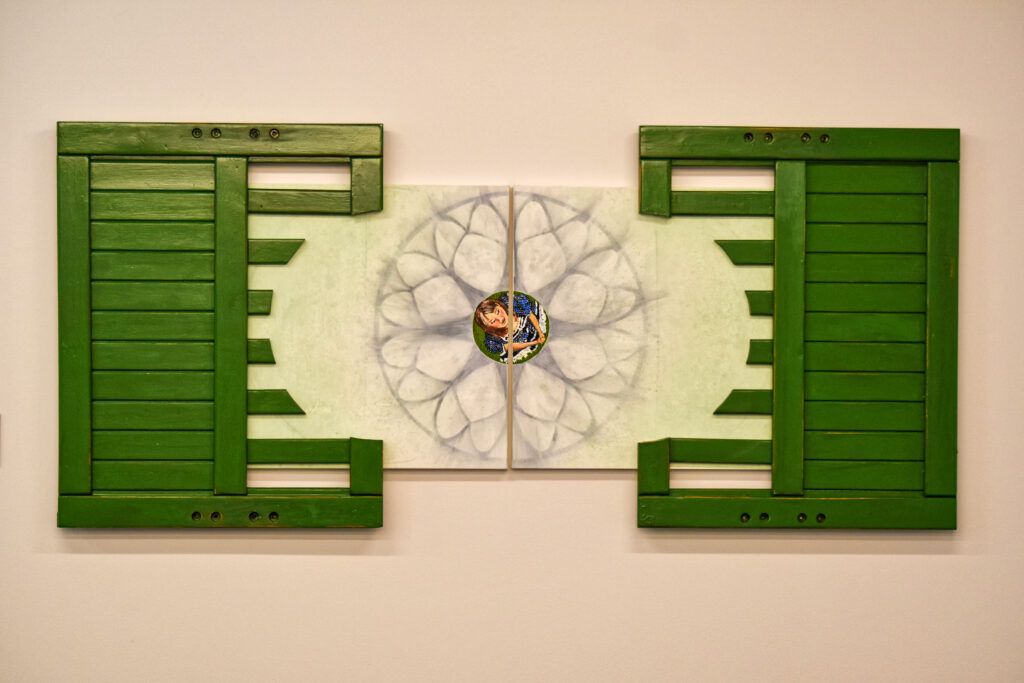

This is particularly true of “Mystical Heart,†a group of paintings nestled inside transmogrified antique bed frames, which conjure both the 19th and early 20th centuries and the Land of Nod. All of the paintings feature different sides and iterations of Norton’s alter ego, Ninnie Noises Nonesuch, the young Southern character she has played for years as a performance artist. For viewers unfamiliar with that body of work, the wall texts firmly situate Norton’s visual art here as an outgrowth of her theatrical work, which in turn is heavily influenced by the iconoclastic French intellectual, mystic, writer, film actor, and theater director Antonin Artaud (1896-1948). “Mystical Heart†turns out to be visual art grounded in performance art that is itself grounded in avant-garde art theory from a world away and a century ago: an art-historical rabbit hole with no end in sight.

Better to concentrate, I think, on what’s in front of us in the gallery, which is to say, the pieces themselves. Painted in a knowing folk-art style, they are not without clues as to their meaning – most of their titles include fairly bald thematic labels, enclosed in parentheses, such as “Hope,†“Lyricism,†and “Touch†– and yet they often remain as enigmatic as the dreams dreamed in the beds that surround them. They’re full of symbols that can feel like hermetically personal references to concepts and events that only the artist herself can know. The museum’s supplemental materials use the words narrative and storytelling in relation to these works, but the stories are lightly, fleetingly implied, like stills from the middle of a movie whose beginning and end are unknown; instead, they invite the viewer to fill in the blanks. How did Ninnie arrive at this or that apparently critical juncture? What happens next? It’s up to the viewer to decide.

In “Ninnie Root (Lyricism),†which feels like the show’s centerpiece, Ninnie appears as a young girl in a yellow dress and petticoats on what might be a riverbank. (Her outfit suggests a bygone American South, but it also emits a certain Alice in Wonderland vibe; there’s even, maybe, a rabbit, more about which later.) The ground at her feet fairly writhes with gnarled, mossy, presumably slippery tree roots of distinctly serpentine character. The fact that Norton is originally from Athens, Kentucky, at the far eastern edge of Fayette County, may contribute to your understanding of the scene. Her arm extended out and up, Ninnie bears a lotus blossom, offering it up to a red orb (a balloon, maybe, although there’s no tethering string) bearing the name Hugo. You learn on KMAC’s website, if you choose to hunt for it, that this refers to Hugo Ball (1886-1927), a German writer, social critic, and co-founder of the nihilistic Dada art movement of the early 20th century. You can therefore read the painting as a moment of dedication and deliverance, a dreamy Southerner committing herself to an eccentric and, yes, lyrical life in pursuit of High Art with European roots.

Elsewhere, Ninnie perches on another of those mossy tree limbs, this time blindfolded and suspended precariously over the river: a portrait, perhaps, of the artist as a young mystic, shutting out the sight of her immediate surroundings in search of interior landscapes more to her liking. “Ninnie Naga (Horn of Valor),†featuring our protagonist as a mature woman sprawled (floating? drowning?) on her back in what might be a swimming pool shaped like one of Jeff Koons’ bunny sculptures, may be at once the show’s wittiest piece and its scariest. Or perhaps that honor goes to “Ninnie Knot,†a sort of Rorschach image in which Ninnie and her reflection can morph, if you look at it long enough, into another rabbit, this one distinctly sinister.

“Mystical Heart†is at its most moving (and most explicitly art-historical) in “Ninnie Noche (Mask Transfixed),†an homage to René Magritte’s surreal painting “Time Transfixed†(1938), which Norton would have seen at the Art Institute of Chicago, whose school she attended. Instead of Magritte’s locomotive, which appears to be charging out of a fireplace flue beneath a mantel and clock, Norton shows us the other end of the train: a caboose with Ninnie standing at its rail, her face obscured by what seems to be a banjo. The train, it’s easy to imagine, is leaving the station that is Norton’s past. Ninnie is receding from our view, moving away from us (and from Norton herself) in both space and time, but taking with her a symbol of the Bluegrass, using it as a mask and a shield.

***

Although it lacks the emotional charge and the sheer, vivid weirdness of Norton’s work, Celeste’s “Before It Falls Apart†has its own virtues. Lighter, funnier, and more impersonal than “Mystical Heart,†Celeste’s exhibit uses photography and outdated industrial materials in a playful exploration of what’s possible when you give an enterprising and resourceful artist a platform to experiment in public.

It’s also generally more straightforward in its artistic aims than the Norton show, not to mention a good deal less dependent on wall texts and other supplementary contextual framing; what you see – the work itself – is what you get and, mostly, all you need. Its ethos is workmanlike, transparent, and democratic, qualities underlined by Celeste’s eschewing expensive art supplies in favor of cheap and/or salvaged products that otherwise would end up in landfills: old exercise balls, rolls of fiberglass, pipes made of plastic or corroded metal, vinyl bags filled with sand.

The show is divided into two parts, one focusing on sculpture, the other on large black-and-white “Contingent Sculpture†photographs showing the artist herself having some moderately interesting fun with things like golf balls, which she holds between her arms and her sides (or between her legs), and airshaft covers, to which she clings in a way that suggests hybrid creatures, part human, part machine. The best of the “Contingent Sculpture” pictures, hands down, is the one in which the artist’s lower extremities seem to have transformed into something like the coiled tentacles of a squid or octopus. Ovid would have recognized and approved of this striking image, as would the surrealists from Dalà to Remedios Varo.

Celeste’s sculpture, in the adjacent gallery, is more assured and more consistently inventive. Her precarious stacking and squeezing of elements, the constant collisions of hard and soft and the resulting distortions, is quietly virtuosic. And the humanoid character of several pieces – including “In Good Company,†which suggests a tightly corseted mother and her two similarly restrained children, and “Recess,†which calls to mind drooping, exhausted human bodies – makes me think that the show’s title has at least a double meaning. The word It refers, maybe, not only to the materials Celeste is using but also to the body itself: hers, yours, ours. We all end up in landfills of one kind or another, sooner or later. The question is which of our possible selves we become, between now and then.

Top image: Cynthia Norton, Mossy Limb (Hope), 2017, oil on canvas, repurposed bed frame. Photo by Kevin Nance.