Three current exhibitions in Louisville, Kentucky offer an opportunity to assess a southern aesthetic in the visual arts. Two of the three shows define their topics narrowly, providing a specific critical viewpoint. The third invites something altogether different.

“Provoking the Uncanny: Ralph Eugene Meatyard”  (Schneider Hall Galleries, University of Louisville, through August 14th), curated by Hunter Kissel, zeroes in on Freudian implications of the Lexington photographer’s use of blurred and prolonged exposures while photographing masks, dolls, as well as child and adolescent models. Meatyard’s inventive Southern Gothic conveys the combination of fright and anxiety Freud believed arose from recognition of imagery associated with traumatic memories of a childhood long suppressed in the subconscious. The psychoanalytic concept of the uncanny provides a fresh critical view of Meatyard’s ability to tap into a hallucinatory merging of reality and fantasy.

Comparably focused is “Southern Elegy: Photographs from the Stephen Reily Collection” (Speed Art Museum through October 14th). Reily assembled a connoisseur’s selection of Louisiana-centric images starting from the premise that “southern photography is often inspired by its own sense of captured memory, self-aware of the losses that underlie the landscape before us as well as target the losses that will transform it once again.†Staving off oblivion is a risky endeavor, but the collection evades the obvious risk of mawkishness, first through the extraordinary quality of the work, and secondly through the selection of photographs which are broadly poetic representations of the South rather than documents. The most affecting photograph in the collection is Sally Mann’s sun-struck shot of the bank of the Tallahatchie River where the murdered body of Emmett Till was heaved into the water. Mann has written that she finds the South “death-haunted, pain-haunted, just haunted, period…I was looking for images of the dead as they are revealed in the land and in its adamant renewal.† “Provoking the Uncanny†and “Southern Elegy” are both tightly conceived, coherent bodies of work that provide excellent complements to their larger counterpart.

In contrast, “Southern Accent: Seeking the American South in Contemporary Art†(also at the Speed Art Museum through October 14th) is a grandly multifarious affair, an exhibition that leads in multiple directions. It promulgates, in its various threads, the argument that the South is in the throes of revolutionary evolution. Yet, the exhibition’s ambitions go beyond simply tracking that rapid change: the mind, the culture, the zeitgeist, the possible personal meanings of “the South,†are addressed through the works of art, the accompanying audio library of southern music, and the 275-page catalogue, which variously includes scholarly essays, artists’ statements, poetry, anecdote, a cultural chronology, a music library, and a reading list. The show broaches “the complex and contested concept of the American South through the lens of contemporary art†in this sweeping (and ultimately affectionate) effort at “enacting and interrogating southern identity.â€

The title “Southern Accent: Seeking the American South in Contemporary Art†is therefore not about a distinguishing twang, but accentuation on a trenchant and consequential moment in American art played out in a particular region of the United States. Time is not a continuum in this show, but a mechanism for looping back to the past – not as the object of a long, fond, lingering look, but as a departure point that posits a more benign future. And unlike earlier regionalisms, the art seldom aims to find the universal in the local, but rather to demarcate and hail its particularities.

The co-curators, Miranda Lash of the Speed Art Museum and Trevor Schoonmaker of the Nasher Art Museum at Duke University, subvert the magisterial authority of the curatorial voice in resetting the parameters of inquiry into American regionalism, and reformulating traditional imagery of southern identity. There is no acoustic guide sequence for touring this exhibition, allowing for individual pathways of discovery. To me, it prompted a train of musings about nature and sense of place, cool and anti-cool, art as witness, speaking truth to power, and finally, the possibility of prototypes for a new sectional iconography.

The introductory work in the exhibition sets the tone for much of what follows: Thornton Dial’s “Monument to the Minds of the Little Negro Steelworkers†is a screen relief as rigorous and formally elegant as any by the late Sir Anthony Caro. A self-taught (or indigenous) artist, Dial arranged wrought iron floral plumes on the screen, adding to this scavenged assemblage plastic flowers, an ax blade, animal bones, glass bottles, tin cans, paint can lids, enamel paint and scraps of cloth. Some of these additions are associated with traditional African-American burial practices and are believed to have protective powers. Dial’s sculpture performs a sacerdotal memorial to the creativity as well as the dangerous lives of African-American steel workers. At Sloss Furnace National Historic Landmark in Birmingham, Alabama, where Dial lived, one learns that black workers had the hottest, most arduous and most dangerous tasks in the foundry. Sloss Furnace is locally believed to be haunted because of the many workers’ deaths during its years of operation (1882-1971).

“Monument to the Minds of the Little Negro Steelworkers,†in aesthetic disguise, conjures up a propitiatory tribute to marginalized mill hands. In the broader context of southern icons, Dial turns on its head the clichéd views of New Orleans’ French Quarter balconies and transforms associations with the conventionally picturesque into a potent argument for the moral intelligence and pertinence of a disparate group of repurposed objects.

Sense of place is not directly addressed in this exhibit but it is continually manifest in the imagery of climate and vegetation. The searing, unforgiving intensity of summer sun and heat is conveyed in Benny Andrews’ fabric collage of a stalwart woman passing a row of workers’ cabins, her black obelisk-shaped shadow competing for attention with the figure herself. Like heat, vegetation is a place marker but there are no grand allées of live oaks festooned with Spanish moss and no genteel borders of azalea. Plant life is mystically profuse in the wonderful pairing of watercolors by Walter Anderson and crayon drawings by Minnie Evans. Jim Roche’s photographs with text and Howard Finster’s tree of life “vision of the angels feed on the fruit of a farren [sic] land†share a vitalist sense of a benevolent plant world. These stand in contrast to the malevolent, inexorable advance of kudzu in photographs by William Christenberry or the eerie algae scum in Jessica Ingram’s forbidding photo of a cypress swamp.

The uses and moods of a pressing natural world find little concordance with depictions of the built environment. Over 50 of the 125 works in the exhibition feature structures of some sort, but outdoor views vastly outnumber interiors. Neighborhood, family and street life vanished: boarded up after Katrina, obstructed by segregation, wealth or ethnic distinctions, or abandoned because of economic shifts, misplaced governmental policies, or migration away from the South.

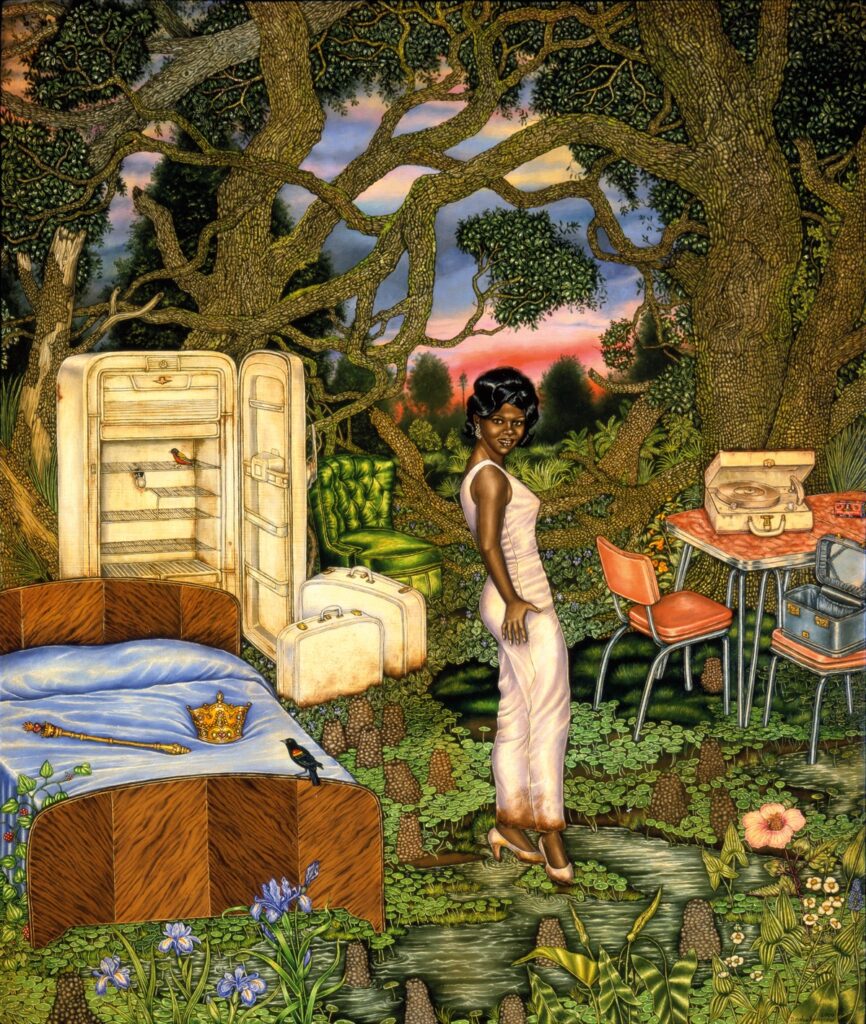

Beverly Buchanan’s miniature cabins made of scrap wood are cenotaphs - tomblike monuments- for generations dispersed from farmland but poignantly and equivocally are also loci of longing for a fixed and familiar home place, however impoverished. Douglas Bourgeois’ ironic interiors-without-walls, as in “American Address,†depict in hallucinogenic detail the unreality of that pining. Curator Trevor Schoonmaker observes “the acts of leaving and coming home seem an integral and commonplace part of southern life.â€

I perceive another sub-theme in the expression of cool and anti-cool. First used by jazz musician Lester Young in the 1940s, “cool†denotes a defiant assertion of individuality, independence, and rebellion. Cool is sartorially resplendent in Barkley Hendricks’s 1971 painting, “Downhome Tasteâ€, and echoes the theme of black masculine empowerment in Blaxploitation films of the same era – downward tilted hat, sunglasses, cigarette, leather jacket and woven belt – costumed as if in a film still. Cool exists on a continual gradient. In Fahamu Pecou’s self-portrait as a high-stepping vaudeville performer, the words CHIT’LIN CIRCUIT celebrate the show people of that segregated tour while an Outkast lyric sprayed across the top of the canvas offers an ironic comment on the circumstances of those performers’ lives. Pecou’s engagement with an obsolete version of cool induces a searching dialogue with historical versions of black male identity.

Cool as a personal style, a way of being in relation to a particular time and place, is deeply interwoven and intrinsic to Southern identities. Hats, headdresses, and hair-dos proclaim the with-it-ness of those depicted as in Willie Birch’s monumental and joyous drawings of the Storyville Stompers Brass Band and Second Line and the Big Nine Social Aid and Pleasure Club. Anti-cool is signaled again and again in the exhibition by hats: helmets, snap-brims, police caps and Klan hoods. Although the concept of cool is historically African-American, the inextricable mix of southern identity and cool go beyond the black-white binary. Diego Camposeco’s portrait of a fifteen-year-old Mexican-American North Carolinian in a flouncy blue gown is one example of how “southerner†now has multiple modifiers beyond African-American or Caucasian. Other ethnicities and sexual orientations manifested in the exhibition include Native American southerner, Afro-Native American southerner, Vietnamese-American southerner and lesbian southerner. Multiple cool southern identities are conjoined in Jeff Whetstone’s portrait of “Caitlin,†a teenage hunter, posed in the woods wearing camouflage, shotgun across her lap, made up with polished fingernails, lipstick, eyeliner and pearl earrings.

Art as witness and speaking truth to power parallel different concepts of self outlined above: there is an implicit revolutionary bias in many of the guises adopted in “Southern Accents†portraits. Of all the adversarial forces to be overcome – hurricanes, economic hardships, prejudices, or, for some, godlessness – racism takes center stage. In terms of visual imagery the archetype is the Civil Rights protests of the last half of the 20th century. Two contrasting marches, seen in Michael Galinsky’s chilling edit of 1987 video footage, “The Day the KKK Came to Town,†and Hank William Thomas’ installation of sixteen photographs on mirrored surfaces of the Bloody Sunday march in 1965, encapsulate curator Lash’s description of “the region’s layered history of racism and oppression.† Speaking truth to power underlies William Cordova’s “Silent Parade: Or the Soul Rebels Band Vs. Robert E. Lee,†a video depicting the jazz troupe’s musical jeer at the New Orleans monument to the Confederate general. (The monument has since been removed).

Finally, there are works in the exhibition that invite (at least theoretically) performance and decoding: set as stage sets, like good drama, they offer if not a healing catharsis, then the extended reflection that follows adept provocation. The struggle against privileged legacies takes many forms. Theaster Gates’ “Soul Food Rickshaw for Collard Greens and Whiskey,†a beautifully crafted pushcart made in part from recycled desk drawers, is a rolling tabernacle for a ritual African-American meal. It is accompanied by two stools implying shared sustenance.

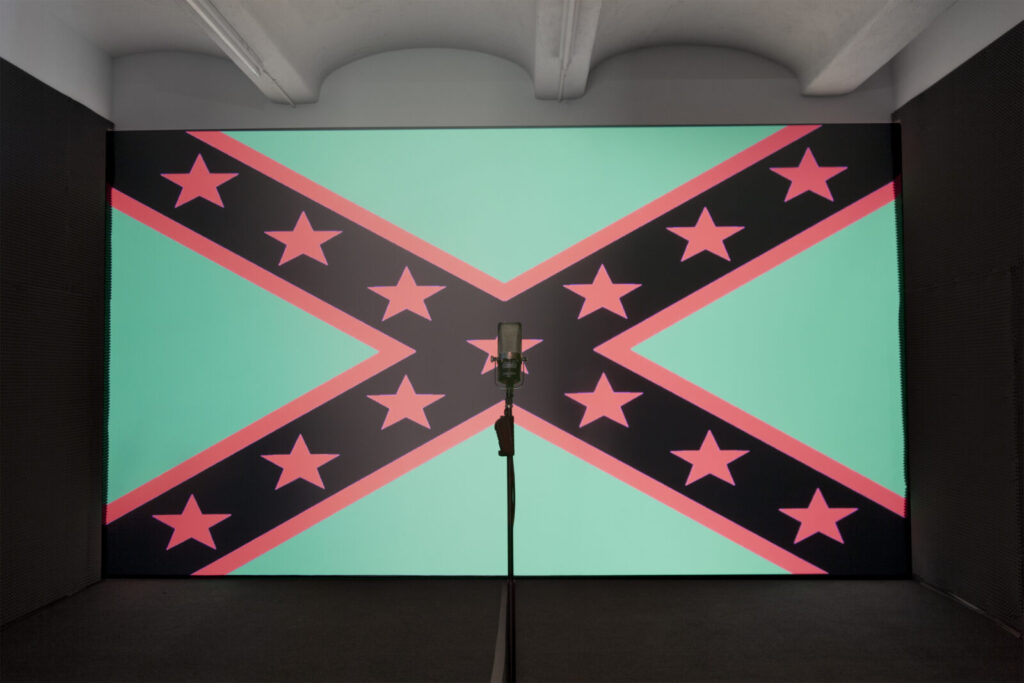

Sonya Clark’s “Unraveling’ is a Confederate flag, the threads of which have been picked asunder to straggling tatters. Part of the magic of Clark’s invention is that we are accustomed to seeing ragged and worn flags in history museums. Clark signals that a new battle has been enjoined and new purposes may be found for the salvaged threads. In his interactive video projection, Hank Willis Thomas recolors the Confederate battle flag into the colors of pan-African liberation, black, red and green. There is a microphone placed before the screen. The video morphs into kaleidoscopic star bursts when the viewer sings along with Thomas’ playlist of R&B classics, thereby enlisting the viewer as part of the implied call to action.

More complicated metaphors provide syntax for a subtly inflected diction of psychological emancipation. “Southern Comfort†by Sam Durant juxtaposes a gray army blanket, an ax handle and a pint of the sickly sweet liquor, Southern Comfort. A symbol of staunch segregationism, ax handles were given away by Georgia Governor Lester Maddox at his fried chicken restaurant. The Confederate gray of the blanket and the Currier and Ives steamboat on the Southern Comfort label collude to cast into doubt the universality of the concepts of southern hospitality and comfort to strangers.

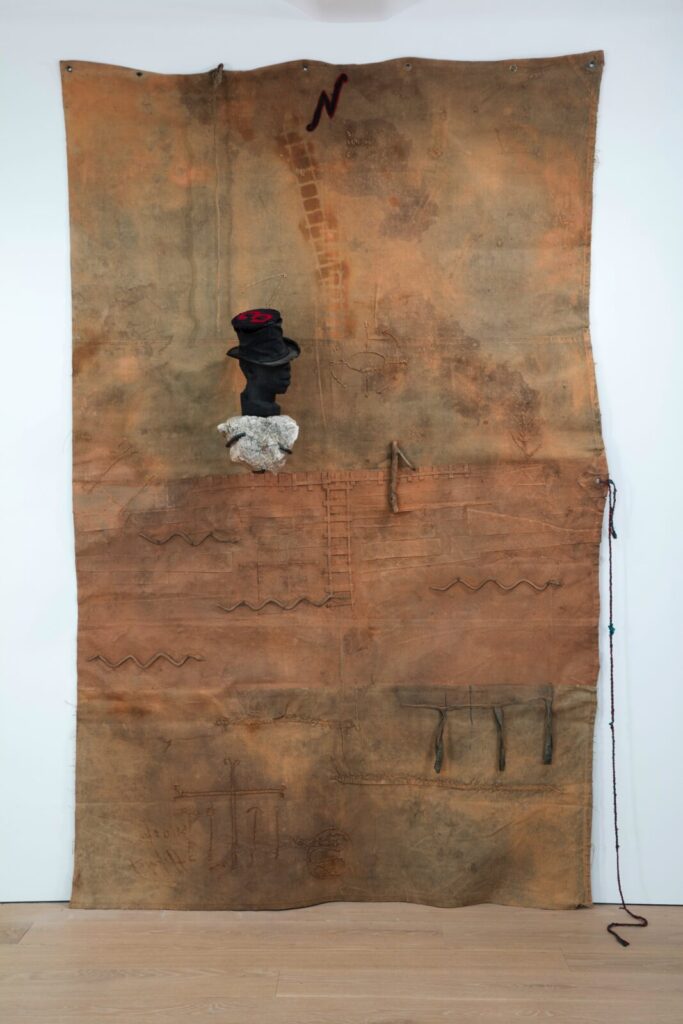

Radcliffe Bailey’s “Up From†is a canvas tarp rubbed with Georgia red clay dirt, Caribbean rum and tobacco, like African sculptures encrusted with sanctifying liquids, but also substances associated with the history of slave labor. An iridescent black head wearing a battered top hat sits on a rock in the upper half, like an intercessor or divine guide for the tracks or ladders stenciled on the tarp. Miranda Lash associates the diverse array of symbols stitched on the tarp with signs from the “Underground Railroad, Yoruba and Kongo cosmology, Haitian Veve  and black Southern artists and craftsmen.†The title may reference Booker T. Washington’s 1901 autobiography “Up From Slavery,†which advocated black advancement through skilled trades. The ladder and snake imagery on the tarp may also reference the ancient board game, Snakes and Ladders,  in which players endure the perils of continual reversals and slipping backwards from the start (bottom square) to the finish (top square) – a potent metaphor for the uncertainties of black American lives in the 20th and 21st centuries.

On May 17, 2017, the statue of Robert E. Lee was removed from its pedestal in New Orleans. On that occasion, Mayor Mitch Landrieu remarked, “I want to try to gently peel from your hands the grip on a false narrative of our history that I think weakens us…Centuries-old wounds are still raw because they never healed right in the first place…We justify our silence by manufacturing noble causes that marinate in historical denial.†Surely his statements go a long way to explaining the reasons for and the power of this show.

In effect, the slate is clean and cleared for a new iconography of the South. Does “Southern Accent” offer a proto-history of that stylistic evolution? Think of Eastern Europe after Glasnost, South Africa in the Mandela Era, or Ireland in the years leading to and after their Civil War with the revival of the Gaelic language, popular song, the Abbey Theater, the paintings of Jack Yeats. If the American South were a foreign country (and it some ways it is), it might be easier to recognize the pivotal character of the present moment.

“Southern Accent: Seeking the American South in Contemporary Art†is foundational, essential viewing for anyone with an interest in regional American art and culture.