Approaching Institute 193 on North Limestone in Lexington, I peer through the storefront window to make my first encounter with Emily Ludwig Shaffer’s paintings. A New York resident with deep roots in Lexington, Kentucky, Ludwig Shaffer treats us to meticulously rendered scenes which engage with visual elements traditionally relegated to second-class citizenship, or else, to the merely “decorative.†A braid adorns a side of a building. A topiary wall pushes forth, and seemingly through, a canvas surface. Plants, in various arrangements, populate the works. As I step into the space, the architecture of the work presents itself. The painted surfaces, at once, acknowledge their illusionistic nature by offering flat color passages and push us into masterfully modeled surreal spaces, wherein the difference between interior and exterior constructions oscillate and meld.

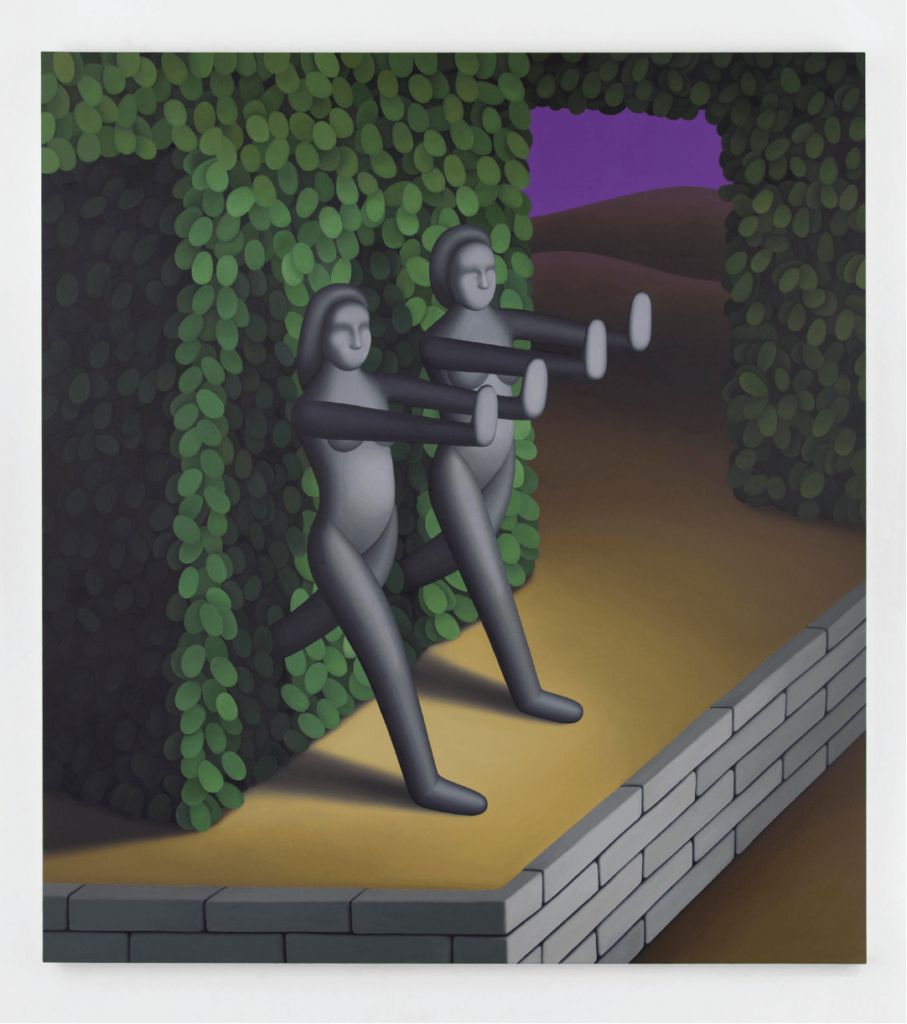

There are no clear protagonists within these subtle dreamscapes, no clue to privilege in any one of their quiet actors. When we are finally presented with the human form, it is that of two monochromatic grey, female sculptures, with arms outstretched in a gesture of refusal—the “No-No dance.†This term, coined by the artist, contributes to the titles of the painting and the show “From the Ha-Ha Wall Comes the No-No Dance†joined with reference to a French garden design feature.

Oil on canvas

72 x 65 inches

Ha-ha is a wall structure that acts as a physical separator without breaking the visual flow of the landscape. Aside from grounding the references to gardens and greenery, which abound in Ludwig Shaffer’s work, this term allows us to speak about “control†as one of the themes explored on the painted surface. Much like the Ha-Ha wall’s ability to assert a boundary while preserving a certain viewing and traversing of the landscape, many of the painted elements govern the viewer’s eye without announcing their presence. This runs the gamut from more literal renderings of walls and hedges within the painted naturescape, to utilizing the physical dimensions of the canvas to interrupt the flow of the composition. Here, meticulously-rendered realism strains against the two-dimensional surface. These compositions effuse a careful balance, presenting elements which both challenge and control one another. This facilitates a productive tension, drawing this viewer back into the painted surfaces in an attempt to discern the visual flows suggested within them.

Another aspect of the works on view that echos control and tension in an intriguing way is Ludwig Shaffer’s treatment of the female body. It is denied specific personhood and, as mentioned earlier, does not function as a protagonist of any narrative suggested in the paintings. It is an object, just like any other within the space of the composition, and in a visual culture that often both centers and objectifies its female subjects, this visual strategy provides an understated yet quite empowering alternative.

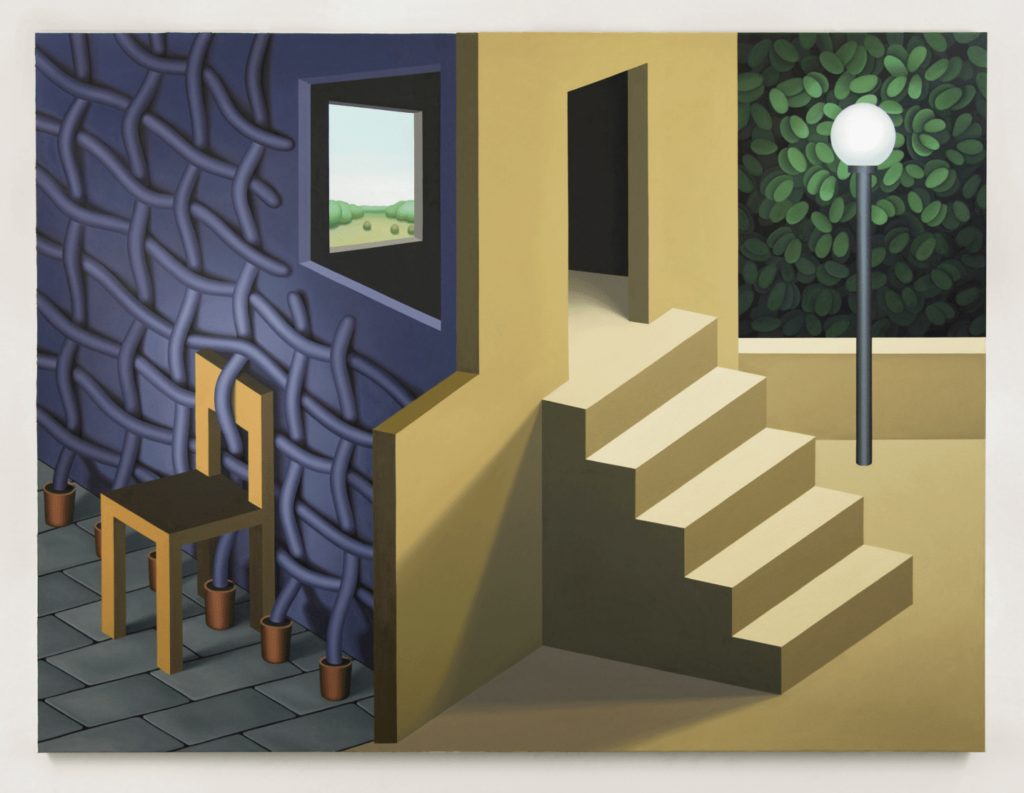

Acrylic on paper

22.5 x 30 inches

When preparing to write about the work, I quickly scanned through a number of historical French garden images. The most famous of these, the Gardens of Versailles, somewhat ironically bill themselves within the two-dimensional space of the webpage as, “The art of perspective.†I find this to be a really interesting point of entry into Ludwig Shaffer’s paintings due to the visual complexity of the interior and exterior spaces that she renders within her work. Although the architectural edges are carefully taped off and delivered to the viewer in a pristine semblance, the actual geometry is compromised: the viewer experiences an amalgam of possible perspective points within a single composition. This signals a very careful and intentional game played by the artist, one full of intriguing visual nuance.

Oil on canvas

72 x 96 inches

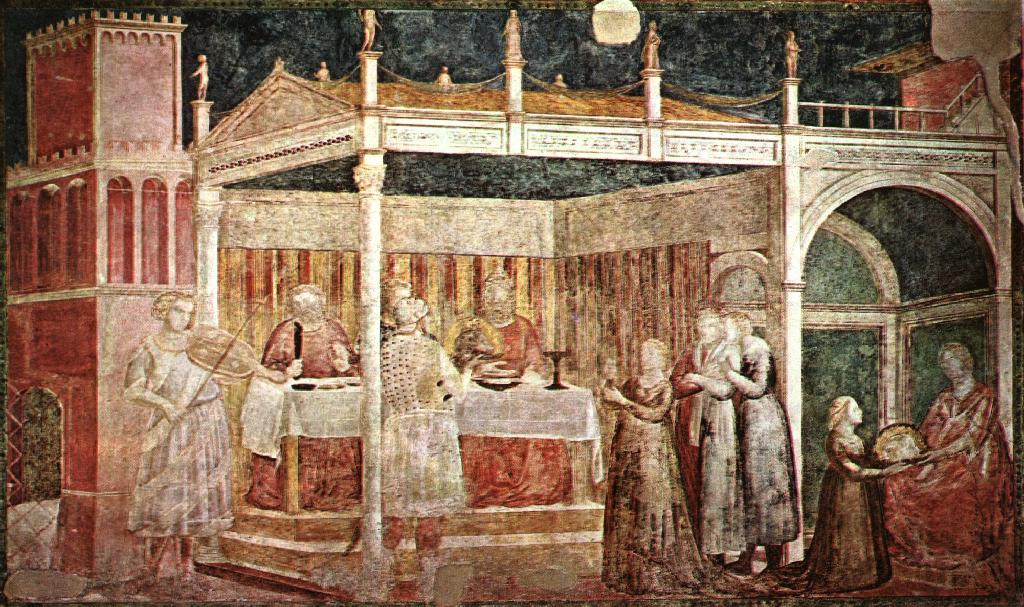

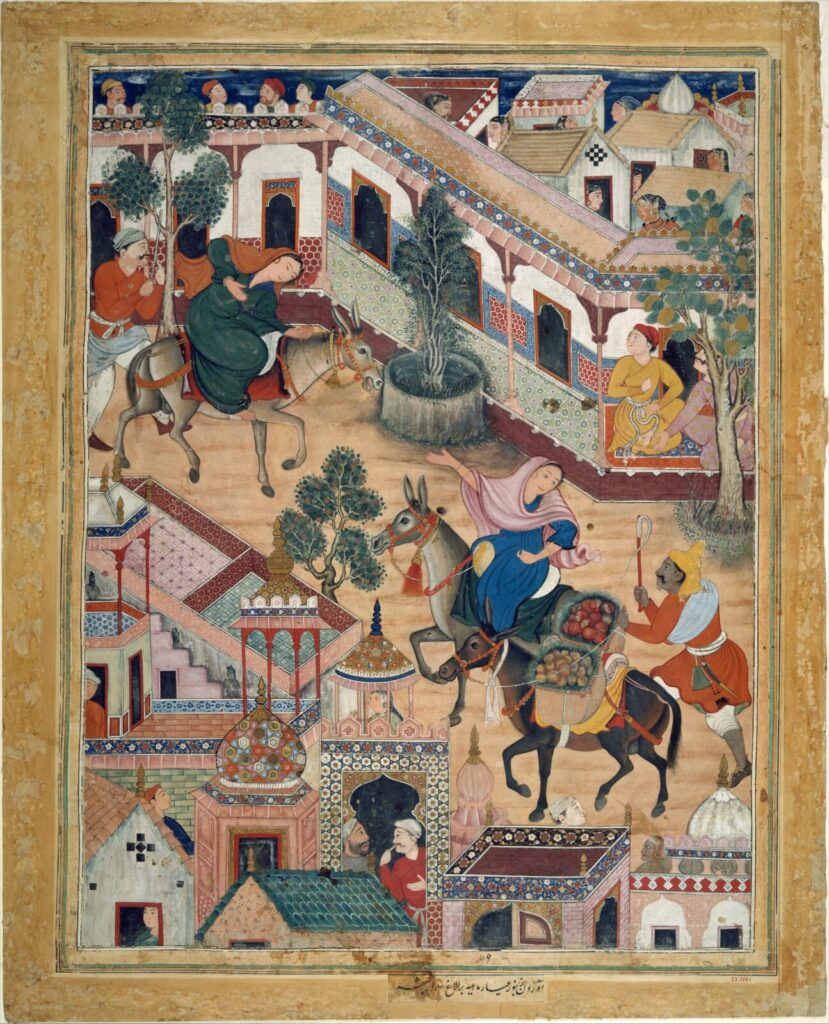

During the exhibition opening, I spoke briefly with Ludwig Shaffer, about possible links to Giotto paintings or perhaps Uccello: visual spaces where the technique of perspective was explored but not equally controlled over the whole of the composition by painters steeped in iconographic traditions. The artist brought up another early source of inspiration, Roman and Greek sarcophagi friezes, where the viewers encounter implied interior spaces which travel between the physicality of carved stone and the illusion of perspective. Upon further communication, Ludwig Shaffer brought up another exciting line of visual influence, Persian miniatures; illustrative works on paper that emerged in the region after the Mongol conquest in the 13th century and subsequent introduction of Chinese scroll painting tradition. Presented within album or book format, the miniatures allow for a completely different way to organize the composition that eschews standard perspective practices of Western painting. These constitute truly intriguing points of departure for the exploration of the painted surfaces, particularly in the art world that is often more concerned with referencing its own mercurial trends, than maintaining deeply-rooted dialogs with the past.

Fresco, 1320

110 x 177 inches

[source: https://www.wikiart.org/en/giotto/feast-of-herod-1320 ]

Attributed to Kesav Das

Ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on cloth; mounted on paper

29 1/8 x 22 1/2 inches

[source: Met collection https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/447743]

It is important to mention, at this point, another aspect of the show, the collaboration with the Michler Family Florists and Lexington-based architect & designer Jason Scroggin, who teaches at the University of Kentucky School of Architecture. Scroggin’s studio designed and built a custom bench seat with planters, which in addition to function, complemented the show by extending the motif of architectural space. This was a feature that many a gallery visitor appreciated during the opening and one that, perhaps, suggested the potential domestic settings the paintings could go on to inhabit in their future lives.

Overall, this is a show that presents us with smart, carefully-balanced, painted constructions. They are not loud. They do not demand our attention. But if attention is given, they are like good books; reminding us how easy it is to lose oneself within tightly crafted layers full of visual games, historical allusions, tactile enjoyment, and nuance.

Emily Ludwig Shaffer: From the Ha-Ha Wall Comes the No-No Dance, runs thru June 8, 2019, at Institute 193 in Lexington.