On February 9th, 2019, I had the privilege of visiting the studio of artist Harry Sanchez, Jr. During our conversations we discussed Sanchez’s creative interests, the art he has been creating during the last five years, and his journey to becoming a full-time artist. Sanchez works out of his home in Northern Kentucky, and the assessments that follow derive from the interactions we shared and the insight Sanchez was able to provide, delving deeper into nuances of his work that may go unnoticed in his exhibitions or on his website.

Geographical borders seem to dominate headlines, chyrons, and posts nowadays. In America, immigration, electoral redistricting, and boundaries between metropolitan centers and rural communities contribute to the discourse around borders.

Internationally, too, trade agreements are being re-shifted and unions are breaking. As a result, the attention dedicated to the concept of borders is driving individuals and groups to consider how they feel about others who may not necessarily share their perspectives, skin color, or life experiences. Amplified by ratings-hungry television networks and social media, widespread rhetoric about those directly impacted by border debates are arguably at their most contested, violent, and perhaps uninformed, since the end of World War II.

Harry Sanchez, Jr. strives to critically unpack the images and messages surrounding borders, specifically as they pertain to immigration in the United States. Moreover, Sanchez utilizes a vast array of media to render the impressions of the people, policies, and activist groups tied to immigration in America, subverting familiar narratives and iconography in the process.

Yet his work considers the multiplicity of borders as a term: the sculptures, paintings, and prints he creates make plain the consequences of social regulations and rules, celebrate—for better or worse—difference and sameness, and test the potential of his materials and art’s polarizing nature in general. While Sanchez claims that “the one overarching thing my work is about is abusive power,” the most apparent catalyst for his practice is how borders affect daily life in 2019.

Sanchez is no stranger to borders, at least in the physical sense. During his lifetime, he has lived on the borders of New Jersey and Pennsylvania, Connecticut and New York, and Kentucky and Ohio, where he currently resides working as a professor at the University of Cincinnati. The border that resonates most with him as an artist, however, is the one where he was born—in El Paso, Texas, on the border of the United States and Mexico.

Sanchez maintains a dual-identity as a Mexican-American, and his work rebukes the policies and attitudes regarding immigration and people with brown-skin (like Sanchez) being advocated for by the current White House Administration and its support base. Having first-hand experience of life on the Southern border—and having lived in varied locations throughout the country—Sanchez understands the realities facing the groups being oppressed based upon their country of origin and skin color, as well as the myths about them being perpetuated by certain groups.

The themes of Sanchez’s work are complex and historical. It may be no surprise, then, that Sanchez adopts a range of media and materials, some of which are unconventional, to address the full impact of borders. He also channels his own history. His journey to becoming an artist stemmed from a prior occupation as a cake decorator, so he finds ways to incorporate the skills and tools associated with baking into his art. Notably, he applies paint using decorating bags, squeezing dollops, stripes, and flowers onto his surfaces. When reflecting on how his practice encompasses the notion of borders, he states, “It’s partly a reference to the paint—breaking the rules of painting…How can we make painting sculptural?” With baking equipment, Sanchez pushes the limit of the paint, nearing the boundary of what it is capable of doing.

Elsewhere, as in Thoughts and Prayers (2016), he arranges .223-type bullets in text of the sculpture’s title on a wall or panel. This work juxtaposes the agency of gun violence with the seemingly distant and automated responses from politicians and civil leaders when acts of violence occur. Using these techniques are advantageous, insists Sanchez. “If I did my Thoughts and Prayers with paint dollops, it’s not the same as using live. 223 bullets, when these are the same bullets that are causing so much death and destruction on a daily basis in America.” Whether using non-traditional materials or not, the artist demonstrates a careful selection of medium, which often assists in generating the intended experience for his audience.

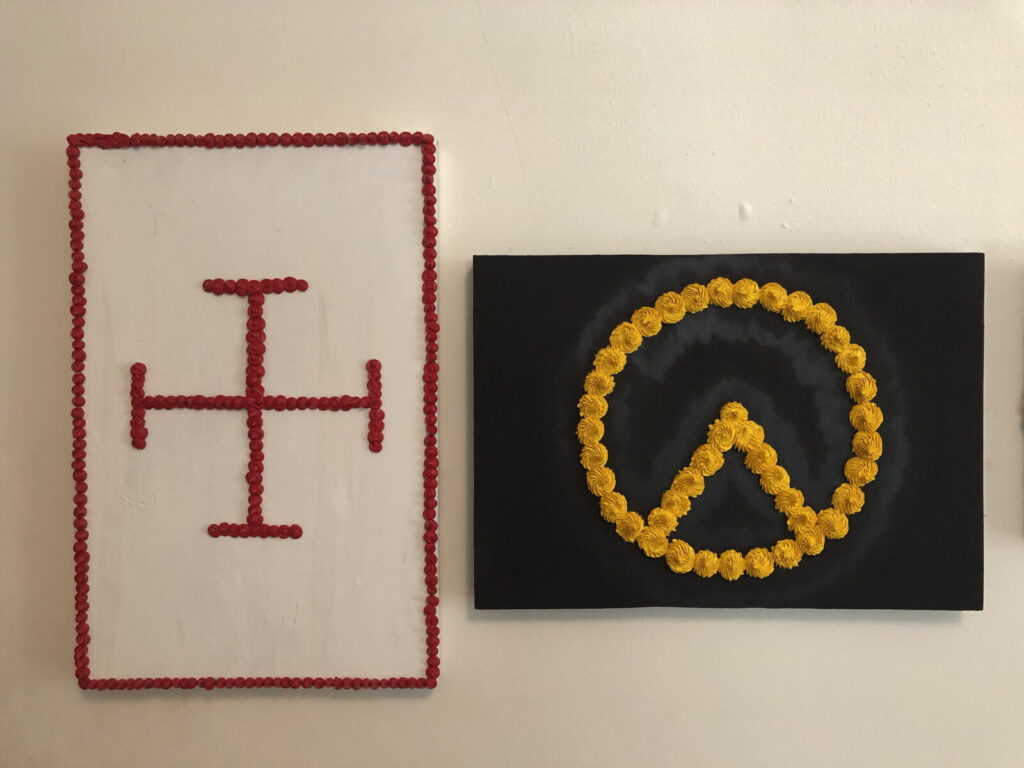

For instance, Sheet Cakes (2018-present), which visually resemble the kinds of objects Sanchez tended to as a cake decorator, are also indicative of flags, containing a variety of crests, stripes, and emblems. A single white rose rests where two black diagonal stripes overlap in I Am The LEAST Racist Person You Have Ever Met; a black border envelops the rectangular contour of an otherwise white panel. In another titled We Thought He Was Going to Protect Our Jobs, and then BOOM!, a yellow four-pronged pitchfork appears in a circle with studs protruding all around. Like the other cake painting, this work features a decorative border around a solid background. In most of the Sheet Cakes, there are moments when the paint reads as having been applied hastily, a purposeful technical feature paralleled by exposed hardware in the painting’ support frames.

The flags that Sanchez refers to are those hoisted by alt-right protest groups. Among them, he depicts the Confederate flag and the banner of the Traditionalist Worker Party—two flags flown by American groups—as well as the flag of the European-based group Génération Identitaire in Just a Fraternity or Social Club, where dollops of yellow paint form a circle against an expanse of black; a peak juts from the bottom arc of the circle. Normally, these flags and signs can be found at protest events across the world, especially events focused on immigration and border politics. They may also make themselves known to the general public as background imagery during televised rallies or in photojournalism. The intended quality of Sanchez’s craftsmanship accentuates the use of these symbols on picket posts, wherein a sign’s dexterity is often less important than content and visibility.

When asked what it means to create these images, Sanchez replies, “I’m not saying ‘this is what I stand for.’ I’m presenting these with a historical message. Cake decorating has a history of white supremacy and slavery.” He posits that by using decorating tools to produce these flags as cakes (as masses of condensed sugar), his work retains a connection to the history of the sugar industry. Particularly, his paintings recall slavery during colonial America, when slaves labored for long hours harvesting sugar and preparing food for their owners. “I’m just taking [the alt-right group’s] signs and making it what they should be made out of.” By this, Sanchez alludes to the white supremacy advocated by these groups, the palpable legacy of institutionalized racism, and the celebratory capacity of cakes—his Sheet Cakes embody the ideals of racial purity lauded by many alt-right protesters.

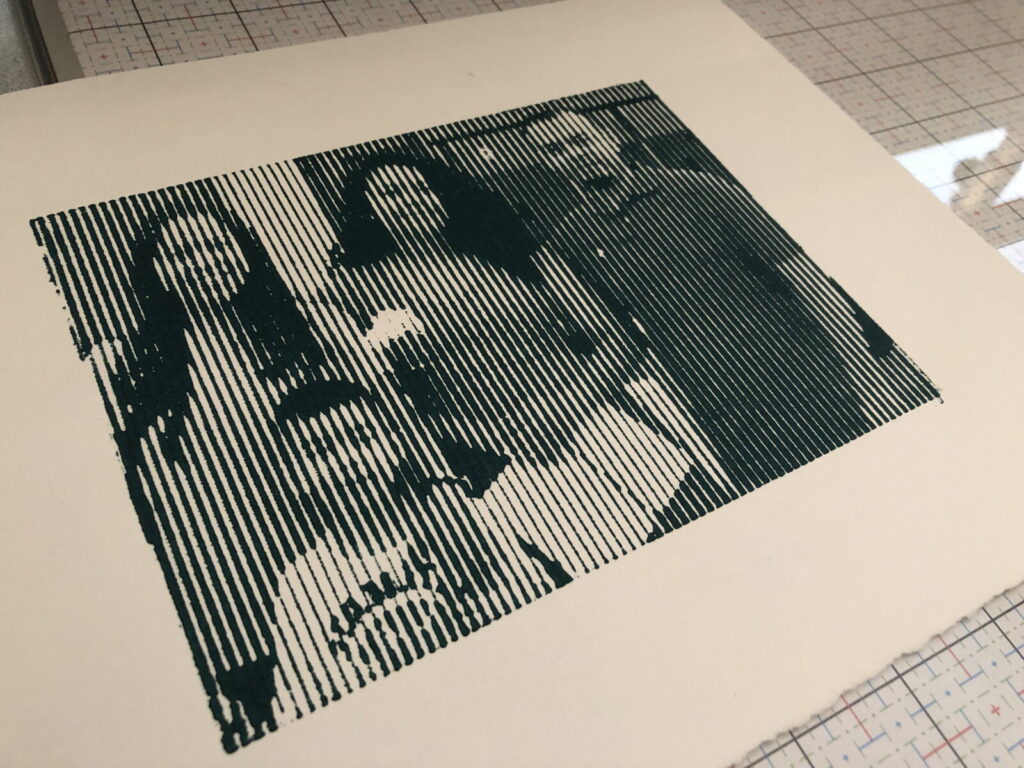

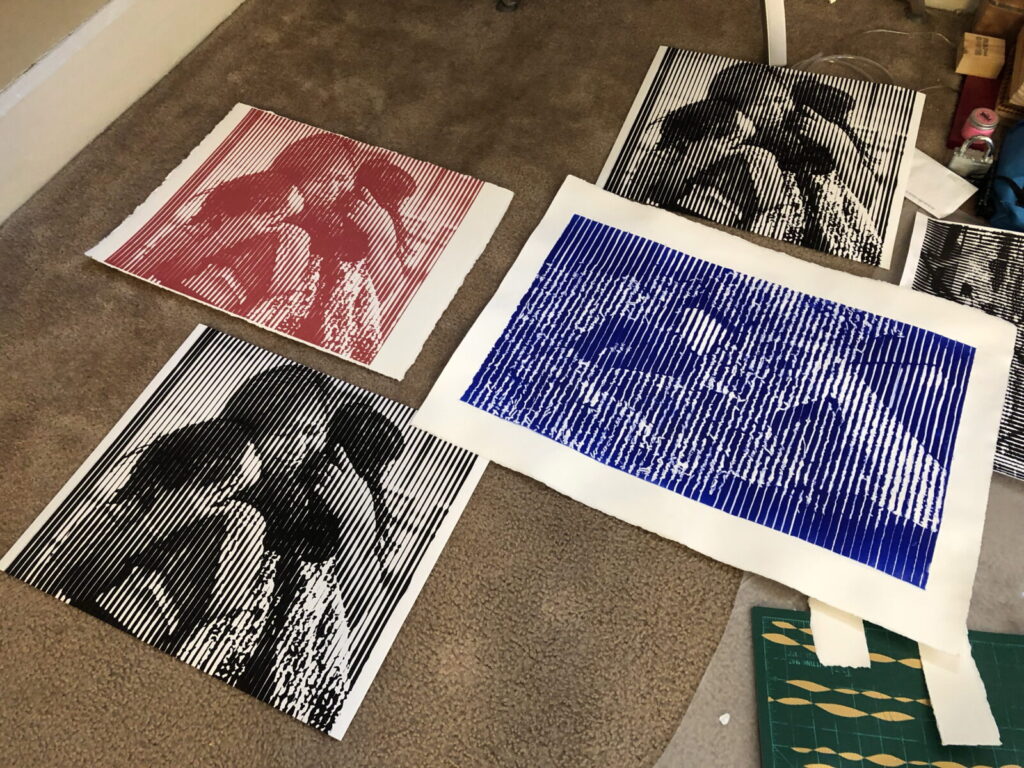

Though the subject matter in Sheet Cakes is arguably inconspicuous, the series is inherently combative towards the people and groups it is about. Sanchez is unabashed in labeling alt-right groups as white supremacists; his mode of delivery—flags as cakes—is both cynical and somewhat irreverent. On the other hand, Sanchez is remarkably empathetic to individuals afflicted by border policies aligned with the ideologies of the alt-right. With Torn Apart (2017-present), a series of prints documenting deportation as political practice, Sanchez is able to express these sentiments. Here, he collects reference images of deported immigrants who have no criminal background and reproduces them in halftone, where the color of the ink is constant but the width and spacing of it vary. The end result mimics the effects of newspaper photographs. With titles carrying the names of the individuals he portrays, the prints of Torn Apart are perhaps the most effective of his artworks at achieving his documentary aspirations.

Exactly who Alejandra Juarez is in one particular print is unclear. Three young girls appear to be comforted by an older woman—perhaps their mother—while two men in suits oversee the situation. The print reads as the final moment before at least one of the women is deported, the last opportunity for a good-bye. Sanchez’s heritage, presumably shared with the figures he introduces, is conveyed through the green, white, and red palette—the colors of the Mexican flag. But it is his method of printmaking that he believes denotes his ancestry strongest. On what viewers may not be aware of with this body of work, Sanchez asserts, “You might not know that I’m referencing my heritage as a Mexican-American. You know, the halftone,” an insinuation to his dual-identity. In other prints, such as Maribel, the green and red ink overlap, creating a hue near to black—a formal marker for the dire circumstances these people enter into, at times without warning.

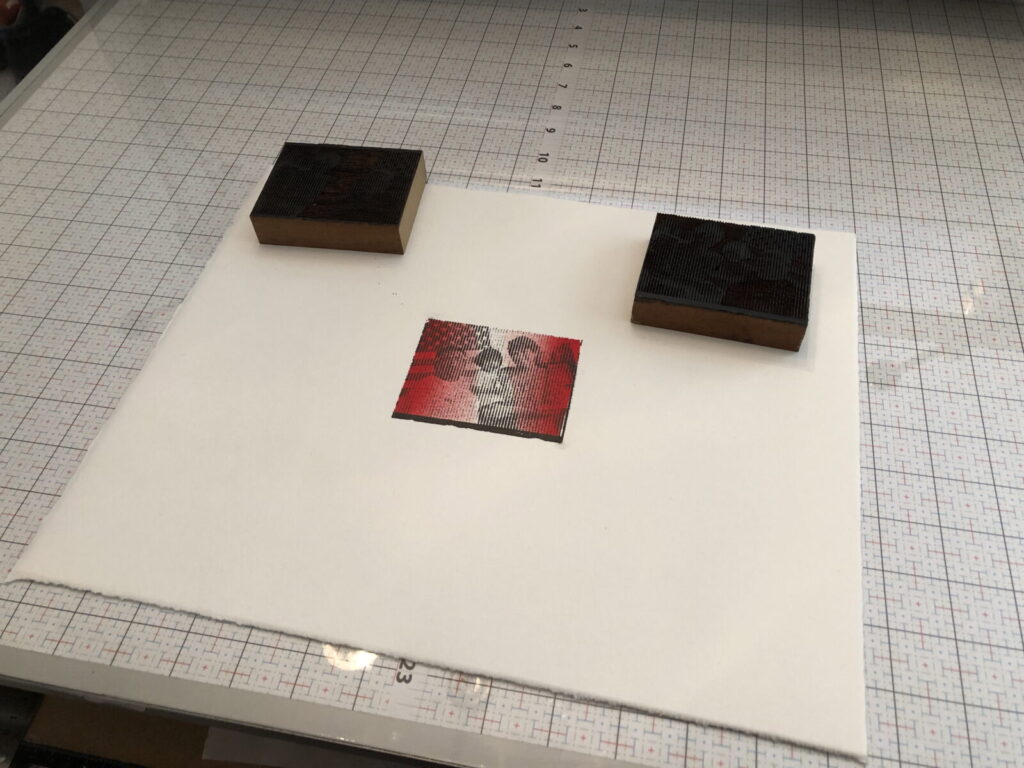

Sanchez achieves the halftone technique by inking a sheet of acrylic plexiglass, then uses Q-tips to meticulously remove sections of ink. He does his best to stay true to his reference images, which have been altered on his computer, then printed from inkjet printers to match the final halftone objective. The halftone is illustrative of what is happening to his subjects, emphasized by the reductive qualities of his process. “It’s the actual erasing that’s causing these images to be made,” Sanchez says, referring to both his erasing of the ink as well as the regulated erasing of immigrants from the United States. The halftone, in a kind of double meaning, is also a surrogate for the border wall in El Paso Sanchez was used to seeing in his youth, which he recalls as being made of vertical slats placed side-by-side, stretching for hundreds of feet. His technique is at once his and his subjects’ shared identity, a reminder of their vulnerability, as well as the tangible object that stands as a testament to racial and ethnic oppression in America.

When Sanchez creates his Torn Apart series, he uses a printing press installed in a room connecting his living room and kitchen that he has converted into a studio. When producing an individual print, Sanchez places a traditional Mexican blanket under the press’s roller to protect and apply pressure during the transfer of ink from plate to paper. Lately, Sanchez’s printing practice has expanded to include plates made from small, laser-cut wood blocks. What’s more, in addition to traditional printing ink, he has begun making prints using resin powder. For Sanchez, his practice navigates the border between traditional and novel modes of printmaking, spurring discovery for himself and his materials.

Sanchez describes his process “like a dance. I try to think it’s like a symbiotic relationship.” By this, he speaks to what he is able to accomplish given the limitations of the media, equipment, and tools he uses. For example, Q-tips that pick up ink from acrylic plexiglass can only be so precise when describing the contours of a face, and so Sanchez must plan for and accept any formal imperfections that arise. Such is the case, too, when handling cake-decorating equipment, which Sanchez admits can be trying on both him and the paint. “I’m asking the paint to do something unnatural. It’s a forceful thing, creating this pressure squeezing the paint out of the bag. I’m putting a lot of pressure on this, [to] hold form, and stand up.” In his studio, any number of materials and equipment are at the ready, allowing him to flow freely between his multiple bodies of work that contain similar conceptual themes.

Indeed, there are certain characteristics shared between Sheet Cakes and Torn Apart. For one, they each address an extreme of present-day border politics in the United States—Torn Apart with those being deported and oppressed, and Sheet Cakes with the groups who publicly demand the removal of specific cultures. Formally, they are both born from work Sanchez created during his time as a graduate student at the University of Cincinnati.

His MFA Thesis exhibition presented selections from All for Naught? A Whistleblower Series (2016), a group of portraits of figures who in recent years have exposed abuses of power, like Edward Snowden, who leaked NSA documents regarding global surveillance; Julian Assange of Wikileaks notoriety; and Samira Saleh al-Nuaimi, an Iraqi human rights lawyer captured, tortured, and murdered by ISIS in 2014. Sanchez renders the faces of these icons in halftone generated by paint dollops made with decorating bags. The halftone in All for Naught, in contrast to his newest work, does not necessarily allude to the heritage of Snowden, Assange, and others. Rather, the dual-identity pertains to the actions these individuals take to unmask corruption at the highest levels, which can draw considerable amounts of praise and discontent from different groups across the globe. They are either civil heroes or criminals, depending on you may ask.

Prompted with any risks he may be taking, Sanchez is quick in response. “One of the biggest risks is being an artist,” he claims, “Being an artist is not easy.” Drawing comparisons to his time as a college football player, Sanchez says, “Playing football and getting my ass whooped on the field helped a lot. When you physically get beat down, and you have to physically get back up…I totally understand having to get up and be thick-skinned.” As a graduate student, Sanchez endured public scrutiny with an installation called The Lynching of November 8, 2016 (2016) at a campus gallery. The artwork comprises an American flag balled up and hung from a noose attached to the gallery’s ceiling. A rather simple presentation, Sanchez nonetheless received an ample amount of criticism and local press for the gesture. His reactions to such attention are prelude to the kind of empathetic yet staunch nature fueling his later work.

Interviewed by one media outlet about the installation, Sanchez contends, “One group is so hateful to another group and there’s such a lack of understanding[.] It seems like if we don’t get past this we’re going to crumble as a nation.” The flag installation does not concern the kind of border politics his other works address, nor does it explicitly emphasize the specific (art) historical connotations of the American flag or nooses. Instead, The Lynching of November 8, 2016 explores the boundaries of public consumption—what is most likely to garner feedback?—as well as the kind of imagery that stimulates adverse behavior and marks the threshold that instigates feelings of vulnerability when crossed.

The trajectory to becoming an artist for Harry Sanchez Jr. was, to some degree, unplanned. His story includes time as a construction worker, cinema usher, and cake decorator, the latter igniting his desire to create in such a way that the trade’s techniques are now his preferred methods. His nomadic life along with his upbringing in El Paso are his primary conceptual departure points, yet his practice stretches across a multitude of topics and materials. While divergences between his paintings, prints, and installations are readily apparent, they align in the ways in which they address pressing issues of the zeitgeist, especially with concern to the notions of borders, limitations, and rules. Borders for Sanchez are both subject matter and vehicle for expression. His art underscores competing lived experiences, bringing to the fore the various borders we surround ourselves with, whether consciously or not, to reinforce predetermined ideologies. Sanchez urges his viewers to unlearn their biases and embrace recognizable differences.