Food is central to our daily lives. It provides necessary nourishment and pleasure, as well as aggravation and anxiety. What and how we eat informs our identities in terms of gender, class, and ethnicity. Eating shapes our social relations with others and our environment. However, these are not abstract associations, but intimate and specific experiences that encode desire, taste, tradition, ritual, and etiquette. Much of Lori Larusso’s work explores the unwritten rules and underlying effects of the domestic activity of making and consuming food. With meticulously applied layers of bright glossy paint, she lovingly renders delicious confections and delectable meals, as well as kitchen and dining room disasters, to make us consider how food communicates effective experiences, psychological states, and moral dilemmas.

In her painting If you can Bake a Cake, you can Make a Bomb (2017), a dozen splattered eggs appear on the floor of a pristine powder-blue kitchen. As the title suggests, cakemaking has turned incendiary. Perhaps the baker, frustrated by the expectation of bourgeois domestic perfection, has turned against her craft. Or alternatively, maybe the chickens themselves have revolted against the pilfering of their eggs for use in our cakes, as intimated by dark silhouettes of barnyard fowl that appear in the cabinet-turned-chicken-coup under the kitchen counter. Either way, the broken eggs convey that something is amiss in this seemingly idyllic yet creepily sanitized American home.

In fact, a feeling of unease haunts all of Larusso’s immaculate surfaces. In Trickle Down (2013), a double chocolate chunk ice cream cone oozes sticky sweet cream onto the floor of an otherwise picture perfect interior. A cozy fire burns in the fireplace, as sophisticated busts and vases of flowers rest on an adjacent bookshelf. This mid-century modern home could be in Dwell magazine if it were not for the fallen ice cream cone that ruins the image of upper middle-class luxury. There is a tension between the cheap treat in the foreground and the impeccable home behind it, as if to suggest that we must be satiated with small affordable pleasures while an unattainable dream lies just out of reach.

The atmosphere of this picture is one of frustrated desire. In an economy where wealth and opportunity are supposed to “trickle down†from rich to poor, yet rarely do, we are torn between settling for brief moments of feeling good and aspiring for something better through real political change. Embodying this tension, Larusso’s paintings recall what literary theorist Lauren Berlant describes as the “cruel optimism†of the American Dream, or a condition in which “something you desire is actually the obstacle to your own flourishing.†Much like the sentimental fiction that Berlant describes in her writing, Larusso’s paintings capture the combination of fantasy and futility that characterize the mirage of accessible abundance propagated in the US. Although we are accustomed to wanting things that we know are probably bad for us, like that double chocolate chunk ice cream cone, the stakes are higher when we desire a better lot in life. And these paintings register this intense longing to believe in meritocracy and upward mobility, as well as the sense of resignation and exhaustion indicative of the new economy that thwarts that promise. Â

Larusso’s works appear as stages for dispirited characters who are perhaps in the process of relinquishing their fantasies. Whether visualizing the specter of economic precarity or environmental degradation, her paintings evoke conflicted responses to everyday experiences that we sense affectively even if we don’t register them cognitively. Lunch By The Dumpster (2013) brings to mind a quick break to eat a packed lunch by the dumpster before returning to one’s minimum wage-paying job, as well as the post-consumer waste that haunts even the smallest of meals. I’m Sorry (We Are Garbage) (2017), which depicts an apologetic party balloon attempting to lift a plump white trash bag out of a metal bin, recalls the profuse amounts of trash produced by the average American party. Although we’d probably rather forget all the decorations, paper plates, plastic utensils, gift wrappings, and food remains that get stuffed into bags after the event is over, this painting reminds us that this is part of who we are. Our garbage does not just float away after we toss it in the bin, even if the weekly trash pick-up makes it seem so.

Like Berlant, Larusso is concerned with ordinary moments and encounters more than major events and big revelatory gestures. For this reason, as well as her humorous, colorful, and representational style, Larusso’s paintings were received earlier in her career as lacking “seriousness.†This perception recalls the criticisms leveled at Pop artists during the 1960s. However, Pop was redeemed by its “coolness†that conveys a sense of neutrality, detachment, and impassiveness when approaching themes of consumerism and the everyday. These masculinist imperatives, as feminist art historians Cécile Whiting and Kalliopi Minioudaki have respectively shown in their writings, were also mobilized to exclude female Pop artists who were deemed too personally invested in their subjects to be properly Pop.

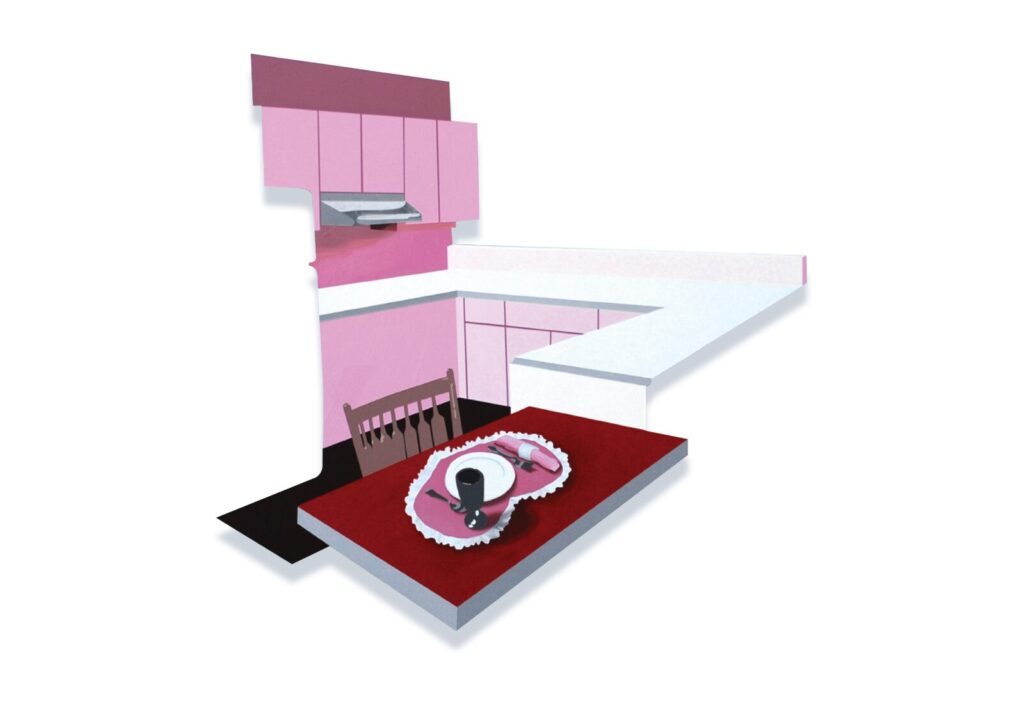

Similar to her feminist Pop precursors, the convivial yet disturbing domestic scenes of Larusso’s “Shapes†series (2007 – 2014) feel engaged and impassioned more than cynical and impersonal. Pithy suggestive titles like Boil, Fried, Cracked, Wrecked, and Hungry are common in the series and reinforce the impression that all is not well in these seemingly happy homes. Although no people appear, Larusso strategically uses absent objects or out of place elements to make tangible the feelings of hunger, exhaustion, abuse, self-loathing, and unrequited love of the characters that one imagines inhabiting these spaces. In Hungry Heart (2010) and You Used to Blog About Cupcakes (2013) from the series, the oven—which is absent in the former, and defunct in the latter—serves to heighten the melodrama of the scene. Almost anthropomorphized, its open door seems to cry out, exposing the void within. Similarly, eye-catching colors like Pepto-Bismal pink, bright white, and chocolaty brown intensify the mood of anxiety, longing, and disillusionment of the once recognized food blogger who has recently abandoned her craft. In this way, Larusso orchestrates these compositions to capture a frustrated belief in the good life, speaking to what Berlant describes as the “dramas of adjustment†that characterize our age of growing income inequality.

Berlant builds on what Raymond Williams calls the “structure of feeling†or the intuited contours of a particular space in time that gives one a sense of the possibility of certain futures over others. Through her shaped paintings, Larusso brings into relief the pain, stress, and humiliation of hungry hearts that cannot be sated. However, this yearning is not only met with refusal and despair, but also compassion and optimism. Through humorous juxtapositions and exquisitely detailed subjects, Larusso conveys a sense of attachment to the world she depicts. And by accentuating its contradictions, her paintings offer a space to recalibrate and resist the patterns of life that we have come to expect. As Larusso states: “I am, in part, searching for the tipping point. When does one decide to alter their systems of belief, behavior, and take action? Is a revolution necessary, or can we incite positive change in our lives by individual acts of resistance? What does resistance look like?â€

In her recent “Non-compliance†series, works like If you can Mop a Floor, you can Exercise Total Personal Non-Cooperation (2017) and If you can Perform a Striptease for your Husband, You can Perform a Lysistratic Non-Action (2018) set the stage for such individual acts of resistance. Cast-off objects like the mop and bra imply that someone has reached their breaking point and abandoned their chores mid-action. And because there are no people in these works, animals often activate the scene. Whether they be dead cockroaches swimming in a pool of mop water or an orange pussy cat turned doormat-sized area rug, these creatures produce a tension between a repugnant foreground and alluring background.

This pull between attraction and repulsion also animates Larusso’s “Eating Animals†series (2017 – ongoing). Works like Strawberry Short Snake, Broccoli Poodle, and Radish Mice morph fruits and vegetables into cartoon animals. Inspired by blogs posts and Instagram images taken by parents who aspired to shape these foods into more appealing forms for their children, Larusso explores this strange phenomenon in which edible items are transformed into animals that are socially unacceptable to eat in order to somehow make them more appetizing. This convoluted game while initially appearing absurd, invites one to think about the bizarre nature of the highly processed and packaged foods that the average American regularly consumes like chicken fingers and pumpkin spice lattes.

Although staged and idealized in advertising and social media, food entails messy and entangled systems of procurement, preparation, and consumption. Drawn like the rest of us to the flawless and filtered images of mouthwatering delights that appear in glossy magazine pages and populate one’s social media feed, Larusso takes this source material and transforms it into complex pictures that register a sense of precarity lurking beneath their appetizing surfaces. In her series “It’s Not My Birthday, That’s Not my Cake,†different kinds of cake communicate a range of emotional states. Each one with its candles extinguished has been wished over and awaits devouring. Coconut Cake (2010) appears stout and proud despite the shaky green lettering that timidly spells out “Happy Birthday.†In On A Doily (2014), thick layers of rust colored icing cover dense chocolate cake which sits atop a delicate bed of white lace that seems to float effortlessly under the weight of the cake’s burden. Across the series, the cheerful colors of Larusso’s celebratory confections invite one to contemplate the complicated range of emotions generated by those delicious things that are in fact not yours to enjoy.

This complicated space of longing is eloquently captured in the poems written by Carrie Green to accompany Larusso’s painting in their co-authored chapbook. Dedicated to “women artists everywhere, whether their medium is words, paint, or buttercream frosting,†the book is an ode to the overlooked domestic labor of cake baking and decorating. In its last poem, “Not Your Cake†Green’s ekphrastic text brings to life the space of desire embodied in Larusso’s painting It’s Not My Birthday, That’s Not my (Strawberry Short) Cake (2010). It reads:

The cake winks from behind

the neighbor’s starched white curtains

strawberries and cream and yellow cake

striping a green Formica background

You spent your last birthday

eating boxed macaroni from the pan.

Now you imagine the layered sweetness:

moist cake, rich fullness of cream,

tart bite of farm-stand fruit

carried home in the green paper cartons.

The kitchen is empty, washed pale

with early June light. Did you miss

the singing, the bright bouquet

of balloons marking the mailbox?

Flame has blackened the candlewicks,

and someone has served a generous slice

or two. The missing wedge

opens to you, an invitation.

It’s not your birthday. But why

couldn’t this cake be yours?

Although quieter in their sentiments, the paintings reproduced in It’s Not My Birthday, That’s Not my Cake highlight Larusso’s long-standing interest in how the seeds of change are sown into ordinary experiences. Seeking to re-contextualize revolution on a micro-scale that speaks to the complex entanglements of the domestic sphere, her paintings ask questions about how our intimate experiences with food educate and enculturate us, serving as a vehicle to alter the world in which we live.

UnderMain would like to thank The Great Meadows Foundation for support of our 2019 programming, which will include twelve in-depth studio visits of Kentucky artists. See our other publications related to this project:Â

Emily Elizabeth Goodman visits Melissa Vandenberg

Hunter Kissel visits Harry Sanchez, Jr.Â

Jim Fields visits Skylar Smith

Keith Banner visits Michael Goodlett

The Great Meadows Foundation is a grant giving foundation whose mission is to critically strengthen and support visual art in Kentucky by empowering our community’s artists and other visual arts professionals to research, connect, and participate more actively in the broader contemporary art world.