To commit to writing about Ebony G. Patterson’s exhibition at the Speed Museum requires acknowledging my professional relationship and friendship with the artist, and these facts:

1. I met Ebony at the University of Kentucky in the summer of 2014, and asked her if anyone had contextualized her among the artists of the 1970s Pattern and Decoration movement, including Cynthia Carlson, Joyce Kozloff, Robert Kushner, Miriam Schapiro, and others. She said no. Since then, several curators have linked her work to this historical period, while clarifying that her opulent constructions using beads, glitter, and brooches refer to her native Jamaica and festivals like Mardi Gras and Carnival, rather than the mining of supply stores on Canal Street in Manhattan.

2. A year later, curator Janie Welker and I included Patterson in Bottoms Up: A Sculpture Survey show at the UK Art Museum, locating her installation of five elevated coffins covered in fabric and tassels from her performance, Invisible Presence: Bling Memories, near a John Ahearn portrait bust and a Felix Gonzalez-Torres stack of posters showing a bird in flight and gray clouds, among other 20th and 21st century works.

3. I contributed an essay* to the online publication that accompanied her fourth solo show at Monique Meloche Gallery in 2019, titled …for those who bear/bare witness…. Patterson’s installation strategy for that exhibition carries over to the survey that originated at the Pérez Art Museum in Miami, her largest to date, and made even bigger with the addition of several works at the Speed Museum, where it is on view until January 5, 2020. My thoughts on that exhibition follow.

…while the dew is still on the roses… starts at the museum’s title wall with a deep purple background color and shimmering vinyl, clusters of silk leaves, flowers, and vines emerging from the walls and ceiling. This effectively telegraphs what will follow, as we are led down a path into a “night garden†that frames works featuring defiant and dismembered bodies of men and women that the artist has used as protagonists for the past several years.

We begin with a gallery filled with the projection of a three-channel video from 2012, titled The Observation: The Bush Cockerel Project, A Fictitious Historical Narrative. Two male figures are covered in floral patterned clothing that situates and masks them in a dense tropical garden. Their faces are covered by elaborate plumage, and they pose and preen while passing the small body of a baby between them. “Bush cockerels†are wild roosters, and these two – one black and one white – are silent and purposeful. They blend into their surroundings and their actions are not easily decoded.

In the following sequence of galleries we are treated to numerous works installed against fabric wallpaper showing details of a garden at night: a gridded pattern of moist dormant flowers in a palette of purples, gray, and white. Like other artists who have designed wallpaper to serve as backdrop for singular works (think Andy Warhol’s cows and Maos, and Robert Gober’s torsos and genitals), there is the risk of erring too much on the side of mise-en-scène and sacrificing the viewing of individual paintings and sculptures. Add to Patterson’s use of this wallpaper, her staging of abundant artificial flowers that cascade in and around her photographs, tapestries, drawings, and sculptures throughout the exhibition. I could not help but wonder, “How much is too much?â€

Dead Tree in a Forest… from 2013, is a large mixed media work featuring checkerboard and leopard-patterned figures and a visible rooster, situated in a shifting green floral field. Its thick black frame fares well against the wallpaper, protecting the lively action at the paper’s edges from being absorbed into the larger wall treatment.

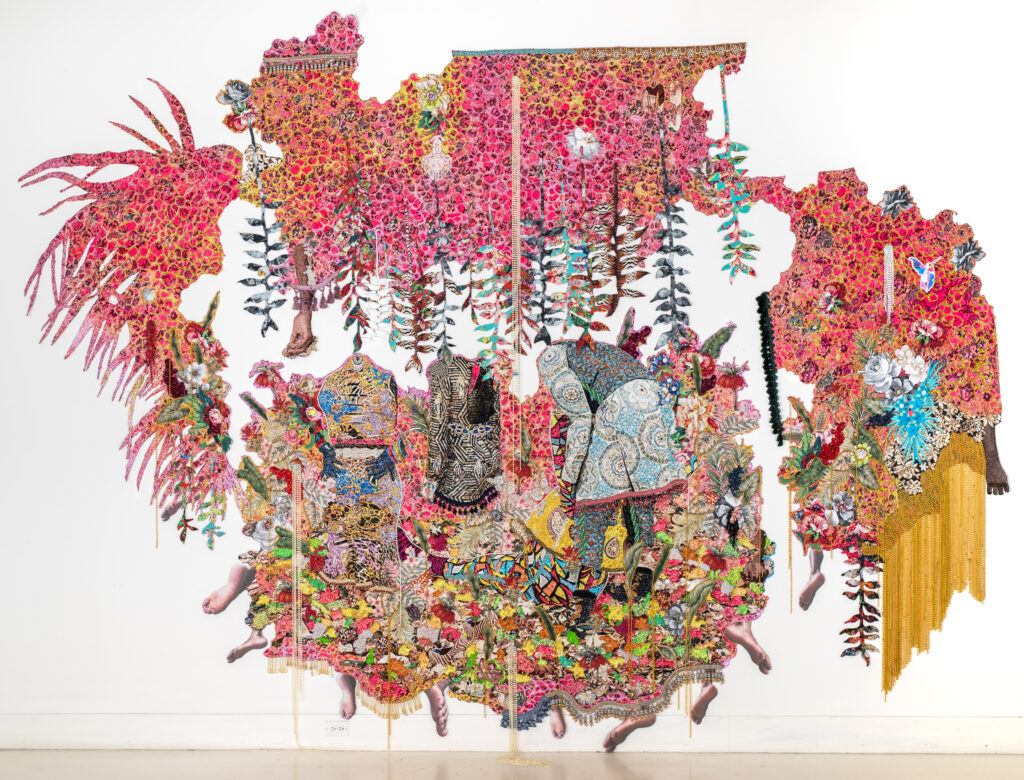

I’m convinced that other 2018 works from the …for those who bear/bare witness… series are compromised by the ubiquitous background and fake flowers. These carefully assembled tapestries, with their precise cuts and layering of printed, cast, and found elements, are hard enough to sort out when presented against a white ground. The anonymous victims memorialized by these works demand to be seen, and that seeing takes time and focus. The artist insists that we don’t look away, and yet her desire to make a unified environment made me do just that.

Patterson’s strength is orchestrating a complex realness and fakeness in dense pictorial fields within specific works. Bodies abound, undone by acts of dismemberment and overwhelming adornment. Headless matriarchs search for missing children, their own bodies festooned with strands of ribbon and glass pearls. We have come late to these crimes, and our viewing is an attempt to reconcile our fear and mourning. When her work is focused on feelings, it has a gravitas that is often missing in the similarly decked out work of her peers, including Radcliffe Bailey, Sanford Biggers, and Mickalene Thomas. When it is not, she runs the risk of creating likeable displays one glances at rather than examining closely.

The installation of …stars… provides a resting place. In this 2018 sculpture, hundreds of women’s shoes and slippers form a glistening black cloud hovering overhead. Patterson is referencing the tossing of sneakers whose laces have been tied together over electrical wires in urban areas to declare gang territory or safe drug dens. In some neighborhoods, hanging shoes signify someone has died. These readings fit right into the artist’s marking of potentially ominous territory and lost bodies. …stars… could be the night sky or it could be a description of the people whose souls have departed the earthly plane.

In …moments we cannot bury… , also from 2018, five large red forms are held aloft by wooden armatures. They seem like big clumps of earth covered in silk plants and flowers, projecting visceral qualities that are both bodily and ceremonial. These mounds invite inspection, and reveal tucked away cast glass objects including hands, toys, baseball caps, sneakers, backpacks, and butterflies. Topping each are translucent flowers of the poisonous variety, including bird-of-paradise, lilies of the valley, and daffodils. We find ourselves in what appears at first to be a welcoming and fertile Eden, only to realize that there is past and possibly present death and danger everywhere.

Last and most poignantly positioned is a small chapel-like room where the video …three kings weep… is playing. Three black men are framed as if in a religious triptych. They are bare-chested and exposed characters who look straight ahead, catching our gaze. They slowly dress themselves, in colorful patterned shirts and vests, jewelry, and other adornments. Their movements are powerfully hypnotic, as much because they are the most vividly alive humans we’ve encountered in the exhibition, as well as the fact that the costumed action is playing in reverse. By the end, each man will be silently crying. At times during the eight-minute video, we hear a man reciting lines from the 1919 poem “If We Must Die†by Jamaican poet Claude McKay. It is a testament to dignity and bravery, and the power and vulnerability of black bodies.

A final comment about Patterson’s use of ellipses in her titles. We know that this grammatical mark is used to designate an omission in a sentence. In many of her works, this serves as a reminder that things have been left out, or are unknown to us, or might be revealed later. It is our job to sift through what is here, carefully accumulating clues, whether we are surrounded by lush foliage or sitting quietly in a spare room.

*The title of my essay for Patterson’s exhibition at Monique Meloche was Garden Breakdown. I’ve altered it slightly for use here.