It’s been a week or so since I visited Mike Goodlett in his sanctuary.

“Sanctuary†is one of those go-to words I never go to, but I’m going to it now, after having experienced its manifestation in real life. Where Goodlett makes art is simply that: a place of refuge, of safety, sort of sacred but also a little scary, like a hiding place you go to in dreams when you are being chased by blurry creatures you may not be able to remember but then wake up and try to draw.

In this case, “sanctuary†is an anonymous farmhouse with a gravel road leading up to it tunneled in trees and vines. The day I visited was all crystal-clear blue sky, a beautifully strange shine on and coming from everything, like a photograph that never gets taken but somehow still is a photograph. The house is white-sided, two-storied, and gray-roofed, with multiple front and back doors, lots of windows, and all around it is yard going off into land, some of it barren, some of it treed, grass just now sprouting into life.

I parked and got out of my car. There wasn’t any wind, just that bright chilly air. Even though I had never been here before, it was like a returning. Meeting Goodlett was like that as well.

He is tall and unassuming, very polite, and we shook hands after I called him on my phone, confused by which door I should knock on. We both were awkward at first, but almost instantly we got down to business. I was here to see his art, and this is where he makes it, so we went on in, an automatic transfer from reality to ghostliness. Nothing unnerving at all about it though. There wasn’t an abandoned-house fustiness, or even a feeling of loss; it was the smell and ambience of lives having been lived, dusty but clean, sunlight baking old wood and plaster into an atmosphere.

“I’ve always wanted to be left alone,†Goodlett said. It was sort of a joke, but I think he meant it as a solemn introduction too.

“I mean, I can’t find a group I want to be a part of. So being out here for me has made a lot of sense.â€

The house is actually his grandmother and grandfather’s. They died 30 or so years ago, and since then Goodlett has used the rooms, and the vicinity, as his studio and headspace, creating batches of artworks made from the humblest of materials (concrete, plaster, thread, ball point pens, pencils, crayons, and spray-paint) but that exude a sophistication that belies the humility of their construction.

Goodlett escorted me through each room of the house, which is gutted mostly, emptied of hominess so it can supply this new form of utility. The wallpaper is shredded at points, but still covers many of the walls in a handsome form of pentimento, like a shirt half torn off. A small black wood-burning stove occupies the middle portion of the house, releasing that warmth and smell from my own backwoods childhood: wood-smoke almost like a cologne. In the kitchen a long table covered in stacks of books, drawing paper, pen and pencils, a coffee urn.

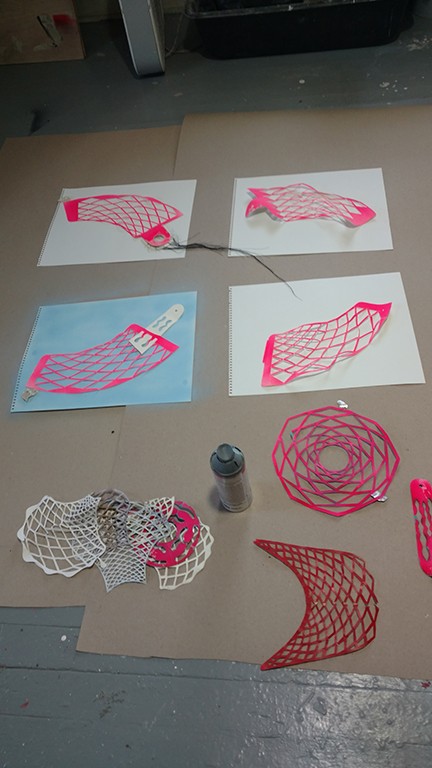

In each of the rooms Goodlett displayed works he wanted to show me. We started out, though, in a cold little side area where he was experimenting with spray paint and cut-out stencil-like netting. There were chunks of sculptures in here as well.

He walked around showing me what he was trying to figure out, and then told me, “I love changing materials, figuring out what they can do for me. Ideas, too. I move from one body of work into another that way. I know a body of work is finished really when I don’t have any more energy for it, and when it has a place to go. Energy and interest are kind of linked that way.â€

This house itself was like his manifesto in a lot of ways: objects and ideas half-formed, trying to find each other. An exuberance flashed out of everything that’s not finished, that was looking for a way to be something else. At one point he showed me some homemade lace he’d constructed from thread, pastel cobwebs shaped into socks and little hats, creepy and droopy but also innocently tattered, as if made to be used by ghosts.

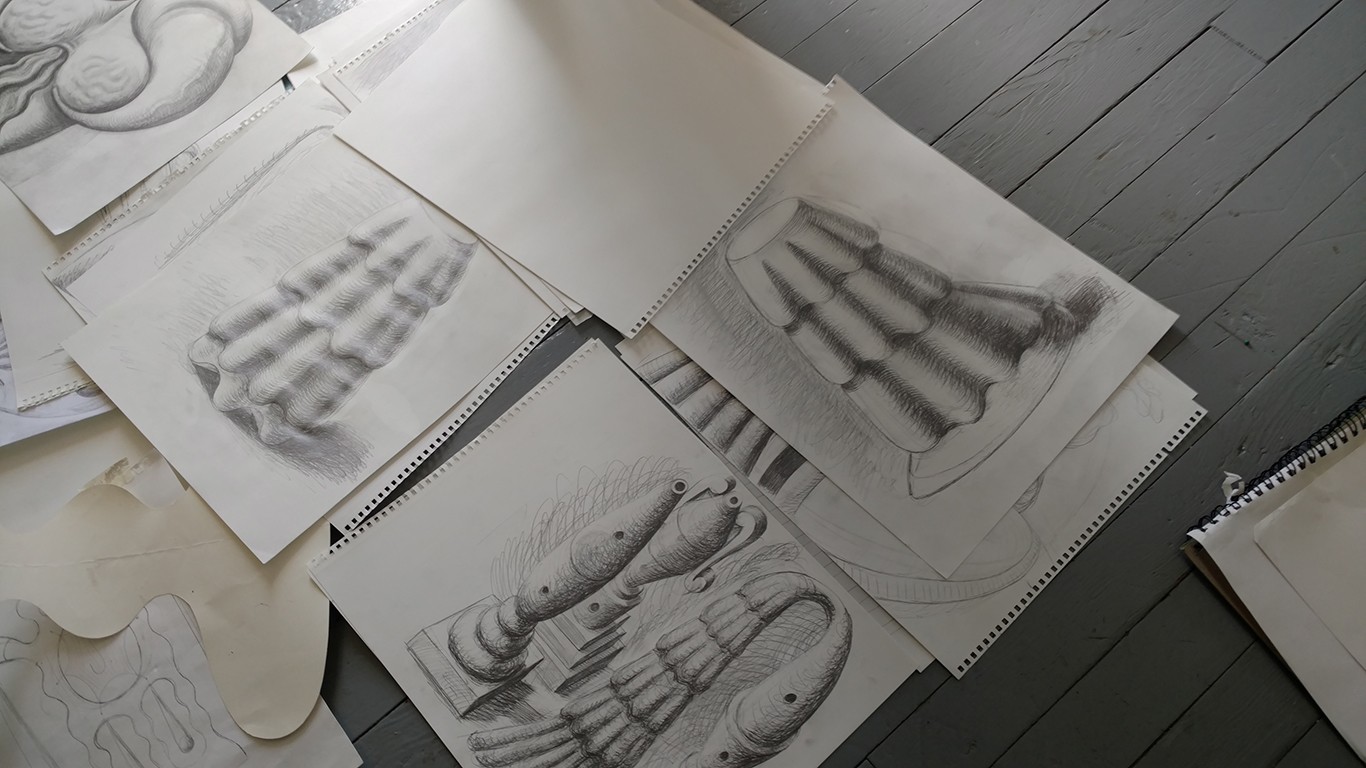

Goodlett walked us through a hall and into another first-floor room, which was crowded with more sculptural works, as well as pages and pages of his drawings spanning across the gray-painted wood slats. His three-dimensional objects have a tenderness you can’t name, concrete/plaster-formed mainly biomorphic and/or humanoid shapes that have evolved from the drawings. And conversely, the drawings often vacuum in the shapes of the sculptures, a sort of aesthetic circle-jerk that reminds you both of angelic visitations and, well, group sex.

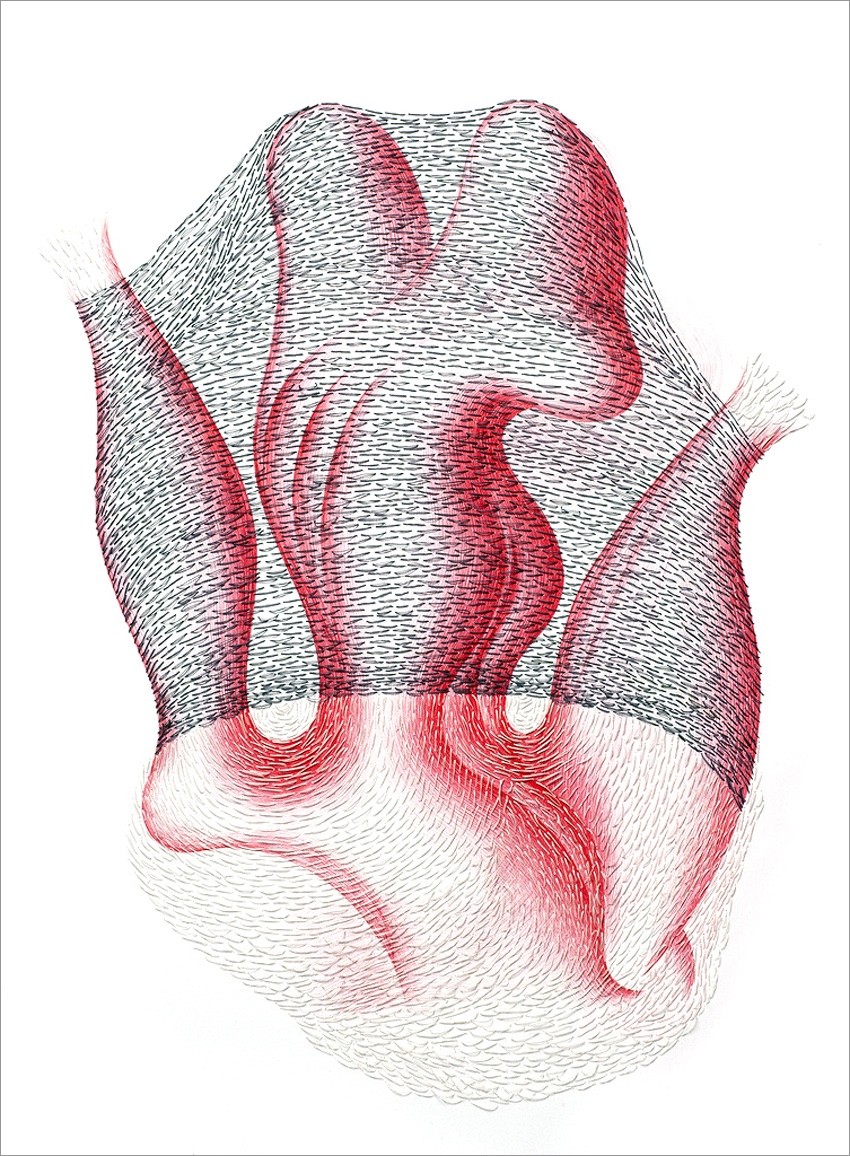

Or, as Goodlett likes to call it, the intersection of “whimsy†and “pornography.â€Â That’s one of his main themes, he told me, a way of trying to figure out the meaning of those two usually unintegrated penchants, often seen as polar opposites. Whimsy in visual art often can become a twee exercise in flirtation, pornography a way to shock or display street cred. The drawings, on paper and cardboard, created through an enmeshing of ink and pencil, needle and thread and paint, get at that merger without losing a sense of vigor and intimacy. They are shapes pulled from gestures and moans that have ballooned into myth. Through that clarification process, whimsy connects to porn, and abstract goes concrete.

In a drawing from 2011 titled “Dress Socks†(from a show called “Dress Socks and Other Diversions†at Institute 193 in Lexington, Kentucky), Goodlett gets down to the whimsy of porn and the porn of whimsy through a delicate fetishization of everydayness. It’s an abstracted image of socks, given a veil of obsession, but a delicate ritual line informs every aspect of the drawing, like a Spirograph finding its way to language. The drawing’s beauty comes from Goodlett’s dedication to finding what makes something erotic when it is not, what makes something endearing when it’s just an object you slide your feet into. That investigation is done without words but through an adherence to what drawing can mean and do, a visual language that does not ever need a thesaurus.

We went upstairs.

Witnessing all of Goodlett’s rooms on display in his own personal museum up on the second floor, I kept thinking of Philip Guston’s jazzy delinquency and Georgia O’Keefe’s penchant for curves – all of that aestheticism laid bare through a need to make something personal, to find relief. Throw a little Dichirico in there too, especially when taking in Goodlett’s objects: that stony sense of stillness matched with a yearning for songs of love.

In a piece I saw in one of the rooms, “Untitled†(from the 2015 exhibit “Human Behavior†at the John Goodlett Kohler Art Center), the connection to all of the above references comes through clearest. The shape is chandelier crossed with internal organs, all of that turned to stone and then clothed in gauzy spandex, like something a mummy-stripper might put on to take off. The muted color gives it dreaminess and pallor, but also highlights the stalagmite seriousness of its existence. The solidity of it is an elegant joke too, like a lead balloon, but also you feel enlightened by its sense of holiness somehow. It’s something you might worship, like an Egyptian artifact after the fact.

Goodlett mentioned Osiris in this room upstairs. The Egyptian-ness of his pursuit.

“It’s like inviting something supernatural to come and visit,†he said. “Like I’m making vessels to contain them.â€

One of many Osiris’s many identities is “Lord of Silence.â€Â He also goes by “Ruler of the Dead,†probably the first Egyptian deity to be associated with the mummy wrap, containing the dead in supernatural fabric to protect them as they made their way out of themselves.

Goodlett also explained to me that he works in cycles. Each cycle gets determined through exhaustion and external deadlines. He is constantly pursuing obsessions, materials, and subject matter with an eye toward perfecting what he can, reinventing what he invents, and repurposing what he gets rid of. (Right beyond the back porch is a beautiful pile of tossed-aside concrete and plaster pieces, a little encampment of future shapes, ideas, connections.)

In each room upstairs, drawings and sculptures waited for us politely, leaned up against the walls, ready for whatever. My mind went to J. F. Sebastian from the movie Bladerunner. He’s the genetic engineer left behind on Earth after most people have gone to colonize other planets, and because of dystopian loneliness and boredom he creates a generation of toys and androids to help him feel a little less alone.

I’ve always considered J. F. Sebastian a beautifully realized portrait of an artist without the normal baggage associated with “being an artist.â€Â His connection to what he makes is sincere and real, and yet he also understands the purpose of his practice in a pragmatic, unadorned way. He needs to make things in order to have someone there at the end of the day to greet him, to break away from a world that may no longer be there for him. He creates an ecosystem out of bits and pieces, and in a movie filled with bleakness and doubt his existence feels the most hopeful and ironically the most grounded.

At one point, in one of the rooms upstairs, Goodlett brought in a bunch of drawings and laid them out on the floor, an overwhelming overspill. You could tell he doesn’t like to talk about his work until he starts talking about it. But once he got going, he seemed relieved to be able to say what he wanted to say.

“Solitude appeals to me,†he said. “But I also know I need to have a place for all of this stuff to go.â€

He mentioned Philip March Jones as one of those external factors who’s assisted in understanding where he might fit in the world outside of here. Jones, funder of Institute 193 and currently its Curator-at-Large, visited Goodlett here ten or so years ago and would not take no for an answer after asking Goodlett to have a one-man show. Now dealers and curators often come to him.

All of my talk about J. F. Sebastian and solitude and sanctuary might make you consider Goodlett an “outsider artist.â€Â I truly hope not. I don’t really think those old-school rules of arbitrary classifications apply here or basically anywhere now. Goodlett graduated from an art school in the 1980s (Cincinnati Art Academy), and he has had exhibits at a lot of high-end joints, write-ups in national media (BOMBmagazine and Artforum, just to name a couple). His outsiderness really is not something to focus on or to conjure. He is an artist living his life, using what he makes to keep his life and energy and interest going.

At the end of our visit Goodlett told me he had to go to the grocery store next. He explained how he’s one of the only family members left who can take care of his elderly mom and his aunts. He spends a lot of time making sure they are doing okay, and then he comes out here to pursue what he needs to pursue.

This farmhouse from his childhood is not Paradise Gardens, or a version of Watts Towers. It’s just where he has wound up. Somehow the journey and the destination have merged into both an artistic practice and a reason to live. Making art, whoever is making it, weaves the inner-world into the outer-world in a way that allows you to recover and replenish and continue. This rooms in Goodlett’s farmhouse are always evolving, changing, and he always struggles to figure out what fits where. What drawing can give birth to three dimensions, what object can be sucked into two. This space has given him permission to do the work he needs to do: making clothes for ghosts, making ghosts so he can make clothes for them.

“I guess you’d call everything I do part of an ongoing installation that never ends,†he told me.

Eventually, we went outside and did a little tour of the yard and surrounding area. Just beyond his front yard is a thicket of tall trees where he’s installed a couple of sculptures. One of them, sprouting from the mud like the hardened teats of a buried cow, is the perfect example of whimsy sliding into something a little less than charming and more guttural. It’s ridiculous but also makes perfect sense.

Goodlett’s pursuit of art is converging the need to be seen with the need to disappear.

Right before the end of our visit, Goodlett talked about his legacy in terms of where all this work might go. He told me he had a dream that he would have all of his works stored in an anonymous storage shed, and he would give the key to someone, right before he passes. He smiled.

“The only problem is – who do I give the key to?â€

I nodded my head. We said goodbye.

The night before visiting Goodlett, I went to an Iron and Wine concert, so I was playing Iron and Wine songs all the way here and all the way back. When I arrived, and when I left, the song I was listening to was “Resurrection Fern,†from the 2007 album The Shepherd’s Dog. The music is steel-guitar languish blurring into folk-rock lament. Sam Beam’s voice has a cadence and warmth to it, like a voice you hear only inside your head when you’re dozing off in church.

“Resurrection Fern†starts with these words:

“In our days we will live

Like our ghosts will live

Pitching glass at the cornfield crows

And folding clothes.â€

I won’t be able to hear that song now without thinking about the depth and amount of Goodlett’s work, the place where he makes it, and the life he’s lived in order to be able to do it. There’s a poetry to his pursuit you can’t write poems about; you can only acknowledge his lifelong project by knowing his work is a journey toward making more work, and more work, until all of it will need to a final place to exist – a pyramid, a museum, a storage unit, or a haunted house. It doesn’t matter. Wherever it all goes it will be called “home.â€