“In Heaven Everyone Will Shake Your Hand: The Art of Julie Baldyga,” a book of the Louisville artist’s work published by the Louisville Story Program, was scheduled to be released at the opening of her solo show at KMAC Museum on April 17, 2020. Instead, books were shipped to those who had ordered them and who were now hunkered down at home during the pandemic-prompted lockdown. I vaguely remember enjoying a quick perusal of the book when it arrived, though admittedly it was soon covered up by other mail and forgotten amid the fresh anxieties that were threatening to bury everyone during those first quarantined spring weeks.

This is not any indication of the book’s quality – it is indeed a wonderful volume filled with more than 150 works from a career spanning nearly five decades, complemented by personal photographs of the artist and interviews with Baldyga’s friends and family. But I merely want to emphasize, for those who have not yet ventured out to discover this for themselves, after months of having my art consumption rationed to its digital forms, that the experience of viewing “Julie Baldyga’s Heavenly People†in the third-floor gallery of KMAC Museum was nothing short of ecstatic.

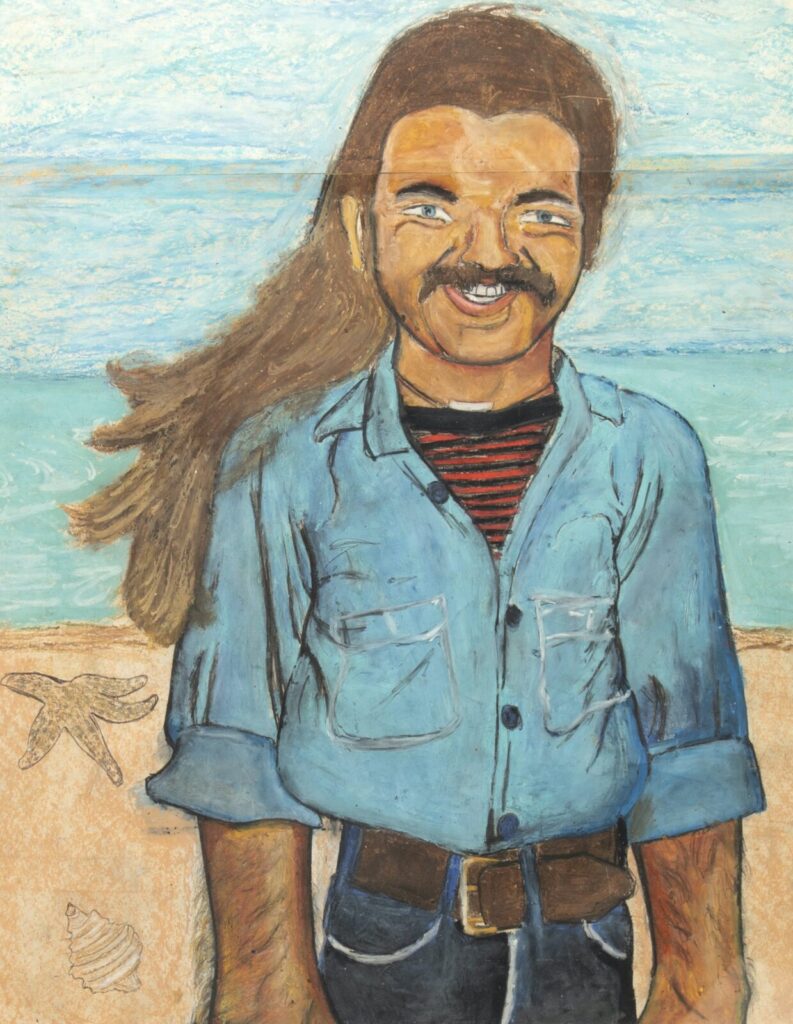

I choose the word ‘ecstatic’ because there is a religious quality that permeates all of the works in the show. Perhaps it had something to do with staring into a stranger’s unmasked face for the first time since March, but standing in the empty gallery in front of Billy on the Beach in California, I found myself incredibly moved by this almost Christlike figure, his long, sandy hair blowing in the ocean breeze, a beatific smile across his tanned visage. With oil pastels, Baldyga deftly renders the folds of her subject’s chambray shirt with the same devotion to detail that older masters dedicated to the robes of religious icons. Encircling Billy’s head, her skillful blending of the tricky medium creates the faintest of halos against an azure sky.Â

The work is one of few in the show – comprising more than a dozen of Baldyga’s pastels, along with several ceramic and soft sculpture works and six of her titular heavenly people — in which human hands are not a prominent focus. In Hadley, another early work, Baldyga portrays her subject (a friend of her brother Philip) from behind, obscuring his face entirely but allowing us to see, in magnified proportion, his hands held open in offering behind his back. Note what Baldyga chooses to detail: the machine stitching on his tennis shoes and the back pockets of his jeans, the veins threading down his forearms like the wires might attach to pistons.

“Most of us rely on the face as our essential point of contact,†notes curator Joey Yates. “It is often the primary way we communicate with one another. But for Julie, that point of connection seems to start with the hands. The detail and emphasis on hands are often the expressive center of her images.â€

Combined with her penchant for portraying subjects from behind, this distinct perspective was what first drew Yates to Baldyga’s work, seeing it as “a portal into a particular vision of the world.†Nonverbal until she was seven years old, the artist expressed herself through drawing from an early age, a talent that her parents and her teachers at the Binet School (which she attended for ten formative years) enabled to flourish.

As a teenager, Julie began working in oil pastels, teaching herself how to blend pigments with her fingers and add depth and contour to her pieces. Her obsession with mechanics and technology was nurtured by her father, an MIT graduate and chemical engineer, who not only entertained all of Julie’s technical curiosities, but also supplied her with the wires, tubes and hoses she employed in early sculptures, along with the instructional manuals, model engines and spare parts that she recreated in drawings and ceramics.Â

Women in engineering are a favorite subject of the artist’s, such as in the delightful Elizabeth with a gas engine in her puff shooting smoke. Like Billy on the beach so many years before, Elizabeth’s long, lustrous tresses (her “puff,†in Baldyga’s lexicon) are swept to the side, this time occupying enough of the canvas to make it a horizontal work. Dark curls of hair swirl around a gas engine, their curving lines echoed in the undulations of smoke emanating from the motor: mane and machine are happily one.

Even more resplendent is the 2014 work Kissing Fish, in which the female subject is surrounded by lush palms and verdant grasses with small clusters of pink tulips while amphibious creatures with long arms and human hands tenderly pick at the young woman’s hair (her puff!). These two pairs of creatures have human hair, too, of course, and their hands and arms mirror each other in beautiful symmetry, reminiscent of a wondrous, Chagall-like space in which humans and animals float through joyful skies.

“Julie has invented her own world,†Yates says. “It is not only a place she can escape to, but also a world that she invites us, as viewers, into as well. In those moments when we want to turn away from the chaos around us, we rely on visionaries who can guide us to a respite from harsher realities.â€

It is a curiosity, then, that the show’s namesake pieces – life-size representations of Baldyga’s friends that she creates out of found materials in the belief that they will inhabit these forms when they go to heaven – embody the idea that perfection is something achieved only in the afterlife. Because if we are to see our own world as Baldyga sees it, to view everyday objects with extraordinary reverence and regard ordinary people as subjects worthy of a visual hagiography – imperfections and all – then that seems like the sort of heavenly world in which I’d want to live.

“Julie Baldyga’s Heavenly People†is on view at KMAC Museum through November 8, 2020. KMAC Museum is located at 715 West Main Street, Louisville, Kentucky and is open Wednesday-Sunday, 10am-5pm.