I first became aware of the artist Tim Portlock when I reviewed the Great Rivers Biennial at the Contemporary Art Museum (CAM) St. Louis in October 2020. Then in its ninth edition, the Biennial had been designed to recognize visual artists in the greater St. Louis area. Portlock, along with fellow St. Louis-based artists Kahlil Robert Irving and Rachel Youn, had been selected by three independent jurors after studio visits with a field of ten semi-finalists. His exhibition, “Nickles from Heaven,†which included eight large-scale archival pigment prints, proved to be the true anchor of the show, offering a mature, nuanced, and often funny response to the uneven development that has shaped cities like Louisville and St. Louis over the past decades.

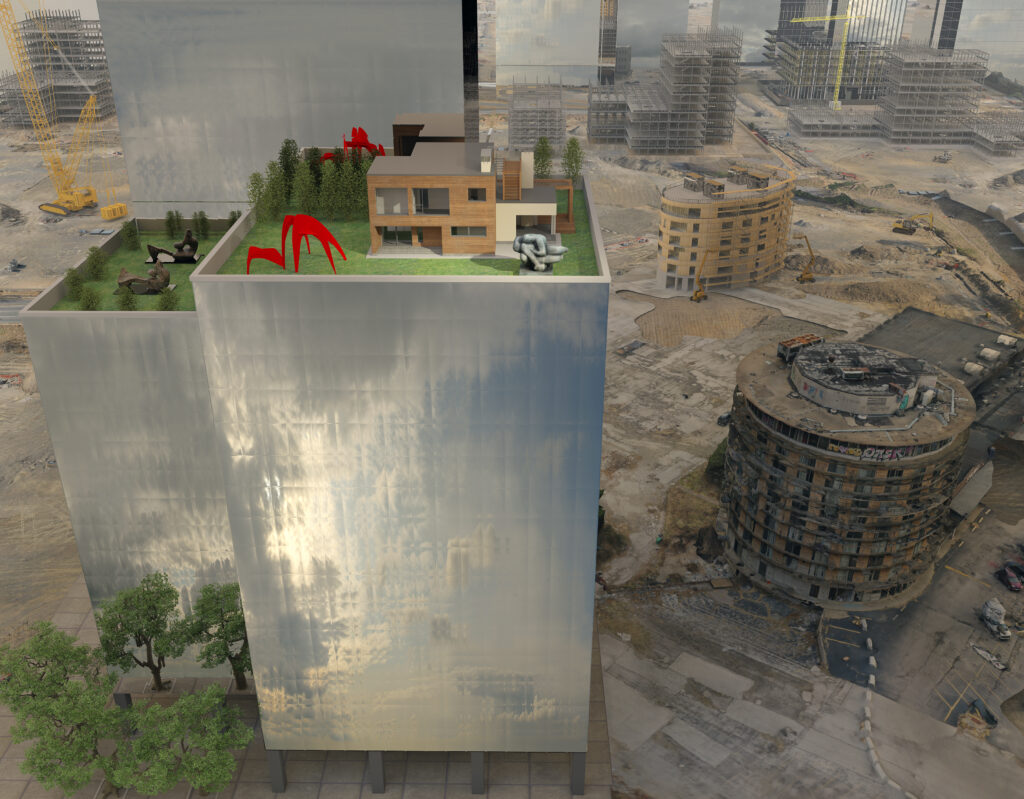

With the use of increasingly sophisticated digital technologies, Portlock creates renderings of fictitious construction sites based on blocks of St. Louis and other peripheral U.S. cities where he’s spent a significant amount of time. His renderings of luxury high-rises radiate with the golden light of 19th-century American landscape painting, while derelict buildings stand adjacent, already crumbling as if in anticipation of their imminent destruction. Portlock’s cities are devoid of people, the few glimpses of human presence coming with a satirical touch: the modernist art collection atop a gleaming condominium in sculpture garden, the manufactured wilderness (complete with deer and bison) on the rooftop of another shining starchitecture example in unrivaled – two pieces I saw in the Biennial that felt especially appropriate to St. Louis, America’s erstwhile Gateway to the West.Â

I was able to speak with Portlock in August 2021 via Zoom during a break in his teaching schedule at Washington University. We discussed the effects living in St. Louis has had on his artistic practice, as well as his thoughts about the state of contemporary art in the Midwest. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Natalie Weis: You were born and raised in Chicago, you’ve lived and worked in Paris, New York, Philadelphia and now in St. Louis. Can you give me a brief overview of your career and then tell me what attracted you to St. Louis?

Tim Portlock: I started out as a painter. I have an MFA in painting and was showing with two galleries, in addition to painting outdoor public murals as a side gig. Then, in the late 1990s, around the time the internet was coming into popular use, I got into digital technology as both a medium and as a tool to make art. I went back to school and earned another MFA concentrating on virtual reality projects. I started to get into real-time 3D graphics and I stopped making art for a little bit. I worked for the University of Paris for a couple of years, making historical simulations of areas of Paris, and then I came back to the United States and took a job teaching at Hunter College in New York, where I worked for 11 years.Â

At Hunter, I started making art with the same kind of tools I had used to do the historical simulations, but I began referencing the conventions of 19th-century American landscape painting, using that as the visual organizing principle of the imagery I was creating. At the same time, I was using contemporary cityscapes as a subject matter. I moved to St. Louis in 2016 to teach at Washington University. For me, it feels like a very small city. Before that, Philadelphia was probably the smallest city I had lived in and then I felt like I dropped several tiers, size-wise, to St. Louis, which has a population of about 300,000.

I arrived at an interesting time in St. Louis in that there were a lot of other people who were relatively new to Wash U, who had come through the 2008 economic collapse and looked at St. Louis as an opportunity for making art and as an environment where you could really make an impact. One of the things I had enjoyed working in Philadelphia was that there was a big D.I.Y. artist collective scene. There are very few commercial art galleries here, but there’s a robust artist-run space scene and I thought St. Louis was fertile ground to build up that infrastructure, so I was really optimistic about that.

NW: Was there anything you found surprising about the St. Louis art scene?

TP: The St. Louis art scene is still pretty small, but I do think there’s a contingent of people who are plugged into the international art scene in a pretty significant way. There is a dialogue happening that I would maybe even go as far as to say is on a global level. We have The Luminary, and its founder goes to international conferences and he’s become pretty well known. He brings in artists from all over the world. I’ve met artists in other parts of the world and then seen them again in St. Louis at The Luminary. So that has surprised me a little bit.

There are also a couple of artists who have very quickly become a part of the international art scene, and a handful of international artists who live in St. Louis that few people know about. I only found out because I sat on a jury panel for the Public Art Commission and some of the proposals were from artists who had shown at Art Basel and other international art fairs. I saw they were living in St. Louis and I thought, “Wow, I don’t know about this.†There is also a quiet but very serious collector base in St. Louis.

NW: How do you see St. Louis in relation to other cities you’ve lived in, such as New York and Paris, that the world regards as major art centers? For instance, do you perceive there to be more or less collaboration among artists, or a significant difference in the number of opportunities for artists to show and be seen?

TP: I feel like curators are a lot more accessible in St. Louis and in Philadelphia as far as socializing, such as at parties and openings. People in smaller places that are not as connected to the international art circuit are probably a little more motivated to figure out ways of plugging in through artist residencies and travel. Though in the Midwest, it’s a little harder to do that. If you’re on the East Coast, the big cities are only about an hour and a half from each other, whereas in a place like St. Louis or Louisville, the next big city is more like three and a half or four hours away.

Outside of the commercial gallery sphere, I do think a lot more artists are looking at artist collectives – not only participating in their own, but also looking at the network of artist collectives around the country and taking advantage of that. I was a member of Monaco and one of the things we put a lot of effort into was organizing exchange shows between collectives. We would show at, say, a collective in Chicago, and the collective in Chicago would show in St. Louis. We did the same thing with an artist collective in Manhattan. That strategy of getting the work out is something I’m seeing in a lot more non-top-tier cities, and I feel like it’s enabled a lot more to happen in smaller towns. Even Little Rock, Arkansas, has a pretty interesting art scene as a result of that, and it’s gotten visibility in other parts of the country.Â

NW: Have you seen any shift in how cities in the Midwest like St. Louis or Louisville are perceived by curators and critics in New York and L.A.?

TP: I hate to say it, but I feel there are several different registers to the art world: there’s the upper register where you still need to have a degree of physical presence in New York and Los Angeles to participate. And then there is the lower register – the more D.I.Y. scene with the art exchanges I’m talking about. If you choose to have that kind of career as an artist, you can stay in that D.I.Y. space that’s like a national network of local scenes. Or you can move up to that upper register, to the top-tier, blue-chip network of galleries. But I don’t think that people from L.A. and New York are thinking of St. Louis as the place to be. It’s actually a lot of work and a lot fewer opportunities to be in St. Louis as an artist.

One of the things that spurred me to transition from being a painter to making digital art was that, for a period of time, I was really fascinated by the Internet as a more democratic art distribution network. Of course, that was the late 1990s when there was a lot of idealism about the internet – making art accessible to everyone regardless of physical proximity, and making New York City and other art capitals less necessary for a serious art career. And that didn’t really work out. [laughs]

NW: And why do you think that was?

TP: There are other factors that people couldn’t name at the time that go into the continued existence of major art centers, like the importance of physical proximity. When I got the job at Hunter, I was living in New York City and finding it really difficult to get into the art community there. I remember meeting up with a friend from undergraduate school who owned a gallery in Chelsea, and he pulled me aside and pointed to different clusters of people in the gallery, saying, “You see that group over there, that’s the Yale Group. You see the group over there, that’s the Columbia group.†And I thought, “Oh, I get it now.†There’s still that kind of pedigree or association that’s so important.

These institutions are also in close proximity in New York, right? Critics can go to the studios at Columbia University and get familiar with artists before they’ve even graduated. I feel like curators are more accessible in smaller cities, but a little bit later in artists’ careers. You don’t have them showing up to a grad critique.

NW: Do you see anything that could help cities like St. Louis or Louisville strengthen their art communities?

TP: I don’t know if I’m just indoctrinated, but I wish there were more artist-run spaces. Artist-run spaces come and go, they fail all the time, but I don’t think that’s a failure of the model. They should just come and go in a lot of cases. But what I like about them is the sense that you are taking control of showing your work and you’re not reliant on some benefactor to come in and create the conditions for other people to see your work. I wish there were more of that.

I think there is a sort of an entrepreneurialism to artists I know in St. Louis, in terms of getting commissions to do public art, for instance. But we could have more artist collectives, those physical spaces where people can come together as a community and talk about things. And there are a lot of different ways of modeling that, which could reflect different philosophies about art. The non-profit model is just one.

NW: How has living in St. Louis influenced your artistic practice?

TP: I’m totally conscious that, in a way, I’m trapped in my own network here. I’m a Wash U professor and I tend to interact with people who orbit around it as the big institution in the city. There are a lot of things I don’t know, but I do feel like I have a sense of the things I don’t know, to quote Donald Rumsfeld. [laughs] The known unknowns, right?

For example, I know there is a whole other art scene in North St. Louis. I have a friend, Gavin Kroeber, who relocated to St. Louis about a year before I did. He was in the hierarchy at Creative Time, and because he’s a curator and produces exhibitions, he was much more systematic about getting to know the city, and I learned a lot about St. Louis from interacting with him.

In 2018, he and I organized a symposium called Dwell In Other Futures, focusing on different communities’ ideas about the future of the city. Gavin was able to find the widest range of artist communities from St. Louis, including the more D.I.Y. North St. Louis art scene. So there are definitely other things going on besides the MFA-driven, professional art scene that I’m a part of.

NW: Your work often focuses on patterns of decline and gentrification and the sharp contrasts that can exist in the physical infrastructure of cities. Has St. Louis influenced the subject matter of your work?

TP: The decline of St. Louis definitely fits into the things I’m interested in regarding the subject matter of my work. There’s also the weird phenomenon that’s going on in every city where there’s a weird amount of development and property value inflation happening at the same time. But St. Louis isn’t growing in population, so that seems very strange to me.Â

In each series of work I’ve done, I’ve tried to come up with a strategy for getting input from people in the city that I’m focusing on. I’ve made bodies of work about Las Vegas, Nevada; San Bernardino, California; Camden, New Jersey; and Philadelphia. I wanted to do a new series of work about St Louis, but I relocated here immediately after the Ferguson shooting and people were very sensitive to media depictions. I realized very quickly that my talking about St. Louis and still being an outsider was going to be uncomfortable. So even though I came to St. Louis wanting to interview people and make work incorporating their ideas about the city, I’ve held off on that. Since I’ve been in St. Louis, I actually haven’t been making work about any specific city, but more like the idea of the American city.