“Hobo # Birdman†at Institute 193 is a show that gives us beautiful glimpses into the personal world of Joe Light. The artist who, after much travel, made his home in Memphis, Tennessee, died in 2005. His work is in a number of major collections around the United States, most notably the Arnett Collection who collaborated in bringing the show to the Lexington audience. The paintings on view are direct and playful, full of bright colors and everyday media of house paint and discarded wood. When I stood in front of the work (the gallery is open, maximum capacity of five, bring your mask), I was instantly presented with an image of an artist driven by the inner need to get the work out into the world. Here the paintings present themselves not as cerebral academic exercises but as direct streams of consciousness that dare the viewer to react. Name your emotion. Push it forward. Dance with it. Sing it. Make it your own.

When situating the work within the narrative of Joe Light’s complex personal history, one realizes just how much of the spiritual core of his work is reflected in it. His story, early struggles with family, several incarcerations, conversion to a self-constructed version of Judaism that initially prompted prison authorities to place him in a mental health institution, and the eventual construction, through his art production, of a sacred space around his house, speaks to both the transformation of an individual and the uniquely American context of racial segregation and syncretism. “Renouncing the Baptist Christianity of his youth, he developed a personal faith conditioned by the racial prejudice he experienced in the pre-civil rights era South, as well as suspicion toward Christianity’s effects on colonized peoples,” states Gerard Wertkin in the Encyclopedia of American Folk Art.

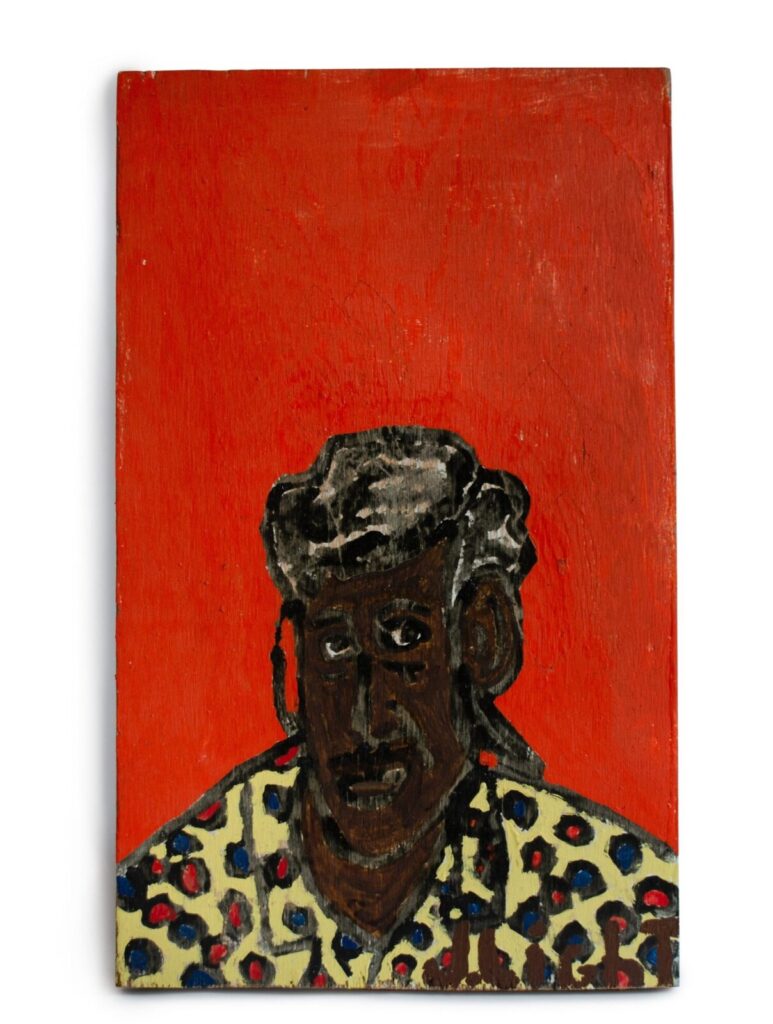

The artwork that comes out of this context is split into two bodies, statements written on yard signs (not featured in the show at the Institute) and paintings on found materials and architectural structures. Both point to a set of deeply personal religious convictions that were rooted in Light’s interpretation of the Old Testament and navigation of his own identity as a descendant of both Africans and Native Americans. His figures are quite intentionally multi-colored and, in the case of the Birdman cycle of works, refer to the universal nature of his spiritual project. It must be noted that he perceived this “universality†through direct experiences and ancestry of his own body. This is not a generalized message of unity but rather one that leads with the internalization of life experience and its transformation into a life work of an artist.

The Birdman, one of the namesakes of the show’s title, is an image of a human with a bird on their head. This has personal significance, as a bird flew into the window of Light’s jail cell during his conversion experience. The artist described the event the following way:

“I said, ‘If you’re God, prove it.’ He said, ‘Step up to the cell door and I’m going to let a bird land on that window sill, and you take control of him. Tell it what to do and it will do it.’ And sure enough, the bird landed on it.”

The bird becomes quite literally a symbol of the divine in Joe Light’s work. It is important to note that in the artist’s self-portrait there is a space left for the bird to land on his own head as if to tell the viewer that he is indeed waiting for his personal enlightenment.

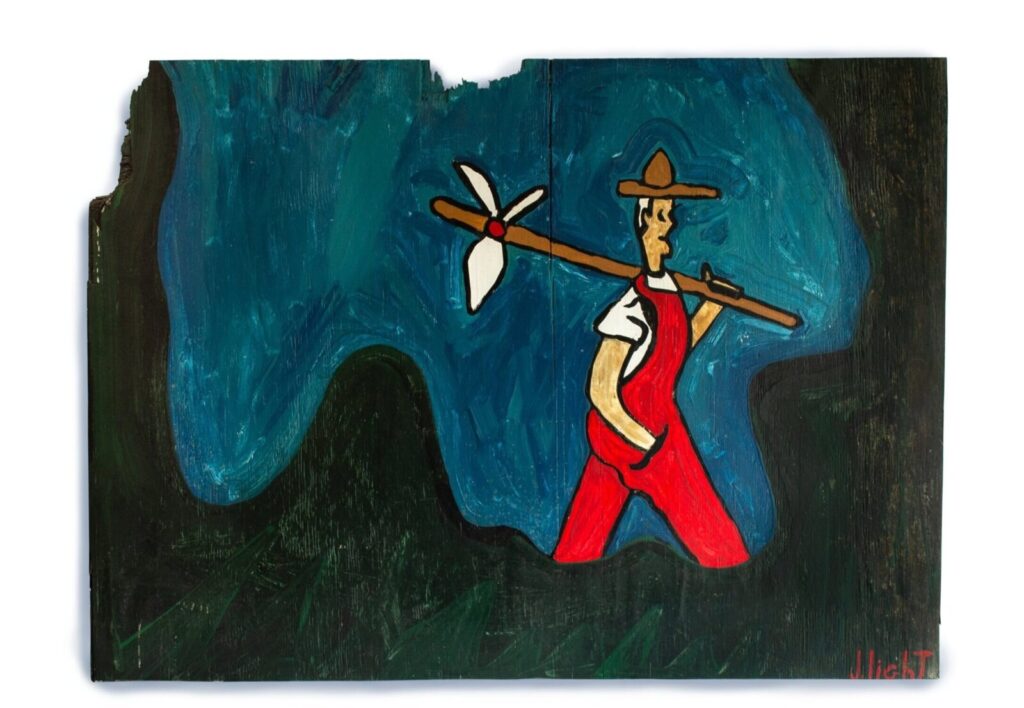

Another image that hovers in the space between an archetype and a personal symbol is that of a traveler, or Hobo. The traveler evokes mythologies from Mercury to Eshu and readily references Light’s own wandering days. This journey can be a spiritual one, leading us to the Promised Land of the Old Testament, or one that navigates the complex socio-economic landscape of the American South. Regardless of the setting, the Hobo becomes a visual focus of the narrative constructed by the viewers; deserving of our empathy, and seemingly ready to sit down and tell us his story.

Each of the images described above repeats over and over again in Joe Light’s body of work. I find myself inevitably drawn to music metaphors to describe this visual experience – a way to translate the authentic reimagination of the pop culture by a Black American pushed outside the boundaries of the dominant culture. These recurring visual motifs are very much akin to blues licks – recast, reinvented, reshaped by life experience. They rely on soul and imagination; slight variations on color or duration of a note speaking to more possibilities than a symphony. Here the direct pulse of the work allows us to enter into a dialog with a unique vision of the artist and the sanctuary that he built to his version of the sacred.

All images courtesy of Institute 193

“Joe Light: Hobo # Birdman”, is on view at Institute 193 in Lexington thru July 31st.