It’s an overcast Monday afternoon when Mia Cinelli opens the front door to her home with a welcoming smile. Situated on a tree-lined side street a few miles from the University of Kentucky in Lexington, Cinelli’s home provides a space to work away from her on-campus studio, which she concedes is presently serving more as an office than a creative space. Cinelli came to Lexington in 2017 when she accepted a position as Assistant Professor of Art Studio and Digital Design at UK’s School of Art & Visual Studies. Prior to her current position, she was appointed by Defiance College (Defiance, OH) to launch a new design program while concurrently serving as the college’s gallery director, positions she was offered directly following the completion of her MFA at the Penny Stamp School of Art and Design at the University of Michigan (Ann Arbor, MI).

Cinelli is an artist, designer, educator, and a proud “Yooper,†a native of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. She pulls her hands up to her face to mimic the mitten-like geography of her home state, pointing out with a grin that Yoopers come from the left hand, the sliver of state connected to Wisconsin that is separated from the rest of Michigan by the Straits of Mackinac. Speaking about her connection with the region, Cinelli is almost wistful, “The Midwest, I think, is more like a deep personality trait, as opposed to a place, and the U. P. is especially weird. It’s really an esoteric culture of flannel and mining and logging. Something I miss kind of deeply…in the winter everyone says ‘stay warm,’ that’s the sendoff everywhere, but I always liked that as a Midwestern thing, like the Midwest is warm, it’s cold in terms of its climate but it’s warm in terms of its people.†It’s obvious that Cinelli is concerned with people, especially within her creative pursuits. In her studio work as an artist, Cinelli’s output asks us to consider, reflect, attune. As a typographer and a designer, she’s working toward clearer forms of communication and deeper methods of expression.

For Cinelli, aspects of function, intention, and context are intricately interwoven, which can blur the line between art and design. She sums it up in this way:

When I was in school I remember reading, “design is art with function,†which was the boiled down version of the saying, and as I got older I was like, “I think that’s kind of a bullshit answer,†because art has function, too. I don’t think that’s the delineating kind of thing…clearly it all has a function, they just have different functions and they have different kinds of context…but it has to be intentional, it has to be thought out. A function can be a totally emotional experience, it can be a function on behalf of the person making it, or it can be on behalf of the people who are seeing it.

There is an atmosphere of awareness that surrounds Cinelli, with attentiveness informing process and practice. She acknowledges that she’s striving for awareness, and that having a background in design aids in the endeavor, relating, “So much of what you do in client work, or in the process of design, the making, the figuring out, the failing, all the good stuff that gets to the thing that gets made, all that process, so much of it is about being able to clearly figure out what it is you’re trying to do and how it is you’re going to do it, and then communicating it to someone else…so that, I think, is about explaining intention and trying to kind of match intention to what it is you’re trying to do.â€

This carries over into her approach to exhibiting contemporary art as well, understanding that exhibitions function as designed experiences. Cinelli posits:

How does someone move through this [exhibition] space? How does someone learn about something in this space? How do you scaffold information or format the art in a way…how do I frame an experience intentionally so that what I want to happen happens, or that there’s at least a chance for that to happen? Because you can never control how the work is received, that’s never going to happen, but you can kind of set up the parameters you want and you can use space effectively to say “okay, what information do we have, how does someone absorb it, or not, and then how do they leave this room different from how they walked in?â€

This desire to impact audience members and elicit change is palpable in Cinelli’s practice. Her work can be divided into three broad categories of inquiry, which often overlap: Language and communication, memory and history, and corporeality, or the body itself. Speaking toward the overlap, Cinelli pinpoints an overarching unifier, “I think a lot of my work is about longing; even the work not about memory, I think is still about longing, either a longing for something to exist in the world that doesn’t, or a longing for something else…it’s something I have a hard time articulating for myself, except that those seem to be the experiences that stay with you, they seem to be the things you carry around….â€

As an artist and a designer, Cinelli is seeking to solve problems, so a certain sense of longing is absolutely vital in her work. No one sets out wanting to change the status quo, whether in a practical or ambitious way, without first identifying a specific problem or set of circumstances to initially address. There are always changes that need to be made, paradigms that need to shift. And if catalyzing change is what your work is about, then a sense of longing belongs there.

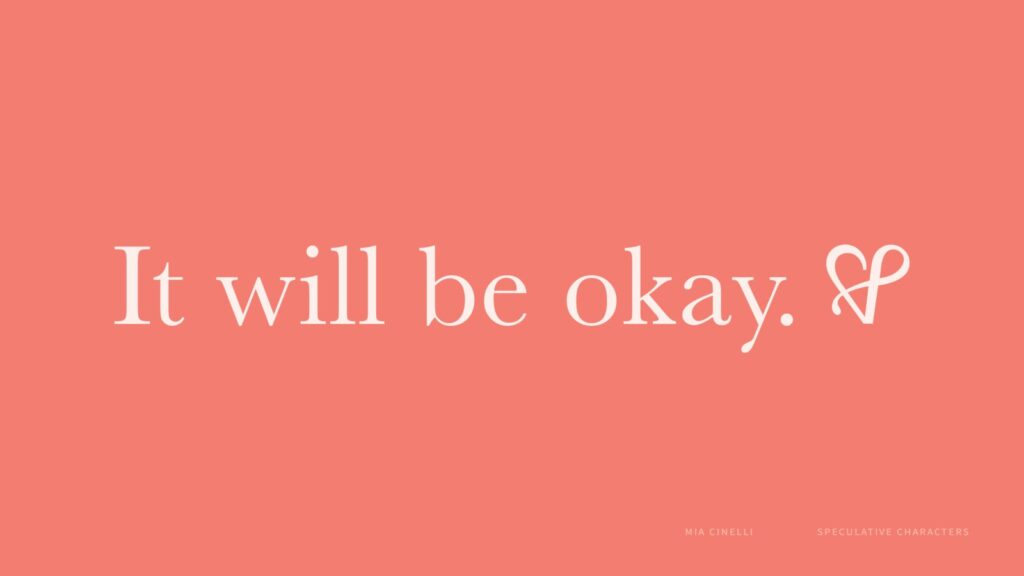

Take her Speculative Characters (2019) series, for example. On her website, Cinelli offers the following explanation for the works:

In the age of emojis, type and image work in tandem to bolster our typographic voices, conveying our wide range of emotions. What if, in lieu of relying on smiley-faces and eggplants to make our point, new punctuation could formally articulate meaning through gesture and expression? Much like [how] written music relies on specific symbols to designate key, volume, pacing and pauses, I believe new letterforms—inspired by facial expressions, hand gestures, and metaphors—could better inform our visual inflection. These new characters are proposed to supplement our existing typefaces, attempting to make the rich complexities of verbal (and nonverbal) conversation visible.

Here, Cinelli has outlined a reason for her longing, a desire to more closely align verbal, physical, and textual communication. And it’s not just a longing on the artist/designer’s behalf. People often ask Cinelli where they can get the characters, if they can download them, if they’re available for mobile phones, underscoring that there is a larger desire for these kinds of expressive marks.

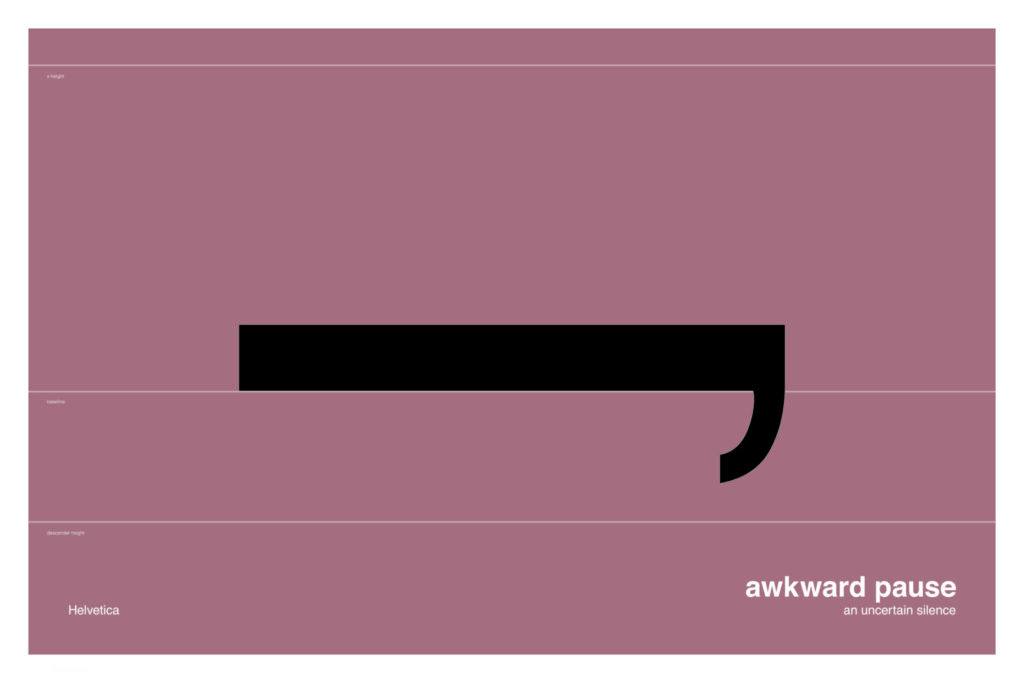

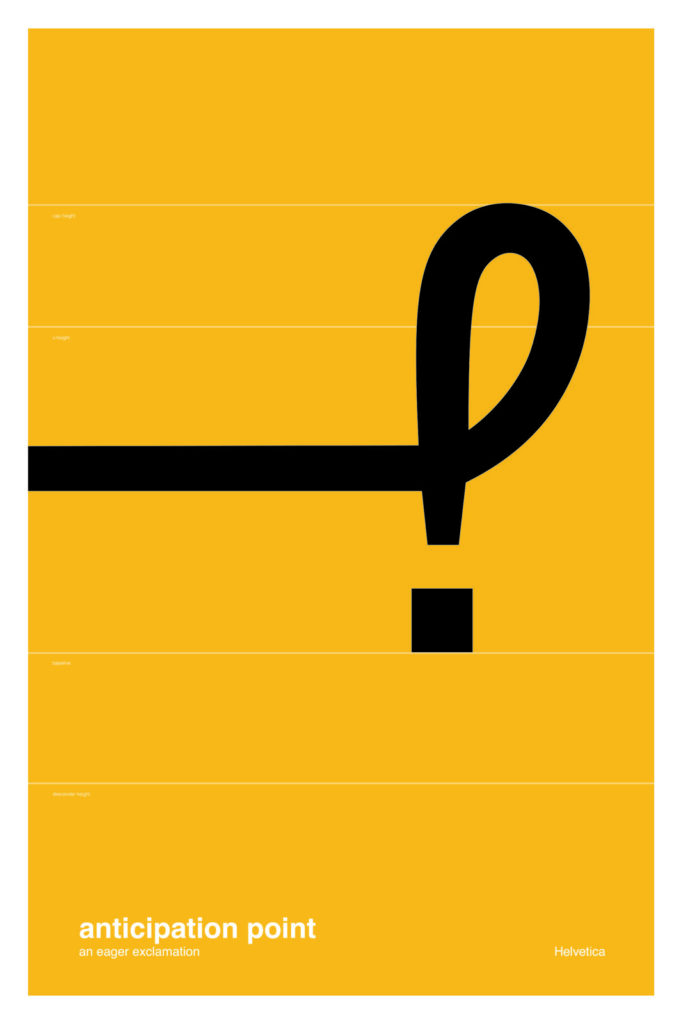

The series is concerned with clarity of expression and ability to convey emotion, but also with the future of ideas. It’s speaking both to language, and design itself, in terms of what the future of designed expression might look like. Cinelli genuinely enjoys this. She uses the term “visual inflection†to describe the performative nature of typefaces, fonts, and symbols, textual signifiers that communicate voice and emotion. Some of her Speculative Characters are indeed visual puns based on accepted punctuation marks, such as Awkward Pause (a horizontally elongated comma) and Anticipation Point (an exclamation point with a long, curvilinear lead-up), while others are clearly influenced by physical expressions, such as Angry Quotes (tilted quotation marks approximating a furrowed brow) and Shrug Sign (a kind of warped W representing raised shoulders). She acknowledges that the physicality of these forms is especially significant to her personally, relating, “I love the way we’re dealing with language, the fact that we’ve brought corporeality into what is now a digital space because we all understand…we can have a pretty clear communication based solely on facial expressions and gesture, we can have this communication and it’s in-person, which is really different if we call, and even more different if we text…physicality and tactile experiences, for me, are just huge and really important.â€

The importance of physicality in Cinelli’s output is evident when her larger portfolio is explored. Her Penance series (2019), investigates the identity of apology through hand-starched and hand-sewn pennants. The custom typography is also hand-drawn, before being digitally refined. Cinelli revels in the handmade process as a performative act, tedious, laborious, which she describes as its own kind of apology. To her, process imbues output with its own kind of layered message, and in this series the challenges of producing the work reflect the challenges faced when working up to an apology, or in parsing out which individuals, groups, or institutions should issue or receive them. Like crafting a meaningful apology, Cinelli relates the labor of working with intention, “They were difficult to make and really tedious, and they took all of this time, and I had to hand-dye this because I didn’t have the right color…[But] I like the act of making the work as well as the work itself, and I like the play of them, they feel really playful but they also feel really sad, which I really enjoy in my work.â€

Cinelli likes to take the recognizable and subvert what we think we know, taking the familiar and undercutting expectations. She brings forth tongue-in-cheek observations that also hold authenticity, speaking a common language with a foreign tongue, sparking interest. The Penance pennants speak the language of universities and athletic clubs, generic identifiers for specific groups. Cinelli takes these signifiers and undercuts the tribalism inherent in their visual language, pointing to the universal truth that everyone needs to ask forgiveness for something at some point. If we can get better at acknowledging our mistakes and asking for forgiveness, then perhaps our mistakes will stop feeling so monumental. This all plays to Cinelli’s penchant for speculative projects that work toward the way she wants the world to function, which is tied to the longing she sees running throughout her creative endeavors.

That longing is starkly front and center in Cinelli’s Insatiable Spaces series (2018), which includes facsimiles of parade candy, popsicles, and breakfast cereal. Her website states: “Engaging with the archetypal form of a house as a metaphor for the familiar, I aim to explore the physical manifestations of yearning through emotionally functional objects—addressing, alleviating, or activating our longing. Here, nostalgia and homesickness are similar as insatiable desires. These tiny spaces are sardonic faux-confections—simultaneously delightful and disappointing.â€

Insatiable Spaces also puts the artist’s subversive streak in focus. At first glance, the miniature clay and wood sculptures are convincing confectionary stand-ins, especially when they’re wrapped in intricately approximated waxed paper or cellophane. Cinelli describes the experience of observing viewers’ reactions to the work, noting that people often walk past the pieces or up to them expecting genuine treats, then reinvestigate, and then confront their upset expectations. “I like that kind of recognizable weirdness to these, that you know what they are and you know what they aren’t. So by the time you see them it’s like, ‘I thought this was going to be something else’.â€

While she cites nostalgia as a strong element within Insatiable Spaces, Cinelli leans into something harder to pin down and ultimately more productive in the majority of her work. Nostalgia is an easy target, especially in the current sociopolitical climate. Cinelli sees that people are yearning for “the good old days,†even though those days really weren’t so good. For her, it’s not about recapturing a feeling, but about finding a way forward, stating, “You want to go back and you can’t. You picture this other time and it’s totally gone. So for me, I think the work is more about navigating that experience.†This form of confrontation and memorializing is about re-inhabiting physical and mental spaces in another way. Cinelli affirms:

I think I’ve always been interested in memory and fleeting experiences and things that are and then are not…and so for me a lot of it was manifested in the ideas of home or places that you can’t return to, which I always find really strange. Those seem to be really salient moments in my life, when I leave apartments and I give the key to someone else…so there is that level of physicality. You can’t place yourself there anymore, you can’t physically go somewhere anymore, and the past, I think, is the same way.

This focus on fleeting experiences ties back to Cinelli’s sense of awareness, of being in tune with what is outside of herself as well as what’s in. If artists are cultural producers, they are as much cultural synthesizers, pulling things out of the ether to filter through a lens of subjectivity, in an effort to open people up to further possibilities. Cinelli’s personal philosophy is succinctly stated on her website, “It’s more about experience and less about aesthetic.†Her work is forthcoming, embodying perspectives gained from lived experiences. She attests, “In living, you pick things up and you hang onto them and you find yourself just carrying things around, and sometimes you’re just like, ‘well, I’ve got to put some of this down,’ and sometimes you just make the art about it, and then you can put it down, and it’s done, and it’s outside of yourself again, and you’re okay with it.â€

This is how she feels about the houses from Insatiable Spaces. Cinelli is stepping back from work in a similar vein after producing that series, then reproducing the work for concurrent exhibitions, and reflecting on the two shows. She frames these pieces as artifacts of experience, what she describes as “emotionally functional objects,†catalysts for understanding and acceptance. One of the more poignant and performative works in Insatiable Spaces is a model of the artist’s grandmother’s home, cast in soap. The casting is washed away until it disappears, tying in the physicality so often present in Cinelli’s work. Ultimately, this piece is about knowing the moment when a thing is gone, knowing when a thing is no longer the thing that it was, understanding it, and accepting it. When a colleague points this out to Cinelli, she acknowledges that this is exactly what she’s trying to pin down in this reflexive work, what she’s working through. Moving through life, picking things up and putting them down, and hoping it does some good for other people. When she discusses putting herself into the work, Cinelli confesses, “I care a lot about what I do, I don’t think I could do this work if I were half-assing it, because I want it to be good and I want it to be earnest…you can try really hard to make something that feels like it matters to you, it’s really earnest, you really want it to be something that comes from a place of honesty and of a kind of labor of love that comes from making stuff.â€

The earnestness comes through in Cinelli’s work, imbued by the artist’s genuine intent. In the world of contemporary art, there seems to be no separating the work from its maker. The artist’s name is their brand, and who they are is tied to the reading of their work. Cinelli concedes that this is somewhat of a struggle for her personally, “A lot of this comes back to identity, and who you are, artist or designer…or typographer, or all or none or both, and so much of my practice has been trying to figure out what that footing is and who you are when you’re with other people, because sometimes it’s both and sometimes it’s neither, and then what does it mean to be more than one thing, because it’s not like I make the same work all time….†While she maintains conceptual linkage of her output through themes of longing and speculation, it’s true that the media and aesthetics shift from project to project. Cinelli acknowledges, “Sometimes I’m casting silicone, sometimes I’m sewing some weird objects, sometimes I’m printing weird type, and there’s consistency of idea, there’s consistency of intent, but there’s not always consistency of medium, which I think can be really hard because you can probably look at my work and go ‘what does this person do?’ which is different from ‘what do they make?’â€

For certain artists, each work must be the thing it is meant to be, meaning the message is inherently tied to the medium. This requires learning new processes and experimenting with new materials in ongoing trials of error. For Cinelli, these moments of labor are also points of great excitement: “All of it’s labor, all of it’s work, and you can’t devalue the work you do, but I think you can frame it in such a way for yourself where you have to remember that it’s a privilege to be able to design, it’s a privilege to make art. I feel really unbelievably fortunate that I get to teach for a living and make art for a living.â€

While the look and feel of her work may vary, critical attention to her practice reveals a deep connective thread between Cinelli’s diverse output, which is—ultimately—an investigation of what it is to be. This kind of ontological approach to art and design necessitates the medium carrying the message. What unifies Cinelli’s practice is an awareness of the ways things are, a desire to change what she can, and an understanding that fostering earnest relationships among artists, designers, clients, and audiences means that sometimes the work must be more about the experience than it is about the aesthetic.

Mia Cinelli is an artist, designer, and educator based in Lexington, Kentucky. For more information, please visit her website at www.miacinelli.com.