Black-and-white images of leafless trees in cold forests, masked figures in suburban neighborhoods standing next to ambivalent children, family portraits taken in the rubble of abandoned homes – these are the haunting scenes captured by photographer Ralph Eugene Meatyard. In Stages for Being, the University of Kentucky Art Museum has put together a series of photographs by Meatyard that best represent his unique vision. Meatyard’s work is comprised of images of children, families, abandoned homes, and stark landscapes through which he explores how the outer world works as a stage on which imagination and inner life act.

Ralph Eugene Meatyard was born in Normal, Illinois in May of 1925 and raised in the neighboring town of Bloomington. After serving in the navy in World War II, he entered college where he briefly studied dentistry before deciding to become an optician. Shortly after marrying, he and his wife moved to Lexington in 1950. Here he worked as an optician, raised a family, and spent the rest of his life.

It’s in Lexington that Meatyard became involved with the Lexington Camera Club; a group of Kentucky creatives and intellectuals active from 1954-1974. Meatyard also maintained friendships with photographers such as Van Deren Coke and Minor White, and writers such as Wendell Berry and Guy Davenport. These figures would have a lasting impact on Meatyard’s work.Â

Stages for Being is a broad survey of the photography of Ralph Meatyard. Working with many pieces that have never been on exhibit before, the curator has organized the works not by chronology, but by subject matter. The exhibit fills the entire second floor of the Museum, a space normally reserved for the permanent collection. There’s a brief introduction to the life and works of Meatyard, and from there the photographs are divided into five categories: Masks, Interiors, Dolls, Nature, and Exteriors. This grouping doesn’t show the evolution of Meatyard’s work so much as it demonstrates how he used space and subject matter to explore various themes. It also demonstrates Meatyard’s consistency.

Within a twenty-year period, Meatyard developed his style. He didn’t do this simply through print size and camera model, but through his use of light, shadow, and composition. A Meatyard photograph can be distinguished by intense shadow offset by bright whites, as well as their theatrical and surreal nature.Â

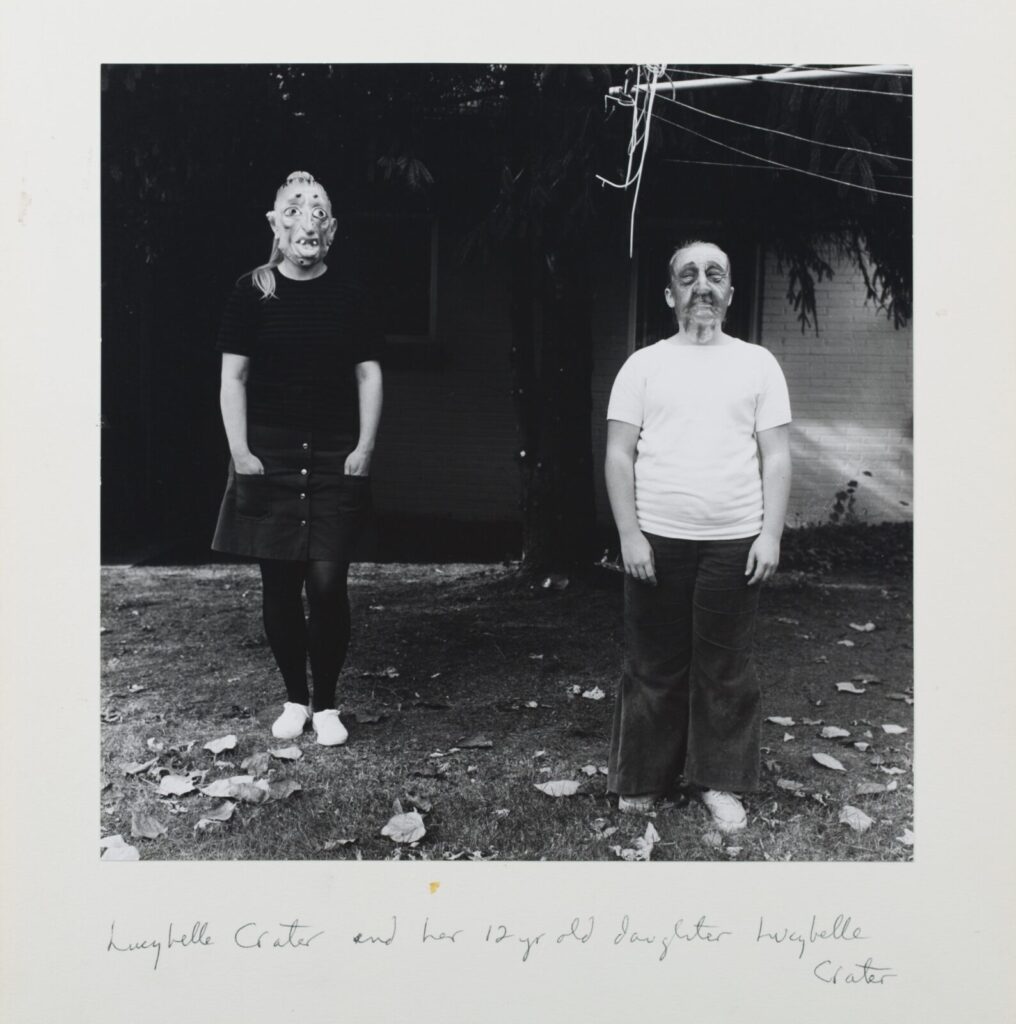

A discussion of Meatyard would be incomplete without looking at one of his Masked pieces. In these images, Meatyard would pose members of his family in various settings (often abandoned homes, or country landscapes) and have the subject(s) wear a mask. These masks were often grotesque, gargoyle-like versions of an old man or woman’s face. The masks are unnerving. The wearer’s identity is concealed, and the photograph is no longer a simple portrait or group photo. By donning the mask, the wearer becomes the mask. On some level the viwer is aware that there’s an identity behind this mask, but through Meatyard’s lens, the mask is the person.

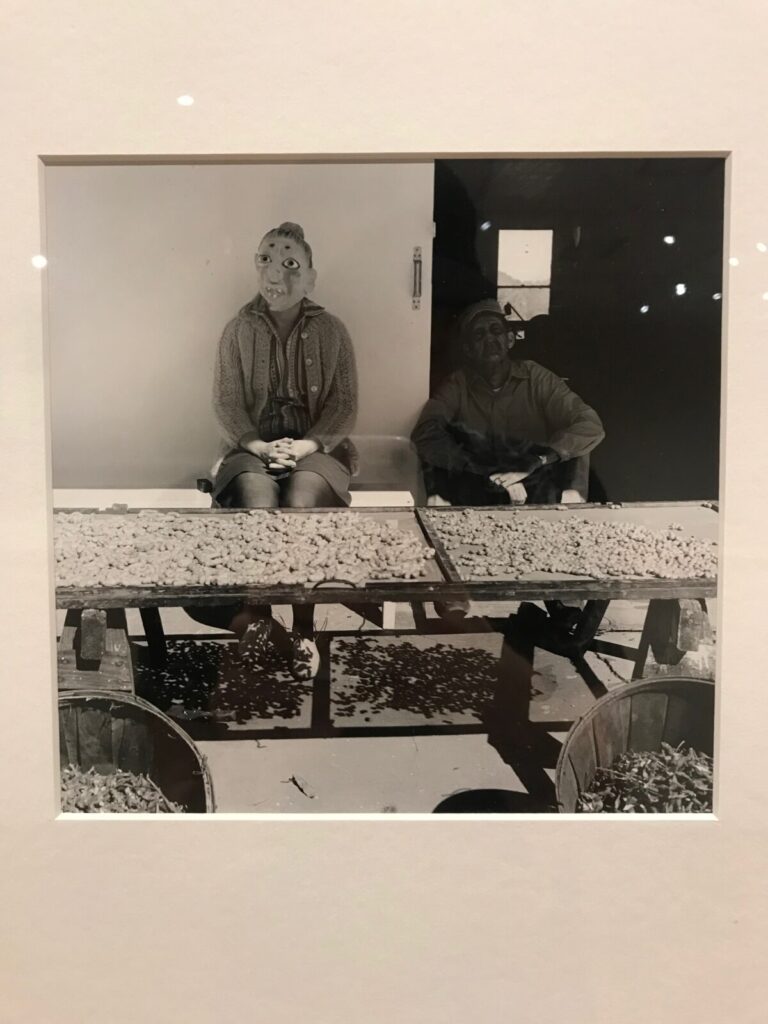

In Lucybelle Crater and Peanut Farmer Friend from Port Royal, Ky., Lucybelle Crater (1969-71), a man and woman sit outside of an open building with a large tray of peanuts placed before them. The woman Lucybelle Crater sits on a bench to the right of the man. Her arms are crossed and she’s wearing a skirt with a collared shirt and wool sweater. Her face is concealed behind the mask of a deformed old woman, a mask that can be found in many of Meatyard’s images. To her left sits the peanut farmer from Port Royal. He’s a whole head lower than Lucybelle, seemingly sitting on the floor. His face is hard to read, not because he’s wearing a mask, but because he’s wearing a ball cap and sitting in the shadow of the building. Lucybelle sits slightly forward of him, just enough that she’s clearly visible. The peanut table before the sitters is the brightest part in this scene, sitting directly in the sunlight.

Similar to other works in the exhibit, the table acts as a divider of the frame and distances the viewer from our two subjects. Meatyard often uses objects to divide and bisect his photos; a wall might separate two individuals, a tree branch might obstruct a landscape, windows act as barriers between viewer and subject.Â

This photo is part of a larger series: The Family Album of Lucybelle Crater. The photo is reminiscent of photographs in old family albums. Like pictures of people we’re related to but whose identity is lost. Using masks, Meatyard is commenting on issues of identity and image. On one level, the mask functions as a way to hide. Hidden one masks vulnerability. By masking one of the subjects, they take on a more relaxed, solid role in the scene. The masked person appears to truly be “a part†of the photograph. They ground the work. Their identity is firm and unchanging. An unmasked person must construct their identity without an aid. Unmasked, identity fluctuates. How does a photographer capture the mask as not just object, but idea?Â

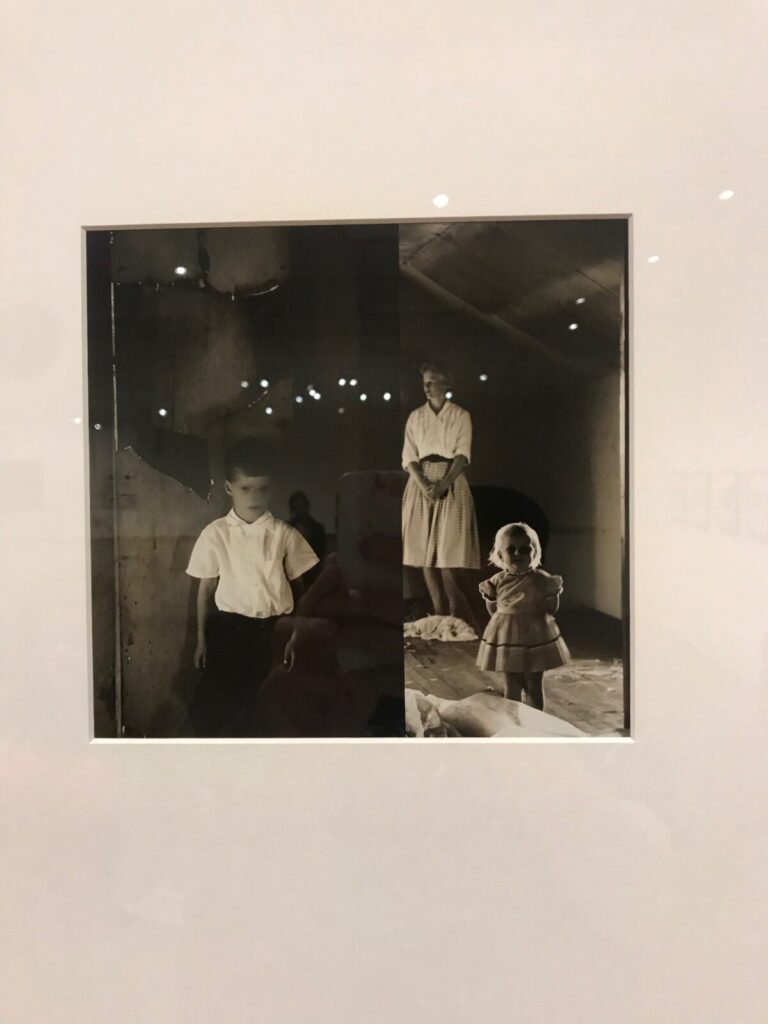

Issues of identity are also explored in interior photographs in similar ways. The interior of a home often conjures up feelings of warmth, family, and place. It’s in the home that we first construct our identity. In the family home, the identity of mother, father, and child are perhaps the most solid roles we ever have. Using his own family as subject, Meatyard explores the concept of “family.†In Untitled (circa 1967) a young Mother and her two children (a boy and a girl) are shown standing in an abandoned house. The boy is around five and the girl around three. They’re all dressed in clothing typical of the sixties; the mother wearing a long skirt with a white blouse, the boy wearing a white button-up with dark pants, and the youngest wearing a little girl’s dress. Each figure stands in isolation, without acknowledgement of each other. The mother stands in the very back of the frame, with her eyes and face looking away from her children. If not for her light clothes, she would disappear into the shadows of the room. The little girl stands in the middle ground, with her hands tucked behind her and her body completely fontal. She’s the only person in the image to acknowledge the camera. In the foreground, standing in front a door that separates him from the others is the little boy. He’s not even in the same room as his family. The door that separates him divides the frame evenly in two, further distancing us from the mother and daughter. The boy’s face is blurred, as if he was shaking his head at the moment the photo was taken. Meatyard hasn’t photographed a family, but three individuals united by the implication that a woman in a picture with two young children must be a family. In this scene, they are divorced from their roles, and stand as three independent persons.Â

This image offers multiple avenues of analysis. The separation of the boy from his mother and sister examines gender dynamics, while the distancing of the mother from her two children raises questions surrounding motherhood and independence. But what unites these interpretations is identity. Meatyard, like many of his contemporaries, had an interest in Zen Buddhism. Its minimal aesthetic and mindful approach to life, coupled with its teachings on self and identity clearly informed his practice. Zen Buddhism asks us to quietly observe the world around us, and in the process, revelations about our own self will become apparent. In this observing, we begin to discover the deeper part of ourselves that is beneath the role of mother or father or spouse or child. This is what Meatyard is getting at through his photos; an exploration of personhood that runs deeper than familial or societal roles.Â

On one of the panels at the exhibit, Meatyard’s work is compared to Ansel Adams. I was struck by the comparison that while Adams photographed nature as a subject that elicits in the viewer an emotional response, Meatyard photographed nature as a stage onto which our emotions act. This is what Stages for Being explores. In his photographs, we consider the different stages on which our being acts. Meatyard’s photography reminds us of the masks we wear, the parts we play, and the identities we take on.

Stages for Being is on view at the University of Kentucky Art Museum until December 9, 2018. This exhibition should not be missed. Admission is free, and the exhibit is a rare chance for the audience to get a quiet, intimate experience with works that haven’t been shown until this viewing.