I. Introduction

For almost two years now, our world has been flipped upside down and turned inside out with the coronavirus pandemic, including a new wave of record-breaking infections from its delta variant sibling. And we have yet to know how many offspring may be wafting in the breeze. Portentously, the entire globe is being inundated with one natural disaster after another, from droughts and wildfires, earthquakes and volcanic eruptions, to tropical storms and flooding, all compounding health crises and humanitarian disquietude in almost every corner of the world. Is there no respite? Perhaps there is if we allow ourselves to turn to nature and be “informed” by it, and understand that it governs by its own laws.

Luckily, for us, Informed by Nature is the subject of an awe-inspiring exhibition currently on view at the Headley-Whitney Museum on Old Frankfort Pike in Lexington, Kentucky. It features three au courant artists – Lexington abstract painter Helene Steene, painter and textile designer Alex Mason from Versailles, Kentucky, and photographer Jennifer Roberts from Lexington, Massachusetts – whose artwork addresses nature’s sovereignty through an interesting and diverse mixture of mediums.

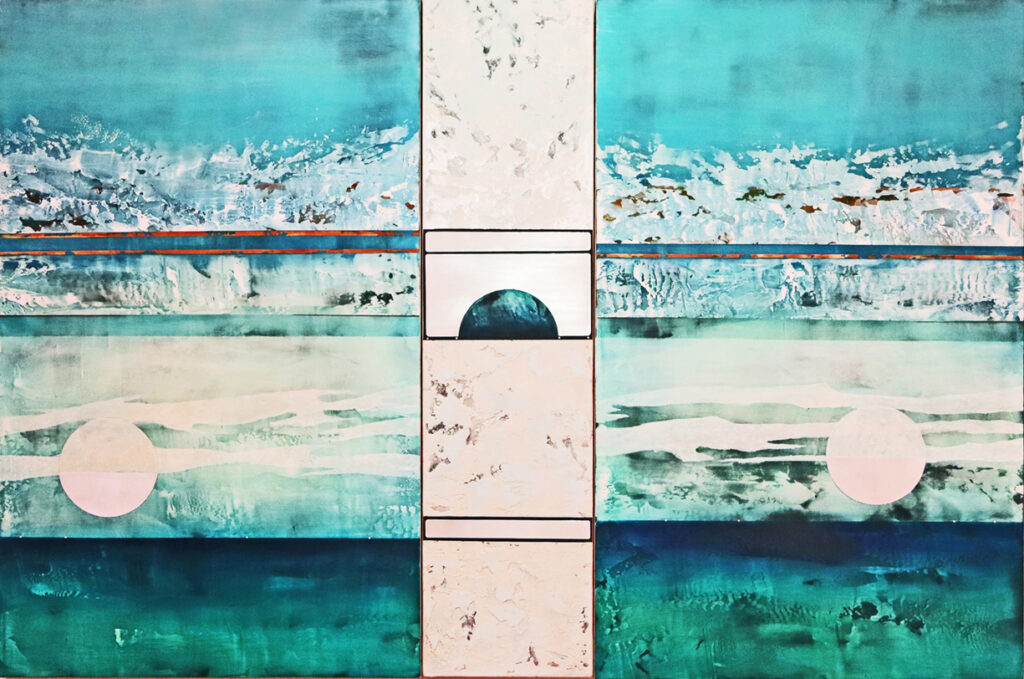

In Helene Steene’s Floating Moon I (three panels meant to be read as a single work), pale moons and paperwhite clouds sail beneath the horizon like weightless reflections rippling on the water’s surface tension. Above the horizon, briny waves rise and crash onto a golden shoreline and in the deep bluish and turquoise beds underneath the moons, specters of fish weave in and out of view. The ephemeral, disordered beauty depicted in the outer canvases of this triptych is anchored by the marbly unyielding center and its opaque stationary half-moon intimating a sense of stability in an environment where it is clear that the only constant is change – a law of nature that boggles the mind.

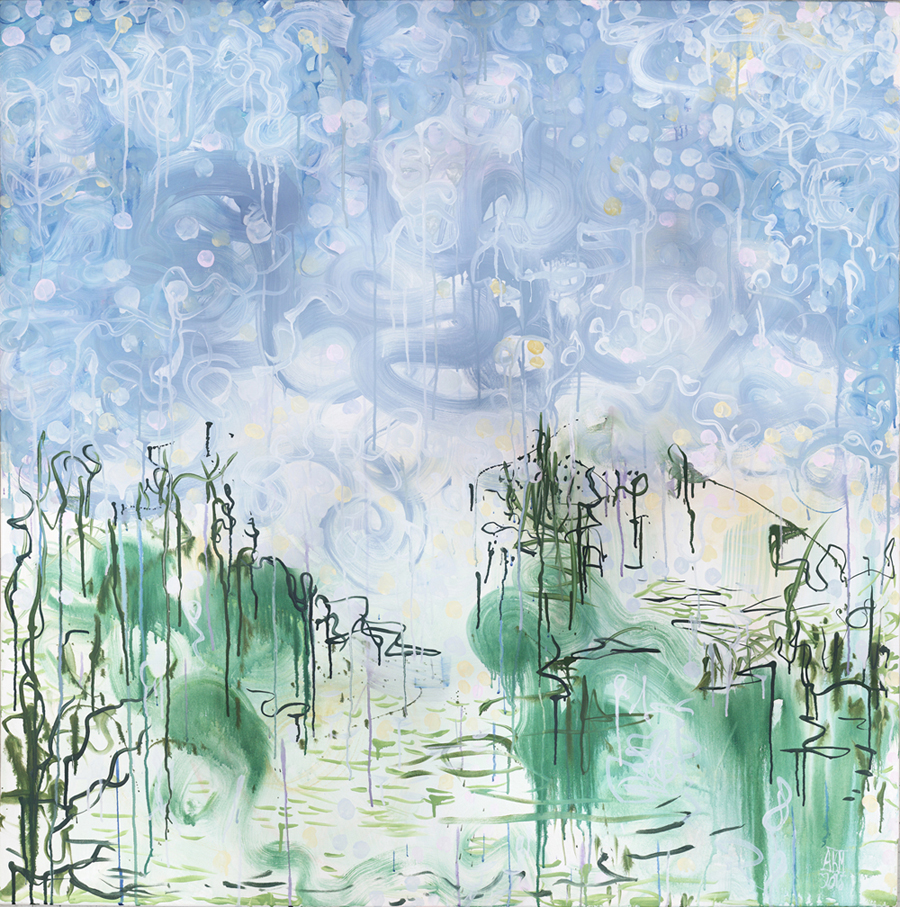

Alex Mason’s Gathering Storms in the Ancient Seas, inspired by Asian and Chinese art and calligraphy, is prescient and atmospheric in its Zen-like quality. Its power comes from suggestion rather than detail, and its energy from the splashes of color that drip, swirl, and shimmy all over the canvas. The nebulous sky of blues, whites, yellows, and tinges of pink churns. The twigs and reeds reel as the foliage bows from the weight of heaven’s gift that it shares with the pool of wavelets freely expressed by simple brushstrokes that bring this entire landscape to life. But the scene, as implied by its title, conveys an ambivalent tranquility that cannot be trusted. What can be trusted, however, is that nature will take its course with great indifference towards the life it sustains – an absolute for all living things.

Jennifer Roberts’ uncommon perspective of the common dandelion dazzles the eyes as it motionlessly spins light from the sun like a pinwheel catching a breeze. The shallow depth of field in both the foreground and the background brings into sharp focus a single spread of slender stems and feathery edges that permit each of these seeds to take flight and seek its fate. In the final stage of its life cycle, the “weed” in this image is transformed by light into a radiant sphere that will vanish just as quickly as it came into being. Not always obvious within one’s field of view, nature’s beauty often awaits capture by a discerning eye – precise moments of magical realism.

As you can see, the impact nature has on each of these artists’ mediums and subject matter is profound. And the allure of this exhibit comes from how they visualize and communicate this message to the viewer.

II. Helene Steene

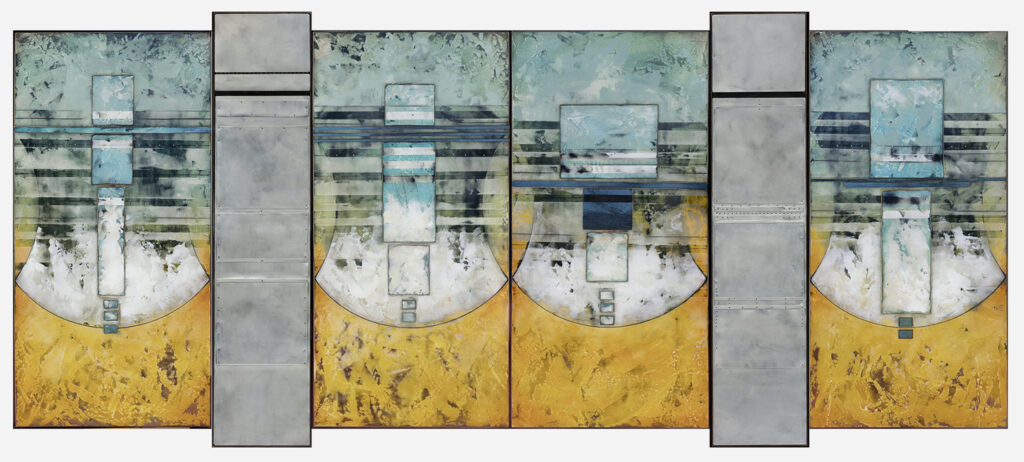

Helene Steene has lived and worked in Lexington for over thirty years, receiving her MFA from the University of Kentucky in 2004. Although she loves the Bluegrass, her relationship with nature gets recalibrated when she travels to her island summer home in Paros, Greece. This paradise provides her the time she needs to slow down, to contemplate her environment and her sense of place in it. It’s the same connection she wants her viewers to experience when they look at her art, a response she hopes will “add a moment of focus on their inner peace in this absurd world.” She mixes her colors directly on a prepared surface to create depth and permit her medium to take her where it will. This includes a coating of white marble dust from Paros which serves as a base beneath several layers of pigments that can be sanded back whenever she feels the need for more light to come through, giving her work its characteristic luminosity.

Steene’s Urban Eclipse is an engaging meditation of visually articulated ambiguities that begins with its title – the juxtaposition of two common words and the phenomenon we associate with each: urban, an adaptive environment created by humans, and eclipse, a naturally occurring event involving the earth, sun, and moon. The question is, how far can we go with human adaptation without eclipsing nature to the point that it will lash back? Given the increased frequency of cataclysmic events over the last few years, I believe we have our answer. Even so, via the vibrant colors and textures, the nuanced repetition of line and structure, and the dominating abstract forms that emerge from the planes that constitute the earth, sea, and sky in these canvases, the artist reminds us that a harmonious coexistence with nature is manifestly possible.

Ginkgo leaves, which inspired Silver Ginkgo II and other compositions, are one of many forms of nature that speak directly to Steene; and because of their distinctive shape, she states they deserved special attention: “I wanted to find my own language for them, so I did them in metal thinking here is a graceful and fragile little thing but I want to depict them in this strong contemporary material because the ginkgo is ancient, one of the oldest trees on the planet. Their use for medicinal purposes captured my interest too. I even titled one of those paintings The Ancient Healer.”

These aluminum leaves have a hypnotic effect on the viewer as they drift about the canvas in an aura of mystery engendered by the opulent hues of blues, greens, reds, yellows, and oranges. Silver Ginkgo II fully represents Steene’s medium and process of using multiple layers of glazed oils, marble dust, and strips of sanded metal on wood that contribute to the thought-provoking depth and intrigue exhibited by her paintings. Her goal, without exception, is to create work that “can slow someone down to contemplate something within her or himself . . . in the face of greater mysteries.”

III. Alex Mason

Alex Mason’s fierce independence and determination have afforded her to do what many artists only dream of: create her art and make a living at it. A native Lexingtonian, she received her MFA from Pratt Institute in 1998. Mason lived in four other states in addition to New Zealand and Australia before returning to Kentucky in 2015 to establish her business in Versailles and be closer to her family. Known internationally for her textile and wallpaper designs, Mason eschews the digital and delights in manually applying her paints, ink, and gouache to canvas and other surfaces. Everything begins first as a painting which in turn inspires her designs – free forms, shapes, and patterns that she extracts from nature as she stirs up a mix of iconographic symbols to “develop and simplify and use over and over like a spice in a recipe.” And the fact that Mason never has an exact idea of what she is creating until the work is finished only intensifies its savor.

Mason’s Something’s in the Air appeals to more than our sense of sight or smell with its abundant flora and familiar title. It stirs up a feeling we’ve all had, the perception that something is amiss – unseen but unquestionably present. Completed in 2020, this piece is the artist’s nod to the presence of COVID-19 without allowing the negative effects of the pandemic to dictate her choices for making art. She instead emphasizes iconic patterns and forms of nature that supply succor, that nourish the mind and body and heal the spirit. Among the rich greens, intense browns, and shades of blue and gray, it is not difficult to detect the symbolic shapes that vaguely resemble the molecular structure of the coronavirus itself. But it is not the sole “something” that’s in the air. There are other “spices” always brewing in Mason’s recipes.

Having grown up in Central Kentucky, Tobacco Blossoms are etched into Mason’s psyche as well as her canvas. The tobacco leaf even inspired a pattern she developed for one of her wallpaper designs, but she mused that its popularity was limited mostly to Kentucky and North Carolina. Imagine that. More important, Mason’s iconographic rendering of the former thoroughbred of cash crops is an aromatic dance which she says may have begun with a “doodle,” as much of her work does. If so, the doodle that gave birth to this painting went viral across her canvas in the most positive sense of the word. It is rife with kinetic energy – transparent lines, colors, shapes, and forms that border on elusiveness, that simply won’t stand still. While tobacco gets a bad rap these days and for good reason, Mason rekindles the beauty of its leaves and blossoms that was once commonplace in the Kentucky landscape.

IV. Jennifer Roberts

As an art historian and professor at Harvard University, Jennifer Roberts frequently thinks and talks about images of nature from an academic perspective. But when making her own photographs using a macro lens attached to her iPhone, the topic becomes a little more up close and personal. Because the lens must be held extremely close to the subject, not everything within the frame can be in clear focus. More than her technical skill, however, it is her awareness that “we are bathed in these wonders of natural illumination every day” and her ability to capture what “lies just below our normal range of vision” that create the transcendental magic her images exude. Roberts has come a long way from her high school days of photographing the landscape of northern California and working in a darkroom in the basement of her home. The photos for this exhibit were taken over the last year and a half on her daily walks through the meadows and wetlands near her home in Lexington, Massachusetts. And, for Roberts, these vignettes represent a state of being – small universes into which she is permitted only by “entering into their particular modes of natural stillness.”

The stillness of this untitled scene is both illusory and real because of Roberts’ “process of defamiliarization,” an intuitive “unknowing,” which leaves her open to exploring and discovering her subject matter on its own terms. She is not afraid of getting down and dirty with her photography. She says of her approach: “Because this equipment is so small and light, I can maneuver it into tight spaces and hold the lens at angles that would not be possible with a ‘real’ camera.” In this image, we are looking at sporophytes that have sprung from their mossy beds to gently frame the sun, to caress it and arrest its movement ever so briefly before its inevitable descent into the horizon. Roberts’ inventive use of the macro lens enables her to nail these magical moments because the “diffractions and other effects, which occur when light passes through and around the delicate edges of things, become much more prominent at this scale.”

Crouching on the shallow edge of this fresh-water pond, Roberts scrutinized the movement of the water, the reflection of light, and the shapes and textures directly in front of her: duckweed, curly-leaf pondweed, and fallen oak blossoms. Then her process began again as she leaned in closer to the debris holding her lens only inches away. She explains that “capturing an image with this focal structure feels less like standard seeing and more like feeling,” that it “resembles the sensory experience of touching something, running a finger along the surface.” Her comments reminded me of my contour drawing class where you could not raise your pencil from the paper nor take your eyes off the “thing” in front of you. You had to follow its contours and “feel” a direct connection with it. And so it goes with Roberts: “The macro lens is interesting to me not only because it magnifies objects but also because it magnifies my own sense of my tactile and physical relationship to the natural world.”

V. Conclusion

Going to a museum or art gallery a year ago was not only unthinkable, it was also not possible. Cities and towns boarded up their windows and rolled up the streets for the final six months of 2020 as the coronavirus surged and the number of deaths in the U.S. alone rose close to 400,000. We cloistered and quarantined, working, learning, and playing from our homes in virtual solitude, and we masked and sanitized our way into the public arena only when necessary. Outside, however, in the first few months of 2021, the less-traveled streets and roads were quieter, the air cleaner, the sky clearer, and rarely seen wildlife began to venture into our urban landscapes. Nevertheless, as we returned to some semblance of normalcy in our daily lives, the environment responded accordingly. Nature is powerful and sensitive to human activity, and it can feed our souls like nothing else except, perhaps, the art it inspires. But in order to maintain its equilibrium, nature requires that we take neither its beauty nor resilience for granted.

All three exhibiting artists share this wisdom – they have been informed. Roberts says, categorically: “My response to the spatial and emotional constriction of the pandemic has been to find solace in the expansiveness of tiny natural systems. At some point, when you zoom into the microscopic detail of a natural object, you cross a scale threshold where the world suddenly opens up and breathes again.” The droplets on this feather do an excellent job of magnifying Roberts’ message.

Unfortunately, she has only eight photos in the exhibit, untitled scenes without borders or frames – nature unrestricted and unrestrained. They leave you wanting to see more. Steene, on the other hand, has over 140 paintings and drawings in a remarkable retrospective that occupies more than two galleries, including a display of works on loan from various collectors dating back to her days in graduate school – all inspired by her undying love of nature and her beloved Paros. Here, without further comment, is her magnificent Red Eclipse – a universe for you to ponder.

Mason wanted to have fun with her installation and pay tribute to the museum’s founder, George Headley III, himself a Lexington icon. So she emulated his Shell Grotto by “papering” a wall, placing her cosmos paintings on the tray ceiling, and interspersing upholstered chairs (not for sitting) in the nooks between the panels containing her sketches of natural forms and symbols that, when applied repetitively, become the patterns for her textile and wallpaper designs.

Mason also spent 4-5 hours a day for several days painting a mural on the hallway walls to strengthen the sense of immersion as viewers enter and exit the gallery. Not afraid to borrow from herself when creating something new, you can see how her unique process works based on the painting hanging to the left (discussed earlier). The “mural” is new to Mason’s repertoire, her first ever, and the plan is for it to remain after the exhibit closes where it will continue to enchant visitors for the “foreseeable future,” honoring nature and the museum’s raison d’etre – the decorative arts.

After having been cooped up in our homes for what seemed like an eternity, Informed by Nature is indeed a breath of fresh air. And the museum, a gem of the Bluegrass, is situated among beautiful horse farms on Old Frankfort Pike where an excursion on this two-lane scenic byway is like a step back in time and a communion with nature. Both the exhibit and the drive will slow you down – in a good way – and lift you up.

The author extends special thanks to Christina Bell, the Executive Director and Curator of the museum for providing him with an advanced preview/overview of the exhibit. All images were provided by the artists unless otherwise noted.

Museum Location: 4435 Old Frankfort Pike – Lexington, KY

Exhibition Dates: September 10 – November 14, 2021

Museum Hours: Friday, Saturday, & Sunday 10 am – 4 pm

Museum Visits: For a COVID-free exhibition, the museum will follow social distancing, masking, and all health and safety protocols.

Website: Headley-Whitney.org

Email: hwmuseum@headley-whitney.org

Phone: 859-253-6653