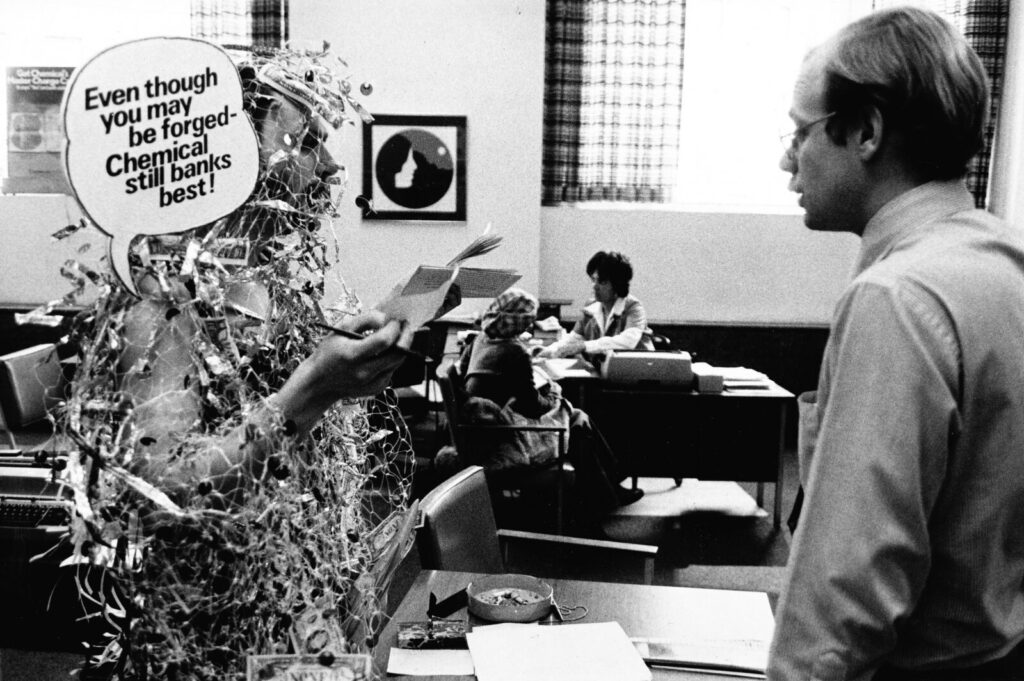

Stephen Varble is best known for his loud, disruptive, and public performances. During the 1970s and early 1980s, Varble staged several guerilla performances across New York City, all of which were notable for their garish, over-the-top displays of defiance and their provocative agitation, such as in his 1976 Chemical Bank Protest, wherein in protest of a fraudulent withdrawal from his bank account, Varble wearing “condoms filled with fake blood as breasts under a gown of fishing net adorned with sequins and fake dollar bills” handed a check for “none million dollars” to the tellers at his branch, signing the check in the fake blood that adorned his chest.

This performance, like many others of Varble’s, involved garish gestures and over-the-top costuming that challenged the construction of gender, the obscuring of (queer) sexuality, and the social fear of the bodily, issues that remained central to his art practice throughout his entire short life.

Yet while attention has been placed upon Varble’s public performances, these large scale displays were only part of his entire art practice. Now on view at Institue 193 in Lexington, the exhibition “Stephen Varble: An Antidote to Nature’s Ruin on this Heavenly Globe” — curated by David Getsy in conjunction with an exhibition at the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art — offers a more intimate view into Varble’s life and work. Comprised of 26 Xerox drawings, one etching, and his “epic and operatic video titled Journey to the Sun,” this exhibition offers a more static and subdued vantage into Varble’s practice, inviting the viewer to engage personally and individually in a way his performances never really could.

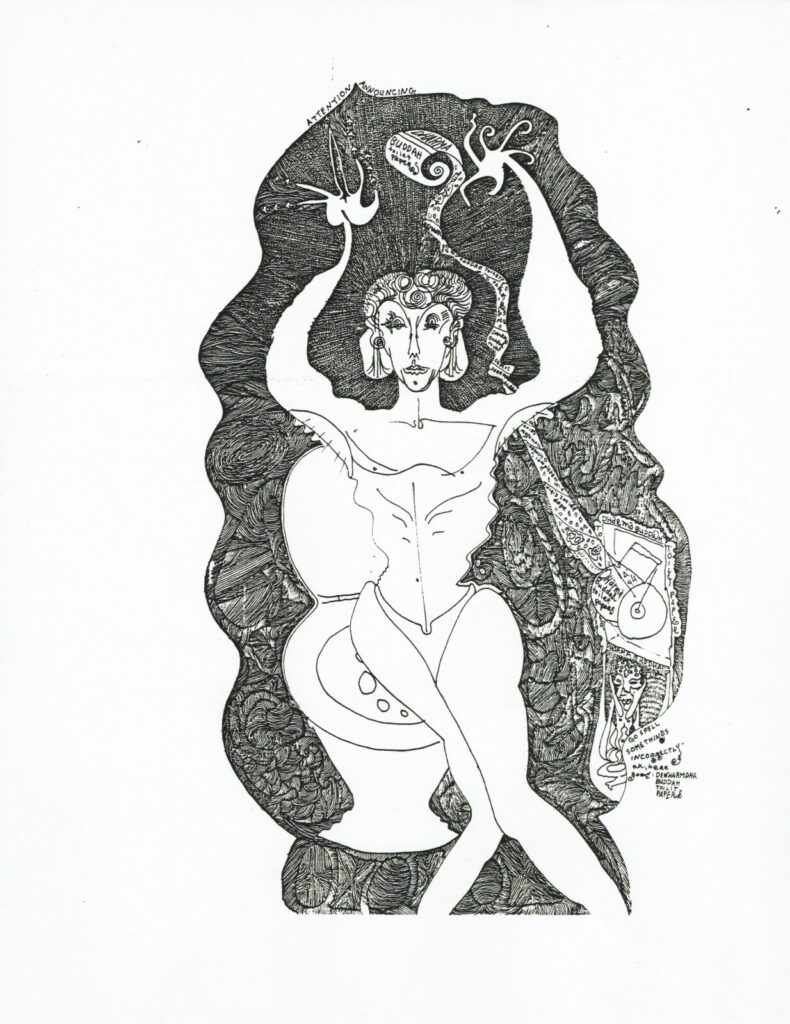

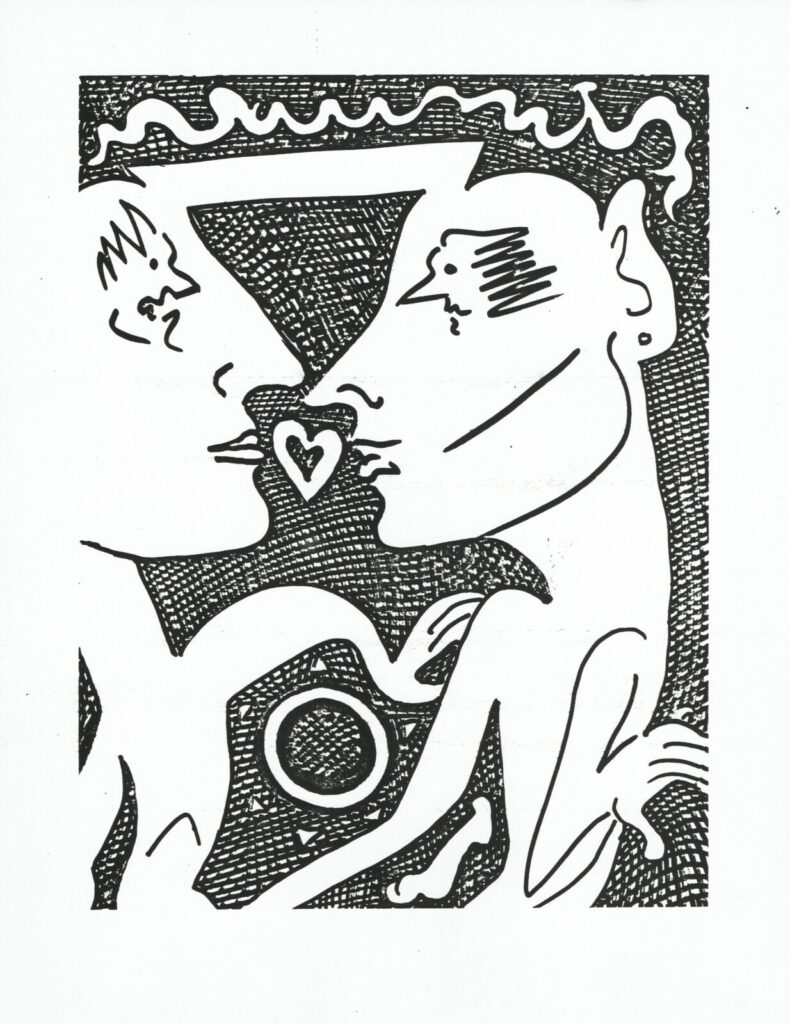

Varble’s drawings explore several of the same themes as his performance works, including issues of gender, sexuality, and the body, but they do so in a softer, more personal way. Like the gender non-conforming costumes he dons in his performances, Varble’s drawings — all of which focus on individual or groups of human figures — construct ambiguously gendered figures, highlighting a possibility of alternatives to the binary construction of man and woman. Several of his figures have feminine features — like defined breasts, hips, and legs — coupled with typically masculine broad and muscular shoulders, strong jaws, and facial hair. As such, these forms are neither exactly man nor woman, and thus call attention to the limits of such categorical distinctions.

Not only does Varble explore the issues of gender in his drawings, but he also examines the limits of the body in these works. The visceral processes of a living body emerge over and over in several of the works. In one drawing, Varble presents another ambiguously gendered figure sitting on a toilet, pulling a long line of toilet paper over their head. We can see solid forms floating freely in the bowl, as if the figure is in the process of or has just completed a bowel movement, although the white, circular forms look more like eggs than feces. The inclusion of the toilet is thus a reminder of the liminal nature of human bodies; on the one hand, we often walk around feeling like solid, impermeable entities, but several times a day, we viscerally spill over our physical boundaries and produce something external to ourselves. Like his depictions of gender, Varble’s inclusion of references to the process of excretion along with other visceral processes highlights how our conception of the body is defined by arbitrary distinctions, ones that are easily and readily crossed all the time.

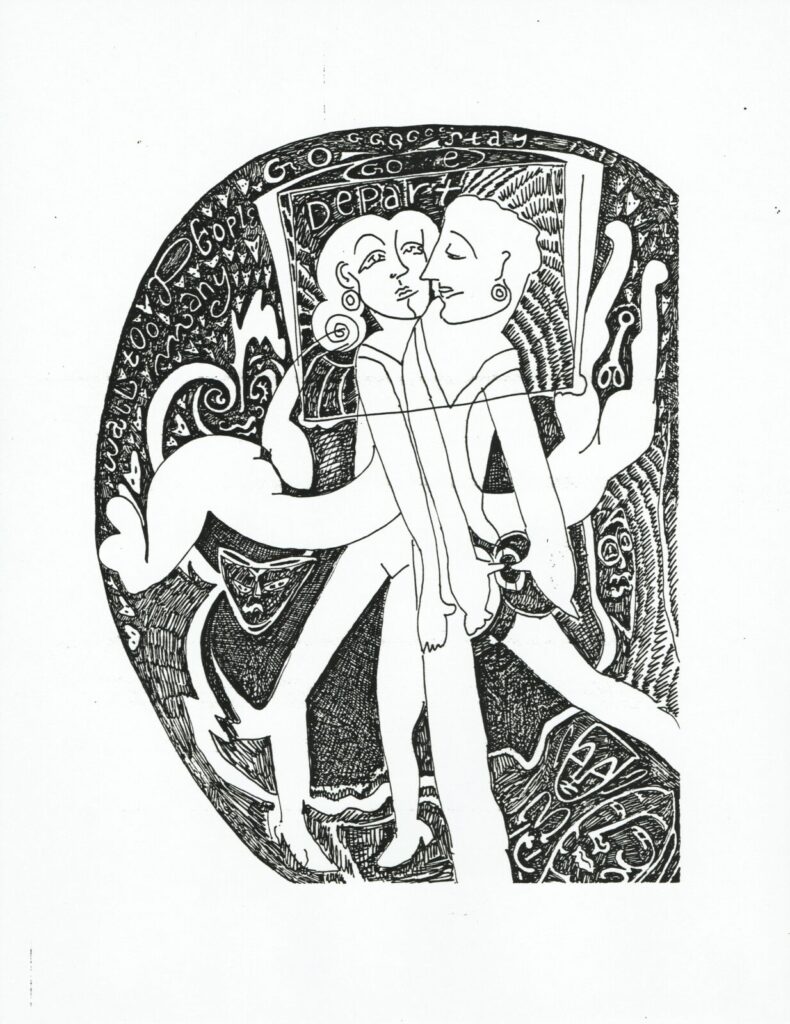

Varble’s work also examines the liminal nature of the body through his portrayals of sexuality in his drawings. Several of the pieces focus on pairs or groups of lovers engaged in various states of embrace. These displays of lust and affection highlight the limits of the body, as sexual expression often involves the convergence of two bodies within liminal spaces, lips, genitals, and orifices.

Moreover, Varble’s exploration of sexuality in these drawings is a further rumination on the relationship between gender and queer identity. For instance, in one work, Varble has constructed two simple and yet amorphous figures in profile, both with the strong jawlines and broad shoulders of men, although the ambiguities of the rest of their bodies make their gender impossible to discern. Their eyes have been replaced by the profile image of two other individuals, who gaze at each other. The two figures face each other, with their noses almost touching, lips pursed as if about to kiss. Between their mouths, Varble has made the outline of a heart and he has added a line connecting their brow ridges so that their noses form an upside down triangle, likely a reference to the Pink Triangle that was originally sewn on to the clothes of Nazi prisoners who were interned and executed for their homosexuality. Varble’s inclusion of the triangle is most likely a nod to queer liberation in his own time, since the symbol was reclaimed as a symbol of pride in the years following the Stonewall Uprising and especially in the early years of the A.I.D.S. crisis by the LGBTQIA community.

The symbolism of the downward pointing triangle is only further underscored by the band of pink that lines the gallery walls behind each of these works, offering a solemn reminder throughout the show of Varble’s life and death as a gay man in America in the 1980s. This pink line stands out against both the white of the walls and the black and white drawings, providing both a counterbalance to the curatorial convention of the white cube while also connecting the work to the longer history of LGBTQIA arts activism. As such, this simple band ties Varble’s work to the longer history of A.I.D.S. activist groups like Gran Fury and ACT UP and serves as a reminder that Varble, like so many queer men of his generation, was senselessly lost to what has become a manageable chronic disease. It should be noted that while medical advancements have made management of the virus possible, differential access to healthcare and resources both in the US and outside of it means that many people still live with and die from HIV and AIDS-related complications.

The somberness that this pale pink line brings to the exhibition is echoed in the color content of Varble’s works. Each drawing is rendered solely in black and white, providing them with a sense of seriousness and solemnity. Their subdued nature then provides the viewer the opportunity to engage quietly and contemplatively, an experience directly opposed to the over the top and vibrant displays of his performance practice, facilitating a more intimate view into Varble’s life and work.

Not only does the color palette create this intimacy, but the simplicity of their compositions makes them feel as if Varble is merely doodling these imagined images into creation, allowing a process akin to the Surrealist practice of “automatic drawing” to take over his hand. As such, these works feel personal and private, like they comprise the familiar world of Varble’s mind.

Moreover, the fact that these drawings were reproduced through Xerox copying and freely distributed further underscores their abilities to facilitate a personal connection to the work. Instead of being singular works seen only from a distance, Varble wanted them to be widely disseminated, allowing the viewer to engage with each work in their own time and in their own space; that Varble wanted these drawings to be held and owned by individuals offers the viewer — at least originally — the opportunity to have a more intimate relationship with his art objects.

The intimacy of these works is further underscored by the curation of the show. Arranged in a single line in the small single room gallery of Institute 193, the exhibition invites us to look closely at each individual work. There is no vantage point from which we can see the features of each work except for by slowly and meticulously walking along and beholding them one by one, requiring us, as viewers, to get “up close and personal.”

This sense of familiarity and closeness also resonates in how the show explores elements of Varble’s own history. While Varble is best known for performance works he created in New York City, he is, at heart, a Kentucky native. Born in Owensboro, Varble studied at the University of Kentucky and was a fixture of the Lexington queer community, returning often until his untimely death in January 1984. His performance work in New York was largely influenced by his time in Kentucky, and he even included close friends and relations from the area in his operatic video Journey to the Sun, which is also featured in this exhibition. In focusing on Varble’s Kentucky connection, the exhibition makes the work feel more relatable and at home to a Lexington audience. We know the streets he once walked and the culture he is drawing upon in his work, imbuing the work with a sense of familiarity and comfort.

On the whole, “Stephen Varble: An Antidote to Nature’s Ruin on this Heavenly Globe,” facilitates a personal engagement and intimate understanding of the life and work of Stephen Varble’s short life and prolific career. Both the works and the space they are in invite the viewer to look closely and consider each piece and the messages embedded within.