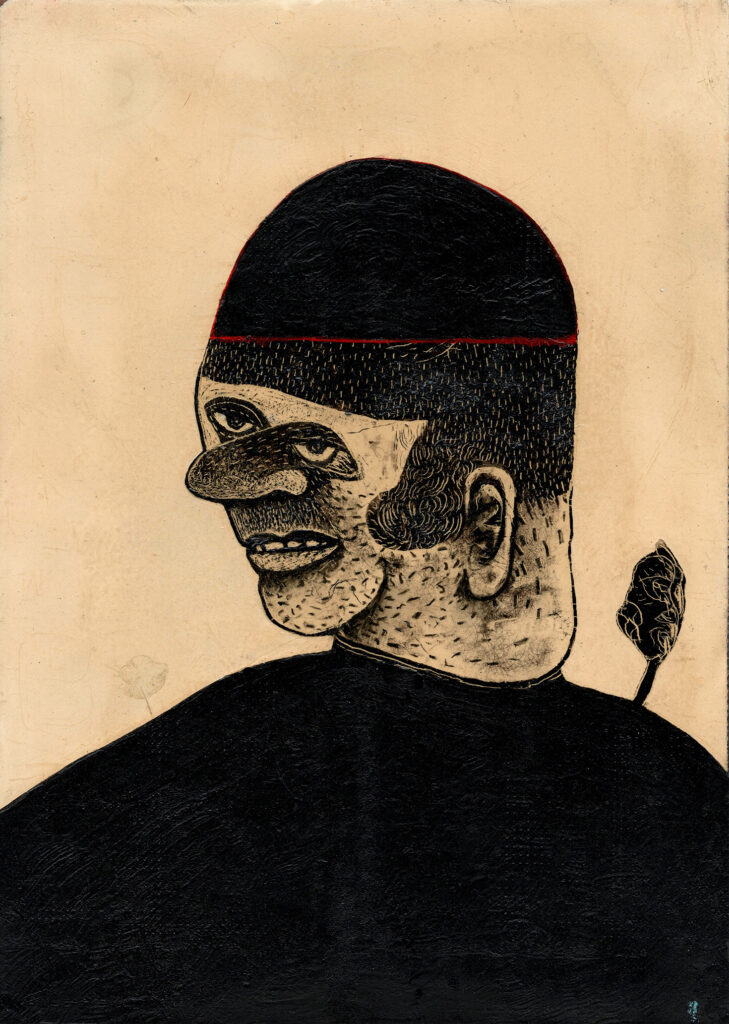

The world of Lexington artist Lawrence Tarpey’s paintings is at once dark and macabre, funny and playful. In a typical scene, crowds of strange figures, humanoid or animalistic or both, congregate and chatter; if you were standing among them, you feel, there would be a cacophony of crosstalk, jibberjabber and bleak jokes. They occupy murky landscapes that might serve very well as expressionist stage sets – for the witches in Macbeth, say, or the forlorn clowns of Waiting for Godot – under crepuscular, sepia-toned skies. Some of the creatures seem to grow up out of the ground, bulbous and solid as boulders, while others float overhead, translucent and ethereal like angels or ghosts. They seem to bicker a fair amount, but are more like large extended families than warring clans. Theirs is a shared DNA, monstrous, certainly, but no more monstrous than you or I, and sometimes a good deal less.

In “Lawrence Tarpey: Subconscious States,” the artist’s new solo exhibit at Institute 193 showing works from the past two years, these odd beings are the dramatis personae in various dramas that are constantly afoot. The show, which continues through March 6, includes “Back Seat Driver,” in which a hulking fellow with the paws of a wolf seems to be preventing the passage of a wheeled carriage chauffeured by some near-relative of Daffy Duck. In “A Much Better View,” a host of creatures on land and in the air appears to be eavesdropping on a heated argument, presumably over nothing very important, that has broken out between a trio of hotheads. In “Tic Tac Joe,” the conflict seems more serious, with a bear-like beast squaring off against a man brandishing a knife worthy of Crocodile Dundee. But the high stakes are undercut by another scene playing out at their feet, in which another animal with the face of a reptile serenely chomps a different man’s entire head in the manner of a cow chewing its cud.

Elsewhere the exhibit features at least three different apparent references to settings and elements associated with death, burial, and/or the afterlife. “The Excavators,” featuring a central figure holding a digging tool, is set in what might be an archaeological site or a graveyard. “Catacomb Central,” easily the most visually dark piece in the show, is a Dantesque vision of what could be an ancient underground crypt or, perhaps, a circle of the Inferno itself. On a lighter note, the denizens of “They All Worked Together” include what could be a floating mummy case and a wafting little fellow who could be Casper the Friendly Ghost’s helpful sidekick; if this is the underworld, life goes on here, nonetheless.

The alert reader will have spotted a plethora of “seem,” “could be” and “might be” references in the above paragraphs, a mark of how Tarpey’s richly ambiguous paintings refuse to be pinned down. Certainly most if not all specific readings of his work are mostly unintended, at least consciously, by the artist, until well into the process of creating each piece. And even then – despite his suggestive, sometimes cheeky titles, which he describes as “mostly afterthoughts,” conceived quickly and after the fact – he largely leaves interpretation to the viewer, and is fully prepared for the fact that many viewers may interpret the work as darker and more foreboding than he intends.

“I don’t think my art is congruent with my mindset,” Tarpey – a genial, barrel-chested man of 63 who retains the head of dark thick hair and the physical vigor of the punk-rock band frontman he also still is – says in an interview at Institute 193. “A lot of art critics have talked about the mysterious, dark nature of my work, but when I’m making it, I’m not thinking of it that way. I’m just doing what comes naturally to me. Sure, it has a darker palette. But more than a foreboding vibe, I’m almost more interested in conveying humor. Maybe it’s a combination of the two.”

In a tour of the show at the gallery and a subsequent, lengthy Zoom interview, during which we discussed his art, his artistic process and his life, Tarpey repeatedly emphasizes his art’s composition and other formal concerns over its thematic content. It emerges, he says, not from some intellectually pre-planned intention or creative vision but, rather, from his physical art-making process, which involves laying down blobs of dark oil paint and graphite, often with a sponge, on a pristine surface, usually clayboard or gessoed wood panel. He then works and reworks the paint – dabbing, mopping, scraping, scumbling, etching, sanding – until some evocative shapes emerge. At that point, and only then, he begins to develop and evolve those initially amorphous shapes into what have become his trademark human, semi-human, animal and hybrid figures, most of which eventually sprout limbs, heads, faces and, crucially, eyes and mouths.

It’s in that last step, of course, when the creative magic happens. The result is a weird and sometimes wacky dreamscape in which a vast cast of outlandish characters from the artist’s overpopulated subconscious romp, unfettered by reason, rules or anything else except the properties of paint and the typically tight confines of their frames.

But getting there is an intuitive process, not a cerebral one, into which Tarpey chooses not to inquire too closely.

“They just pour out of me,” he says of his frolicking figures and their shadowy stomping grounds. “I have no idea how it happens; I just know when it’s come together. Sometimes that happens right off the bat. Other times there’ll be maybe ten incarnations of a face. I work it and rework it until I go, hey, that’s pretty cool. And I leave that alone. And boom, there it is. There’s no explanation. And that’s what makes it exciting for me, frankly, because I have no idea what’s going to happen.”

Pressed, Tarpey likens his generative process to starting a fire in the woods. “You have to have wood, it has to be dry, and you have to understand friction,” he says. “It’s a process of putting all these elements together to create the fire, the fire being the painting.” Another analogy, he says, can be found in the once-popular childhood pastime of lying on your back looking up at the shape-shifting clouds: “Look, mom, an elephant!”

I suggest to Tarpey that this could be because he’s concerned that if he examined or interrogated the deepest origins of his art-making, it might disrupt his access to his subconscious, where all those little creatures live, waiting to be sprung.

“Exactly,” he says. “You’ve hit the nail on the head.”

*

Tarpey maintains a home studio in his small house in the west end of downtown Lexington, but he rarely paints there. That activity happens mostly in his living room, sitting comfortably on his sofa, almost always at night, often while watching TV, listening to podcasts or cranking up punk, rock and pop tunes, with occasional forays into the worlds of Frank Sinatra and Count Basie. (It’s a welcome respite from his other job, as a waiter. “When I’m waiting tables, I’m on my feet for eight hours. When I get home and want to work on a painting, I want to sit down,” he says with a laugh.) His favorite painting surface for more than twenty years has been clayboard. “It absorbs the oils, so your drying time is dramatically sped up, but not so sped up that everything sets prematurely,” he explains. “That gives you a nice little window of time where you can work the paint on the surface, scrape, etch, draw.”

In keeping with his free-associational, go-with-the-flow method of allowing his subject matter to materialize from the act of painting itself, Tarpey rarely makes studies. But once the imagery has bubbled up out of the paint, the artist dials in and begins to refine and sculpt the piece, often scratching and scumbling his surfaces with a utility razor of the type used in box-cutting tools. (“I’ve never cut myself,” he reports with a smile.) Generally monochromatic, most of the paintings feature foregrounds and backgrounds rendered in somber earth tones or shades of black and gray that recall the aquatints of Francisco Goya. “Subconscious States” does feature a few more colorful works, but these seem like the exceptions that prove the rule. The finished paintings are sealed in multiple coatings of varnish, giving them a pristine, polished quality that makes these hot-off-the-easel pieces feel like they might have been painted centuries ago.

The artist’s work sells well – he has several highly enthusiastic collectors who own many of his paintings – but that doesn’t seem high on his priority list. “I want people to like my work,” Tarpey says, “but it’s not for everybody, right? I’m not doing equestrian art, beautiful paintings of horses. I don’t have commercial concerns, really. It’s not part of the equation when I’m making art. I’m not thinking, how can I make this more marketable?”

He does make one commercial concession, in the area of size and scale. While he has occasionally painted large pieces, including murals, Tarpey is on balance a committed miniaturist, mostly for practical reasons.

“Large paintings are hard to sell,” he says matter-of-factly. “Sometimes people are intimidated by the size. Plus your material costs shoot up dramatically with large pieces, especially if you’re using good quality oil paint. And then, you know, it’s a matter of space. I live in an 1,100-square-foot house.” Accordingly, most of his paintings, including the ones in “Subconscious States,” are quite small, generally 5×7 inches (which currently sell for about $1,200), not including their bespoke frames, or 8×10 inches ($1,500). “The Excavators” was also included in notBIG(5), a 2019 group show at the M.S. Rezny Studio/Gallery that showcased works no bigger than 12×12 inches including the frame. Tarpey also creates limited editions of similar-sized digital prints, based on scanned bits and pieces of some of his paintings, that sell for $100 or less.

In a seemingly counterintuitive yet perhaps inevitable way, the constrained dimensions of Tarpey’s paintings might be a key factor in their being so heavily populated. In “Subconscious States,” for example, all but two of the works, “Gingus Kong” and “Profiles 2020,” are jam-packed with multiple figures and faces, as if in compensation for their small size.

“The scale is important – he has more ideas per square inch than any artist I know,” says Lexington artist Ron Isaacs, who owns 25 paintings by his friend (“the largest collection of Tarpeys in captivity,” he says) and is, like Tarpey, represented by the Momentum Gallery in Asheville. “There’s so much going on in his work, and so much of it is surprising. I like the wit, the pure invention, the general nuttiness of it. I don’t try to think too hard about what his little figures are doing or feeling, or what the mood is. Of course, I have a high tolerance for ambiguity, and I think he does, too.”

*

Tarpey’s career as a mostly self-taught artist began when he was 11 or 12, doodling on his beige laminate desktop at Lansdowne Elementary School in Lexington. “That Formica surface was perfect for a No. 2 pencil,” he recalls. “I would sit in the back of class and start drawing on my desk. The bell would ring, and then I’d come back the next day and the drawing would still be there, and I’d keep working on it. Of course, I wasn’t paying attention to whatever the hell was going on in class.”

Over the years, Tarpey kept on doodling – “Sitting in a bar with my buddies drinking beer,” he says, “I’d always be drawing on a napkin” – and the paint application process he uses for his mature work can be seen as a natural evolution of those early desktop drawings. But the journey from there to here was a long and circuitous one, slowed but also shaped by his ADD (attention deficit disorder), which kept him from excelling scholastically, and, he says, by growing up in Lexington in the ’60s and ’70s. “Being in Kentucky, it can be somewhat of a disadvantage, culturally,” he says. “You’re not getting much encouragement, really, and you don’t have the cultural resources that you have in a larger city.”

Tarpey did take a few studio art classes at the University of Kentucky, which he attended briefly, but otherwise relied on subscriptions to Art in America and other art magazines to inform himself about the world of contemporary art. “At one time I thought about applying to the Art Institute of Chicago or the Pratt Institute, but I kind of dropped the ball on that,” he recalls in a wistful tone. “Then I got involved in music when I was in my early 20s, so that took up a lot of my creative time, writing and performing in punk and rock bands.” As a lead singer and lyricist, Tarpey has been a key figure in several bands over the years with names like Active Ingredients, The Resurrected Bloated Floaters, Born Joey and Rabby Feeber, whose music he describes as “aggressive, testosterone-fueled stuff.” His two current outfits, The Yellow Belts and The CRISPRS, have been sidelined by the coronavirus pandemic but hope to begin performing live again later this year. “Here I am, 63 years old,” he says, “and I still love it.”

“One of the reasons I gravitated to punk rock was that it was a democratic expression,” he explains. “A lot of the early punk rock bands, they didn’t even know how to play their instruments – they couldn’t put two chords together. But I just like the DIY, anti-establishment spirit of it. Anybody could start a band.” His process of writing song lyrics, he says, in some ways mirrors and perhaps even influenced his visual art. “The genesis of a lot of my song lyrics is kind of stream-of-consciousness, but then I sit down and actually write, which is where the hard work comes in. A lot of my lyrics are not real literal. They have one foot in reality and one foot in the stratosphere, which makes them a little bit ambiguous.” Just like his paintings, he might have said.

Back to those art magazines. It was in those pages, Tarpey says, where he first encountered many of the artists who influence him to this day. They include Philip Guston, whose oddly stylized figures and jowly faces, often staring balefully out from abstract backgrounds, seem genetically linked to some of Tarpey’s (a good example being “Gingus Kong” at Institute 193). Even more foundational for the artist was the Chicago Imagists painter Jim Nutt, whose antic, often testosterone-fueled work melds surrealism, Pop art and underground comic-book art in a way that made Tarpey feel as if he’d found an artistic forefather.

“I immediately gravitated toward Jim Nutt’s work because it’s hilarious and pristine,” Tarpey says in words that, it strikes me, could be used to describe his own work. “He was one of the first artists that I was really intrigued with, and have been ever since. First of all, I like the bizarre imagery. I kind of gravitate toward psychedelic weirdness, and he checks all the boxes. Plus, the meticulous nature of the way he works. His images are just crazy, but at the same time exquisite; you can tell he spends hundreds of hours on one piece. There’s definitely a cartoony, underground kind of vibe going on in his work, which is another thing that attracted me to it. He’s not a traditionalist at all; he’s made his own path in the art world.”

Today, in addition to Nutt and Guston, Tarpey cites a host of artists as influences, including Hieronymus Bosch, Goya, Picasso, Rothko, Franz Klein, Cy Twombly, Milton Avery, Wayne Thiebaud, Kim Dorland, Matthew Monahan, and Nicole Eisenman. (“She’s in my top 10.”) It’s a telling list, spanning styles and centuries, with all but Rothko bridging and joining the figure with some aspect of abstraction or dreamlike imagery. “My work is always planted in the real world – there’s always recognizable imagery, although it’s mostly expressionistic,” Tarpey says. “At times I’ve tried to go into the world of nonrepresentational, purely abstract painting, but I always have gravitated back toward figuration.”

It was the artist’s combination of expressionism and his interest in the figure that caught the eye of Heike Pickett and her husband, Irwin. Heike is the veteran Central Kentucky art dealer who represented Tarpey for many years at her now-closed galleries in Lexington and Versailles. “We’ve always been drawn to his figurative work,” she says in a recent interview. “It’s a fascinating and very original process that he’s come up with all on his own – the way he doesn’t come up with an idea and then try to express it. He just starts painting, and then things somehow evolve out of that. Subconsciously, I think, he has all this in his head, but it can’t come out until he starts working. It’s extraordinary, like a high form of doodling.”

It’s been a series of short hops, then, from that Formica desktop at Lansdowne Elementary to those napkins in smoky Lexington bars to the pristine white clayboards on Lawrence Tarpey’s sofa. A high form of doodling, out of which comes a universe.

Top Image: Lawrence Tarpey, The Excavators, 2019, oil and graphite on claybord, 5 x 7 inches.

Images of art courtesy of Institute 193.