Care is a complicated word. On the most basic level, it means to keep something in mind and to attend to it. But the attention lavished on those things that we care for can range from the simple gesture of placing a precious object in a safe spot to the arduous and onerous labors of parenting and tending to the sick. Throughout her art practice, Diane Kahlo weaves together these two approaches to care. The objects she produces bear the marks of meticulous craftsmanship, highlighting the attention and labor she has put into each one, rendering them unique and precious. They are the result of careful work and are thus items deserving of care. The care that Kahlo imbues in each object is reflected in the care with which she treats her subject matter, specifically the lives and memories of those who have experienced gender-based violence and the exploitation of human beings and the lands they inhabit. Moreover, in attending so closely to these particular narratives, Kahlo implores us, her viewers, to consider and thus to care about those who are marginalized, victimized, and oppressed.

Care is something we do with precious and singular objects, items that cannot be easily replaced, and the objects that Diane Kahlo creates are marked by the care she takes in crafting them, rendering them worthy of preservation. Although she trained initially as a painter, Kahlo felt that she “[needed] even another visual language, sometimes painting wasn’t sufficient. I didn’t feel that painting could really address some of those things I wanted to address. So I felt that I needed to do a lot of exploration.†That exploration took the form of meticulously hand-crafted, “multi-level†paintings, in which she would “take a scroll saw and cut out these elaborately…kind of almost like a web work†consisting of cut out birds, vines and flowers, which she would overlay and integrate into her paintings, imbuing the works with a greater sense of delicateness.

One of the first works in which Kahlo began utilizing this kind of multilevel painting approach is her series Babes in Postcard Land. In this series, Kahlo appropriates the images of women from 1940s and 1950s vacation postcards – the kind that would feature wholesome white women in minimal clothing posing as an enticement for visitors – and places them in a hand-carved frame in the shape of a religious niche. The forms of the women and the various props that they hold, like long shafts of wheat in one or a pitchfork in another, are also carved, giving each piece a tangible, physical depth in contrast to the illusory ones that populate traditional painting. The multidimensionality that Kahlo ingrains in these works stands in stark contrast to the mass-produced flat postcard images from which the works originate. The handcrafted nature of Kahlo’s works makes each piece feel singular and precious, and the layering of each element gives the subject matter considerably more depth than the original ever could.

In adding new dimensions to these images, Kahlo is then able to challenge the relationship between gender and commercialization implied in the originals. She notes: “I really began to question these postcards that were enticements to vacation land, like come to Florida, come to California. Why were there always these sexualized ‘Girl Next Door’ images? Was it to entice the man to the land of fertility? Even that dichotomy between the girl next door as a sexualized image, the virgin/whore dichotomy.†In literally overlaying the land with the figure of a conventionally attractive white woman, Kahlo ties together two forms of objectification: the commodification of women’s bodies and the capitalist exploitation of the landscape and its natural resources. Presenting them this way demonstrates to her audience her care for these issues and, in turn, asks us to pay closer attention to the systems that inform our world that have become so ingrained that they become our form of kitsch.

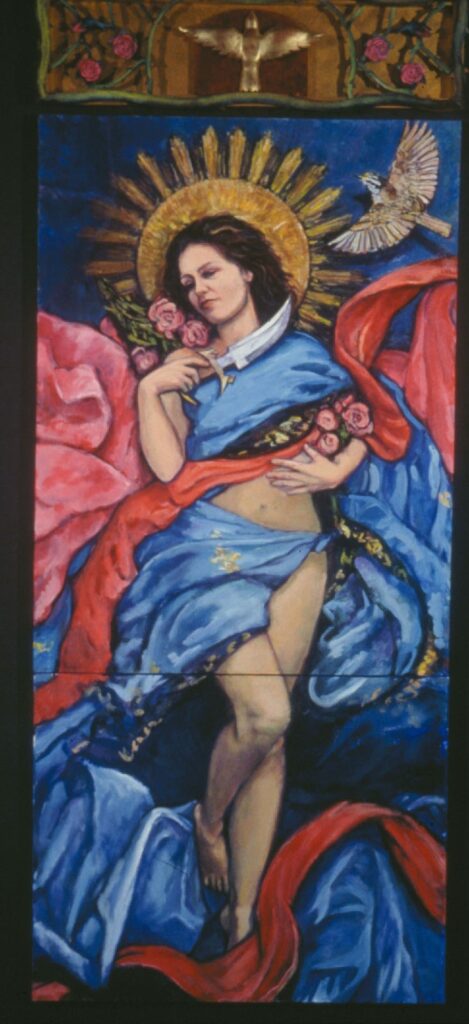

Kahlo has more explicitly used her work to incite care amongst her viewers with regard to the issues of gender-based violence. As in her series Babes in Postcard Land, in Myths and Revelations (2001) Kahlo combines the visible care of handcrafting with the emotional efforts of empathy to create several portraits of survivors of sexual violence. Kahlo depicts each woman carefully draped in the nude surrounded by a variety of natural and religious symbols; as Kahlo describes the process: “I had long conversations with each friend to learn about her hopes, dreams, fears, things that made her feel weak, symbols that she felt empowered by. I surrounded her in these objects and symbols, draped her in fabrics of her favorite colors, and photographed her so that she would appear to be floating. All these images became her ‘attributes’. I often carved some of these symbols to add to the framed portrait. About half of the dozen portraits had carved elements, and in the others, these symbols were represented in the painted object.”

The result is a series of large-scale triptych portraits that celebrate the power of the women depicted, highlighting their triumph over trauma and their ability to thrive in adversity. Kahlo equates their experience with the subjects of art historical masterpieces by integrating several highly traditional elements, like the contrapposto positioning of the legs, the classical billowing of the drapery, and several elements of religious iconography, ranging from blooming lilies – a common element of Renaissance Annunciation scenes – to elaborate gilded halos. Great care is taken in the selection of the images accompanying each woman and the rendering of the figure, objects, and drapery within the composition. Moreover, as in Babes in Postcard Land, Kahlo has added physical depth by incorporating both found objects and hand-carved elements, and in so doing reveals that the experience of trauma is, in fact, multidimensional, and a survivor’s narrative cannot and should not be flattened to focus only on victimhood.

The care that Kahlo offers those who have experienced sexual and gender-based violence extends beyond those she knows personally. In one of her most substantial works, Wall of Memories, Kahlo offers a similar kind of attenuation to the victims of the femicides of Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, a human rights tragedy wherein more than 350 women and girls have been targeted and murdered because of their gender since 1993. Stirred by the ongoing violence that has plagued this community, Kahlo worked for more than five years to create portraits of the various victims of this violence, 150 in total.

In conceptualizing the work, she wanted to build on other traditions of memorialization and thought particularly of the power of Maya Lin’s Vietnam Veterans Memorial, in which the names of those lost during that war are simply engraved upon a polished granite surface. “I had seen the very visceral response just to the name imprinted on the wall. People would walk up, they would touch it, they would make tracings of it, and it begged the question: ‘How do we respond to memory?’â€

Whereas the power in Lin’s Vietnam Veteran’s Memorial comes from reading the individual names of the approximately 58,000 American deaths in that war, Kahlo takes the gesture of individuation a step further in her Wall of Memories. In creating her portraits, she’s literally putting a face to the names, deriving them from photographs of the women who perished or creating them herself in the case of the unknown victims. As such, Kahlo makes real for her audience the pain and loss of a tragedy that is depersonalized because of the sheer number of victims. She noted in our virtual studio visit, “We hear names and unless you’re concerned with specific populations, they’re just names like Maria Jesus Rodriguez or something that doesn’t mean anything to people. I felt that if I put a face to it, and then I put numbers […] if I made enough so that I would create what I called a Wall of Memories.†In creating these portraits, Kahlo herself becomes the caretaker of the memories of these victims and, in imploring us to look, she asks us to share the weight of remembrance.

The work is challenging to view, and it was challenging for Kahlo to create. “I began and then it grew,†she says, “Then I became obsessed with my increasing pain, and even something beyond melancholy – a sinking feeling. And then people would ask why I continued, why I was doing what I was doing. Why are you looking at the faces of these little girls and imagining? And my answer was in the fact that the mothers couldn’t walk away.†For Kahlo the intense feeling of empathy – not only for the victims of this violence whose lives were cut short, but also for the families who only have memories left of their loved ones – meant that she had to keep working. She asserts: “I can’t walk away. I have to make it. So it at least does something – maybe brings attention.â€

The sense of overwhelm involved in both the creation and viewing of Wall of Memories has led Diane Kahlo to her more recent body of work, her series of Mandalas. For the last few years, Kahlo has been hand crafting mandalas – a geometric pattern derived from Buddhist cosmology – from discarded and cheaply made objects. The impetus to make the mandalas came from a desire to present something other than portraits following an interaction with a viewer. She notes: “I had shown it in one place where a woman walked in, and she was part of the Latinx community. And she held her heart and she needed a place to sit down and she said, “I can’t take it in. It hurts too much. I feel the spirits.” Kahlo decided that she wanted to offer her viewers “some areas of comfort†while also suffusing the installation of Wall of Memories with a sense of the sacred.

And yet, Kahlo’s Mandalas hardly shy away from the harsh reality of femicide or violence in general. These Mandalas consist of elaborate abstract patterns created out of everyday mass-produced objects and, like most assemblage work, function to pull us into our own lived experiences. Scattered among these found materials are clear references to the violence of the femicides, such as bullet casings or the plastic beads that young girls – like those whose lives were cut short – often play with. Moreover, that these materials are mass produced within factories by low wage workers is a clear reference to the victims of these femicides, workers in the assembly plants, or “maquiladoras” that had sprung up in Ciudad Juárez, particularly after the implementation of NAFTA (North American Free Trade Agreement) in 1994.

Not only does the mass production of the objects contained within each mandala allude to the individuals who produced them, but that facet of their creation makes them inherently disposable. That so many of the component parts of each Mandala could easily be understood as “trash†is central to the point Kahlo conveys with each work. She notes that “these objects had been discarded into the trash, ending up in landfills and polluting our water sources and I use them as a symbol for marginalized populations that are considered ‘disposable’. A great deal of my work has attempted to address the intersection of human rights violations and the human assault on our environment. I attempt to link environmental justice and social justice by using these disposed, discarded objects in a work that symbolizes life, death and rebirth [the mandala].”

By using these disposable materials in a work that ruminates on “disposable people,†Kahlo provides both with a kind of attention that undercuts their ability to be discarded. In placing the refuse from our daily lives – items we use, discard, and replace with such regularity that we never fully apprehend their forms beyond their function – into an elaborate undulating pattern on a monumental scale, Kahlo makes them part of something that is singular and precious, which bestows a similar preciousness on each component object. The care she takes in cleaning, arranging, and affixing each object in her Mandalas reflects the care that Kahlo took to create each portrait in the Wall of Memories.

Currently, Kahlo has been turning her attention to other circumstances of girls and young women whose lives have been cut short, often because they are treated carelessly and their lives are considered disposable. She recently completed a piece entitled “Jakelin’s Quince†in which she has created a memory box of found objects for Jakelin Caal. Seven-year-old Jakelin died in Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) custody in 2018 from a lack of medical care following an onset of severe illness, after being apprehended with her father. Accompanying the memory box, Kahlo painted a portrait of Jakelin as she might have looked if she had reached the age of 15, when she would have had her quinceañeara. In this piece, Kahlo considers what Jakelin herself would have cared about, including objects like rosary beads, dress fabric, flowers, and tiaras in her memory box, all items that refer to important instances in a girl’s life, like a First Communion or a quinceañeara. As such, she reinvigorates a narrative that has largely fallen away from our collective consciousness, and she also takes the time to attend to the memory of Jakelin Caal, separating her personhood and her lived experience from the conditions of her death, much in the same way Kahlo does for the victims of the Ciudad Juárez femicides.

Throughout her practice, Diane Kahlo ruminates on what it means to care. Whether in the form of the meticulous labor that she puts into her work, from her inclusion of hand-carved elements in her multilevel paintings to the careful collection and arrangement of found objects in her Mandalas, or with regard to the emotional labor she exerts in memorializing victims of systemic and systematic gender-based violence, Kahlo makes apparent that care is an active process. Moreover, the power of her caring is itself infectious; by creating works that draw a viewer in so deeply and that present multifaceted opportunities for connection, Kahlo implores us to empathize and to feel deeply for the subjects of her work, to lavish attention where we often would not and do not, and in so doing, begin to shift our perspectives and, hopefully, advocate for change.