As a tempestuous year comes to its close amidst bluster of impeachment trials and Brexit votes, threats to reproductive rights and struggles for minority rights, the ongoing opioid crisis and the progressing climate crisis, not to mention those stalwart nuisances of racism, classism and sexism, inside the sunlit halls of the Lexington Art League’s (LAL) Loudoun House home, all is calm, all is bright.

“Kentucky Nude,†this year’s iteration of the venerable organization’s once-annual-now-biennial nude show, runs December 6, 2019, to January 5, 2020, and features works by more than 50 Kentucky artists, juried by LAL studio artists Don Ament and Helene Steene. While previous years’ shows have been organized around tighter conceptual themes, such as self-portraiture or the rawness of human desire and physical form, “Kentucky Nude†presents more like a procession of classical figure studies, a mostly two-dimensional gathering of nubile white women reposing on sheets, sofas and other studio furnishings.

Not that there’s anything wrong with pursuing beauty for beauty’s sake. In fact, we should probably do a lot more of it, given the aforementioned political and cultural maelstrom that’s currently thrashing us about. To spend time with beauty and pleasure is, in some sense, to transcend the political, to affirm that there is more to life than the insidious crawl of the 24-hour news cycle, that we as human beings are far more complex and nuanced and expansive than any binary party system or policy debate would have us believe.

The difficulty is that the particular beauty on display in “Kentucky Nude†feels overwhelmingly overfamiliar, a sort of visual schmaltz on par with a dozen red roses, a batch of chocolate chip cookies, a kiss on the cheek from grandma. Perhaps more troubling is the show’s narrow range of flesh tones and dearth of minority perspectives – and of male physiques, much to this reviewer’s disappointment – which, while surely unintentional, comes across as slightly tone-deaf. Â

At least we still have laughter! “A birthday suit,†we call this too too floppy flesh, and some of the best works in the show take a more lighthearted look at a well-worn (so to speak) subject. Sarah Vaughn uses hot pink backlighting to frame her painting of a naked woman arching her back in a dramatic gesture of surrender rendered in melancholy blues. Titled Am I OK?, the red-orange spray-painted sad face looking down on the figure suggests that she is not.

On the neighboring wall, Megan Martin’s Abuttment Blue features ten joyfully colorful imprints where ten correspondingly colorful bums have abutted with her black canvas. It’s less like Yves Klein’s use of naked women as human paintbrushes, more like a happily erotic game of Twister, or the fine art equivalent of Xeroxing your butt as the office holiday party descends into debauchery.

Equally delightful is Aaron Lubrick’s Dan With His Cat and its playful nod to the afternoon luncheon: his companions in classical repose, formed in dark tones that quiet their nakedness; Dan’s cat a black silhouette that slinks in between the two; the landscape electric with acid-green grass, a periwinkle sea and a tiny red sailboat like a toy in the distance. Short, crude brushstrokes suggest an immediacy, a desire to capture this happiness lest it prove fleeting. (Milan Kundera, with a slight edit: “To sit with a cat on a hillside on a glorious afternoon is to be back in Eden, where doing nothing was not boring – it was peace.â€)

Not to be left out of the riffing-on-the-classics party, Todd Fife takes aim with Gabrielle d’Estrees Redux, replacing the two sixteenth-century French noblewomen with a corpulent pair of white-haired female friends, one delicately pinching the sagging nipple of the other as a ribboned speech bubble coaxes a quote from the Marquis de Sade from her puckered red lips: On n’est jamais aussi dangereux quand on n’a pas honte que quand on est devenu trop vieux pour rougir. (One is never as dangerous when one is not ashamed as when one has become too old to blush.) The mind reels in speculative delight trying to imagine the act lewd enough to elicit a blush from the salacious Marquis.Â

Sid Webb takes on the comedy-turned-horror-story that is the American presidency in the mixed media work The Word Only He Can Say Publicly, in which a starlet of the silent movie era gazes up helplessly as an orange-y, toupéed man in a black suit grabs at the word in question. It’s a scene that wouldn’t be out of place in the op-ed section, both because of its accuracy but also because it doesn’t seem to offer any new ideas to the current conversation. Curiously, the work is placed alongside two sculpted pieces – Maria Risner’s Melancholy Form and Rosemary Harney’s Pretty in Pearls – that, while respectfully depicted, nevertheless treat the naked female as mere object, leaving the viewer with the uneasy feeling that the sexist past is now more present than ever – or worse, that it’s become normalized.

Perhaps the more compelling response to the #metoo movement is Daja’s No. Her naked white subject walks away from us into a cerulean and sky blue color field, turning her head and shoulders to look at someone off to our right. Daja’s flat treatment of the figure creates a sense of affectlessness, as if distancing itself from the victim. The woman’s stare is equal parts pleading and withering – an emotional response that feels suitably discordant for a movement that empowered female victims at the same time it left a sense of despondence in its wake as we realized just how pervasive – and accepted – sexual violence had become.Â

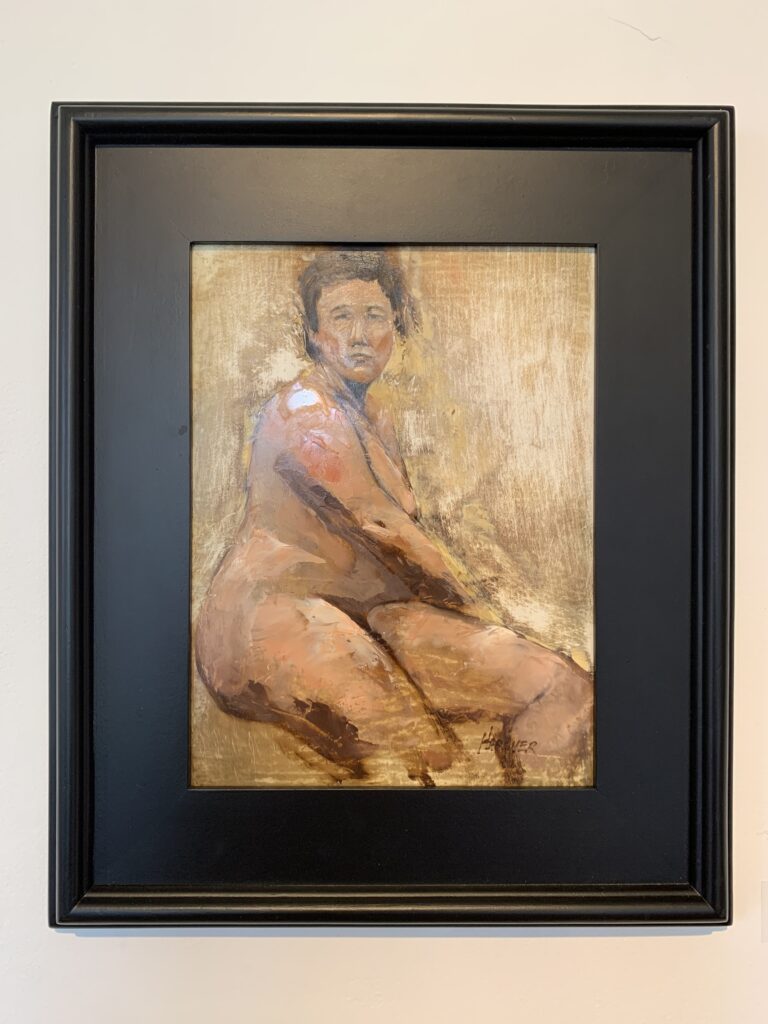

Still, the show offers moments of honesty and gentleness, such as the two oil paintings by David Harover, their smallness (each less than 12 inches square) inviting a quiet intimacy. Harover seems to reveal his figures more than paint them, as if his brushstrokes were simply sweeping away the soft brown and goldenrod pigments that had settled on top of them. His Alla Prima Nude #1 is an ample woman, modestly concealing herself with her arm as she turns her torso away from us, her expression one of detached contentment. Of all the works in the show, it perhaps most fully embodies the idea of nakedness, that raw and primal state in which we are stripped bare of armor and artifice. Harover’s subject is neither ugly nor erotic, only human – vulnerable, tender, adored. In a word, beautiful.Â