The space at the University of Kentucky Art Museum taken over by Mike Goodlett and Hunter Stamps for their show “Body Language†is all white light, white walls and ceiling, delivering microcosmic grandeur, with the floor holding most of the merchandise. The merch here are sculptures, some ceramic, some plastic and concrete, and they all seem to be humming different little mysterious tunes as you walk past them. The music is not music, though; it’s a new form of silence, manufactured by each little monument and doodad. A music that can hum itself into geometry and then into dream and back out into warehouse, reality, nowhere.

The humble materials seem to dictate that feeling of nowhere, but also give you something delightful to hold onto. In Stamps’ case, materials run the gamut from ceramic to rubber, glazed stoneware to encaustic. They are handsomely grotesque and grotesquely handsome totems dedicated to discovering what it means to be abandoned. Stamps creates a catalog of carapaces and nests and body parts no longer in use, monumentally devoid and yet somehow beautifully decorative because of the obsessive nature of their creation.

One piece, titled “Naked Lunch,†honors the icky, off-kilter 1991 movie David Cronenberg made based on William S. Burroughs’ icky messed-up novel, a terracotta paean to stylized verbal flourishes, but also baroque and stylish enough to pass as a vase. “Utterance†is a chunk of a Philip Guston painting come to life so it can die a miserable, beautiful death. Kind of like a giant, malformed ruby-slipper, the ceramic and rubber effigy accesses the tongue as its inspiration, but there’s a weariness to its positioning, like this big sad tongue just got back from war.

“Enrapture II,†a glazed ceramic riff on sci-fi horror tentacles freezing into stasis, is both a celebration of fierce otherworldliness and a quiet meditation on nature once removed. When you approach it, it seems to harden into itself from the other state it is in when you are not looking. That transformative feeling is built into a lot of Stamps’ works: they seem to be gorgeous props in some kind of big-budget nightmare, like John Carpenter’s 1982 magnum latex opus “The Thing” molecularly fusing with the detritus and emotions inside every 21st Century skull.

Mike Goodlett’s works play off Stamps’ theatrical body horror perfectly; they have a plush and sordid sarcasm built into their solid concrete souls, as if Hello Kitty and R. Crumb had babies. Playfully adorned in muted nursery hues, they are intense cartoons evaluating the atmosphere, controlling whatever environment they occupy with their passive-aggressive cuteness and de Chirico anonymity. The lovely and dour “Flower of My Secret,†made of plain old concrete and paint, hovers over itself with a cobra-like menace, and yet offers a sort of hardened comfort, a mummified sensuality. “Tiny Dancer,†made of hydrostone, paint and Mason stain, is a tombstone meshed with dessert, its sweetness overcome by its pallor, its finish basking in the unfinished qualities of its unnerving neck brace, its globular antennae. You feel talked to and ignored at the same time.

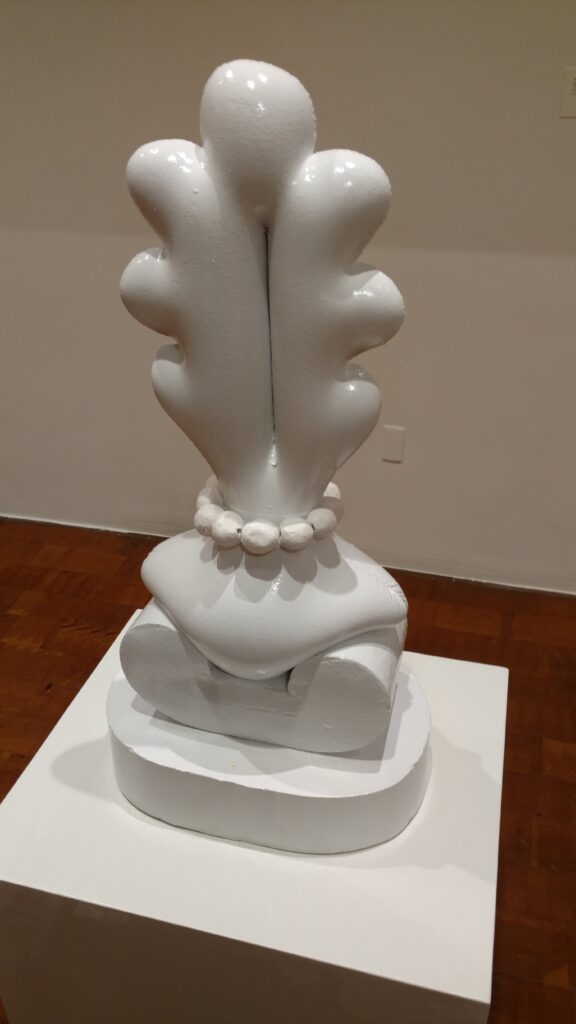

Another hydrostone and concrete masterpiece, “Sir Lancelot†references a dildo, an ashtray, and the supple shoulders of a 1920s mannequin, all in service to creating an object nothing can land on, meaning can’t find. It’s something meant to be worshipped, but also has a tough ironic sheen, a placidity earned from being warehoused within itself. It ain’t going anywhere, but it’s been all over the universe, glossy and crazy and very quiet.

Stamps and Goodlett have packaged their two-person gig under the title “Body Language,†pulling together two opposing forces in service to the absurdity of their pursuit: where does the body end and language begin? How can language ever really describe and/or contain the body with all its organs and tumors and bones, oh my?

The show itself could be likened to both a fulfillment center and a mausoleum, objects breathing and not breathing, curling toward their own version of glamour and also laughing at the way each one of them is dying an undignified death. Goodlett and Stamps have created a Vaudevillian planet together, an Aztec temple on acid, a nightmare toy shop, a landscape populated by creatures and things unnamable, and yet the body language emanating from each piece, ossified through concrete and clay, creates an ongoing and impenetrable narrative. Stories and histories come at you in a foreign language that has never been codified, never written down. All of these objects are refugees, survivors of some absurd holocaust only they know about.

And they aren’t talking.