Thoroughly Modern: Women in 20th Century Art and Design was conceived as a sequel to the Speed Art Museum’s blockbuster exhibition, Women in the Age of Impressionism. But this small, elegant display of women’s work stands on its own merits as one of the Speed’s best recent installations. The exhibition consists of only 35 objects or dinner ware sets but is mostly pottery. The show is on view until July 1st at the Speed in Louisville.

The artists are given momentous status with blown-up portraits of each on tall wall graphics placed between cases and wall works. As a display strategy, it works brilliantly.  Modestly scaled decorative arts gain in interest through the borrowed glory of their makers’ heroization. Â

The artists are by birth American, Austrian, British, French, German, Hungarian, and Russian, and their media include woodwork, paintings, prints, textile, silver and ceramics. This is a homegrown endeavor organized by the Speed’s curators, drawing on the strengths of the Speed’s own holdings, local collections, and the University of Louisville’s Hite Art Center. The artists range from Susie Cooper and Eva Zeisel, towering figures in the history of 20th century decorative arts, to a gifted amateur china painter, Althea Moore Smith. None of the women have been given proper recognition for the magnitude of their artistic achievements, and the fact that most are relatively unknown piques heightened interest. Â

Two vases by Anne-Marie Fontaine, (birth and death dates unknown), a designer for Sèvres porcelain in the 1920s and 1930s, are a case in point. To my knowledge, there has never been a museum exhibition in the United States dedicated to 20th century Sèvres. Fontaine’s supernal decoration of a three-part cylindrical vase is ethereal: overlapping gold and blue clouds rise in curved bands, interspersed with a sun, rain, feathers and stars. One can imagine Fontaine’s vase set off against rectilinear white walls in a LeCorbusier house of the period. The pot’s restrained elegance, cosmological whimsy, simple geometry, and integral relationship of its motifs to the vessel’s form mark it as an Art Deco masterpiece.

Not all the works in the exhibition are luxury goods. Eva Zeisel (1906-2011) designed for a mass market, working for manufacturers like Hall China in Ohio, Shenango Pottery in Pennsylvania, and Red Wing Pottery in Minnesota, and towards the end of her life, Crate and Barrel. Eva Zeisel’s 1955 Century platter and bowls anticipate Aero Saarinen’s TWA terminal: Their extended undulant curves made the set easy to stack for storage and easy to retrieve. Zeisel’s pottery is often characterized by a covert anthropomorphism: the handles of the Century dishes rise in hallelujah exultancy. In 2004 Zeisel wrote, “I have rarely designed objects that were meant to stand alone. My designs have family relationships. They are mother and child, siblings, or cousins. They may not have identical lines, but there is always a family relationship.â€Â

Zeisel’s biomorphic salt and pepper shakers for her 1946 Town and Country china precede by two years cartoonist Al Capp’s cartoon invention, “shmoos†which had comparable shapes. Zeisel’s implements intertwine and seem inseparably affectionate. Pertinently in a 1987 New Yorker interview, Zeisel asserted, “I think with my hands. I design things to be touched – not for a museum. A piece is ready when it has the shape of something to cherish.â€Â Wit is a continual factor in Zeisel’s art: the lid of the Town and Country teapot is off-center, giving it the comical air of a jaunty beret.

Zeisel worked in Germany in the late 1920s, and then traveled to Russia where she rose to the position of art director for the Soviet glass and china industries. Imprisoned for plotting against Stalin, she eventually was released and made her way to the United States. She was given a one-person show at the Museum of Modern Art in 1946, and is credited with designing the first all-white modernist dinnerware. She continued her protean creativity until shortly before her death at the age of 105 in 2011.

Susie Cooper, (1902-1995), is also profiled with wonderful examples. An English artist born in the Staffordshire town of Burslem, Cooper’s most characteristic product is the trio, a cup, saucer and cake plate suitable for Britain’s ritual breaks at elevenses or at afternoon tea. In contrast to Zeisel’s functionalism, the diction of ceramics in Cooper’s work seems more about convening, contemporaneity, and the contract of hospitality between host and guest. Her customers were the emerging British suburban middle class, who embraced 20th Century values of informality, enjoyment of color and innovative form. The patchwork enamel hues in Cooper’s earlier works are be-jazzed cousins of Sonia Delaunay’s Orphism.

A lusterware vase depicting a leaping antelope in front of an orange tree has a jubilant rhythmic composition characterized by unexpected intervals between figure and ground. The antelope was a favorite motif of Cooper’s, and was used in one of her pottery marks. Cooper could be more restrained in her designs. In a 1931 trio on view, the decoration shifts to delicate patterns of scrolls, circles, dots, and plant forms.Â

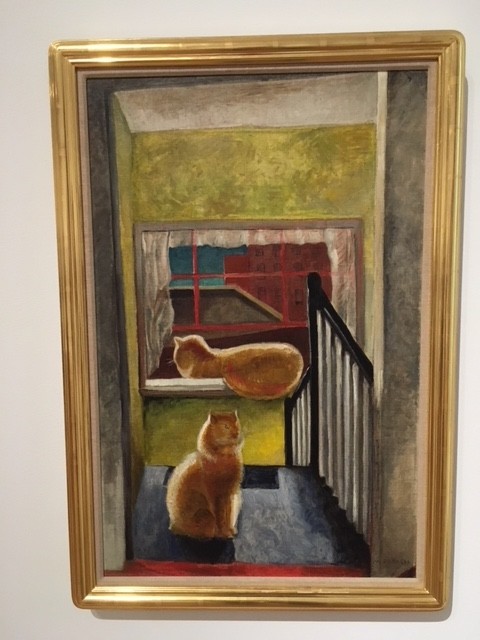

Of the paintings in the exhibition my favorite is the 1930 Two Cats on Stairs (Tooky, 10th Street by Marguerite Zorach, (1887-1968), whose reputation until recently has been overshadowed by that of her sculptor husband, William Zorach, the apostle of the ideology of direct carving. Marguerite Zorach was one of the first Americans to embrace the Fauve palette; a textile artist as well as a painter and printmaker, her painting in the exhibition is an exercise in Cezannesque pictorial tension, with its reverse perspective (the bannister recedes towards the viewer rather than into the distance, a red sill in the foreground is bound together with the wall of a brick building in the distance, the view of the roof through the window is angled up, the stairway tilted to the right). There are six interlocking rectangles in the painting giving the radiant backlit cats a supercharged stage set.

Morgantown, West Virginia native Blanche Lazzell (1878-1956), is represented by a painting and a print. Like Zorach, Lazzell domesticized European innovations: her 1917 loosely pointillist painting of Woodstock, New York, is constructed of large patches of overlapping complementary colors. It was done at Byrdcliffe, an arts and crafts school well-known for their costumed revels. Lazzell subsequently worked in Provincetown, Massachusetts – like Louisvillians Fayette Barnum, Maude Ainslie, and Mary Spencer Nay, who also worked there and found opportunities in the less sexist, more relaxed environment of summer art colonies. Lazzell’s 1946 woodcut, Abstract Petunias, is a cubist arrangement of spiraling flat planes of color: Lazzell was one of many Provincetown woodcut artists, like Cincinnatians Maud Hunt Squires, Ethel Mars and Edna Boies Hopkins, who used Japanese ‘white-line’ woodcut technique. Many of Hopkins’s most memorable prints depict Appalachians in Eastern Kentucky.Â

Thoroughly Modern succeeds because it is an exhibition of unfairly overlooked artists: it provides new visual information for all but specialists in 20th Century painting and decorative arts. It obliterates conventional distinctions between ornament and abstraction, undermines the primacy of painting and sculpture, and subverts the canonical hierarchy of male artists working in familiar styles. Most of all, it is an affirmation of the rich and still only partially discovered pathways of modernism.

Â