The central gallery of the the International Museum of the Horse, situated in the Kentucky Horse Park, is comprised of a single corridor that snakes its way along two floors depicting the historical relationships between horses and humans from the ancient Assyrian chariot horses and jousting steeds of medieval Europe, to the horses that helped move Conestoga wagons westward during the era of Manifest Destiny and the Thoroughbreds that draw millions to the races at Churchill Downs and Keeneland today.

At first glance, this equine inspired institution might not seem like a place to find a deep exploration of the history of slavery, Jim Crow, and systemic white supremacy in the American South, yet punctuating the middle of this sprawling timeline is a new permanent exhibition entitled “Black Horsemen of the Kentucky Turf†that complicates the narrative history on display.

This new installation, which opened April 20, 2018, makes a clear attempt to convey the overlooked contribution of black men and women, both enslaved and free, to the rich horse racing culture of Kentucky and the United States more broadly. Using person-centered language, including multiple narratives, and incorporating strong explanatory notes to help fully contextualize the experiences of the men and women who worked in all elements of this industry, the show addresses the horrific realities of slavery and segregation head on, analyzing the relationship of these practices to the development of horse and racing cultures in Kentucky. As such, the exhibition neither equivocates nor exculpates these institutions and demands viewers to consider the legacy of oppression with regard to contemporary equestrian practices. Â

One of the ways in which the exhibition faces down the hard history of slavery and segregation in the United States—and specifically in Kentucky horse racing culture—is the emphatic use of “person centered language†throughout the exhibition. More recent scholarship has involved a re-evaluation of the terminology we use to describe the practices of slavery; as Lucy Ferriss notes in a piece for the Chronicle of Higher Education: “There’s been a debate about the language of slavery—or slaving, as some writers prefer to call the institution—for several years. The changes that many have proposed […] put the emphasis on the humanity of people who were brought to this continent against their will and forced to work in bondage for generations.â€Â

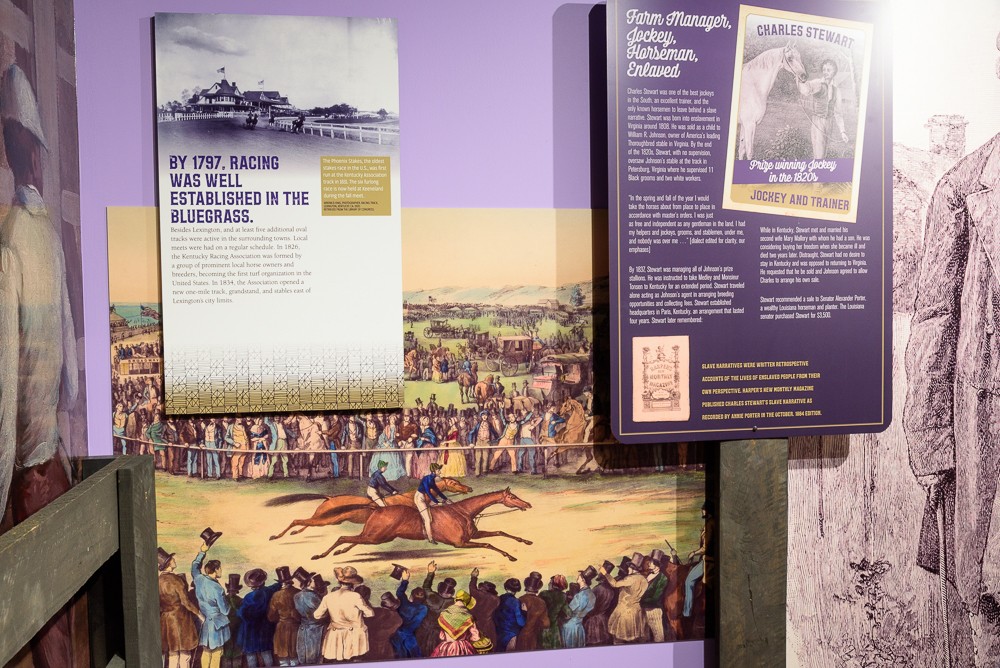

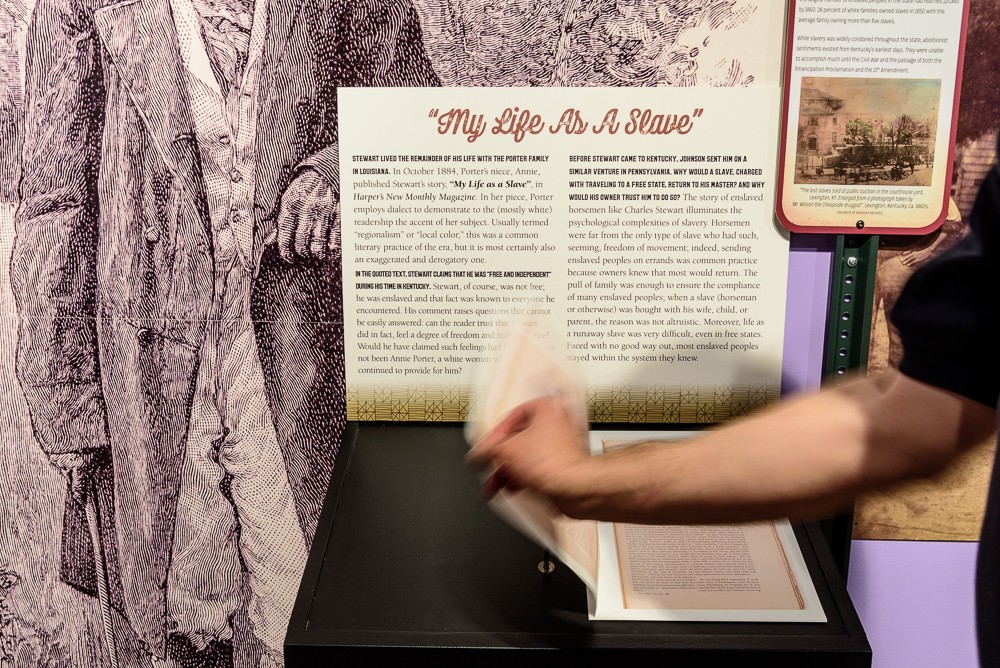

The curators have embraced this practice in their extensive didactic text, using the term “enslaved persons†instead of “slaves†and emphasizing fullness of the lives of each individual featured; the narrative texts, like those discussing Charles Stewart—who is described as “Farm Manager, Jockey, Horseman, Enslavedâ€â€”include the fact of enslavement, as opposed to solely focusing on that element of his lived experience, highlighting the whole human life that Stewart lived, for which slavery was only a single part. While such a gesture could run the risk of minimizing the drastic extent to which enslavement impacted Stewart’s life, the didactic text unabashedly acknowledges that Stewart’s role as a horseman was definitively linked to his experience of enslavement, and includes excerpts from his own biographical narrative from an 1884 edition of Harper’s magazine, a facsimile of which is reproduced below it. Â

Moreover, Stewart’s narrative is one of many that are included in this exhibition, providing multiple accounts of black men and women’s lived experiences in the Kentucky racing industry during the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries. The viewer is immediately presented with the variations of experience in the form of trading cards highlighting eight different figures—Ansel Williamson, Charles Stewart, Harry Lewis, Shelby Pike Barnes, Jimmy Winkfield, Isaac Burns Murphy, Marshall Lilly, and Edward Dudley Brown—that the audience is invited to take upon entering and is entreated to find the corresponding didactic text within the space of the installation.

In addition to these narratives, the exhibition highlights the experiences of several individuals who contributed significantly to black horse culture more generally, including Dudley Allen, who served as the Quartermaster Sargent in the “Colored Cavalry†of the Union Army during the Civil War, and Eliza Carpenter, a formerly enslaved woman who participated in the Oklahoma Land Run of 1893 and expanded the horse and racing industries out West. By presenting various experiences and perspectives, the exhibition avoids the pitfall of tokenism and expands the understanding of the variations that existed within the lives of black men and women living and working during the eras of enslavement and segregation.Â

Beyond simply presenting multiple personal narratives, the installation contrasts those stories with a considerable amount of historical explication in the form of signs marked “History 101†scattered throughout. These texts directly confront the complicated legacy of white supremacy both in the practice of slavery and the systematic dismantling thereof. For instance, the placard “About the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments to the US Constitution,†discusses the reluctance of Kentucky to ratify the 13th Amendment—which ended slavery nationally on December 18, 1865—until 1976, noting that “With the end of the Civil War, increased raids, beatings, and lynchings by vigilante groups made the Bluegrass countryside a dangerous place for the newly freed.†This text, therefore, challenges the common misapprehension that the transition from enslavement to freedom was smooth and beneficial for all, and that Kentucky, as a border state, was only passively invested in maintaining the practice of slavery.Â

The harsh reality of life for black men and women in enslavement and under Jim Crow is also documented through ephemeral objects and images around the exhibition. Photographs of enslaved people engaged in arduous labor appear alongside many of the tools they used. Images that show the clear dichotomy between the white spectators and the black horsemen who trained and rode the animals during segregation accompany journalistic accounts of the hardships and exploitation that these men faced in an effort to earn a living. Combined with the multiple narratives and the historical explication throughout the installation, these images offer a stark contrast to the celebratory history that exudes from the rest of the museum’s exhibitions.Â

Yet the curators have clearly gone through great effort to help the viewer experience this confrontation thoughtfully and introspectively. Within the exhibition space itself there are two points where the viewer is asked to reflect upon the information presented. At the “Conversation Station,†for example, the curators have posed the question “Based on the lives of Charles Stewart, Ansel Williamson, and Harry Lewis, do you think black horsemen were as highly revered as the horses they groomed and trained? Why or why not?†and provided the audience with post-it notes and pens to write their responses. The question itself incites the audience to deeply consider the ways in which the practices of slavery worked to dehumanize those in enslavement and how rhetorically and practically a slippage existed between enslaved persons and beasts of burden and the interactive nature of the activity allows the viewer to participate in the conversation that the exhibition is seeking to incite.Â

Moreover, being the only site in the museum to focus more on the history of humans than the history of horses and focusing solely on the experience of black people, this exhibition does run the risk of reinforcing the aforementioned conflation of African Americans and animals. Yet it is abundantly apparent that the curators were aware of such an historical linkage and thus have carefully provided physical room for reflection helps to unpack the problematic elements of that linkage. This effort, in turn, works to combat that particular issue.Â

The curators have gone through great lengths to confront the long history of racism in racing culture, providing the audience with a considerable amount of explanatory texts, ephemeral images and documents, and opportunities for reflection to help the audience process the thorough history presented in the space. This exhibition very clearly unearths the hidden history of black men and women within Kentucky horse culture and does so in a way that seeks to valorize their achievements and lived experiences while also confronting the challenges they faced and the legacy of white supremacy that we are still grappling with today. Â