The line between childhood and adulthood is muddy and complicated. When we are children, we are constantly looking forward, seeking to emulate the adults that surround us through our schoolwork, our daydreams, and our play. As adults, we frequently gaze backwards, thinking nostalgically of times when our lives were simpler and when we had not yet made the choices that would come to define our lived existences, where regret seemed impractical because the world was filled with endless opportunities. Moreover, childhood and adulthood are diametrically opposed, with childhood being defined by the inexperience of adulthood and adulthood being determined by maturity not found in childhood, all of which comprises the complicated processes of “growing up.â€

This push and pull between the conception of each life stage is at the core of the new exhibition OFF-SPRING: New Generations, now on view at 21C Museum Hotel in downtown Lexington. On the whole, the exhibition poses many complex questions about the limits of childhood, the definition of adulthood, and the processes that come to determine the passage between the two, presenting a multifaceted exploration of how the self is constructed through the internal passage of time we all experience.

One of the primary ways we transition from childhood to adulthood is through our education. Theoretically, the practice of attending school is designed to transform children into mature adults, capable of thinking deliberately and acting rationally on their own in the world. While this process could—and some might argue, should—entreat the development of individualism on behalf of the pupil, the result of this education is far more often a condition of universality, with students demonstrating similar knowledge and an understanding of the world at their point of culmination.

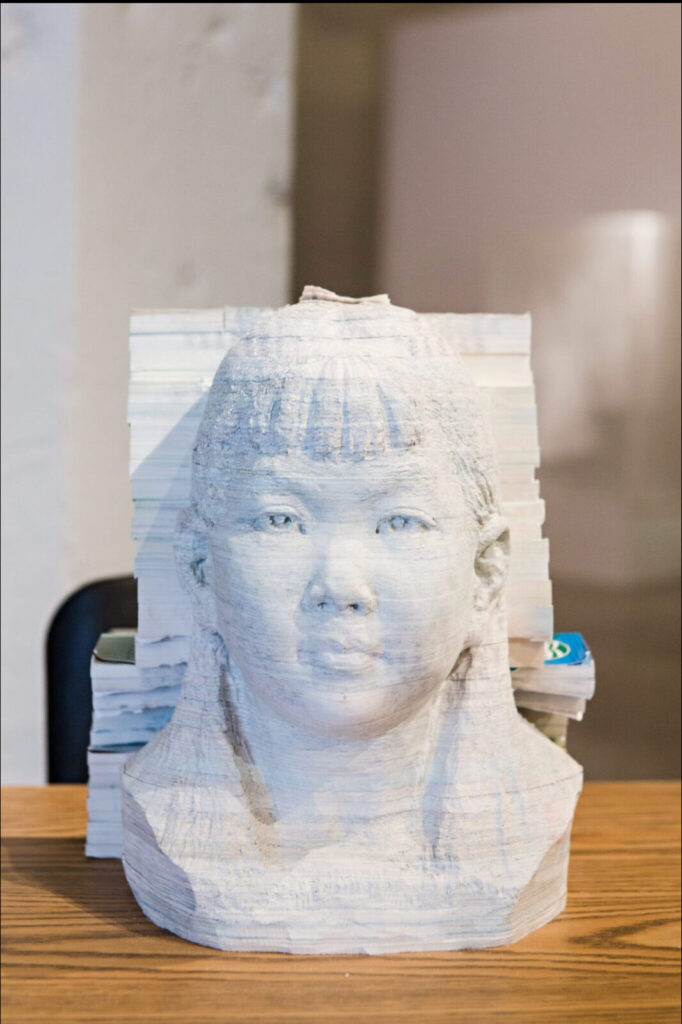

This uniformity through education is explicitly at the heart of Li Hongbo’s sculpture Absorption No. 5, which consists of a bust of a child, carved from Chinese government issued text books sitting on a school desk. The figure is therefore formed out of the same educational materials that every child receives in China, thus highlighting how on a fundamental level, all Chinese children are taught to be the same.

While Li Hongbo is skeptical of the sameness that is produced through education, Sofie Muller’s sculpture Clarysse highlights the attachment we feel towards education as a fundamental component of childhood. The work, which is the first one we encounter, consists of a patinated bronze sculpture of a young schoolgirl sitting at a wooden desk, but the head of the child has been removed, “leaving only an oval shadow burned into the desktop.†The removal of her face renders her anonymous, making her a synecdoche for any schoolgirl, and thus reminding the viewer of the uniformity of education across all children.

Yet, at the same time, the implicit violence of her decapitation, further underscored by the burnt shadow, entreats us to feel great empathy at the loss of opportunity for her, since it is a near universal belief that all children should have the right to an education and that the interruption thereof is a marked tragedy. Viewed so closely together, these two works offer a complicated consideration of how education works to transition children to adulthood, existing as a potentially positive opportunity for maturation while simultaneously being a system of formal indoctrination.

Although formal education is central to the maturation from childhood, informal development through play is also essential for children, and the enactment of that play is prominent throughout OFF-SPRING. In several cases, issues of play are used to illustrate how children seek to emulate adults in their own actions, often distorting the reality of adulthood in so doing.

For instance, Gerhard Demetz’s sculpture Keep My Own Dreams “depicts a frowning child, standing in a protective stance; he holds a baseball bat in one hand and a hairbrush out in front of the other, as if warding off danger.†The child is purposefully misusing these objects to help him emulate the bravery enacted by parents as they protect their children from unknown harms. This desire to replicate the parent on behalf of the child is further underscored by the fact that he is wearing the shoes of a grown adult, his small ankles pressed against the leather tongues revealing a substantial gap, an action that many children do as a part of their play.

Similarly, Carrie Mae Weems’ photographs Untitled (Mother, Daughter, and Make Up) from The Kitchen Table series and May Flowers unpack how play acts as a pretense of maturity. In both works, young black girls adorn themselves—with a crown of flowers in May Flowers and with make-up in Untitled—in a way that makes them appear more “womanly,†therefore practicing the grooming behaviors that will likely characterize their adult lives. By capturing the gestures of children’s play, both Demetz and Weems consider how these actions informally teach children the practices that will comprise their daily lives when they have fully matured.

In addition to considering the gestures of play, many of the works in OFF-SPRING also examine the objects thereof. Chris Roberts-Antieau, for example, explores the form of the doll house in her work Murder House. Employing the conventions of the dollhouse as a child’s toy—using appropriately sized figures and furnishings placed in a realistic setting—Roberts-Antieau subverts this kind of play by replicating one of the most shocking scenes of violence in the 20th century: the murders of the Clutter family in Holcomb, Kansas in 1959, a story that was memorialized in Truman Capote’s landmark work In Cold Blood. In depicting the murder scene in a doll house, Roberts-Antieau conveys a mature subject matter through an immature medium. In so doing, not only has Roberts-Antieau complicated the notion of a child’s toy through meticulously recreating the violent crime scene, but she also brings to light the ways in which the victims of this real-world horror, specifically the two teenaged Clutter children, were rendered mature by the violence they experienced.

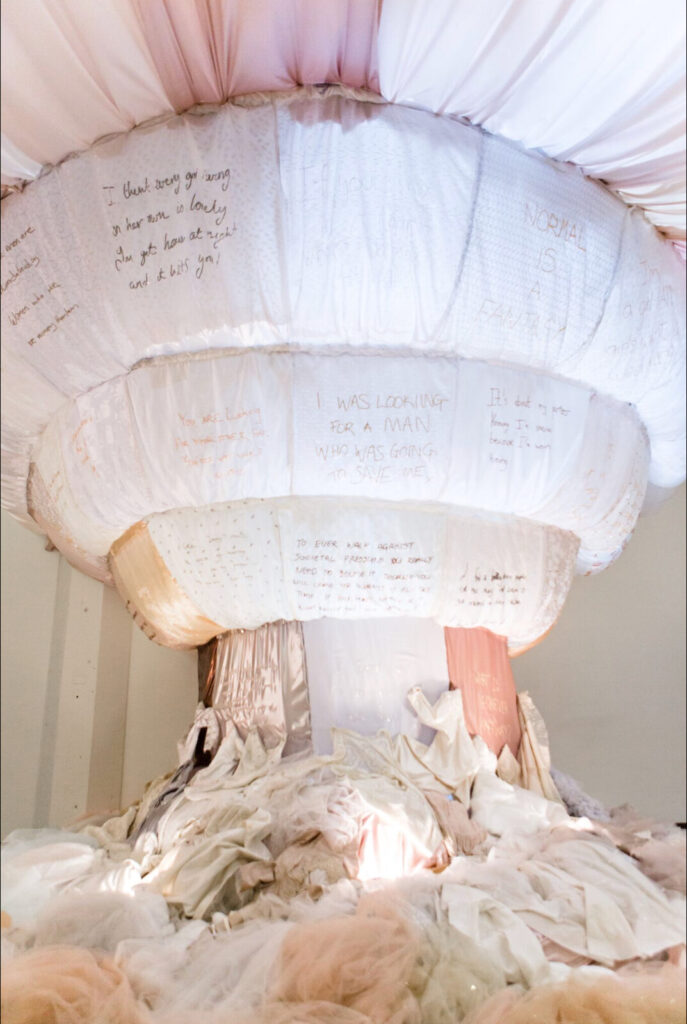

The intersection of playing at maturity and the lived experience thereof is also present in the way the show considers the ritual of marriage as a marker for the transition from childhood to adulthood, especially for women. In Frances Goodman’s installation The Dream, which “is comprised of satin, silk, and organza wedding dresses flowing from the ceiling to the floor in waves of pinks and whites,†the piling of the gowns, coupled with the soft organic nature of the sculptural form rising above them makes the space feel like a child’s playroom, with plenty of wedding gowns to play dress up in. This juvenile fantasy of marriage as something you can pretend to attain clashes starkly with the sound components of the piece and the quotes embroidered on the sculptural forms of the work, all of which derive from the “candid emotions of hope, envy, angst, uncertainty, and desire about the tradition of marriage†expressed by “dozens of women ages 20 to 60 †that Goodman interviewed for the project. As such, Goodman illustrates the transition to womanhood that is actually experienced by many when they move from bachelorette to bride to wife, a reality that is often far from the dreamed experience of young girls as they play.

While many of the works in OFF-SPRING focus on the differentiation between childhood and adulthood, still others consider the ways in which those relationships are intertwined, specifically within the context of the family unit. For instance, Daniel Magnusson’s serial portraits of fathers and daughters attending “Purity Balls†in Arizona examine the way that the practice of childrearing impacts the maturity of both the parent and child. In the photographs, the fathers hold their daughters close in an effort to support and protect them; while the idea of a “Purity Ball†might seem to be a sign of overbearing parenting, Magnusson notes that while he had a similar impression of the practice, “as [he] learned more, [he] understood that the fathers, like all parents simply wanted to protect the ones that they love—in the best way they know how.†The portraits thus function as an illustration of the maturation both of the daughters and of the fathers; while the Purity balls in many ways mark the transition from girlhood to young women, the participation of the fathers in them illustrates their complete acceptance of the role of parent as caretaker, recognizing that they are not only responsible for their own lives but the well-being of others, an act that by its very nature matures them.

Other works similarly tackle the issue of maturation through the depiction of inter-generational family relationships. Deanna Lawson’s Coulson Family, for example, explores the influence of familial legacies on the upbringing of her subjects, Black families that she meets “in grocery stores, on the subway, on road trips, during international travel, and on the busy streets of her Brooklyn neighborhood.†The images then take on the form of a family portrait, objects that by their very nature are meant to document the present for future generations. As such, these photographs not only illustrate how the family structure of today influences the upbringing, and therefore the identity, of a particular individual, but also calls to mind the complicated experiences of many previous generations. For Lawson, these photographs help to map the larger system of the experiences of black families living in the African diaspora and help personalize the experiences of various individuals within the context of a greater global black history.

Race and gender are two of the many themes that re-emerge throughout the show, further blurring the focus of OFF-SPRING: New Generations, and making it clear that this is not simply an exhibition about childhood and maturation. The show is, in fact, so full of thought provoking work that it would be nearly impossible to characterize it as examining simply one entity. Rather, the narrative it weaves reveals the complexities that really underlie the process of self-discovery we all embark on as we grow. Moreover, the show demonstrates that the designations between life stages and identities are not hard and fast, but rather exist in a continuum and the acknowledgement of the fluidity between them helps breed a greater understanding of the diverse human experience.