In Fall 2018, David Getsy curated two exhibition on Kentucky-born artist, Stephen Varble, “Rubbish and Dreams: The Genderqueer Performance Art of Stephen Varble†at the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art in New York, NY, and “Stephen Varble: An Antidote to Nature’s Ruin on this Heavenly Globe, Prints and Video from the Early 1980s†at Institute 193 in Lexington, KY.

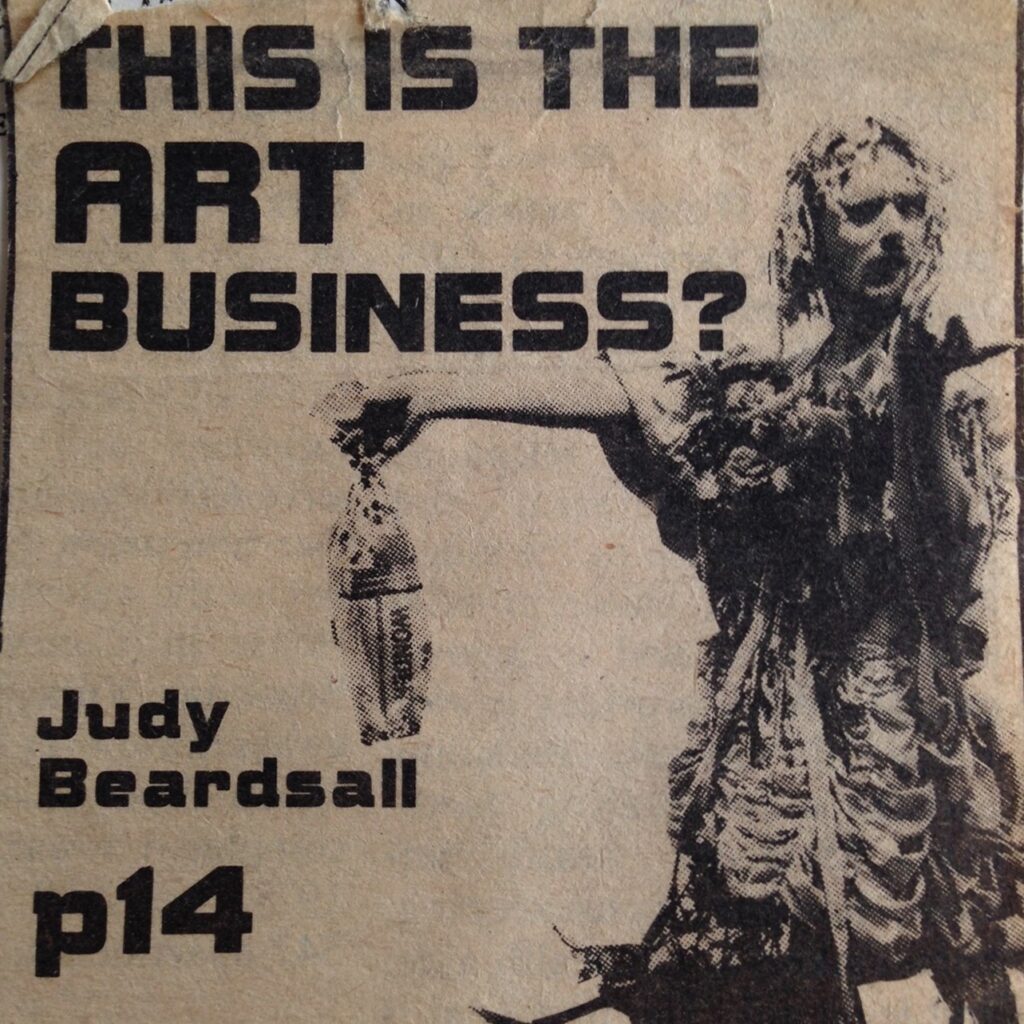

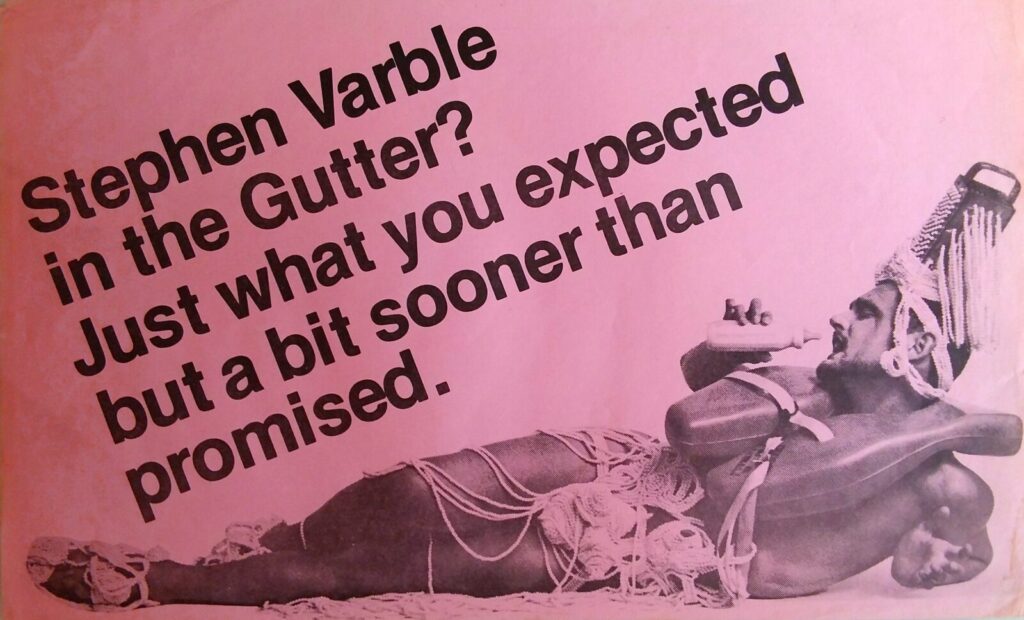

These exhibits offered the first scholarly examinations of this iconic performance artist, who gained notoriety in New York during the 1970s for his irreverent and unauthorized events, staged in galleries, banks, boutiques, public streets, and private apartments. Although his wild performances and elaborate costumes made of debased and discarded materials inspired many of his contemporaries, until now Varble has been written out of history because of his rejection of the art market and its institutions, and also his untimely death from AIDS in 1984 which cut his promising career short.

In this conversation, David Getsy describes the task of researching this under-considered figure and the many Kentuckians who helped him to uncover lost stories, works, and archival documents.

MK: You have spoken about how your research on Stephen Varble was distinct from other projects, as much of it did not take place in libraries and official archives, but rather by sorting through boxes of material in his friend’s attics, porches, and garages. Some key research took place while you were visiting Kentucky last Fall. Could you talk a bit about how that trip impacted your research and some of the insights that you gained by meeting with Varble’sfriends and collaborators and looking through their material?

DG: One of the remarkable things about the work on this project is how generous Varble’sfriends and collaborators have been.  As the project started to take shape (and have an online presence), there were many who reached out to me. In particular, after a lecture I gave on Varble was posted online a couple years ago, I became connected with a few people in Kentucky who were active in Kentucky LGBT history.  Robert Morgan, in particular, has been a great help and a wonderful resource. As well, I got connected with Paul Brown of Institute 193. Both of them directed me to Jean Donohue’s 2013 documentary The Last Gospel of the Pagan Babies.  After watching it I realized I had to continue the research on the ground in Kentucky. Â

This led to many fruitful collaborations, first with the University of Kentucky which brought me to Lexington to give a talk.  It was then that I was able to meet people in person and do some research interviews and archive work in Lexington and Louisville.  At that time, as well, conversations with Paul Brown coalesced into the plan for the current Varble exhibition at Institute 193. As I talked with Kentuckians like Robert Morgan, Charles Rue Woods, and Rebecca Henderson, it became clear to me that Varble’s story couldn’t be told without understanding the complex trans and queer history of Lexington or without the story of the long-established interconnections and movements of people between Kentucky and New York City.

MK: Yes, Lexington’s LGBT art scene is particularly deep, and we are so lucky to have the Faulkner Morgan Archive to do the important work of collecting, preserving, and giving visibility to that history. I wonder if you might describe some particularly salient stories and/or archival objects that you found during your research in Kentucky and elaborate on how you see the interconnections between Kentucky and New York City materialized in Varble’s work. Â

DG: Well, some of Varble’s longest-running friends were those from Kentucky.  He returned to Kentucky throughout the 1970s on regular trips. By taking this seriously, I was able to get a better sense of where his priorities and style came from.  I think the most interesting story for me was of a performance that was done in Lexington on New Year’s Eve in 1974. It was a transitional time for Varble. He had just broken with his partner, Geoffrey Hendricks, and he was struggling to find a new direction without that collaboration.

He made his first costume sculpture that more directly played with gender transformation. He called it his Dream Dress, and it was made of seafoam colored crepe that he had found on the streets of New York.  It was through this dress that he really began to claim the female identity of Marie Debris, and it heralded a period of gender exploration for him. He made it for his triumphal return to Kentucky, and he conceived of the headdress for it at his friend  Rebecca Henderson’s kitchen table in Lexington. She was making Christmas cookie ornaments, and he declared that he could create a wig out of them. He snatched a colander, and they baked cookie-dough curls with it as a skullcap base. He tied twigs and plastic roses to the heavily-crimped dress and wore his cookie curls during the night-long performance at a large near-abandoned house in central Lexington.  He toasted 100 loaves of white Wonder Bread (as a means of toasting in the New Year), with Henderson dancing around to drop honey on the pieces that fell to the ground. It was an intentionally obscure ritual created to mark time and signal the New Year, and it overtook the drafty ground floor of this large house. After the bars had closed, people arrived, thinking it was an afterparty, only to bebefuddled by Varble and Henderson’s choreographed absurdity.

Varble’s performances were often such bewildering provocations, and he was less interested in providing a specific or singular meaning than he was in demonstrating how everyday materials could be transformed into something more mysterious and symbolic — into something greater than themselves.  That’s the core theme of his costumes made out of trash and his inversion of systems of value. There was no documentation of this performance, and I was only able to reconstruct it only after talking with a few people who were at this performance (such as Morgan and Henderson). Not only did the Dream Dress signal the deeper identification as female that would underwrite his later work, the Lexington performance also set the terms for the costumes and actions that would make him notorious when he returned to New York City. Â

MK: Wow, that performance sounds amazing! So that trip to Lexington was really pivotal for Varble. I’m struck by how that story in-and-of-itself inverts the value ascribed to New York by art historical narratives, which so often position it as “the place†that transformative work gets made. It’s also striking how radical that performance must have been in Kentucky in 1974. From your interviews and archival research, did you get a sense of the reception of this work in Kentucky, or how artist here inspired Varble and/or were inspired by him?

DG: Well, like I said, I learned so much from Jean Donohue’s documentary and from talking to Robert Morgan.  Varble was young and in college when he lived in Lexington in the late 1960s, and he was part of a whole queer and genderqueer scene that had coalesced in Lexington.  It was out of the same milieu that the Pagan Babies formed and did their remarkable performances (both live and for the camera). Morgan told me a story about how he would regularly hitchhike to New York City to try and catch John Waters’s Pink Flamingos, which was only screening on the East Coast once a week—at midnight). Â

It was regular for them to think about New York as a place with which they were in dialogue, and like I said there was a network of Kentuckians in New York either visiting or living (like the famous Rollerena!).  So, Lexington already provided a unique base, and I think Varble’s performance was part of a larger set of experimental practices going on in Lexington at the time. It’s my sense that Varble’s attitude toward the use of costume was influenced by his exposure to the queer performance and nightlife scene here, and I don’t think he would have done the same things without that foundation. Â

MK: Do any of his costumes remain, or do you only know about them through photographs?

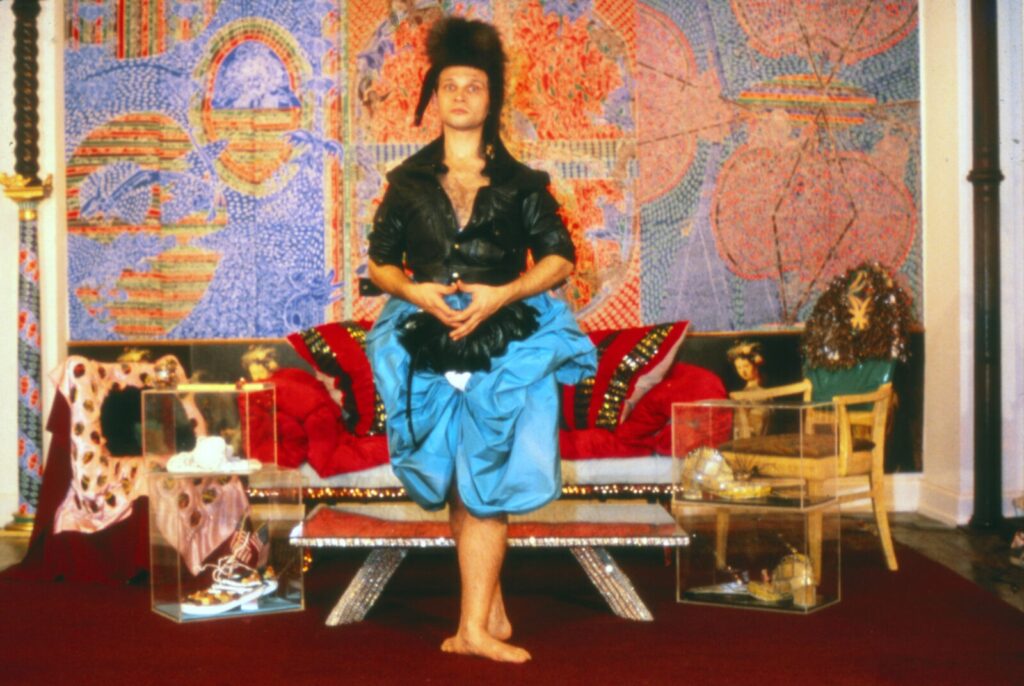

DG: Unfortunately, most everything has been lost or destroyed. Â Sadly, this is the case for many artists who died during the first years of the AIDS crisis. Â As you can see in the video in the exhibition (titled Journey to the Sun), Varble filled his apartment with drawings all over the walls and used his repertoire of costumes for their improvisations and scenes. Â When his partner, Daniel Cahill, passed away a year or so after Varble, everything was put out onto the curb to be taken away as garbage.

There was one costume (the Sky God costume from his 1973 play Silent Prayer) that was destroyed in Hurricane Sandy.  So, none of the costumes survive, save for a few minor fragments.  There is, however, a rich photographic record of Varble’s costumes and performances that, until now, was largely unpublished.  Photographers such as Jimmy DeSana, Peter Hujar, and Greg Day captured Varble’s performances and outfits, and the retrospective exhibition in New York relies on these images alongside video and ephemera.  Journey to the Sun, Varble’s video epic that is being shown in both the Lexington and New York exhibitions, is one of the best records of his many costumes, which he would recombine and adapt regularly.

MK: That really re-affirms what you have said about queer history’s struggle against erasure and how archives serve as a “compromised necessity†that requires an “on-going aggregation of queer attachments.†Given the constraints upon researching Varble, it’s truly impressive how much material you have uncovered and brought to life with these two exhibitions. In terms of the show at Institute 193, I read that the xerographic prints came from Charles Rue Woods. Could you talk a bit about how you came to know Woods, his relationship to Varble, and that part of your research?

DG: It was all through Kentucky connections.  I’d have to look through my notes to remind myself of who introduced me to whom, but when I started investigating Varble’s network, I was able to find friends of his like Henderson, Woods, Ree Wilson, and Susan King — each of whom connected me to other friends and collaborators. Most of the research for the project took the form of multiple oral history interviews, the first of which I did in 2011. I initially connected with Woods over email in early 2017 and then went to interview him at his home in Queens, New York.  Originally from Kentucky and an alum of UK, he moved to New York in 1975 initially to work in theatre and then worked as an editor.

He became connected with Varble through mutual friends from back home. In 1979, he went on tour as a member of the entourage of the Village People. He then returned to New York in the early 1980s and began a lifelong career as a significant designer of book covers for a number of publishing houses. Soon thereafter, Charles became a central member of Varble’s group of collaborators (called “The Happy Arts School of Manuscript Illuminationâ€).  He appears in Journey to the Sun and its prelude Lady Hercules(where he does the opening monologue).  Charles was very close to Varble and his partner Daniel Cahill, and he was a regular participant in the weekly meetings of their group. Â

He was also instrumental in caring for Varble as he struggled with AIDS in his final year. With great foresight, Charles safeguarded video tapes, manuscripts, and a group of precise photocopies that Varble made from drawings intended to be reproduced.  I’m working with Charles to find appropriate archives for these materials. He donated a few things to the Leslie-Lohman Museum for inclusion in the New York exhibition, and he donated a full suite of xerographic prints to the Faulkner Morgan Archive. Without him, so much from these years would have been forgotten.  He’s been so generous with his memories and his energy, and I’ve learned a great deal from him.

MK: What a gift to have met him, and how fortunate for all of us that he preserved those works. It also seems wonderfully fitting that a suite of Varble’s xerographic prints will not only be donated to the Faulkner Morgan Archive, but also that they will be widely distributed through the catalogue that you produced with Institute 193. As you explore in your essay catalogue essay, Varble became increasingly interested in art that could be easily reproduced and broadly circulated in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Could you talk a bit about the role that you see reproducible media, such as photocopies and videotapes, playing in Varble’s aesthetics?

DG: Varble had long pursued the inversion of hierarchies of value. Â He embraced the gutter and transformed trash into glamor. In 1977, he receded from his confrontational relationship with the New York art world because he grew increasingly weary of finding new ways of resisting attempts to co-opt and commodify his spectacular interventions and protests. Â He met Cahill in this year, and he became more uncompromising in his anti-capitalist pronouncements. He began doing private performances in the apartment, the walls of which he filled with drawings and poems. By the late 1970s, he turned to new technologies in a search for way to circumvent the commercial world of galleries and advertising. Â

He started making videos with the aim of producing “video books†that he could distribute widely, and he purchased an early home computer and music synthesizer. His video epic, Journey to the Sun, was the driving reason for these efforts. (At some three and a half hours, it nevertheless remained 70% incomplete at his death in early 1984). In these years, he also embraced the photocopy machine as an artistic tool.  He used it to create collages, and he made drawings with the purpose of reproducing them xerographically. Varble had long used the Xerox machine to make fliers, mail art, and press releases, but he now understood it as a way to make cheap, reproducible works of art.  He labored over the original drawings, and corrected them with Whiteout to make sure they reproduced perfectly.

This is why I call the resulting works “xerographic prints.†They have a level of deliberation and care that is more akin to the printmaker preparing his plate.  As can be seen in the Institute 193 exhibition, they are fully fledged works of art — but they are made through accessible technologies of reproduction so they could be distributed freely and widely. This use of the cheap (but now also precious) photocopy was another way of Varble flipping high and low.  He took the denigrated and elevated it, much like he used rubbish as the material for his awe-inspiring DIY costumes.

MK: The utopian ambitions of Varble’s project and all that he accomplished in his short career is pretty astounding. As a final question, I wonder if you might comment on the traces of Varble’swork that you see in contemporary artistic practice.

DG: When I started showing people this work, so many of them said to me how timely Varble’s practice was.  He embraced the idea of a recombined, non-binary gender for his performance costumes, his work voiced suspicions of commodification and capitalism, and he made DIY dresses out of found, stolen, and recycled objects.  His performances didn’t wait to be authorized by an institution. Instead, he took to the streets to confront new viewers with his disruptions of the business of art and luxury commerce.

All of these things make Varble’s work relevant and revelatory to a new generation of viewers, and I’ve been so encouraged by how young artists, in particular, have looked to Varble’s provocations and seen an attitude similar to their own.  Throughout his short career, Varble vexed the ways in which art and performance had become a matter of commodity exchange, and instead he sought to find a way to make art that did not require art’s conventional pathways and institutions. From his street performances to the delicate xerographic prints and operatic videos, Varble believed that his work could offer an alternative to the debased world of capitalism and exploitations.  He was utopian, irreverent, and sometimes escapist, but he believed that his work could demonstrate to the public that the downcast could be elevated and transformed into the marvelous.

Resources Referenced:

* * *

David J. Getsy is the Goldabelle McComb Finn Distinguished Professor of Art History at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.  His books include Abstract Bodies: Sixties Sculpture in the Expanded Field of Gender (2015), Scott Burton: Collected Writings on Art and Performance (2012), Rodin: Sex and the Making of Modern Sculpture (2010), and, most recently, the collection of artists’ writings, Queer (2016). He is the curator of 2018-2019 retrospective exhibition Rubbish and Dreams: The Genderqueer Performance Art of Stephen Varble for the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art, New York.

Miriam Kienle is an Assistant Professor of Art History at the University of Kentucky. Her current book project examines the artist Ray Johnson’s role as the initiator of the international “mail art†or “correspondence art†movement through the lenses of queer theory, network studies, and the history of interpersonal communication. Her writings have appeared in Media-N, Art Papers, and Artl@s Bulletin, among others. She is also the curator of Pushing the Envelope: Mail Art from the Archives of American Art, on view at the Fleischman Gallery in the Smithsonian American Art Museum until January 4, 2019.