Something Pretty at Transylvania’s Morlan Gallery means to complicate that idea. The artwork does so in a way that is both literal and conceptual, dealing with the viewer’s experience and judgment of the objects on display and the baggage brought to ideas of beauty, aesthetics, identity, and power by the act of looking and the often-trivializing effect of prettiness.

The works shown present an emphatic statement that they are more than nice things to look at. Instead, these works and their artists reach out to the viewer in ways that are deeply affective and lend a great deal of depth and complexity against the often patronizing and dismissive designation of what is called pretty. As Curator Dr. Emily Elizabeth Goodman explains, the word “renders anything associated with the term solely superficial and without any intellectual or cultural significance.†It usually plays on surfaces and appearances, concerned with outward expressions that can be categorized and hierarchized according to things like class, gender, and racial and sexual identity. But Goodman presents a means to complicate this process, a means to challenge the viewer’s own perceptions and biases in regards to art, artists, and their subject matter. It is an opportunity to examine the ways beauty can be a tool of erasure rather than visibility.

Loosely grouped by media, the works are displayed in several sectors within the gallery. Dominating a single walled-off area is a projection of HuiMeng Wang’s video work You Are Beautiful You Should be Seen (2015). As a kind of introduction that immediately grabs attention when entering the gallery space, the video shows the artist on a windy and overcast beach. She washes large exposed driftwood tree trunks and attempts to dig them out even as the blowing sand encroaches and reburies them. A narrator recounts the story that spawned the footage, and explains how such a situation and the beauty it holds is fleeting and often comes up against what one expects it to be. The narration is spoken with a generic male voice and its tone curtly matter-of-fact. As the video loops this disconnect between image and story seems to grate against deeper implications of visibility and beauty. Though a glossy sheen is provided by the narration, Wang’s nuanced meditation on beauty and depiction does not remain hidden.

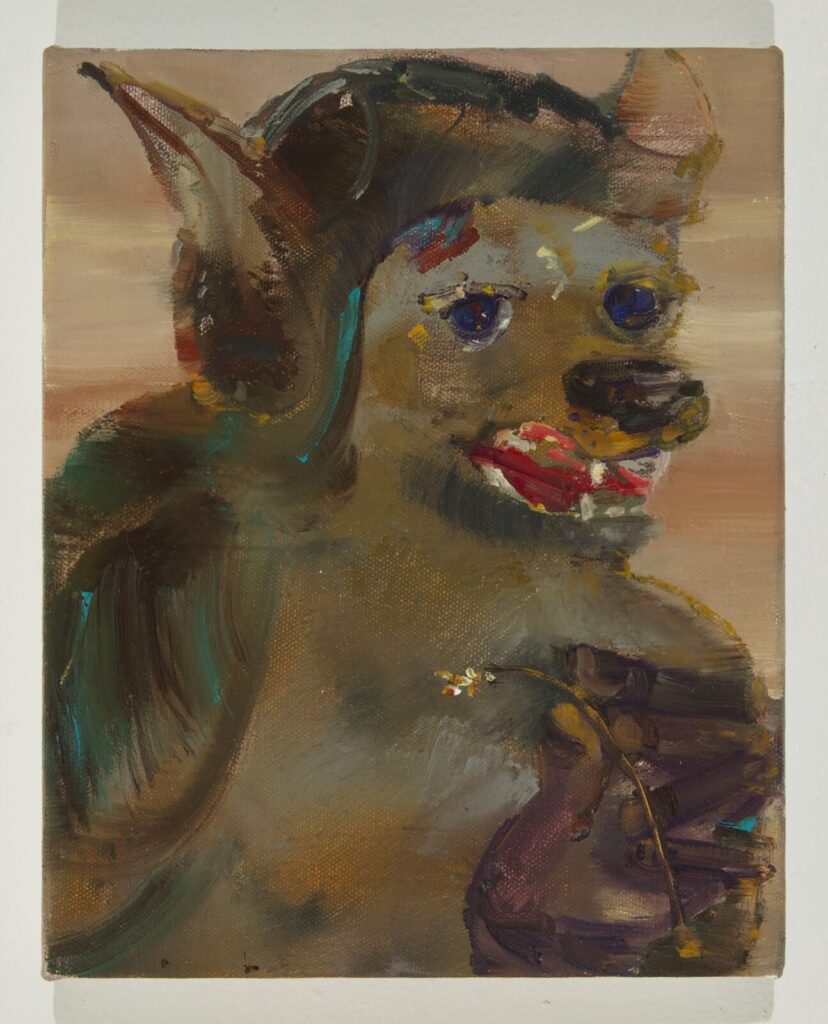

This engagement with pretty surfaces and what lives beneath them (or outside them) is reiterated as the viewer shifts to the exhibition’s sector of painted works. The painted surface was long a modernist preoccupation and here two of the artists artists penetrate the concept of surfaces through an engagement with images and content. Angela Dufresne’s works play with the multifarious conceptions of being painted. It’s Like This (2012) and Listen to Me You Idiot (2013) feature bright and thickly applied swathes of paint combined into grotesque hybrid animal-human faces. But these are not monsters, their expressions are complex and conflicted, and their colors worn like masks. Similar to the idea of being painted up, the concept of expression is both an affectation and a way of staking out and claiming identity. In these paintings, the surface is inextricably tied to both the painted object and painted body. In both cases there is a striking amount of depth.

Likewise are Tiffany Calvert’s painting investigations into the nature of surfaces, application of paint, and complex engagements with the tenuous nature of beauty. Her largest work, Untitled #305 (2018), is a deconstruction of an old Flemish still life. The image is digitally processed and printed on canvas and painted over with bold, wide, and flat strokes of blended color. The painted strokes sit on top of and next to similar digitally produced effects. Together they bring out the constructed nature of the painting, not just in its materials, but in the connection between images and reality. Two other works, Untitled #297 (2017) and Untitled #290, allow the viewer full access to the illusion. Frescos applied to roughly shaped insulation boards, the painted objects only hide their front and back surfaces. The banal material in-between shatters the paintings’ ability to easily inhabit the space of artistic objects and artistic beauty. Instead they teeter on the conceptual edge between art and just pretty objects.

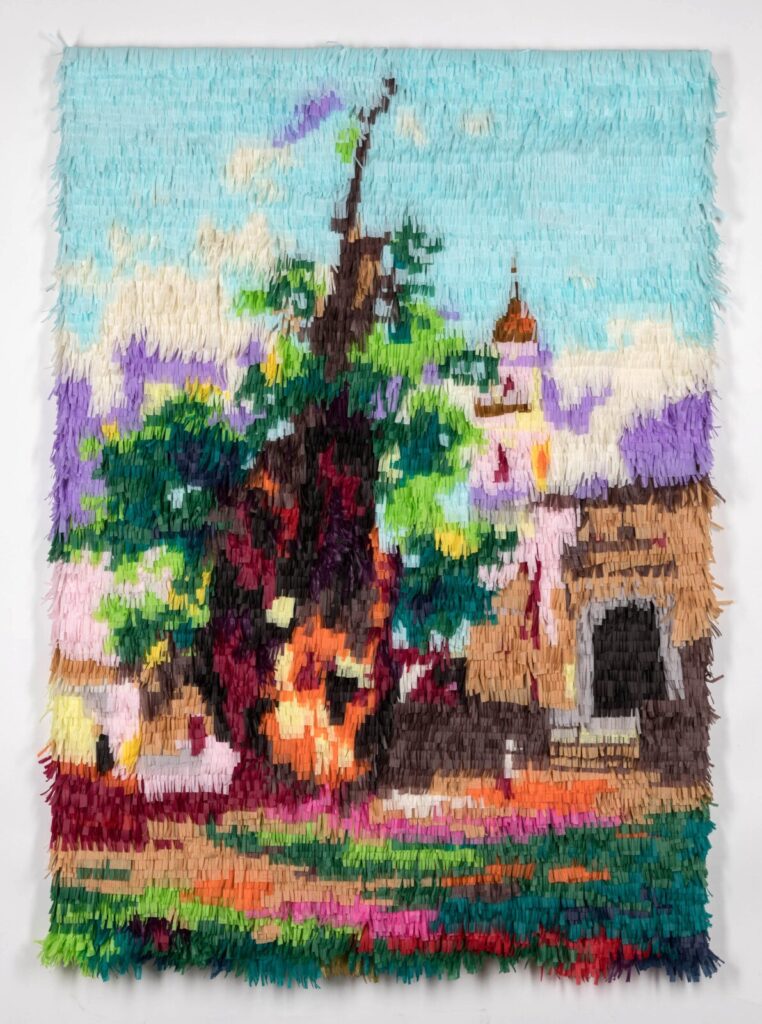

A bridge between materials and beauty is further stressed in the art objects of Justin Favela. Here expectations and identities clash. With images drawn from the oeuvre of 19th century Mexican painter José MarÃa Velasco, Favela’s “paintings†reappraise Velasco’s concepts of land nationalism through the application of media heavy with racial and class implications. Velasco’s lofty nationalist propaganda, in the form of idealized landscapes, is reimagined in Ahuehuete de la Noche Triste (After José MarÃa Velasco) (2017) with the cut paper of the Mexican piñata. The landscapes are abstracted to the point that they lose cohesion and become much more fluid patterns of shape and color. No longer tied to often-overtly racist nationalism, Favela’s objects create new spaces for engagement and exploration where the viewer might be free to encounter identities and experiences with a depth and through materials not before considered.

Subjective ideas of beauty and prettiness are often used to close off certain identities, bodies, or experiences from deeper engagement. The complexity and ambivalence of beauty is a common thread in the overall experience Goodman has curated. All these artworks have a depth that seeks to muddle the pleasurable and powerful implications of looking. This is a call to reexamine what it means to look. This seems most complete in Stephan Rolfe Powell’s glass objects. They begin as playful and aesthetically interesting but reveal much more in the implications of their forms. Two colorful glass objects, Cracking Frenetic Glare (2006) and Twilight Curiosity Buns (2000), are playful, erotic, presented as pseudo-bodily spectacles. Yet below their surfaces runs an anxiety about such bodily comparisons, especially as the objects sprout long phallic tubes from suggestively shaped bulbous forms. They reflect back on the viewer the subjective of the gaze.

This anxiety becomes more acute in Powell’s two large curved plates of glass. These one-inch thick glass walls, beautifully backlit, stand on low pedestals and tower above the heads of most visitors and confront the viewer with complex, patterned forms that dip and flow through the depth of the glass. The complex tangles of colorful tubes seem to inhabit their own world within the glass, locked inside but on the verge of escaping outward. At first pleasing to look at, the forms grow more sinister the more they are considered. What could be flowers or simple geometric shapes might be mouths or other orifices attached to long squirming creatures or phallic organs. Like with Powell’s other works, there is a transformation in the experience of looking as the surface-level beauty deepens into more complicated and even unsettling territory.

In this exhibition, the viewer is confronted and must likewise confront what it means to look at, see, and appraise things and bodies. The power dynamics of expectations versus experience can be reconsidered and rerouted. In the end these works demand more than a passing a glance but a more critical and compassionate look.