​The best way to take in “Pop Stars! Popular Culture and Contemporary Art†at the 21C Museum and Hotel in Lexington, Kentucky, is to make a pilgrimage, the way I did. On a gorgeous Sunday morning, after a beautiful slumber in a plush hotel room, take the elevator to the second floor. When the doors slide open the first thing you see: two fiberglass arms and hands clasped in prayer hanging on a white wall, fingertips spinning a glittery blue basketball. It’s the perfect joke, and yet also the perfect icon.  “Icon†in this instance is literal. Hank Willis Thomas’s “Faith†is a sacred, 3-D representation of multiple urges all pulled together into one succinct object and moment, a Harlem Globetrotters hymn to showmanship, a sad and simple reverie on what it takes to be a star when no one thinks you can be one, outside of that one thing they always think you can do.

There’s a lot of iconography and showing off going on in “Pop Stars!,†currently on display through May 2020. It’s a big and ambitious show that deserves repeat viewings. Fandom gets recalibrated and turned into strategies for resistance and even a little revolt. Everyday idolatry becomes both a vernacular and endpoint in pieces dedicated to what “Pop†constitutes today: a constellation of superstars, from Britney to Kurt to Kim to Barack to Abraham Lincoln, celebrities of every ilk given treatments in oil, silkscreen, video, neon, and so on. This adoration and awe are laced through the obsessions of artists trying to figure out what it all means and what they can do with it. In an era when everyone has easy access to the apparatus of fame-creation via social media, a super-awareness has bloomed inside people’s skulls and manifested on their screens. Continual, virtual fame-hunting, fame-shaming, fame-faming. Fame is courted, everyone priming themselves for it. It’s what life is. A “true self†is now a selfie. So is everyone’s soul, it seems.

​“Pop Stars!†deals with this kind of embarrassment of riches by homing in on all kinds of fames and fortunes and considering both the meaning and meaninglessness of biography, posing, and consummating identity through selling it. R. Luke Dubois’ “(Pop) Icon: Britney†is a video screen ensconced in old-school gold Rococo framing, hidden speakers broadcasting the vocal-fry lullaby known as Brittney’s voice. Britney Spears in the work is a smeared automaton, and yet poignant somehow because of it.  Our love for her makes her go into a kaleidoscope of guises; she is a ghost trying to figure us out, giving us what we want, but then again scaring us because of it. Her beauty is an amalgamation of banality and working-on-all-cylinders star power, a fierce need to please smashed up with exhaustion and confusion and hurt. And Dubois’ treatment, while satirical, is reaching for holiness, grabbing at the hem of her electronic garment, wishing Britney could be more than she is, yet wishing, too, for nothing else but what she is.

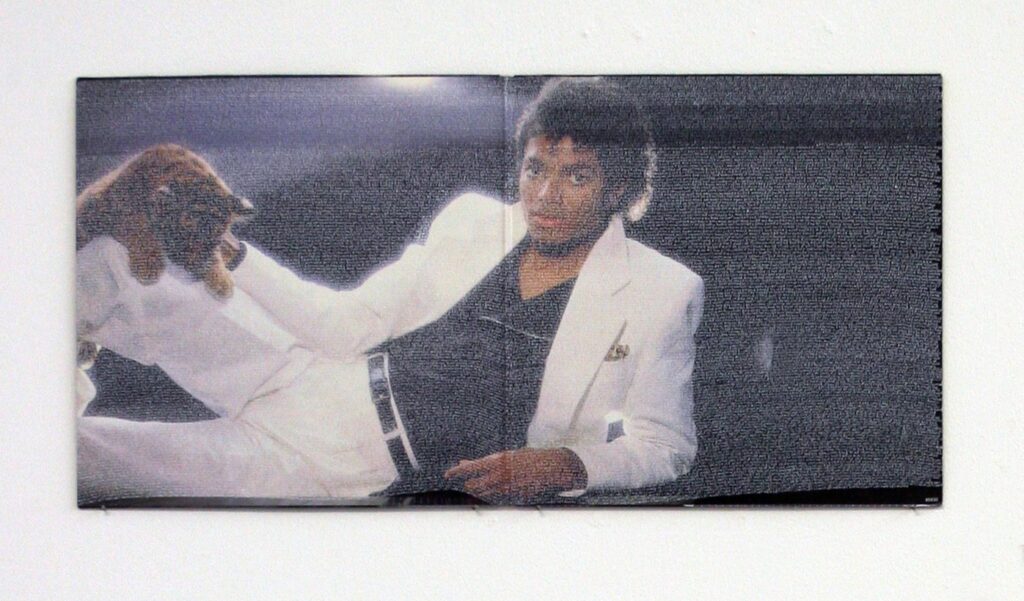

Andy Warhol, the creepy and somehow sweet granddaddy of Pop, its progenitor and mysterious slave, was a devout Catholic. He went to mass obsessively. That spirit of wanting to worship haunts all aspects of this handsome and beautifully arranged exhibit, “Pop†being the driving force,†and “Stars!†being the gasoline that keeps everything moving in fast motion toward oblivion. One of the loveliest works is one of the simplest:  Graham Dolphin’s “36 Michael Jackson Songs,†a paean to fan obsession complicated, of course, by Michael’s tragic history as a fading star offering up Jesus Juice. Dolphin in an extra-tiny, OCD script writes out the lyrics to Jackson’s songs on top of the Thriller album cover. The whole thing has a throwaway finesse to it, a combo of doodles and diary entries and monks creating illuminated manuscripts. Yet the purpose seems to be to figure out a meaning that has somehow collapsed, trying to cipher out the joy of what pop used to bring, what it can’t sustain except through scribbling it on itself.

Warhol did the same kind of thing with silkscreens and Polaroids, hunting down the lost memory of pop-culture innocence by making Liz’s lips a smeary red, by turning the tomato soup he loved as a kid into a totem so ripe and rich it becomes a full-on low-brow/high-brow ringtone. He traced the junk in our lives back to a necessary aesthetic impulse; he found God in Brillo Pads and Coca-Cola.

Rebecca Campbell takes Warhol on with an oil-on-canvas-with-gold-leaf knockout that both eulogizes and diffuses Candy Darling, one of Warhol’s Superstars, in one fell swoop. Titled appropriately enough “Candy Darling,†it’s the Mona Lisa of the show, taking in light and saving it up in its flat yet somehow glorious surface, a painting of a silkscreen of a painting, with a little bit of a nod to Abstract Expressionism as both pun and punishment. Candy Darling’s story gets told without having to tell it, the tragedy of her short life, having died of lymphoma at age 29, revealed through the glamour she craved all her life growing up under the name and gender of James Lawrence Slattery, idolizing Kim Novak and Joan Bennett to the point of wanting to transform lovingly into them. The bleariness of Campbell’s style is reverential and made me go back to the passage in the letter Candy wrote on her deathbed: “Unfortunately before my death I had no desire left for life…  I am just so bored with everything.  You might say bored to death.  Did you know I couldn’t last? I always knew it.  I wish I could meet you all again.â€

Frances Goodman’s “The Sigh,†a hand stitched, sequins-on-linen swoon, gets at that same lush boredom Candy references – it’s a cool blue pixelated pastiche of old-movie sadness turning toward rapture. The materials Goodman deploys here lend the image both pathos and surface sheen, an eroticism that leans toward a good cry. Alexandre Mazza’s video entry, titled “If It’s Meant to Be Love, May It Brand the Soul!†also finds solace in Eros and shininess. It presents an anonymous and beautiful boxer in all his fatigued, sweaty and never unmoving glory. The whole setup is dedicated to endurance and the routine of trying to stay ahead of passing out, building up resistance to forces beyond your control. It also is a good, old-fashioned lovesick poem from a voyeur to the object of desire. Video flesh as shiny as stained glass, muscles bulging, face intent on not being loved, but still absorbing the inevitable adoration of the camera.

Maybe that is what fame is, Mazza’s video seems to be saying: the connection between viewer and the viewed being continually renewed even while thermodynamics take their toll. “Love†and “sex†and “death†become fetishes and flashes, pictographs and posts, obsessions to be lived through and documented. “Pop Stars!†is a great show that revels in fetish and obsession and flash. Curated with humor and respect, using a through-line that narrates the ecstasy and agony of famousness, both craving it and trying to outsmart it, “Pop Stars!†establishes itself within a context and outside of it. “Pop,†whether signified by art or by commerce, has always been about negating history while fixating on it. The show’s curation pulls together a variety of responses to mass culture and to histories of all kinds, what’s popular and what survives being popular, all these depictions of art and life sashaying from ridiculous to profound, with many works blending it all into gorgeous-nonsense/gorgeous-philosophy, until you start asking yourself, “What’s the difference?† At the end of day, when you leave “Pop Stars!†you feel fulfilled, let in on what it means to survive both boredom and elation.  You are captured and then released.