Not quite a group show or even a series of solo shows, works by six artists recently shown at the Lexington Art League were separated out but still strung together by a similar thread. Critic Roland Barthes might have called this connection an umbilical cord, something that does more that just bind things together. Across the galleries the importance of the photographic image resonated through artworks by Lori Larusso, Mark Williams, Christina Conroy, Holly Graham, Josh Dross, and Sarah Madison Brown.

When photographic technology was in its infancy, images were described as being “fixed†to their metal or paper surfaces. Certainly, anyone familiar with the darkroom knows a print needs a chemical fixer to keep it from fading away. Fixing has special connotations to photographs, but it’s a broad definition. Fixing repairs, but it also ties up, sticks on, attaches. In these six exhibitions, there is the strong sense that the objects on display have real weight in the world.

Lori Larusso’s Like sent up the flatness of social media interactions by re-imagining them as large meticulously crafted painted panels. The irony was palpable, even in Larusso’s intentions: can a dearth of images and interactions shared day in and day out be meaningful art? There was a past pop art sensibility to Larusso’s paintings, applied to contemporary forms of expression and communication used by billions. Painted text and images culled from a sea of words and images that swirl through the wastelands of the internet are juxtaposed in ways that focused their aimlessness into sharper points. Why are endless pictures of cats and food so tiresome yet somehow crucial to how we process our emotions? Larusso’s works spoke to this constant flow and what society does to shape it into some kind of shared culture. Experience transformed into something more permanent. Images of cats in sinks, like those represented in Populist Clowd(er) (2019), felt less trivial somehow when carefully rendered and set on white walls.

Of course, art usually deals in monumental feelings. In Mark Williams’ Karst, time is stretched out according to that of geologic forces, but expressed through individual snapshots of experience. These snapshots form the patterned layers that Williams screen prints. The display of Williams’ prints felt both scientific and deeply personal, drawn from the experience of plumbed depths taken in instants. What was gripping about these prints was the way frenetic layers of ink were buoyed by shimmering iridescent paper. A comparison could be drawn between the actions of water and ink that played their parts to create the prints, and the caves from which they were composed. Somewhat ancillary to the prints were several photographs printed on aluminum plates. The reflective surface of Shimmer (2013) lent it a luminous sparkle. Though appearing less abstract than Williams’ screen prints, the cropped rock formations still came across as inarticulate patterns that coalesced the vastness of time into things immediate and emotional.

A similar meeting of science and artistic mythos was Christina Conroy’s Dark Exposure. Like Williams’ Karst, Conroy’s photographs layered together the processes of change to explore the technical strangeness of photographic images. Photographs are often conceits, and these photographs played with peculiar strengths and limitations of the individual image. Here the static image was anything but, and described changes in light and shadow in interesting ways, as in Pathways (2019). Rather than the luminous spheres Conroy created in many of her other photographs, green-lit lines wove through an oddly illuminated wall of trees. The human figures responsible for these moving lights were mostly absent, untraceable in the minutes-long exposure times that reveal Conroy’s method. Time is the photograph’s strength and weaknesses, the human touch able to hide in plain sight in front of and behind the camera.

Holly Graham’s New Life Doll Project was curiously related to Williams’ or Conroy’s looks into time and change. Process and documentation were at the forefront of Graham’s project reclaiming discarded Barbie dolls. They aren’t simply repaired or cleaned but returned a sense of dignity and identity expanded beyond the status of playthings. The images that accompany the dolls, arranged in similarly scientific grids, show before and after shots of heads and bodies. Hair is pruned and restyled, makeup changed or removed, bodies are covered in new hand-sewn clothes, all documented. The process of reclaiming identities and names, “redeeming†them from abuse or neglect, was fascinating, perhaps because of the clinical regularity of the photographs. Emily (2019) is shown before and after, hair straightened and fixed, a mangled left hand cleanly amputated and plastic wrist smoothed and rounded out. Each doll has a name and identity but also a past and any number of potential futures. Only here, these were fixed together to stress the importance of transition and the messiness of concepts like past, present, and future.

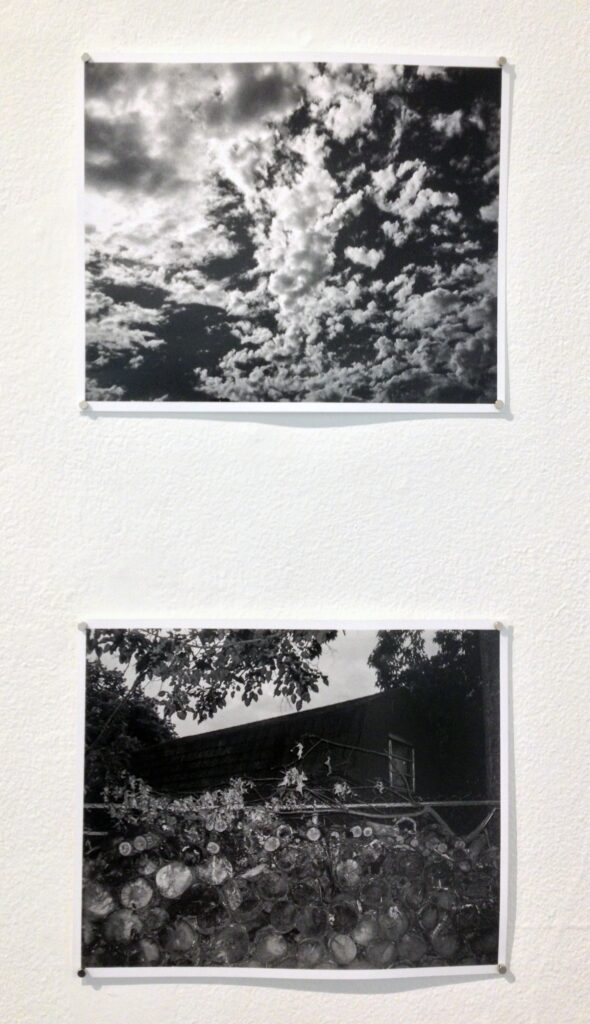

On the Lexington Art League’s second floor, Josh Dross’s I Dreamed in Black in White seemed as straightforward and unadorned as photography could get. The prints themselves were unframed and tacked to the wall, a seemingly haphazard arrangement that ultimately worked to their advantage. Dross’s images speak to transience and uprootedness cast against a timeless rural landscape. Hooked together, many of these images take a hard look at places rarely considered. Several photographs seemed to have been taken from moving vehicles. The blurriness of movement and starkness of their exposures cut against nature’s idyllic imagery. One such photograph, No Sidewalks (2019), is taken in the middle of an empty road that looks backward (or forward) to a concrete overpass overgrown with vegetation. Such a place seems like no place at all, only the transitory nothingness between start and end points. The landscapes are blank and hard to read, or at least they don’t read the way one might want them too.

Like the strangeness of Dross’s places, Sarah Madison Brown’s installation Show Me the Way to Go Home was even more difficult to describe. This final space was wholly transformed; several steps led up through a half closed door that leaked utterly strange lights and sounds. Brown’s chosen title refers to a song by the same name, famously sung in the 1975 film JAWS seconds before the titular shark attacks the boat and crew hunting it. Snatches of sound taken from the movie as well as other unrecognizable bits and pieces from places in South Carolina and California formed a haunting accompaniment to disorienting projections and a garbled litter of printed images affixed to printed wallpaper. The floor was replaced by loose boards, plaster shards, and concrete dust, and the ceiling by looming plastic sheeting illuminated to show pine needles and tar drips. The room was essentially a ruin of splintered images and cut up noise. It was an antecedent nightmare. Accompanying text stated, “Forgetting that nothing lasts forever / Ruins are our guide through a landscape of time.†This spoke for itself.

If images are only expected to represent the things that were, there’s little to be gained. If anything, each of the artists in this LAL exhibition provided a vision of images and photographs as experiences that just happen to be, or have been, taken and hung on the wall. The present of and future of these works is just as crucial, and it seems they aren’t content with being forever fixed in the same space or on the same walls.