Without saying as much, the concepts in Teri Dryden’s exhibition relate to a fairly elusive phenomenon in Japanese aesthetics known as wabi-sabi. Often associated with tea ceremonies (and their utensils) and flower arranging, the concept is concerned with aspects design that seem impermanent or unfixed. The ideas of wabi-sabi can be variously described, but a productive definition, especially for this show of works, might be its concern with the traces of borders between being and non-being, finished and unfinished, beautiful and ugly.

If this seems ambiguous or even cagey, that’s much of the point. To this end, the vagueness concerning the ideas explored in Dryden’s paintings and collages finds a strange cohesion in its conception as a single body of work. This is best reflected in the two walls of small paintings and collages that occupy most of the exhibition’s space. Like its title, rendered without capital letters, the exhibition is an informal gathering of pieces and parts. The haphazard arrangement of these objects can’t be taken as accidental, nor should it. Instead the arrangement can be thought of as an extension of the tensioned elements present in each of Dryden’s collages.

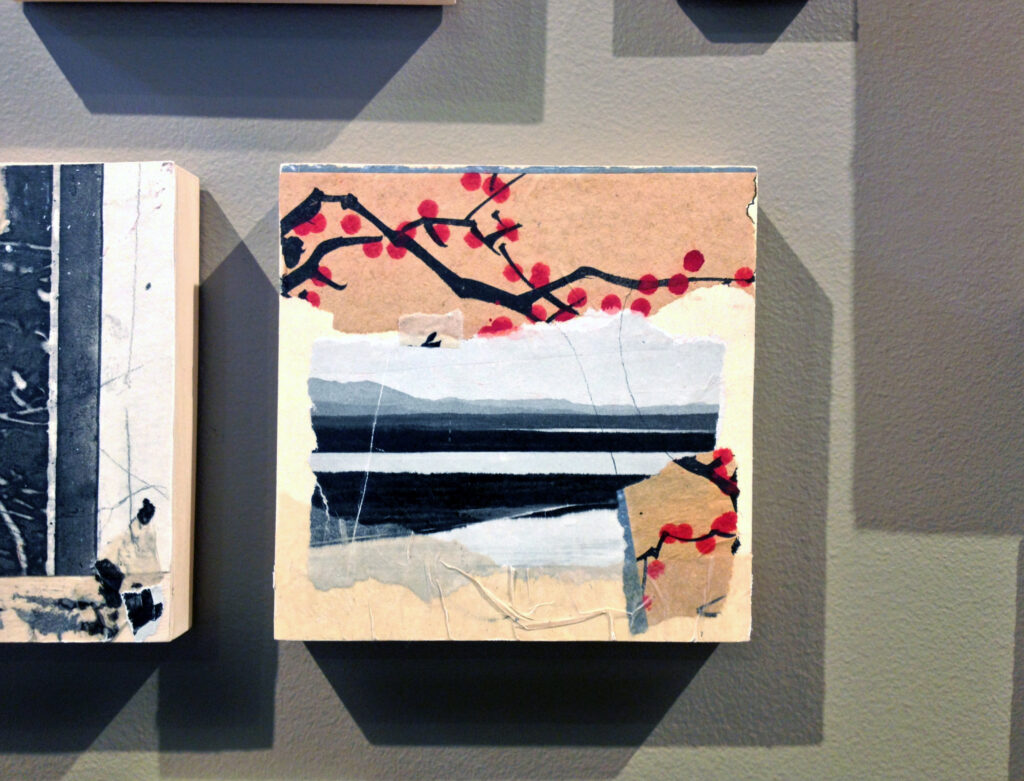

Several pieces find direct and immediate application. One note: except for the few large paintings, no other works are displayed with their titles, a choice that makes the installation more (and purposefully) elusive. So, these “countless†smaller works are free to play with one another in diptych, triptych, and also individually. One vertical triptych includes green and orange patterned cut paper pasted over various other scraps. These squares end up being both abstract arrangements and blocky landscapes. Irregularly cut rectangles function as simple shapes and what appear to be roofed huts or houses. A nearby horizontally oriented set shows an image that is probably a photograph of distant mountains and fields. This is framed by very stylized illustrations of tree branches peppered with red berries. In these combined images (that is, combined from bits of different materials and types of images) the contrast between the pieces creates a somewhat anxious tension between figuration and non-figuration.

The overtness of this collaging of differences provides another layer of interest (no puns here). The fact that the pieces of paper Dryden put together play both as bits of paper and as the elements of new images seems important to the overall project. The conflict of difference plays a large role in what makes these pieces work. Within the works as well as among them, unresolved difference creates a space where the unsettled nature of art works to its benefit rather than detriment.

There’s the small square collage whose layers are comprised of paper crushed and pushed into rippling strata peppered with Japanese text. Another layer of materiality played against smoothness or cohesion. Or there’s instances of text, especially Japanese illegible to an English-speaking audience, transformed into its graphic components of line and shape. Or there are several works with frames made from both infinitesimally thin paper and much thicker wood covered in patterned fragments set next to those whose paper nearly tumbles over the edges. There are even several pieces, like one with a frenetically rendered bird’s nest with eggs, that seems curiously stuck outside the continuum of objects on the walls. This is one of the few overtly figurative pieces, and it hangs apart in its specific uniqueness.

Again, the various tensions between so many differences are what make Dryden’s project compelling. Even the difficulty in discussing the individual pieces gives the exhibition this interest. Without titles, the small works aren’t singled out or placed into the relief of this or that. Again it’s more vague than that. The poles of “this work†versus “that work†give way to a network where even the triptych and diptych groupings are suggestions of context. So within the single work or all the works is a web of playful ambiguity.

To speak more on the microcosm of the individual piece warrants a look at a few unassuming works that can be lost among the entire installation. Some very close and introspective observation reveals a bit more about the ways Dryden’s process of layering incorporates the spectrum of material possibilities. Several such possibilities are on display in a small rectangular work with stone gray paper across one corner, white paint and graphite across its opposite corner, and semi-transparent pieces of paper filling the middle. On these middle pieces, the layered effect is emphasized by pencil diagrams, those below still visible through the pieces of paper placed over them. There is little apparent to their previous purpose: now they only reveal the subtle depth possible when materials are placed on top of each other. The collage of these found fragments gives them new context while those old contexts, still visible, remain playfully suggestive. It’s within these tiny complexes that wabi-sabi appears yet remains playfully obtuse.

To bring things back to the beginning (or perhaps the end as well), the fragmentary nature of Dryden’s works finds itself incorporated into the largeness of the displayed paintings. The effect is obvious, to the point of exaggeration. Three tiny squares climb the wall diagonally towards the edge of a much larger painting titled Begin Again. Inside the painting, along this path, appears a squared of paper fragments, themselves bits of a larger collection of paper and paint layers that spans the entirety of the canvas. Walls and paintings become the same surface. Yet they also retain their distinct differences. Held in a fragile suspension, Dryden’s exploration of materials and things seeks little in the way closure and finality, and this gentle refusal is what ultimately matters.